Colonial Venezuela was a paradox. It appeared marginal, yet it mattered. Its society was hierarchical, yet constantly unsettled.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Venezuela’s colonial history cannot be read as a straight line from conquest to emancipation. It was a fractured journey, marked by the violence of first encounters, the slow accumulation of institutions, the emergence of a plantation economy, and the persistent resistance of those who lived at the margins. For much of the Spanish imperial era, Venezuela seemed peripheral compared with Peru or Mexico. Yet that sense of neglect proved misleading. The same apparent marginality allowed new forms of identity to take shape, culminating in one of the earliest independence declarations in South America. To trace these centuries is to confront a story that feels simultaneously neglected and pivotal.

The Early Settlements (1520s–1560s)

First Encounters and Conquest

When Columbus sighted the Venezuelan coast in 1498, his men were struck by the houses on stilts rising above the waters of Lake Maracaibo. They compared the sight to Venice, and the name “Venezuela” was born.1 The encounter was fleeting, but it hinted at the dense human landscape already present along the coast. For decades afterward, Spanish incursions remained tentative.

The Welser concession of the 1520s illustrates the improvisational nature of Spain’s early colonial strategy. Unable to fund expeditions directly, Charles V farmed out rights to German financiers. The results were disastrous. The German governors pursued gold with brutal disregard for indigenous communities and little concern for sustainable colonization. Their tenure left a bitter memory, an early example of how European rivalries played themselves out on American soil.2

Permanent Settlements

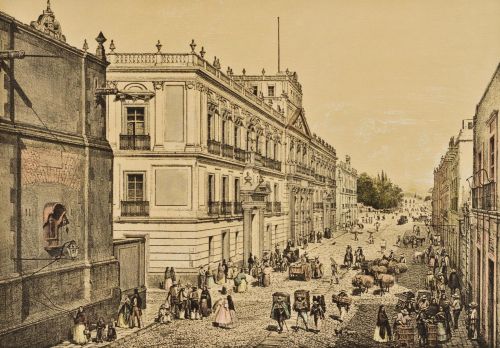

Stability came slowly. Cumaná, founded in 1521, clung precariously to life through repeated indigenous uprisings and rebuilding efforts. Margarita Island, valuable for its pearl fisheries, offered another anchor. Coro was founded in 1527, and it briefly served as the seat of colonial authority. Only with the establishment of Caracas in 1567 did the Spaniards secure a capital that could sustain administration and attract settlers.3 Geography shaped success: the valleys around Caracas provided fertile soils and defensible terrain. What began as precarious footholds eventually hardened into permanence.

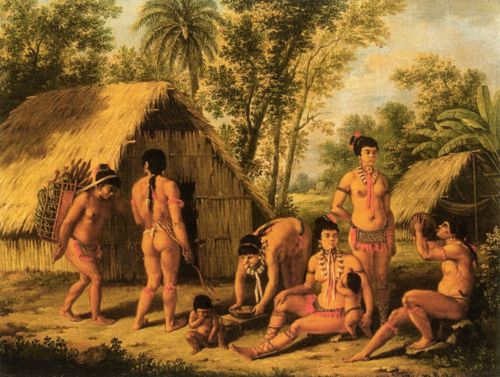

Indigenous Resistance and Accommodation

Yet permanence was never uncontested. The Caribs and Cumanagotos harassed the Spanish relentlessly, leveraging their mastery of local terrain. The Spanish responded with violence, but also with missions, alliances, and the imposition of encomiendas. Epidemics ravaged native populations, weakening resistance but also fracturing communities. Accommodation sometimes followed, but it was not surrender. In the long term, survival often meant retreating into missions or remote zones beyond colonial reach. The memory of resistance never disappeared.

The Colonial Economy and Society (1570s–1700)

The Rise of Cacao

Cacao transformed Venezuela. By the seventeenth century, plantations stretched across the coastal valleys, and European demand fueled the colony’s fortunes. Unlike silver in Mexico or Potosí, cacao was agricultural wealth, dependent on steady labor. That labor first fell upon indigenous peoples, but their numbers plummeted under disease and coercion. By the early seventeenth century, the importation of enslaved Africans became essential.4

The Atlantic slave trade linked Venezuela to the wider imperial economy. Ships carrying enslaved men, women, and children arrived at Puerto Cabello and La Guaira, feeding the expansion of cacao haciendas. Each pod harvested was tied to suffering and coercion. Yet cacao also tied Venezuela into global networks, making this seemingly marginal colony indispensable to sweet-toothed Europeans.

Social Stratification

Colonial society reflected both Spanish ideals and local realities. At the top, peninsulares monopolized official posts, while criollos held economic power through land and slaves. Beneath them, a shifting mosaic of mestizos, mulattoes, and free blacks navigated ambiguous status. Castas created complex hierarchies, with color, origin, and legitimacy woven into a rigid social fabric.5

But reality resisted such tidy order. On the frontier, llaneros mixed Spanish, indigenous, and African elements. In towns, artisans of mixed ancestry carved out autonomy. In villages, enslaved Africans sometimes purchased freedom and reshaped kinship networks. The colonial hierarchy claimed stability, but beneath its surface lay improvisation, contestation, and blurred identities.

The Role of the Church

Religion saturated colonial life. The institutional Church baptized, married, and buried the colony, while orders like the Jesuits and Capuchins pushed into the interior. Missions gathered dispersed peoples into reductions, reorganizing life around Christian ritual and labor discipline.6

The Church was not simply spiritual. It became a major landholder, owning estates and cattle ranches. Its moral authority lent legitimacy to colonial hierarchies, but it also sheltered dissent at times. Confessors listened to the grievances of slaves. Preachers denounced abuses. The Church’s role was thus double: agent of control, but also a space where injustice could be articulated, if rarely resolved.

Integration into the Spanish Empire (1700–1780s)

The Bourbon Reforms

The eighteenth century altered the balance. With the Bourbon dynasty came a determination to tighten imperial control. Venezuela was no longer a neglected frontier. In 1777, the Captaincy General of Venezuela was created, centralizing administration and enhancing the crown’s authority.7 The colony now mattered, and with attention came intrusion.

Taxation increased, trade was regulated more strictly, and local officials faced closer oversight. For criollos accustomed to autonomy, these changes bred resentment. For the crown, they represented rationalization and profit.

Trade Monopolies and the Guipuzcoana Company

The clearest symbol of reform was the Guipuzcoana Company, founded in 1728. Dominated by Basque merchants, it monopolized cacao exports. The Company disciplined production, curbed smuggling, and enriched its shareholders. Yet to local planters, it embodied oppression. Dutch and English smugglers continued to slip into Venezuelan ports, offering better prices and reinforcing resentment of monopoly.8

Economic grievance was never far from political grievance. The revolt of Juan Francisco de León in 1749, directed against the Company, revealed how deeply criollos chafed under Bourbon measures. Though suppressed, the rebellion was a rehearsal for independence: local elites asserting rights against imperial structures.

Frontier and Mission Zones

The Bourbon century was also an age of expansion. In the Llanos, cattle ranching grew, giving rise to the llanero horsemen whose independence would later tilt the balance of war. Along the Orinoco, Jesuit missions sought to stabilize frontiers, creating semi-autonomous enclaves where indigenous peoples lived under a hybrid order. Yet these frontiers remained unstable, vulnerable to raids, flight, and resistance. The map of eighteenth-century Venezuela was patchy, a mosaic of control, negotiation, and contestation.

Resistance and Revolt

Indigenous and African Resistance

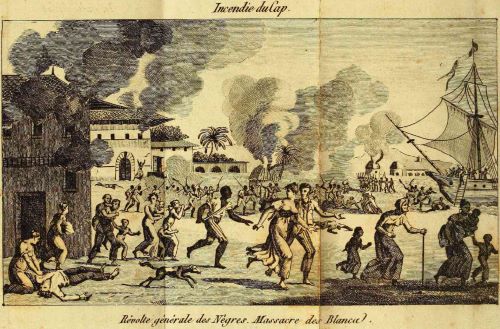

Colonial domination was never total. Caribs resisted into the eighteenth century, using rivers as highways of defiance. Enslaved Africans resisted daily through flight, sabotage, and rebellion. Maroon communities emerged in remote areas, sustaining alternative orders beyond colonial control.9 These acts of defiance rarely toppled the system, but they reminded colonists that power was always precarious.

The 1749 Revolt of Juan Francisco de León

De León’s uprising was born of economic frustration but carried political weight. Criollos rallied against the Guipuzcoana Company, demanding freedom to trade. The revolt failed militarily, but it left a legacy of protest. It showed that elites could mobilize popular support, and that imperial authority could be shaken.10 The echoes of 1749 carried forward into the revolutionary decades to come.

Enlightenment Currents

By the late eighteenth century, the Enlightenment’s vocabulary of rights and sovereignty filtered into Venezuela. Universities taught modern philosophy. Intellectual circles debated liberty and reason. Books circulated despite censorship. For a colony long seen as peripheral, these ideas resonated with particular intensity, offering tools to critique hierarchy and imperial subordination.11

The Road to Independence (1790s–1821)

External Influences

The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were an age of revolution. France, Haiti, and eventually Spain itself convulsed with change. Venezuelan elites watched carefully. The Haitian Revolution terrified slaveholders, even as it inspired visions of liberation. Napoleon’s conquest of Spain shattered the legitimacy of Bourbon rule, creating an opening.

The 1797 Gual and España Conspiracy

In this charged atmosphere, radical conspiracies emerged. The plot of Gual and España in 1797 envisioned racial equality and republican liberty. Though swiftly suppressed, it revealed that revolutionary ideas had sunk roots even in Venezuela. Its memory lingered, feeding the fires of later uprisings.12

1810–1811: Break with Spain

April 19, 1810, marked the turning point. The Caracas cabildo, seizing the opportunity of Spain’s crisis, asserted autonomy. A year later, on July 5, 1811, Venezuela declared independence, the first South American colony to do so. Yet independence was fragile. The First Republic fell quickly, undone by royalist resistance, natural disasters, and internal division. Still, the declaration could not be forgotten. It was a claim to sovereignty that reshaped politics forever.

The Wars of Independence

The wars that followed were brutal, protracted, and divisive. Bolívar, emerging as the most enduring figure, waged campaigns of shifting fortune. Royalist llaneros under Boves unleashed ferocity that nearly crushed the republic. Exile, return, defeat, and renewed struggle marked the path. Victory at Carabobo in 1821 finally secured independence, placing Venezuela within Bolívar’s dream of Gran Colombia.13

Conclusion

Colonial Venezuela was a paradox. It appeared marginal, yet it mattered. Its society was hierarchical, yet constantly unsettled. Its economy flourished on cacao and slavery, yet its people resisted through revolt and rebellion. Out of these contradictions emerged independence, not as a sudden rupture but as the culmination of centuries of tension. The structures of inequality persisted, but so too did the determination to redefine identity. To write the history of Venezuela from the 1520s to 1821 is to chart not a smooth arc but a jagged path, rich in struggle, resilience, and transformation.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Germán Carrera Damas, Historia de la historiografía venezolana (Caracas: Monte Ávila, 1961), 21.

- Guillermo Morón, A History of Venezuela (New York: Roy, 1965), 33–35.

- John V. Lombardi, Venezuela: The Search for Order, the Dream of Progress (New York: Oxford University Press, 1982), 14.

- Federico Brito Figueroa, La estructura económica de Venezuela colonial (Caracas: Universidad Central de Venezuela, 1966), 58–60.

- Inés Quintero, La sociedad colonial venezolana (Caracas: Alfa, 2006), 91–94.

- Carrera Damas, Historia de Venezuela, 110.

- Allan J. Kuethe and Kenneth J. Andrien, The Spanish Atlantic World in the Eighteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 157–59.

- Brito Figueroa, La estructura económica, 202–203.

- Quintero, La sociedad colonial, 128.

- Lombardi, The Search for Order, 41–44.

- Morón, A History of Venezuela, 197.

- Carrera Damas, Historia de Venezuela, 272.

- Lombardi, The Search for Order, 77–80.

Bibliography

- Brito Figueroa, Federico. La estructura económica de Venezuela colonial. Caracas: Universidad Central de Venezuela, 1965.

- Carrera Damas, Germán. Historia de la historiografía venezolana. Caracas: Monte Ávila, 1961.

- Kuethe, Allan J., and Kenneth J. Andrien. The Spanish Atlantic World in the Eighteenth Century: War and the Bourbon Reforms, 1713–1796. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Lombardi, John V. Venezuela: The Search for Order, the Dream of Progress. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

- Morón, Guillermo. A History of Venezuela. New York: Roy, 1965.

- Quintero, Inés. La sociedad colonial venezolana. Caracas: Alfa, 2006.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.11.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.