Communism has been one of the most influential economic theories of all times; recognizing its influence is key to understanding both past and current events.

The Rise

Overview

Communism has been one of the most influential economic theories of all times; recognizing its influence is key to understanding both past and current events. Moreover, the competition between communism and capitalism as played out in the Cold War was arguably the defining struggle of the 20th century. This section provides a brief overview of communist ideology in the European and Russian contexts and includes information on the rise of the Soviet Union under Vladimir Lenin and its continuation under Joseph Stalin. It concludes with an explanation of the tensions that surfaced at the end of World War II between the United States and the U.S.S.R. that led to the Cold War.

What is Communism?

Communism is a political ideology and type of government in which the state owns the major resources in a society, including property, means of production, education, agriculture and transportation. Basically, communism proposes a society in which everyone shares the benefits of labor equally, and eliminates the class system through redistribution of on income.

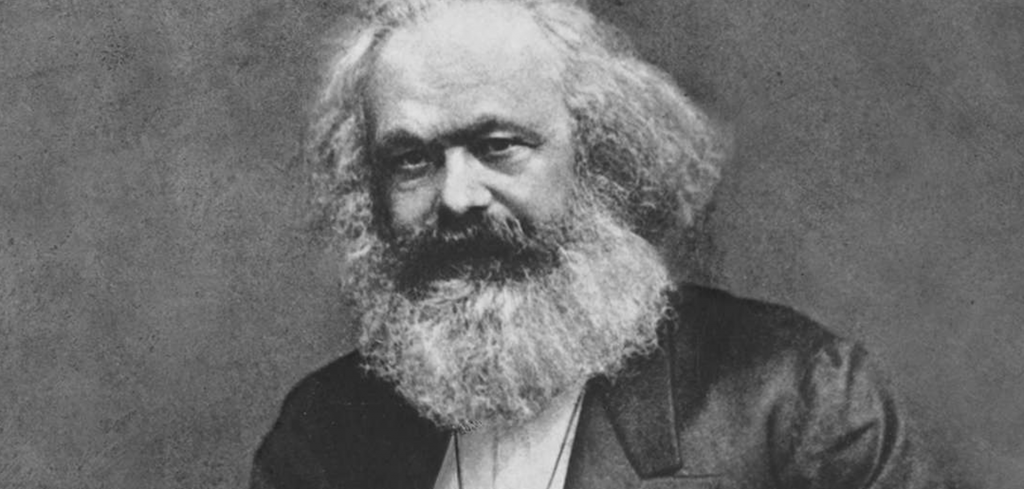

The Father of Communism, Karl Marx, a German philosopher and economist, proposed this new ideology in his Communist Manifesto, which he wrote with Friedrich Engels in 1848. The manifesto emphasized the importance of class struggle in every historical society, and the dangerous instability capitalism created. Though it did outline some basic requirements for a communist society, the manifesto was largely analytical of historical events that led to its necessity and suggested the system’s ultimate goals, but did not concretely provide instructions for setting up a communist government. Though Marx died well before a government tested his theories, his writings, in conjunction with a rising disgruntled working class across Europe, did immediately influence revolutionary industrial workers throughout Europe who created an international labor movement.

Civil Unrest: Communism, Workers, and the Industrial Revolution

As envisioned by Marx, Communism was to be a global movement, inspiring and expediting inevitable working-class revolutions throughout the capitalist world. Though the book had not yet been published, these revolutions had already started in early 1848 in France. The new urban working class that lived and worked in terrible conditions throughout Europe got fed up with their life of squalor as they saw upper-class citizens (the bourgeois as Marx labeled them in the Manifesto) living lives of luxury. The ideas and goals of communism appealed strongly to the revolutionaries even after the 1848 revolutions collapsed. For the next several decades, fed-up lower class workers and peasants held tight to the legacy of the 1848 revolutionaries and communist ideology waiting for the right moment to capitalize.

The Russian Context: The Russian Revolution

Communism was adopted in Russia after the Russian Revolution, a series of revolutions that lasted throughout 1917. For centuries leading up to World War I, Russia was ruled by an absolute monarchy under which the lower classes had long suffered in poverty. This tension was exacerbated by the nationwide famine and loss of human lives as a result of World War I. The first revolution began when the Russian army was sent in to control a protest led by factory workers who had recently lost their jobs. However, the army did not follow the Czar’s orders and many soldiers defected and protested in solidarity with the workers. The military quickly lost control of the situation, and the Czar was forced to abdicate. The Imperial Parliament formed a provisional government, but Vladimir Lenin’s Bolshevik party overthrew it in October 1917. Bolshevik leaders appointed themselves to many high offices and started implementing communist practices based on Marx’s ideology.

When the Czar was dethroned, Vladimir Lenin returned to Russia after being exiled for anti-Czar plots. Other revolutionaries including Leon Trotsky also returned to Russia to seize the opportunity. The two established the Bolshevik party, a communist party that was staunchly opposed to the War, which continued to wreak havoc on the unstable nation. The Bolshevik’s anti-war platform was popular among the Russian people, and Lenin used this momentum to overthrow the provisional government, take control of the country and pull Russia out of the war. Lenin also promised “Bread, Land and Peace” to the large populations affected by the famine, further increasing the party’s popularity. However, when the Bolsheviks gained only 25 percent of votes in the 1917 elections, Lenin overturned the results and used military force to prevent democratic assembly. He established several state-centered government programs and policies that would continue, in some form, throughout the reign of the Soviet Union. His plan for national economic recovery, the GOLERO Plan was the first of this type and was designed to stimulate the economy by brining electricity to the whole of Russia. Lenin established a national free healthcare system and free public education. He also established the Cheka, a secret police force to defend the success of the Russian Revolution and censor and control anti-Bolshevik newspapers and activists. Following two failed assassination attempts, Lenin, following a suggestion from a military leader named Joseph Stalin, authorized the start of the Red Terror, an execution order of former government officials under the Czar and Provisional Government, as well as the royal family.

Shortly thereafter, the country dissolved into civil war between the ruling Bolsheviks and the White Guard, a loose alliance of anti-Bolshevik parties including tsarists, right-wing parties, nationalists and anti-communist left-wing parties. Both sides engaged in terror tactics against each other included mass executions and the establishment of Prisoner of War labor camps, and wreaked havoc on the country’s already-weak agricultural and economic system. Following the end of the war in 1921, Lenin established the New Economic Policy, which allowed for private businesses and a market economy, despite its direct contradiction with Marxist ideology. He also annexed Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan to provide geographic and political protection from the Party’s political and ideological enemies. He died in January 1924 of a heart attack. After his death, several members of the Communist Party’s executive committee, the Politburo, vied for control of the government.

The Rise of Joseph Stalin

Joseph Stalin, born Ioseb Besarionis Dze Jugashvili (in his native Georgian), was a key military leader throughout the Red Terror and the Civil War. As you learned, Stalin actually proposed the idea of fighting the Communist Party’s enemies through systematic mass terror and killings to Lenin. As General Secretary under Lenin, he also oversaw brutal military actions throughout the civil war and led the 1921 invasion of Georgia to overthrow an unfriendly social-democratic government. In Georgia, Stalin took the lead in establishing a Bolshevik regime in the country hard-line policies that forcefully repressed any communist opposition. Lenin disagreed with Stalin’s tactics in Georgia, and right before his death dictated notes in his Testament warning of Stalin’s excessive ambition and obsession with power, and advised that he be removed from the General Secretary position. However, Lenin died shortly thereafter and Stalin allied himself with several other Politburo members to suppress Lenin’s Testament and remain in a position of power.

Over the next few years, Stalin isolated his major opponents in the Communist Party, eventually throwing them out, and became the unchallenged leader of the Soviet Union. He officially ruled the country from 1924-1953. In his early years as leader, Stalin revamped the Soviet Union’s economic policy, replacing Lenin’s New Economy Policy with a highly centralized command economy controlled by the state, which rapidly industrialized the country. However, the quick transition from agriculture to industry disrupted food supply and caused a massive famine lasting from 1932 to 1933. Simultaneously, people deemed to be political enemies began being imprisoned in labor camps or deported to remote areas of Russia. In 1934, actions against political enemies, including members of the Communist Party who disagreed with Stalin’s policies, intensified with the start of the Great Purge. About one million people were executed from 1934 to 1940 under Stalin’s orders.

In 1939, Stalin signed a Non-Aggression Pact with Nazi Germany’s Adolf Hitler. However, when Hitler broke the pact and invaded in 1941, the Soviet Union joined the western Allies in their battle against the Nazis. With the United States other allied European countries leading the charge on the Western Front and Stalin pushing back from the East, the Nazis were defeated with the Soviet Red Army’s capture of Berlin in May, and the western armies’ D-Day invasion in June 1945.

The End of World War II and the Division of Europeo

Overview

Despite their wartime alliance, tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States and Great Britain intensified rapidly as the war came to a close and the leaders discussed what to do with Germany. Post-war negotiations took place at two conferences in 1945, one before the official end of the war, and one after. These conferences set the stage for the beginning of the Cold War and of a divided Europe.

The Yalta Conference

In February 1945, when they were confident of an Allied victory, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Stalin met near Yalta, Crimea, to discuss the reorganization of post-WWII Europe. Each country’s leader had his own set of ideas for rebuilding and re-establishing order in the war-torn continent. Roosevelt wanted Soviet participation in the newly formed United Nations and immediate support from the Soviets in fighting the ongoing war in the Pacific against Japan. Churchill argued for free and fair elections leading to democratic regimes in Central and Eastern Europe, especially Poland. Stalin, on the other hand, wanted Soviet “sphere of influence” in Central and Eastern Europe, starting with Poland, in order to provide the Soviet Union with a geopolitical buffer zone between it and the western capitalist world. Clearly there were some key conflicting interests that needed to be addressed.

After much negotiation, the following outcomes of the Yalta Conference emerged:

- Unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany, the division of Germany and Berlin into four occupational zones controlled by the United States, Great Britain, France and the Soviet Union.

- Germans, civilians and prisoners of wars, would be punished for the war (reparations) partially through forced labor to repair the damage they caused to their country and to others.

- Poland was reorganized under the communist Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland, and Stalin promised to allow free elections there (but failed to ever follow through on it).

- The Soviet Union agreed to participate in the United Nations with a guaranteed position as a permanent member of the Security Council.

- Stalin agreed to enter the Pacific War against Japan three months after the defeat of Germany.

- t

The Potsdam Conference

Soon after the conference it became clear that Stalin had no intension of holding up his end of negotiations. He eventually allowed for elections in Poland, but not before sending in Soviet troops to eliminate any and all opposition to the communist party in control of the provisional government. The 1947 “elections” solidified communist rule in Poland and its place as one of the first Soviet satellite states.

A second conference was held from July 17 to August 2, 1945, in Potsdam, Germany. Roosevelt had died in April, so his successor, President Harry Truman, represented the United States. Churchill returned to represent Great Britain, but his government was defeated midway through the conference and newly elected Prime Minister Clement Attlee took over. Stalin returned as well. Stalin’s actions in Poland, and other parts of Eastern Europe were well known by this time, and it was clear that he was not to be trusted to hold his end of the bargain. In light of this, the new representatives from the United States and Great Britain were much more careful with their negotiations with Stalin. Truman in particular believed Roosevelt had been too trusting of Stalin, and became extremely suspicious of Soviet actions and Stalin’s true intensions. The final agreements at Potsdam concerned:

- The decentralization, demilitarization, denazification and democratization of Germany

- The division of Germany and Berlin, and Austria and Vienna into the four occupations zones outlined at Yalta

- Prosecution of Nazi war criminals

- Return of all Nazi annexations to their pre-war borders

- Shifting Germany’s eastern border west to reduce its size, and expulsion of German populations living outside this new border in Czechoslovakia, Poland and Hungary

- Transformation Germany’s pre-war heavy-industry economy (which had been extremely important for the Nazi military build-up) into a combination of agriculture and light domestic industry

- Recognition of the Soviet-controlled Polish government

- Announcement of the Potsdam Declaration by Truman, Churchill and Chinese leader Chiang Kai-sheck outlining the terms of surrender for Japan: to surrender or face “prompt and utter destruction”

Annexation: Soviet Socialist Republics

As per its Yalta agreement, the Soviet Union was set to invade Japan on August 15. While the Potsdam declaration did not specifically mention the newly developed atomic bomb, Truman had mentioned a new powerful weapon to Stalin during the conference. The timing of the bombings, on August 6 and 9 suggest that Truman preferred to keep the Soviet Union out of the Pacific War and out of post-war dealings with Japan. Moreover, this show of nuclear prowess on the part of the United States was also a warning to the Soviet Union, and effectively ended either side’s desire to continue working together, and marked the start of the nuclear arms race that underscored geopolitical considerations of both the United States and the Soviet Union throughout the Cold War.

The Soviets annexed their first territories in eastern Poland on September 17, 1939, under the terms of the Non-Aggression Pact made with Nazi Germany. Soon after, the Red Army went to war with Finland in order to secure a buffer zone of protection for Leningrad (St. Petersburg). When the war was over, Finland ceded the territories demanded by the Soviets plus Karelia. The Soviet Union subsequently annexed the Baltic States, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, as well as Moldova in 1940. Several other territories (modern-day Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan and Armenia) had been annexed prior to 1939.

In addition to the Republics, several countries in Eastern Europe operated as Soviet satellite states. These countries were not officially part of the USSR, but their governments were loyal Stalinists, and therefore looked to and aligned themselves with the Soviet Union politically and militarily via the Warsaw Pact.

A Divided Germany

After the Potsdam conference, Germany was divided into four occupied zones: Great Britain in the northwest, France in the southwest, the United States in the south and the Soviet Union in the east. Berlin, the capital city situated in Soviet territory, was also divided into four occupied zones. Germany also lost territory east of the Oder and Neisse rivers, which fell under Polish control. About 15 million ethnic Germans living in this territory were forced to leave, suffering terrible conditions during their expulsion. Many froze or starved to death on over-crowded trains, while others were subject to forced labor camps under Polish and Czechoslovakian governments.

West Germany, or the Federal Republic of Germany, was officially established in May 1949. East Germany, or the German Democratic Republic, was established in October 1949. Under their occupying governments, the two Germanys followed very different paths. West Germany was allied with the U.S., the U.K. and France and became a western capitalist country with a market economy. In contrast, East Germany was allied by the Soviet Union and fell under highly centralized communist rule. More information about the socioeconomic paths of the two Germanys, as well as those of Western and Eastern European countries can be found in later sections.

The Cold War

Overview

The foundations of the Cold War were, as seen in the previous section, well established by the close of WWII. This section explains the roots of the Cold War, its consequences in Europe and globally, and the major political players involved. As many in the United States and Western Europe feared, the Iron Curtain did descend upon Europe, further dividing a continent already brutally devastated by war.

A “cold” war, as opposed to a “hot” war, is one that does not involve direct military confrontation. Instead, a cold war plays out through competing economic systems, military alliances as well as arms building and the accumulation of other resources, and sometimes through proxy or surrogate wars. In this section, learn more about how the West and East confronted each other throughout the Cold War.

Movement was one of the main differences between the East and the West during the Cold War. While the Western NATO allies were beginning to form what we now know as the European Union (which is fundamentally based on four freedoms all involving movement: the free movement of people, goods, services, and capital), people living behind the Iron Curtain were restricted in their day-to-day life. The place where these competing systems were in direct juxtaposition was the Berlin Wall, the dividing point between East and West- with freedom mere meters away.

The Long Telegram

Throughout WWII the U.S. position was to remain friendly to the Soviet Union, as it was an extremely important ally against the Nazis. Soon after the war ended, the wartime alliance completely disintegrated. George Kennan served as Deputy Chief of Mission of the United States to the USSR from 1944 to 1946. In March 1946, he sent his famous “Long Telegram,” which outlined his critiques of the Soviet system and highlighted several concerns he had regarding the future of the two countries’ relationship.

Essentially, Kennan concluded that the Soviet Union, and its brand of communism, was at war with capitalism and any country that subscribed to its ideology. Kennan warned that the Soviet Union believed that there could be no peaceful co-existence between the communist and capitalist world.

Kennan and the Long Telegram influenced the Truman Doctrine and served as the foundation for American Cold War policy and containment theory.

The Truman Doctrine

On March 12, 1947, President Truman spoke before congress and asked for $400 million in aid to Turkey and Greece. This address became known as the Truman Doctrine and was the first manifestation of containment theory as part of U.S. foreign policy toward the Soviet Union. The American government was worried Greece’s suffering economy would lead to support of the already-growing communist National Liberation Front. Additionally, they were wary of the Turkish government’s plan to enter into negotiations with the Soviet Union over control of the Dardanelle Straits, which divided Europe and Asia.

Truman feared that without U.S. economic support, these two regions would fall to communism, and to de facto Soviet control, which could lead to communism spreading throughout the Middle East and southern Asia, dramatically increasing Soviet power in the world. (This theory of countries falling one after the other to communism became known as the Domino Theory.)

Truman’s request was granted and became the foundation for U.S. Cold War foreign policy. Throughout the Cold War the United States’ top priority was to “contain” the spread communism in the world. Early on, this meant economic aid to countries vulnerable to communist and socialist rhetoric as seen in Turkey and Greece. Later, it meant war, as the United States engaged in Korea and Vietnam to defend non-communist governments from communist invasion and takeover.

The Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was a metaphor for the extreme political and ideological division that separated Western Europe from the Soviet Union and its satellite states in the east. While there was physically no structure marking this divide, the Soviet Union worked extremely hard to ensure that Western democratic and capitalist influence did not infiltrate its borders.

The Marshall Plan vs. Comecon

The Marshall Plan (or the European Recovery Program) was a direct consequence of Containment policy. It was an economic and social reconstruction plan for Europe designed to speed up recovery in the countries still suffering the effects of WWII. The plan is named after Secretary of State George Marshall, who presented the theory behind the plan in a commencement address at Harvard in 1947. He believed that economic stability was key to political stability, and crushing Soviet influence, in Europe.

Once talks began to put the plan in place, all of the Allies, including the Soviet Union, in an effort to gain Stalin’s trust, were invited to a meeting in Paris to negotiate the terms of American aid in Europe. Unsurprisingly, Stalin was extremely skeptical of the plan and believed it would create an anti-Soviet bloc. Though the aid was open to all European countries, Stalin ordered those under his Eastern Bloc to reject American aid, and created a Soviet plan as a response to the Marshall Plan.

In 1948, President Truman asked Congress to pass the Economic Cooperation Act establishing the Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA) to facilitate implementation of the Marshall Plan in 16 western European countries. Aid under the Marshall Plan first went to Greece and Turkey to continue to crush communist influence there. Under the plan, money was transferred to each European government. An American advisor from the ECA, and local government, business and labor representatives oversaw the implementation of funds. Money from the Marshall Plan was mostly used to buy American imports like food and fuel, as local sources had been wiped out by the war. Once basic needs were stable, the money was used to physically reconstruct infrastructure and industries.

In total, the Marshall Plan supplied Europe with more than $12 billion from 1948-1951, divided based on population and industrial power. The United Kingdom received the most ($3 billion), followed by France ($2 billion) and West Germany ($1.5 billion).

Between 1948 and 1952 European industrial production increased by 35 percent and agricultural exceeded pre-war production levels. Standards of living increased dramatically. Experts disagree on how much credit is due to the Marshall Plan; however, they largely agree that it sped up recovery, and was certainly instrumental in reducing political discontent and stemming the communist tide in Western Europe.

The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (founded in 1949 by the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Poland, Romania, Czechoslovakia and Hungary) was Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc reaction to the Marshall Plan and Organization for European Economic Cooperation in Western Europe.

Since Marshall Plan aid was extended to all countries in Europe, including those aligned with the Soviet Union, Stalin was worried that his communist allies would be pulled into strong economic relations with the West and created his own economic assistance plan to keep them in line.

In the beginning of negotiations, the plan was for COMECON to be a forum for coordination of national economic plans through unanimous ratification of any changes or new policies. However a year later, Stalin increased the authority of COMECON in directly intervening in member states, especially in areas of foreign trade.

NATO vs. The Warsaw Pact

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the Warsaw Pact were the military alliance equivalents to the Organization for European Economic Cooperation and COMECON in their respective blocs.

NATO was founded in April 1949 by 10 Western European nations, and the United States and Canada. It is an intergovernmental military organization based on a system of mutual and collective defense. This cooperation is guaranteed by Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty, which states that an armed attack against one member is to be considered an attack against all members. However this article was not invoked until well after the Cold War, following the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks on the United States.

According to the first Secretary General Lord Hastings Ismay, the aim of NATO was “to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down,” and emphasized the importance of trans-Atlantic relations between the U.S. and Europe.

The outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 served as NATO’s first true test of military cooperation. Before the war, the organization was mostly a political alliance; however once the war broke out, it was forced to organize a formal military structure and strategy. Members formed the Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) as the command center, selected Dwight D. Eisenhower as SHAPE Commander, and began military exercises in 1952.

In order to maintain peace on the European continent, the Soviet Union suggested it join NATO but the proposal was flatly rejected as members questioned the Soviet’s true motives. Soon after, NATO made West Germany a member in order to have access to manpower and territory right at the Soviet border. In response, the Soviet Union, along with seven other Eastern European countries founded the Warsaw Pact with the aim of protecting their countries from NATO’s “threat to the national security of the peaceable states.” The Warsaw Pact reaffirmed “the establishment of a system of European collective security based on the participation of all European states irrespective of the social and political systems….” Similar to NATO’s charter, the Warsaw Pact included an article on mutual and collective defense in the event of an attack on a member state.

During the Cold War, the two organizations never engaged in direct combat with each other on the European continent. However, they did meet each other on the global stage, fighting strategically and militarily to contain each other’s influence.

Dark red: Soviet Union Red: Soviet satellite states Light red: other Soviet allies Yellow: China and its allies

Dark blue: U.S.A. Blue: other NATO members Light Blue: other U.S. allies

The Berlin Wall

Despite being divided like the rest of Germany, the actual city of Berlin sat well behind East Germany’s border. Until 1952, crossing between East and West Germany was relatively simple. However, the leader of East Germany and Stalin became increasingly suspicious of Westerners crossing into the East, and a barbed wire fence was erected on the East/West German border.

The borders between East and West Berlin, however, remained physically undivided, and getting to West Berlin became the easiest way to escape to West Germany. By 1961, when the Berlin Wall was constructed, 3.5 million East Germans, mostly young and well educated, had left.

In order halt this mass emigration from East Germany, East German State Council chairman, Walter Ulbricht, and Soviet Union leader, Nikita Khrushchev, discussed the possibility of building a wall. On August 12, 1961, Ulbricht signed an order to officially close the border and build a wall.

Checkpoint Charlie

Checkpoint Charlie (Friedrichstrasse) was the best-known west-to-east crossing on the Berlin wall. It was the only crossing open to non-Germans and Allied military forces. The checkpoint was the site of a U.S.-Soviet standoff during the 1961 Berlin Crisis, when Soviet officials stopped a U.S. diplomat from entering East Berlin. Five days later, U.S. and Soviet tanks were lined up and facing each other on either side of the checkpoint. The standoff was peacefully resolved the next day.

As the most visible and famous checkpoint, it was often featured in films depicting the Cold War Era, and remains a popular tourist attraction for those visiting Berlin.

Restriction of Movement: Goods, Services, and People

Once the wall was erected, emigration from East Germany became much more difficult. Many families were split and became unable to visit each other. The wall also prevented Western goods from entering East Berlin; for example, East Germany developed its own version of Coca Cola, Vita Cola, to keep western influence out. The wall also slowed down the flow of information from West Germany to East Germany; however, people continued to smuggle newspapers in from the West, and East Germans could still listen to radio broadcasts from Western stations like the BBC and Radio Free Europe (however, this was illegal and East Germans could be punished if they were found out).

The Fall: Solidarity and Other Political Movements of 1989

Poland

Solidarity was the first independent labor movement in a Soviet bloc country. It was founded in 1980 in Poland in the shipyards of Gdansk. Since 1970, Polish workers had been protesting and striking due to rising food prices that became increasingly unaffordable under their worker’s salary. In 1980, the Polish Communist government announced a raise in meat prices, causing another round of strikes that summer, which culminated in the formation of Solidarity in August, led by Lech Walesa. Solidarity members and the government confronted and negotiated with each other for a year until the General Wojciech Jaruzelski, first secretary of the Polish Communist party, ordered a massive military putdown of the strikes, and had the movement’s leaders arrested.

Solidarity remained an underground movement until 1989, when it was invited to participate in roundtable talks with the Polish government to quiet growing unrest. The three outcomes the parties agreed on meant big changes for the Polish government and its citizens. The Round Table Agreement legalized independent trade unions, created the office of the Presidency (abolishing the power of the general secretary of the Communist Party), and established a Senate. Solidarity became an officially recognized political party and challenged the Communist party in the fully free 1989 Senate elections, winning 99 percent of the seats. This election was a clear blow to Communist Party power in Poland, but the Soviet Union, and the rest of the Warsaw Pact, under Gorbachev’s reforms was no longer in a position to militarily defend its satellite states. Solidarity leader Walesa was elected President of the Republic of Poland in 1990. After the success and influence of the early ‘90s, Solidarity resumed activities as a traditional trade union.

Czechoslovakia

Political change and movement away from the Communist system was taking place in other Soviet satellite states as the Soviet Union was clearly on the decline. The Berlin Wall fell in November 1989 signaling the end of Soviet influence in East Germany. That same month, Czechoslovakia experienced their “Velvet Revolution,” a series of non-violent protests and countrywide strikes organized by the Civic Forum that led to the overthrow of the Communist party in December. Leader of the Civic Forum, Vaclav Havel, became president after free and fair elections were held in 1990.

Hungary

Hungary had been undergoing liberalizing changes since the 1960s when leader Janos Kadar began releasing political prisoners, increasing workers’ rights, and introducing market system aspects to Hungary’s economy. In 1988, Kadar was replaced by Communist hardliner Karoly Grosz, splitting the Hungarian Communist Party, which eventually liberalized and reorganized itself as the social democratic Hungarian Socialist Party in 1989. In May 1989, Hungary opened its borders with Austria, being the first Eastern bloc country to break through the Iron Curtain; thousands of East Germans fled west through this open border during the Pan-European Picnic held in August. Hungary held its first free and fair elections, and withdrew from the Warsaw Pact in 1990.

Bulgaria

Bulgaria also experienced a relatively peaceful transition from communism. Several opposition parties began emerging in the late 1980s. Communist leader Todor Zhivkov tried to avoid making concessions to these parties who demanded religious and human rights; however, the opposition gained too much support from the West for the faltering communist system to put them down. After Zhivkov was overthrown and replaced by Prime Minister Petar Mladenov, Bulgarian citizens took to the streets to protest the continuation of communist rule and demand democracy and free elections. With the backing of the Bulgarian people, the opposition groups formed the Union of Democratic Forces in order to strengthen their voice. The Communist government realized it was at a loss and stepped down on January 15, 1990.

Romania

In contrast to these peaceful transitions, the Romanian Revolution of 1989 was extremely violent, involving several bloody public uprisings, and culminating in the execution of former dictator Nicolae Ceausescu and his wife. The National Salvation Front led by Ion Iliescu (a former Communist party leader) took control, and Iliescu was elected head of state in 1990.

Yugoslavia

The fall of communism in the late 1980s presented an unprecedented opportunity for rewriting the social contract in many of the former communist countries. In the case of Yugoslavia’s republics, with the exception of Slovenia, there was no congruity between the identity of the nation-state and the population that lived in it. The population was multiethnic and, although tensions never ceased to exist during communism, interethnic conflicts was kept under check by the Yugoslav Communist Party and its repressive apparatus. With Tito long gone and with the rapidly changing international environment in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the ethnic tensions in Yugoslavia blew open.

Originally published by the Center for European Studies: A Jean Monnet Center of Excellence, to the public domain via U.S. Department of Education Funding with the University of North Carolina.