Pregnancy evolved from a feared consequence of sin to a celebrated pillar of civic virtue — but always with tightly drawn boundaries.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Pregnancy in early America was a multifaceted experience situated at the crossroads of Enlightenment science, Christian morality, domestic ideology, and civic nationalism. Between the colonial period and the Jacksonian era, views of reproduction shifted dramatically — from Puritan fears of original sin in the womb to republican ideals of motherhood as a duty to the emerging nation. As women’s reproductive lives became more medicalized, surveilled, and politicized, pregnancy was increasingly seen not merely as a private matter but as a cornerstone of national identity. This essay explores the evolving discourse and lived realities of pregnancy in early America through four lenses: medical theory and practice, religious belief and moral judgment, domestic and legal expectations, and pregnancy as a symbol of republican motherhood.

Pregnancy and Medical Practice in Early America

Medical understanding of pregnancy in 18th-century America was heavily influenced by British and continental European traditions, particularly Galenic and humoral theories. The body was seen as a system of fluids in delicate balance, and pregnancy was understood as a shift in that equilibrium. Women were believed to be naturally colder and wetter, their reproductive organs requiring special regulation through diet, bloodletting, and emotional control.¹ Medical advice often emphasized moderation in eating and sexual activity, avoidance of strong emotions, and prayer as a stabilizing force for the “weaker sex.”²

Throughout the 1700s, childbirth and prenatal care remained primarily the domain of midwives — typically older women with experiential, not formal, training. Midwives offered a holistic approach that combined herbal remedies, spiritual guidance, and hands-on knowledge of labor.³ However, by the early 19th century, male physicians began to assert authority over pregnancy, increasingly characterizing it as a pathological condition requiring scientific oversight. This shift was part of a broader professionalization of medicine and a marginalization of women’s traditional knowledge.

The rise of lying-in hospitals in urban areas such as Philadelphia and New York marked a transition in how pregnancy was managed. Hospitals were often advertised as sites of charity and modern hygiene, yet they were also spaces of social control, where poor or unwed women were monitored and sometimes subjected to experimental practices.⁴ Medical men began writing pregnancy guides aimed at middle- and upper-class women, emphasizing the need to follow physician advice and presenting pregnancy as a fragile and risky state best handled by trained professionals.

Despite this growing medical authority, most American women still gave birth at home, surrounded by female kin and midwives. Pregnancy remained both intimate and communal — a shared experience passed down orally through generations. This blend of medicalization and tradition produced a complex culture of care and caution, where science and folklore coexisted uneasily in the gestating body.

Religion, Morality, and Reproductive Sin

In colonial New England, Puritan theology cast a long shadow over reproductive experience. Pregnancy was understood through the lens of original sin — the result of fallen flesh rather than divine grace. Even wanted pregnancies carried echoes of Eve’s curse: “in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children.”⁵ Women were taught to approach pregnancy with piety, penitence, and submission, seeing it as both a punishment and a spiritual trial. Miscarriage and stillbirth were often interpreted as signs of divine disfavor or personal moral failing.

This theological framework shaped not only private devotion but also public ritual. Pregnant women often underwent periods of seclusion, spiritual introspection, and preparation for death.⁶ Given the real risks of childbirth in a pre-antiseptic world, it was common to write a “death speech” or final letter to one’s children. Ministers preached sermons likening labor to the passion of Christ, and pregnant women were exhorted to model Christian suffering in the hope of a safe delivery and eternal salvation.

However, the 18th century also saw the rise of more moderate Protestant denominations, like Methodists and Baptists, whose views of pregnancy softened. These sects emphasized grace over judgment and offered a more comforting vision of maternal suffering.⁷ In their view, childbirth could be redemptive, a symbol of God’s providence and the natural order rather than solely a burden of sin. This theological evolution paralleled Enlightenment ideals about the nobility of motherhood and the role of women in civil society.

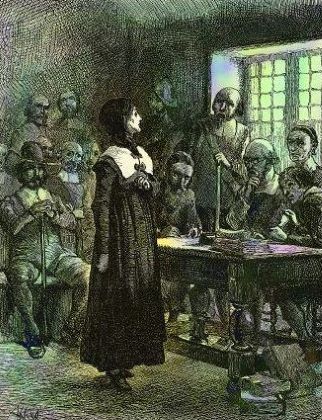

Nonetheless, moral judgment remained particularly harsh for women who became pregnant out of wedlock. Bastardy laws and public shaming rituals — such as fines, church censure, and community scorn — reinforced a rigid moral order.⁸ Female sexuality, when detached from the institution of marriage, continued to be policed with force, even as theological interpretations of pregnancy grew more compassionate.

Legal Structures and Domestic Ideals

In both law and practice, pregnancy in early America was legally framed by patriarchy and property. Under English common law — which heavily influenced colonial legal codes — a woman’s legal identity was subsumed under that of her husband.⁹ This doctrine of coverture meant that married women could not own property, sue, or be sued in their own names. Pregnancy was treated as part of a woman’s marital duty, and any child born within wedlock was presumed legitimate and the legal heir of the husband, regardless of circumstance.

Unwed mothers, however, faced far greater scrutiny. Colonial laws often required pregnant single women to name the father of their child, and bastardy examinations could be invasive and humiliating. Midwives were sometimes enlisted as de facto legal witnesses, reporting on signs of pregnancy, labor, and even the physical appearance of the newborn.¹⁰ The purpose was not justice for the mother, but assurance of financial responsibility from the father or punishment for sexual transgression.

Even within marriage, the law gave husbands considerable control over women’s reproductive lives. A man could demand sexual access to his wife, and while there were cases of divorce on grounds of infertility, a woman’s refusal to bear children was rarely recognized as legitimate.¹¹ Female reproductive labor was considered a natural extension of her domestic role, part of what republican writers later called the “cult of true womanhood” — purity, piety, submissiveness, and domesticity.¹² Pregnancy was not just expected; it was morally and socially required.

These legal and domestic frameworks worked hand-in-hand to create a reproductive regime that celebrated motherhood while restricting female agency. Women were honored as mothers only within the right conditions — married, fertile, obedient — and even then, their rights were secondary to the needs of family, husband, and state.

Republican Motherhood and National Identity

The American Revolution and the early Republic ushered in new ideals that reshaped the meaning of pregnancy. Out of Enlightenment thinking and post-revolutionary fervor emerged the doctrine of Republican Motherhood — the idea that women’s primary political role was to bear and raise virtuous sons who would safeguard the Republic.¹³ This ideology elevated the moral and symbolic value of pregnancy but also deepened its burdens.

Republican Motherhood cast women as moral educators, guardians of virtue, and silent partners in the civic experiment. It required women to be literate, religious, and committed to republican ideals — a far cry from the earlier Puritan notion of women as morally suspect.¹⁴ Pregnancy now signified not just biological continuation but the transmission of national values. It turned the household into a political space and the womb into a patriotic vessel.

Yet this elevation was double-edged. It idealized the maternal body while still denying women full citizenship. They could not vote, hold office, or participate in formal politics. Their contribution was generational — powerful but confined. The image of the noble mother, draped in domestic virtue, became a cultural ideal, enshrined in literature, schoolbooks, and sermons.¹⁵ But it also obscured real pain: miscarriages, death in childbirth, the emotional toll of high fertility expectations.

As America moved toward the Jacksonian era, these ideals began to fracture. The rise of women’s reform movements, especially around abolition and temperance, challenged the idea that a woman’s role ended at the cradle.¹⁶ Yet even then, pregnancy remained the most potent symbol of her social function. The early Republic, born of revolution, had no trouble turning the pregnant woman into a metaphor for liberty — as long as she stayed home and raised the next generation.

Conclusion: Bearing the Nation

Pregnancy in early America was never merely a physical event. It was a site of theological reflection, medical intervention, legal scrutiny, and national aspiration. Across the long 18th century and into the early 19th, pregnancy evolved from a feared consequence of sin to a celebrated pillar of civic virtue — but always with tightly drawn boundaries. Whether feared or praised, the pregnant body was rarely left to its own devices. It was observed, interpreted, and burdened with meanings far beyond the biological.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Wendy Perkins, Midwives and Medicine in Colonial America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 47–48.

- Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785–1812 (New York: Vintage Books, 1990), 65.

- Ibid., 92.

- Susan Klepp, Revolutionary Conceptions: Women, Fertility, and Family Limitation in America, 1760–1820 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 117.

- Genesis 3:16 (King James Version).

- Elaine Forman Crane, Ebb Tide in New England: Women, Seaports, and Social Change, 1630–1800 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1998), 151–52.

- Catherine A. Brekus, Strangers and Pilgrims: Female Preaching in America, 1740–1845 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 102.

- Cornelia Dayton, Women Before the Bar: Gender, Law, and Society in Connecticut, 1639–1789 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 194.

- Marylynn Salmon, Women and the Law of Property in Early America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), 23.

- Ulrich, A Midwife’s Tale, 211.

- Dayton, Women Before the Bar, 172.

- Barbara Welter, “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820–1860,” American Quarterly 18, no. 2 (1966): 151–74.

- Linda Kerber, Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980), 283.

- Ibid., 290.

- Jane E. Dabel, A Respectable Woman: The Public Roles of African American Women in 19th-Century New York (New York: NYU Press, 2008), 37.

- Lori D. Ginzberg, Women and the Work of Benevolence: Morality, Politics, and Class in the 19th-Century United States (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 52–54.

Bibliography

- Brekus, Catherine A. Strangers and Pilgrims: Female Preaching in America, 1740–1845. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

- Crane, Elaine Forman. Ebb Tide in New England: Women, Seaports, and Social Change, 1630–1800. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1998.

- Dabel, Jane E. A Respectable Woman: The Public Roles of African American Women in 19th-Century New York. New York: NYU Press, 2008.

- Dayton, Cornelia Hughes. Women Before the Bar: Gender, Law, and Society in Connecticut, 1639–1789. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

- Ginzberg, Lori D. Women and the Work of Benevolence: Morality, Politics, and Class in the 19th-Century United States. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990.

- Genesis 3:16, King James Version.

- Kerber, Linda. Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980.

- Klepp, Susan. Revolutionary Conceptions: Women, Fertility, and Family Limitation in America, 1760–1820. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

- Salmon, Marylynn. Women and the Law of Property in Early America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986.

- Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher. A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard, Based on Her Diary, 1785–1812. New York: Vintage Books, 1990.

- Welter, Barbara. “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820–1860.” American Quarterly 18, no. 2 (1966): 151–174.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.09.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.