Roman religion was not independent of society.

By Dr. Michael Lipka

Professor of Religious Studies

University of Patras

Introduction

So far, I have analyzed the Roman pantheon as a self-contained, artificial system of concepts. But these concepts were the product of humans, and humans are social beings. It is at this point that Roman society comes into play. It is important to remember here that Roman society or societal groups, or any society for that matter, selects only a very limited number of concepts as constituent of its value system and as embodying societal raison. Those foci not selected are automatically labeled as nonsensical or ‘foreign’ in societal terms. For instance, according to conventional Roman selection it was ‘unreasonable’ for women to vote, to be invested with political power, or to go to war. This does not mean that the Romans could not theoretically conceive of the position of women in these ways, but societal pressure would prevent such a choice of alternative concepts from being put into practice.

Roman religion was not independent of society. John Scheid has aptly remarked: “There was in fact no such thing as ‘Roman Religion’, only a series of Roman religions, as many Roman religions as there were social groups.”1 Defining social groups, however, is not always an easy task, especially in the Roman society of the imperial period, in which freedmen might overrule consuls and slaves turn into patricians, if backed by imperial support. Furthermore, a religious performant, though belonging to a specific social group in the broad sense, might conceptualize divine concepts differently according to the social sub-group in which he acted. These sub-groups were determined, for instance, by age, sex, descent, place of residence, profession, etc.2 Therefore, our categories have to be necessarily broad, acknowledging social differences but allowing for exceptions.

I divide the material into three parts: In the first section, I will deal with the Roman élite, first with the senatorial and then the equestrian order, and finally with the emperor. The second part will turn to the rest of Roman society. The third part is devoted to the role of women in conceptualizing Roman gods.

The Elite

We begin with the senatorial order in the early Republic. It is important to note that this group was the least inclined to any form of negotiation of power in an attempt to defend the status quo of its own privileges against those who had less power or none. This group, then, was unremittingly on the defensive against the other societal groups with regard to the preservation of existing divine concepts and their conceptual foci. Transformations of divine concepts were likely to be promoted from its side only as a result of competition among its own ranks.

Many patrician gentes controlled some or all conceptual foci of a specific cult on a private level.3 Festus, relying on Labeo Antistius, differentiates between public rites open to all Roman citizens and family rituals restricted to specific families.4 Sacrifices of the gens Claudia5 and gens Fabia6 are on record. The latter are attested as providing personnel foci of the cult of Faunus in the case of the luperci Fabiani, alongside the luperci Quinctiales, representatives of the Quinctii.7 The personnel foci of the cult of Hercules at the Ara Maxima until 312 B.C. were members of the Potitii and Pinarii.8 A famous altar from Bovillae was dedicated by members of the gens Iulia to Vediovis Pater in the second century B.C., and the same gens may possibly have usurped a number of cultic foci of the cult of Venus even before Caesar, though evidence is rather scarce.9 The latter case should alert us to the possibility that powerful gentes might project their alliance with a specific god on to the distant past for merely political reasons.

The family alliance with a specific god served social integration. One may remember that the gentes were not only linked to traditional deities, but also kept alive other, very specific family customs. For instance, the gens Servilia venerated a bronze coin.10 Until Sulla, the dead of the gens Cornelia were not incinerated (as was normal among the Roman élite), but were buried unburned.11 The Claudii, Aemilii, Iulii and Cornelii had their own ‘holidays’.12

The disappearance of family cults in Rome in the middle and late Republic appears to have been due to the successful struggle of a part (not necessarily only the plebeian part) of the aristocracy against any form of power monopoly among their ranks, whether in the hands of an individual or of a specific societal group such as the gens. The evidence for this conflict is scarce, but Appius Claudius Caecus, who initiated the transfer of the cult of Hercules at the Ara Maxima from the custody of the gens Potitia and gens Pinaria to the state in 312 B.C., may have been one of its protagonists13 Likewise, the identification of Quirinus with Romulus, presumably dating to the second and first centuries B.C., may result from the same struggle.14 It is conceivable that the “renaming” of the god was initiated, apart from the priests of the god such as his flamen and the Salii Collini, by one or more gentes that had previously privileged Quirinus (Fabii) or Romulus (Memmii?) and grasped the opportunity to act, after Quirinus’ gradual decline in the face of the ascent of Mars.15

Apart from specifically patrician family cults there may have been also plebeian cults. One may refer to the Lares Hostilii and the goddess Hostilina, both undoubtedly connected with the Hostilii, a plebeian gens (at least in the historical period).16 The god Caeculus is clearly linked to the plebeian Caecilii.17 A number of public spatial foci, especially that of the Aventine triad, may go back to plebeian families, and the same may be true of certain ritual foci, most notably that of the ludi plebei.18

On an official plane, the initial monopoly of patrician families in controlling all important foci of public cults was broken by the Licinio- Sextian reforms of ca. 367 B.C., which guaranteed plebeian and patrician families equal access to the decemvirate, as well as by the Lex Ogulnia of ca. 300 B.C., which admitted plebeians into the two priestly colleges of pontiffs and augurs.19 Only a few personnel foci, most notably the major flaminates (see below), remained the exclusive domain of the patricians for the whole duration of the Republican period. Eventually, this distinction became obsolete with the lex Cassia (46/45), which entitled the ruler to confer patrician status on plebeian families.

The most significant personnel foci of the official cults, the flaminates, remained strictly divided between patricians and plebeians in the Republic. Thus, the three major flaminates (of Iuppiter, Mars and Quirinus) were reserved for patricians and the minor flaminates for plebeians.20 A most important point is that at an early stage, the patrician families showed a particular interest in certain (but not all) official cults. This predilection is all the more remarkable, in that the installation of the flaminate presumably predates the political emancipation of plebeian families. In other words, nothing would have prevented the patricians from claiming the later plebeian flaminates as well.

Not only the three major flaminates, but also the rex sacrorum, the two colleges of Salii (Palatini/Collini) and possibly (at least in the early Republic) the vestals were exclusively recruited from patrician families.21 Two of the four institutions were closely connected to the Roman kings, the rex sacrorum, as he continued priestly duties of the king, and the vestals as former custodians of the royal hearth or as attached to the royal household in some other way.

However, it must be strongly emphasized that the monopoly of the most important priesthoods in the hands of the Republican élite in no way meant that its members always used to act in compliance with official cults. At most, this may be said with certainty of the senators (whose religious conduct was monitored by the censors). A warning not to generalize is provided by the Bacchan movement of 186 B.C.: its leaders and followers may have been aristocrats or at least belonged to the socially privileged.22 The actual participation of the higher strata of Roman society would well explain the extraordinary attention the senate paid to the Bacchanalian affair.

In practice, during the whole period of the Middle and Late Roman Republic, the four major priesthoods (pontificate, augurate, decemvirate/quindecimvirate, epulones) were distributed among members of the Roman aristocracy who had already held important magistracies—or were prospective candidates.23 As a rule, these priests never assumed more than a single priesthood, though some exceptions occur as a result of the Hannibalic wars, and perhaps earlier, although the evidence is scarce.24 It was from the time of Caesar (who became both augur and pontifex, later pontifex maximus) and especially under the Empire with the precedent of the emperor himself (who was conventionally a member of all four major priesthoods), that the senatorial élite again began to accumulate official sacerdotal offices of all kinds.25

Despite the ban on the cumulation of sacerdotal offices by an individual, the distribution of priesthoods among the Republican aristocracy was far from even: three patrician families (Cornelii, Postumii, Valerii) supplied two thirds of all known flamines maiores. Of these, the Cornelii provided more than half of all known Jovian flamines.26 While the major flaminates may have remained in the hands of a particular gens for successive generations, such a precedent cannot be asserted of the major Republican priesthoods in general.27 In 104 B.C., a lex Domitia ruled that no more than one member of a specific gens be admitted to each college at a time. Though rescinded by Sulla, this law was re-enacted in 63 B.C. (again, clearly reflecting a system of checks and balances among the ruling élite).28

Under the Republic, the major priesthoods were filled by men of the senatorial order. The two certain exceptions of ‘new men’, Marius and Cicero (who both became augurs), prove beyond doubt the social exclusivity of these four major sacerdotal offices. It was only under Caesar and his successors that this situation changed. From this point on, official priesthoods in general became an instrument at the hands of the emperor, to show his favour towards individuals or entire families.29 There are clear indications that under the Empire, pontiffs and, to a lesser degree, augurs were co-opted from a relatively restricted circle of the senatorial élite, often in virtue of their political allegiance to the imperial family.30 An analysis of the lists of the arvals appointed under the Julio-Claudians has shown that, under Augustus, almost all major senatorial families sent one, and only one representative. It also suggests that, for most of the Julio-Claudian period, sacerdotal seats were largely passed on from one generation to the next among these families (though on occasion among different family branches). This situation changed under Nero where, for the first time, we encounter two members of the same family simultaneously among the arvals. In his reign, the principle of inheritability may not have been abandoned, but it was restricted.31 Meanwhile, other participants in the cult of Dea Dia, such as the boys whose parents were still alive (pueri patrimi et matrimi), were largely recruited from outside this circle.32

The foundation of spatial foci was a sign of prestige among the Republican élite. Religion offered a welcome opportunity to immortalize political action under the pretext of piety. This is born out by the vast majority of temples vowed by generals in the course of their campaigns. It was no coincidence that in his funeral inscription, L. Cornelius Scipio singled out, as worth mentioning, the erection of a temple to the ‘Seasons’ (Tempestates), vowed on the occasion of his war with Corsica in 259 B.C., and built close to the family tomb of the Scipiones.33 And when the propraetor Q. Fulvius Flaccus promised a temple to Fortuna Equestris in the course of a fierce cavalry engagement with the Celtiberians in 180 B.C. (dedicated by him in 173), he was scarcely motivated by the desire to remedy the lack of a cavalry deity in the Roman pantheon.34 In the same vein, Q. Lutatius Catulus vowed a temple to Fortuna Huiusque Diei during the decisive battle against the Cimbri at Vercellae in 101 B.C. By its very nature, this hypostasis of Fortuna was bound to connote specific historical circumstances (i.e. hic dies). It therefore does not come as a surprise that it was dedicated on 30 July, the anniversary of Catulus’ victory.35 The fact that later writers refer to the resulting temple as aedes/monumentum Catuli36 illustrates without doubt the success of Catullus’ act of propaganda.37

It was not only individuals, but whole families that exploited the creation of spatial foci of cults for self-representational ends. Catullus’ sanctuary, for instance, is identified with Temple B in the sacred area of Largo Argentina, while next to it (scholars differ as to whether temple A or C) the temple of Iuturna had already been dedicated by a member of the same family more than a century earlier.38 A further example is that of L. Cornelius Scipio, who erected the temple of the Tempestates close to the family tomb of the Scipiones and as a reminder of his own deeds in maritime warfare.39 When M’. Acilius Glabrio consecrated a temple in 181 B.C. which had been vowed by his father ten years earlier, he promoted his family link by means of an inscription and a gilded bronze statue of his father on horseback, the first of its kind in Rome.40

Alongside spatial foci, the élite controlled all kinds of temporal foci in the public arena. This control was due not only to its occupation of the major priesthoods, but also to its exclusive representation in the senate. This institution was free to endorse or to reject virtually any establishment of spatial and temporal foci of divine concepts, most notably processions and public Games. The latter became increasingly a venue for public self-representation of ambitious members of the élite, who normally covered the expenses out of their own private funds.41

The expansion of the Roman pantheon by means of the creation of new spatial foci might more often than not disguise the self-representation of ambitious politician-generals or their families. Indeed, the nature of the deity chosen might have been a secondary consideration. This is clear in the case of M. Atilius Regulus, who vowed a temple to Pales on his campaign against the Sallentini in 267. Strangely, though, Pales, despite her venerable age, had no apparent connection to war. What mattered was not the goddess, but the occasion and the name of the founder of her temple, which was handed down by tradition in due course.42 A member of either the Metelli or the Aemilii (reading uncertain) vowed and dedicated a temple to an otherwise unknown god, Alburnus. Apparently this act of self-display, under the disguise of an otherwise completely unknown god, gave rise to strong feelings, for the senate responded by passing a law, according to which no temple vowed in war should be dedicated before it was endorsed by the senate.43 It was a natural step in the history of self-display of the élite when Caesar vowed a temple to Venus Genetrix before the battle at Pharsalus in 48 B.C. Unlike its inspiration, the sanctuary of Venus Victrix dedicated by Pompeius four years earlier,44 Caesar’s temple did not serve to commemorate a specific historic event, but to honour the divine ancestress of the leading statesman of the day (hence the epithet genetrix).45 Caesar’s initiative implied a shift of emphasis from the commemoration of individual success to that of successful individuals.

In terms of conceptualizing Roman gods (as in other areas), the Roman senate throughout its history remained conservative and suspicious of innovations. This conservatism was due to a need felt by the socially privileged to legitimize their status by traditional divine concepts, a form of conservatism famously labeled ‘theodicy of good fortune’ by Weber in 1920.46 A few years later, the famous sociologist summarized his earlier views: “What the privileged classes require of religion, if anything at all, is this legitimation.”47 ‘Theodicy of good fortune’ was clearly the reason why senators were among the last to embrace Christianity (only from Commodus onwards)48 and why no evidence has yet been found on Italian soil of senators practising the rites of Mithras before the fourth century A.D.49

In terms of religious attitude, equestrian families differed little from their senatorial counterparts. Cicero spoke of the “sacred rites” of his ancestors at Arpinum, which certainly included the worship of one or more deities favored by the family.50 One may point to the god Visidi-anus, belonging perhaps to the Visidii, who (in Rome at least) appear as an equestrian family.51 Furthermore, one may refer to Bona Dea Annianensis, who figures on a Roman inscription and can only with difficulty be dissociated from the Annii, another equestrian family.52 The same is true of the Octavii and the cult of Mars at Velitrae (some 30 kilometers south-east of Rome), as attested by Suetonius.53 When Augustus erected a temple to Mars Ultor in the centre of his new Forum Augustum, he also had in mind (apart from the obvious reference to Actium) his family affiliations with the god. He thus imitated Caesar’s sanctuary of Venus Genetrix in his Forum Iulium with its unmistakable reference to the ‘Iulian’ gens.54 It is conceivable that such identifications of specific gods with specific families were more widespread among equestrian families than the extant evidence might suggest. Apart from socialization and divine attention, such an identification would naturally assimilate the appearance of the equestrian families to that of their aristocratic counterparts.

Meanwhile, in the imperial period, some official priesthoods, such as the minor flaminates, minor pontificates, the curiones and others, were reserved in practice to members of the equestrian order, presumably after the reorganization of the order by Augustus.55 Generally speaking, the two highest orders were remarkably similar in their religious demeanour: both groups might favour certain gods according to family traditions and expediencies, and they eventually managed to secure the vast majority of official priesthoods almost exclusively for their members.

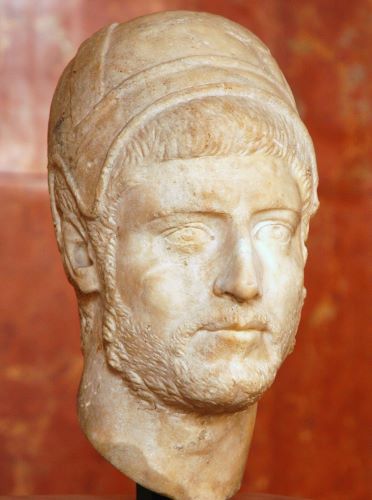

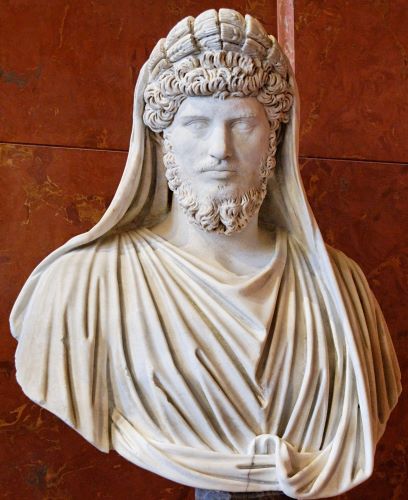

A special case among the Roman élite was that of the emperor. His presence on all levels of religious decision-making was particularly palpable. Caesar had already begun the cumulation of priesthoods by combining the highest pontificate with the augurate, and from Augustus onwards, all emperors were members of the four major priestly colleges, apart from minor official priesthoods (e.g. the Fetiales, Arvales, Augustales).56 Most important was, of course, the emperor’s position as pontifex maximus, which gave him de facto all-encompassing religious powers in Rome as well as throughout the Empire.57 The emperor thus controlled, even if only potentially, all religious decision-making, although he was much less interested in actual cult performance. This observation explains why emperors did not normally participate in regular sacerdotal meetings (there appears to be no evidence for such a direct participation of the emperor after 204 A.D.)58 and suggests a reason why, after Caesar, no emperor was interested in holding mere executive priesthoods, such as that of the Jovian flaminate.59

The emperor’s choices of gods among the pantheon were dictated primarily by two parameters, political expediency and personal predilection. Down-to-earth characters such as Augustus, Vespasian or Trajan would automatically act on the former, more lofty spirits such as Caligula, Domitian or most impressively Elagabal, would be drawn to the latter. For instance, the marked promotion of Apollo under Augustus had a political aspect (the battle at Actium) and a cultural aspect (Greek culture). Alternatively, one may point to the cult of Mars Ultor, established by Augustus, and with its political character already manifest in his name. At the other end of the scale we find Caligula who likened himself to Iuppiter, Domitian with his private faible for Minerva, or Elagabal who unsuccessfully tried to make Rome a theocracy under a non-Roman god.

It is important to note that any imperial choice of a specific cult, however remote from Roman custom, was an official choice. It served as a precedent, which entailed for the subjects both the right and the obligation to participate. One may again consider Mars Ultor, the Augustan divine concept par excellence (along with the Palatine Apollo). His temple had been erected by the princeps on private ground and with private funds (spoils of war). Despite its undoubtedly private character, it soon became one of the major foci of the Augustan public cult.60 Interestingly, in the long run Roman society after Augustus demonstrated an almost complete indifference towards imperial predilections. For no such predilection left long-term traces in the historical record of the city after the emperor’s death.

The Underprivileged

The lower strata of Roman society were virtually excluded from all official priesthoods. Towards the end of the first century B.C., when we find freedmen such as A. Castricius, son of a foreigner, or Clesipus Geganius, a freedman or freedman’s descendant, as personnel foci of one or even more than one official cult, they certainly had powerful patrons and considerable financial resources.61 At most, the lower strata would normally become auxiliary personnel in public institutions including priesthoods (apparitores), and as such, hold certain provincial priesthoods.62 Meanwhile, freedmen and women are attested in Rome as priests of Bona Dea,63 Isis,64 Cybele,65 Mithras,66 or unspecified gods,67 and certainly many more. But such priesthoods would largely, if not exclusively, be of an unofficial nature.

There are indications that some official gods were favoured by the lower strata, but the evidence is too arbitrary, scanty and biased (with the privileged classes much more likely than the underprivileged to document their beliefs in inscriptions or literary evidence) to draw any firm conclusions.68 Apart from official gods, the lower strata may have favoured a number of unofficial gods, for example Silvanus.69 The god did not have a place in the official calendar, nor an official priest or sanctuary in Rome. He is depicted on official monuments or coins no earlier than the beginning of the second century A.D.,70 despite his apparent popularity in the lower strata of predominantly male Roman society.71 Nevertheless, there are a few examples of the worship of the god by freemen, and even by members of the senatorial élite.72

The socially underprivileged were not only attracted to exotic rites. Magic, in all its forms, was popular among the lower strata of society (while the more educated may have preferred to turn to philosophy or to choose a disguised agnosticism). But members of the senatorial order and even members of the old patriciate also took a keen interest on occasion.73 Free Roman citizens, perhaps recruiting their leaders from noble families, participated in the exotic rites of Bacchus in 186 B.C.74 Laws were directed against participation of Roman citizens in the cult of Magna Mater; clearly an indication that such laws were deemed necessary due to the potential interest among the free popu-lation.75 From the moment of her arrival in Rome, Isis, while still an unofficial and suspicious deity, was worshipped by freedmen and Roman citizens—clients of major aristocratic families—alike.76 In 19 A.D., the cult was considered so dangerous by Tiberius that he deported 4,000 of its adherents (along with Jews) to Sardinia. Tacitus reports that all the deportees were freedmen.77 The relative absence of the unfree part of the population in inscriptions related to the cult of Isis is clearly due to the notorious financial straits of this stratum. But this absence is deceptive. The considerable number of freedmen among the Isiacs indirectly proves the participation of unfree persons in the cult, for one would not suddenly be drawn to Isis after being enfranchised.78 Some senators and knights may be counted among worshippers of the Egyptian gods, though it must be admitted that these cases appear to be relatively rare, even in the heyday of the cult of Isis in the second and third centuries A.D.79 The Dolichene Iuppiter, though certainly most popular among the underprivileged, especially the lower ranks of the army, nevertheless counted a consul among his adherents.80 Even Mithraism, despite its clear popularity among the lower strata, never became characteristic of the underprivileged.81

It is natural to assume that a master or patron influenced the religious behaviour of his servants or clients. As long as master and servants lived in the same household (as certainly they did in rural areas), the religious choices of the master are likely to have had considerable impact on his servile environment. There is, however, evidence for such impact beyond the boundaries of rural households. For instance, we possess a remarkable Republican dedicatory inscription to Fors Fortuna from the vicinity of Rome, set up by a professional corporation. Among the corporate members are mentioned a slave and a freedman of the gens Carvilia. What is remarkable is the fact that a consul of the same Carvilii is known to have dedicated a temple of Fors Fortuna in Rome in 293 B.C.82 Another case in point is that of a freedwoman of Livia, Augustus’ wife, Philematio by name, who was priestess of Bona Dea. Ovid attests to the close connection of Livia with the same goddess, whose Aventine temple the empress restored.83

Corporations (collegia), apart from their profane business, were involved in the regular worship of various gods, whether for protection of their economic interests or for other expediencies.84 The exact nature of many of these corporations is unclear, but the fact that they gathered around one or more deities clearly shows that they operated inter alia as corporate forms of personnel foci of private cults, whatever their actual raison d’être. An exceptionally clear example are the Mercuriales. Based in the Aventine temple of Mercury allegedly from the fifth century B.C. on, they clearly combined economic interests with worship of the god of commerce.85 Some of these corporations, such as the Bacchants in 186 B.C., seem to have been exclusively concerned with the cult of one specific god.86 The Bacchants were apparently also the first corporation against which the authorities intervened. Such interventions became more frequent from the middle of the first century B.C. onwards.87

Cult activities may normally have only been secondary to the corporations’ initial purpose, being employed simply to create and reinforce a sentiment of ‘community’.88 It is likely that most corporations, especially those who had placed themselves under the protection of a specific deity (as shown by their name), normally focused on one cult. However, such a focus on the patron deity would not automatically exclude the worship of other gods. For example, we find in the capital a Mithraic priest (pater) as well as another priest (sacerdos) of Silvanus, apparently as representatives of religious corporations, dedicating an altar to Iuppiter Fulgerator after the instigation of the ‘mountain gods’ (dei Montenses).89

All the gods of the pantheon, from the supreme Iuppiter Optimus Maximus90 to the unofficial Silvanus,91 could receive attention by cor-porate votaries. At the beginning of the imperial period, the under-privileged may have often been encouraged by the ruler himself to participate in the cultic activities of these corporations. The first ruler to encourage participation was apparently Augustus, who introduced worship of the Lares Augusti (and his genius?) in Rome in 8/7 B.C.: the officials in charge of this new cult were—like their Republican predecessors—freedmen (vicomagistri), and assisted by slaves (vicoministri).92

Both Jews and Christians tended to belong to the lower strata of Roman society during the period mentioned. The Jews were further marginalized topographically, because their quarters lay in Trastevere, outside the city walls.93 By the first century A.D., many Jews had acquired Roman citizenship, while this does not appear to be the case for the majority of the Christians.94 Weber thought that it was for its ‘theodicy of bad fortune’, that Christianity was initially restricted to the underprivileged strata of Roman society.95 In fact, even if the question cannot be definitely settled, it is more likely than not that the first Christians in the city were unfree or peregrine, or both.96 The next logical step was that Christianity attracted Roman freedmen.97 It was via the latter and most of all via the highly ambitious (socially and economically) flexible imperial liberti that Christianity eventually conquered the remaining strata of Roman society.

Women

Where women are found in Republican sacerdotal establishments, their appearance is carefully monitored by male priests. For instance, their most important representatives in terms of the official religion, the vestals, were answerable to the pontifex maximus, who wielded absolute power both in filling vacancies among their ranks and in administering disciplinary measures, including the death penalty.98 When female priests of Isis are found in Rome due to an Egyptianization of the cult, they are restricted to the lower grades within the cult. There is no evidence of higher-ranking female priestesses.99

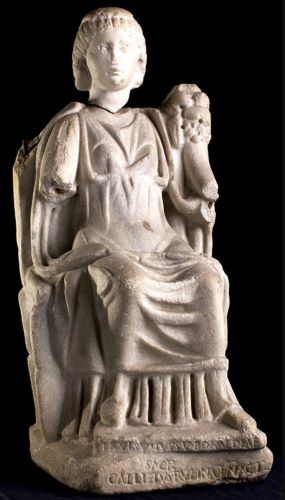

However, this does not mean that women were prevented from the official formation of divine concepts. Rather, they had their share through their personal influence and family relations, not by virtue of political power. An episode, the historicity of which (though not the historical plausibility) may be in doubt, illustrates effectively the mechanism behind such influence. At the beginning of the fifth century B.C. the appearance of Roman matrons, including his mother and wife, led Coriolanus to abandon his march on Rome. The senate showed its gratitude by granting the women a gift of their choice, on which the matrons voted for the erection of a temple to Fortuna Muliebris. The basic point of this story is that, due to a successful private initiative, Roman women brought about the establishment of an official cult from which only they themselves could reasonably benefit. Having said this, it is worth noting that their cult had still to be endorsed by the senate.100 Furthermore, Livy’s description of the Bacchanalia of 186 B.C. throws light on their involvement in religious decision-making at all levels of Roman society.101 Finally, in the Republic, the vestals could on occasion successfully—though unofficially—intervene in Roman politics.102 Besides this, women could satisfy their ambition in religious matters without further restrictions, by means of donations and all sorts of euergetism, in order to display social prestige and financial ease. In this, women hardly differed essentially from their male counterparts.103

As among men, initially patrician women held a dominant place in matters of state religion. Before the lex Canuleia, passed in the mid fifth century B.C., the wives of the major flamines (flaminicae) and of the rex sacrorum (regina sacrorum) had to be patricians like their husbands (after that date, they could have plebeian status).104 An episode (perhaps not historical, but historically plausible), recorded by Livy in 295 B.C., reveals that patrician women had their own cults (in this case that of Pudicitia Patricia), in which women of the plebeian aristocracy were not allowed to participate.105 The vestals, for the most part of the Roman Republic, are likely to have belonged to the Roman aristocracy and originally to the patriciate only. However, in 5 A.D. Augustus had to admit daughters of freedmen, because of the lack of available candidates.106

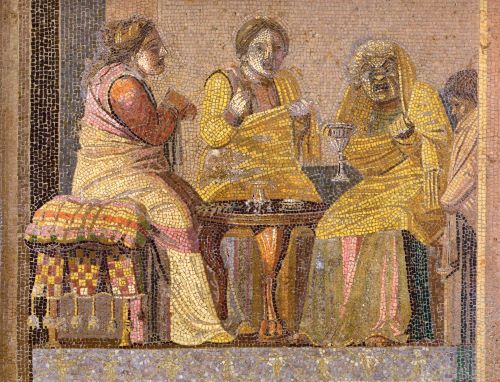

It was not so much the worship of specific deities, but specific rituals, often connected with specific locations or sanctuaries, that were sex-related: for example, the nocturnal mysteries of Bona Dea were reserved for noble women and the vestals.107 Nevertheless, there is ample evidence that men of all strata of society (especially the underprivileged) actually worshipped the goddess.108 Similarly, the worship of Bacchus at the Aventine sanctuary at the beginning of the second century B.C. was at first restricted to women (feminae), who were initiated there three times a year. Before the cult was opened up to men, priestesses were free maried women (matronae).109 However, men were not excluded in principle from the cult of Bacchus/Liber outsite this specific context, as is abundantly clear from the inscriptional material.110 To female prerequisites one may add a number of official festivals, often connected with fertility and motherhood, which were largely performed by women, for instance the Matronalia dedicated to Iuno Lucina.111 In no case, however, does the exclusion of men from such specifci ceremonies indicate a principal debarment of men from the cults of the relevant deities.112 A further case in point is the annual offering of the first-fruits to Ceres, which was performed by Roman matrons,113 while the cult of Ceres as a whole (for instance at the Cerialia) was, of course, not restricted to them.

The same is true the other way around: for instance, the fact that women were excluded from worship of Hercules Invictus at the Ara Maxima does not mean that women could not in principal appeal to the god in other contexts (although they would not do so normally).114 Another case is that of Silvanus/Faunus, predominantly believed to be a ‘male’ god with specific places dedicated to him and explicitly reserved to men.115 Nevertheless, dedications by women to him are well attested in Rome and elsewhere, despite the existence of his female counterpart Fauna. Such dedications by women to him, rather than to his female counterpart, give the lie to literary evidence which claims that the worship of Silvanus/Faunus was reserved to men.116 It should also be noted that lower class women participated in a number of corporations (collegia) of the underprivileged that are mentioned above. In such cases, women must have worshipped the same corporate gods as men.117 The only god that appears to have been fundamentally male-oriented, in the full sense of the word, was the cult of Mithras.118 In short, specific ceremonies or cult places may have been exclusive (especially if such exclusion was officially sanctioned). In addition, certain deities may have attracted one sex more than the other, due to gender-specific competences (e.g. childbirth, motherhood, war). But with the possible exception of Mithras, any god of the Roman pantheon could be—and for the most part actually was—worshipped by either sex.

When we consider the case of the Christian community in Rome, a special place must be reserved for female followers. Women of the underprivileged strata of society played a remarkable, if not the dominant role among Roman Christians in the mid-first century A.D., as has been plausibly inferred from Paul’s Epistle to the Romans.119 However, a little later, towards the end of the century, the first Epistle of Clement explicitly restricts the active involvement of women,120 although in practice they remained a dynamic element in the Christian community in Rome in the second century A.D. Whatever their actual access to decision-making bodies, by 200 A.D. the percentage of confessing female Christians in Rome was appreciably higher among the senatorial class than among the underprivileged strata; this caused complications with regard to the admissibility of unions between senatorial women and lower-class men.121

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Chapter 4 (167-185) from Roman Gods: A Conceptual Approach, by Michael Lipka (Brill, 04.30.2009), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license.