The belief that nobody really does or can know anything is the perfect soil for an authoritarian leader to take root.

By Dr. Rebecca Gordon

Adjunct Professor of Philosophy

University of San Francisco

In one of the Bible stories about the death of Jesus, local collaborators with the Roman Empire haul him before Pontius Pilate, the imperial governor of Palestine. Although the situation is dire for one of them, the two engage in a bit of epistemological banter. Jesus allows that his work is about telling the truth and Pilate responds with his show-stopping query: “What is truth?”

Pilate’s retort is probably not the first example in history of a powerful ruler challenging the very possibility that some things might be true and others lies, but it’s certainly one of the best known. As the tale continues, the Gospel of John proceeds to impose its own political truth on the narrative. It describes an interaction that, according to historians, is almost certainly a piece of fiction: Pilate offers an angry crowd assembled at his front door a choice: he will free either Jesus or a man named Barabbas. The loser will be crucified.

“Now,” John tells us, “Barabbas had taken part in an uprising” against the Romans. When the crowd chooses to save him, John condemns them for preferring such a rebel over the man who told the “truth” — the revolutionary zealot, that is, over the Messiah.

What, indeed, is truth? As Pilate implies and John’s tale suggests, it seems to depend on who’s telling the story — and whose story we choose to believe. Could truth, in other words, just be a matter of opinion?

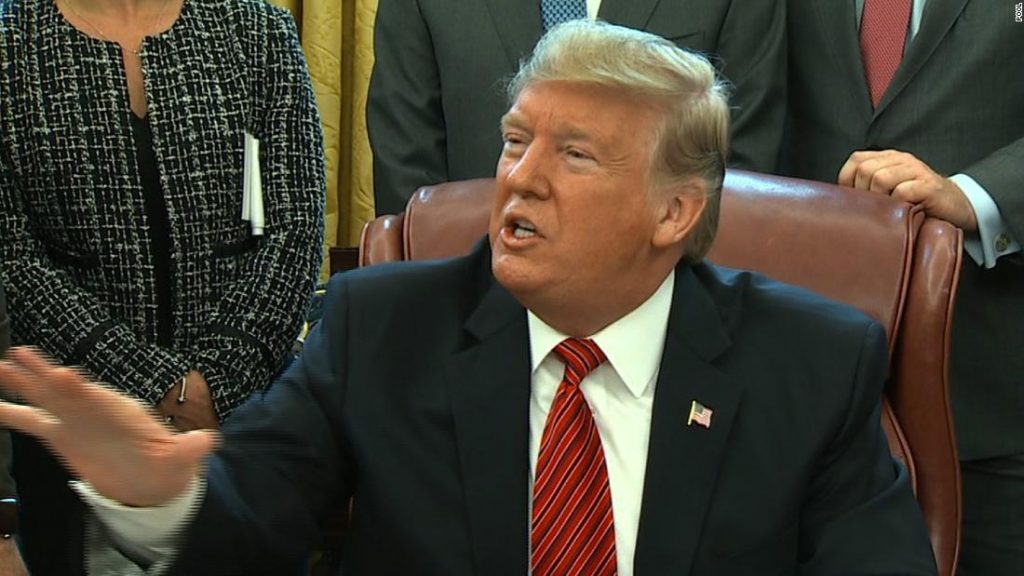

Many of my undergraduate philosophy students adopt this perspective. Over the course of a semester, they encounter a number of philosophers and struggle to understand what each is arguing and what to think when they contradict each other. I do my best to present scholarly assessments of the strengths and weaknesses of these varying approaches, but all too often students find themselves drowning in a pool of epistemological confusion. If a philosophy can be criticized, they wonder, how can it be true? The easiest solution, they often find, is to decide that truth is indeed just a matter of opinion, something that has only become easier now that Donald Trump sits in the Oval Office.

A more difficult route out of the morass would be to trust themselves to evaluate the claims of competing theories of how life works and decide, however tentatively, which seems most convincing. But it’s precisely the skills needed to evaluate such competing claims that many of them lack. Often, they doubt that such skills even exist. In this, they are not unlike President Trump who is frequently astonished to learn things that ought to be part of an ordinary citizen’s knowledge base. (Apparently, until he personally stumbled upon the fact, for example, “nobody knew that health care is complicated.”) Their answer to most questions is some version of “nobody knows” or indeedcan know; truth, in other words, is just a matter of opinion.

This popular belief that nobody really does or can know anything is the perfect soil for an authoritarian leader to take root.

But facts really are, as the popular expression has it, “a thing.” Try telling a former resident of Paradise, California, that truth is just a matter of opinion when it comes, for example, to climate change. Paradise, you probably remember, was the town in Butte County that was incinerated last November by the deadliest wildfire in California history. Or rather the deadliest so far, since there can be no doubt — if you don’t happen to be the president or his climate-change-denying Republican colleagues and cabinet members or part of the 20% of Americans who still refuse to believe the obvious — that worse is to come. After all, as the Associated Press reported recently, 15 of California’s 20 “most destructive” wildfires have burned in the last two decades.

For President Trump, whether or not the global climate is changing is not a question to be answered by examining evidence. “People like myself, we have very high levels of intelligence but we’re not necessarily such believers,” he told the Washington Postthat very November, adding, “As to whether or not it’s man-made and whether or not the effects that you’re talking about are there, I don’t see it.”

To Trump, what is clearly the worst danger threatening humanity is a matter not of fact, but of belief, and possibly even a complete fiction.

From Credibility Gap to Alternative Facts

Donald Trump is hardly the first American president to have a loose relationship with the truth. Back in the 1960s, when the Vietnam War was raging, what was then dubbed the “credibility gap” opened in the minds of journalists and the public — a gap between President Lyndon Johnson’s assertions about “progress” in that war and “the facts on the ground.” Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, who co-directed PBS’s 10-part series on that war, argue that “this radical diminution of trust” in the presidency began with Johnson’s, and later President Richard Nixon’s lies to the American public about what was actually going on there.

Those lies included a specious casus belli and legal underpinning for the full-scale American intervention there (supposed North Vietnamese attacks on two U.S. destroyers in the Gulf of Tonkin). Even the State Department’s official online history now acknowledges that “doubts later emerged as to whether or not the [second] attack… had taken place.” As the war progressed, two administrations rolled out ever more lies about the victory soon to come, especially via post-battle body counts, often presented like sports scores in which the winner was the one with the lower number: Americans, 78; Viet Cong, 475. Miraculously, the U.S. military never appeared to lose a match, which made the public all the more surprised when they lost the war itself.

In the Vietnam years, at least, such a credibility gap could be acknowledged and an administration forced to confront it. Despite the fact that media outlets now almost routinely tote up Trump’s “untruths” — his misstatements, false statements, and lies — by the thousands, his administration has managed to call into question the very existence of any “facts on the ground” whatsoever. This process began in the most literal way on the first day of the Trump era: his inauguration. In January 2017, White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer insisted that Trump had drawn “the largest audience ever to witness an inauguration, period, both in person and around the globe.”

When journalists began comparing photographs of the crowds at Trump’s and Barack Obama’s inaugurations — the literal facts on the ground — it became clear that Spicer was lying. (The photos of the Trump inaugural would later be “edited” to fit the president’s desired reality.) Some of us wondered: Would that moment mark the opening of a new credibility gap for the Trump era? And the answer would be: no, it would signal the beginning of something even worse.

In the epistemological universe of the president and his base, a credibility gap is inconceivable, because there are no facts on the ground to begin with. Or rather, we are invited to choose from a range of “alternative facts,” as Trump aide Kellyanne Conway so unforgettably put it. His press secretary can’t lie, no matter what the (unedited) aerial photos of those crowds may show, not when what you might perceive as a lie is simply someone else’s statement of alternative fact.

Trump’s is not the first administration in recent memory to suggest that truth is a matter of what you choose to believe — or, if you prefer, a matter of faith. In “Faith, Certainty and the Presidency of George W. Bush,” a 2004 New York Times Magazine article, journalist Ron Suskind reported on discussions among various administration insiders about the president’s worldview. An unnamed former aide to Ronald Reagan assured Suskind, for instance, that, for President Bush, truth was in fact absolute. It just wasn’t based on evidence:

“This is why George W. Bush is so clear-eyed about al-Qaeda and the Islamic fundamentalist enemy. He believes you have to kill them all. They can’t be persuaded, that they’re extremists, driven by a dark vision. He understands them, because he’s just like them…

“This is why he dispenses with people who confront him with inconvenient facts. He truly believes he’s on a mission from God. Absolute faith like that overwhelms a need for analysis. The whole thing about faith is to believe things for which there is no empirical evidence.”

A Bush aide (later identified as key adviser Karl Rove) similarly disparaged evidence-based reality, though in his case by favoring facts created not through faith but power. As he so resonantly explained to those stuck “in what we call the reality-based community”:

“That’s not the way the world really works anymore. We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality — judiciously, as you will — we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors… and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.”

Everything Is Possible and Nothing Is True

Not surprisingly, among its critics Donald Trump’s presidency has inspired any number of references to political philosopher Hannah Arendt’s description of the dismantling of truth by authoritarian regimes of the previous century. In her 1951 book, The Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt described the process this way:

“In an ever-changing, incomprehensible world the masses had reached the point where they would, at the same time, believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and that nothing was true… Mass propaganda discovered that its audience was ready at all times to believe the worst, no matter how absurd, and did not particularly object to being deceived because it held every statement to be a lie anyhow.”

Our aspiring authoritarians (and the Russian internet trolls who assist them) understand this strategy well: Was Barack Obama born in the United States? Nobody knows for sure, but many people believe he wasn’t. Did Hillary Clinton run a secret pedophile ring from the basement of a Washington pizzeria? Nobody knows for sure, but some people believe she did. Do the Obamas have a 10-foot wall around their Washington home, suggesting that, according to the president, the entire country just needs a “slightly larger version” of the same on its southernmost border? Nobody knows, and in any case, how can we believe a photo of the house without such a wall offered by the Washington Post? Photos, after all, can easily be faked. Did Russia interfere in the 2016 presidential election? Nobody knows for sure, not even Donald Trump, despite having been shown substantial evidence that it did.

The cumulative effect of a mounting number of claims about which “nobody knows” the truth is a corresponding rise in the belief that nobody can know what is true. All evidence is equally valid (or invalid), so what’s real is as optional as the possible endings in a “choose-your-own-adventure” TV show.

If the world was “ever-changing” and “incomprehensible” to “the masses” in the authoritarian regimes of the twentieth century, how much more incomprehensible is the turbo-charged, Internet-fueled world of 2019? Today’s propaganda can be not only omnipresent but precisely tailored to specific audiences, even if its objectives (and often sources) may not be obvious at first glance.

We are used to thinking of propaganda (a word whose Latin roots mean “towards action”) as intended to move people to think or act in a particular way. And indeed that kind of propaganda has long existed, as with, for example, wartime books, posters, and movies designed to inflame patriotism and hatred of the enemy. But there was a different quality to totalitarian propaganda. Its purpose was not just to create certainty (the enemy is evil incarnate), but a curious kind of doubt. “In fact,” as Russian émigrée and New Yorker writer Masha Gessen has put it, “the purpose of totalitarian propaganda is to take away your ability to perceive reality.”

Eroding the very ability to distinguish between reality and fantasy has been, however instinctively, the mode of the Trumpian moment as well, both the presidential one and that of so many right-wing conspiracy theorists now populating the online world. When everybody lies, anything can indeed be true. And when everybody — or even a significant chunk of everybody — believes this, the effect can be profoundly anti-democratic.

Such belief, born of the relentless rush of falsehoods and conspiracy theories, doesn’t just rile people up and make them wonder what in the world is true. It also generates a yearning for a single voice to rise above the crashing waves of claims and counterclaims, a voice that can be trusted.

In a world in which people sense that truth no longer matters, it doesn’t make a difference whether what that voice says is true. What matters is that the voice is strong and confident. What matters is that it is authoritative even in its falsehoods. And if that reminds you of Russia’s Vladimir Putin or Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines or Brazil’s newly inaugurated hard-right president Jair Bolsonaro, or Donald Trump, it should.

Why Telling the Truth Matters

Most of what we know, we learn not through personal experience, but because of the reports of other trusted human beings. I have never performed the double-slit experiment, but I know that electrons can behave both as particles and waves. I haven’t recorded ocean or air temperatures over the course of a century, yet I know that on average, the Earth’s air, land, and waters are growing dangerously warmer.

It’s because so much of what we know depends on the truthfulness of others that the philosopher Immanuel Kant believed lying was always wrong. His reasoning was that when we lie to another person, we fail to respect her infinitely valuable capacity to encounter the world and think about the moral choices she’ll make in it. By refusing to tell her the truth, we treat her not as a person, but as an instrument — a tool to get something we want. We treat her like a thing.

I suspect that Kant was right, although one of my other favorite ethicists, Miss Manners (the journalist Judith Martin), argues that certain fictions (“this is delicious!”) are the lubricant without which society’s wheels would freeze in place. Perhaps — you knew I was going to say this! — the truth lies somewhere in between.

However, I am certain of one thing: that truth-telling is the bedrock of democracy. When we routinely assume that our fellow citizens and government officials are lying, it becomes impossible to work together to determine how our neighborhoods, our cities, or our country should function. When we abandon the effort to figure out what is true, we cede the field to anti-democratic leaders who derive their “just powers” not “from the consent of the governed” but from the acquiescence of the willingly deceived.

Anyone who has tried to tell the truth consistently knows how difficult it is to do so. The temptations to lie are powerful, in politics as in daily life. As the poet Adrienne Rich wrote in “Women and Honor: Some Notes on Lying,” when we claim we are lying because we don’t want to cause pain, what we really mean is that we don’t want “to have to deal with the other’s pain. The lie is a short-cut through another’s personality.”

Similarly, in democratic politics and organizing, the lie is a shortcut through the hard work of listening to other people’s arguments and formulating our own. Suppose your senatorial candidate (like the one for whose election I recently worked) favors raising the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour. It’s tempting to promise potential voters (especially the many voters who don’t know what a senator can and can’t do) that if your candidate wins, their wages will definitely rise. Electing your candidate may indeed make that more likely, but it’s hardly a guarantee.

In the short run, promising that wages will go up wins more elections than saying they might. But in the long run, this kind of shortcut drives people out of the democratic process, because they stop believing that candidates ever keep promises.

Even in a life-or-death campaign (such as the effort to unseat Trump will be, if he’s still around in 2020), we need to build democratic relationships based on telling the truth as well as we know how. Only if we can trust each other to try to be honest can we hope to rebuild something resembling a truly functioning democracy. Otherwise, sooner or later this country will be seduced by the siren song of yet another strong and authoritative voice.

Humans are finite creatures and any truth we lay claim to will of necessity be partial, multi-faceted, and complex. At our best, we see only part of what is there and articulate only part of what we see. The promise of democracy — when it works — is the possibility of combining all those partially glimpsed and imperfectly reported realities into a still imperfect, but nevertheless better, whole.

Originally published by Common Dreams, 01.10.2019, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 license.