This is a story of four different skulls that reached three of the world’s largest museums under less than transparent circumstances.

By Dr. Jane MacLaren Walsh and Dr. David Hunt

Walsh: Anthropologist Emeritus, Smithsonian Institution Museum of Natural History

Hunt: Professional Lecturer in Anthropology, George Washington University

Introduction

This is a story of four different skulls that reached three of the world’s largest museums under less than transparent circumstances—a fact that was mildly ironic given that three of these skulls were carved from rock crystal, and only the fourth is an actual human cranium. Perhaps more notable is that all of them have been thought, at various times, to be that bane of museum collections: frauds.

The three quartz skulls, popularly known as crystal skulls, were all sold in the nineteenth century as ancient Aztec carvings by the French antiquarian Eugène Boban (1834-1908). Two found their way to the Trocadero in Paris in 1878 after they had been exhibited at the Exposition Universelle. The third skull was sold to Tiffany’s in New York City in 1886, and purchased by the British Museum in 1898.

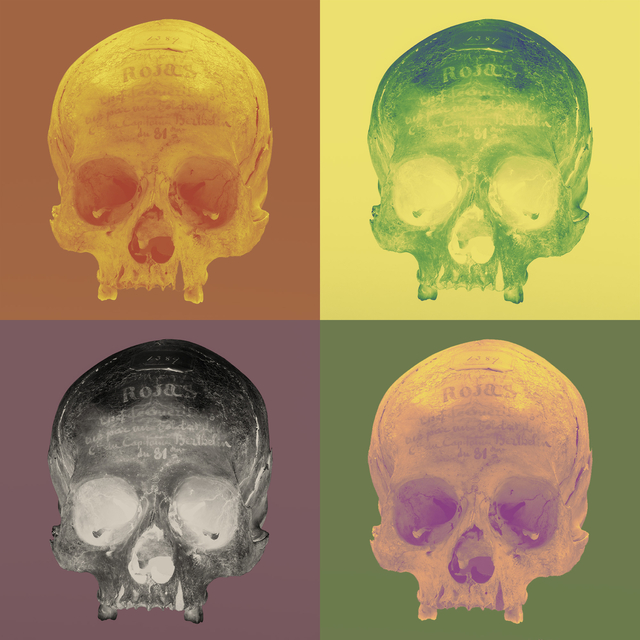

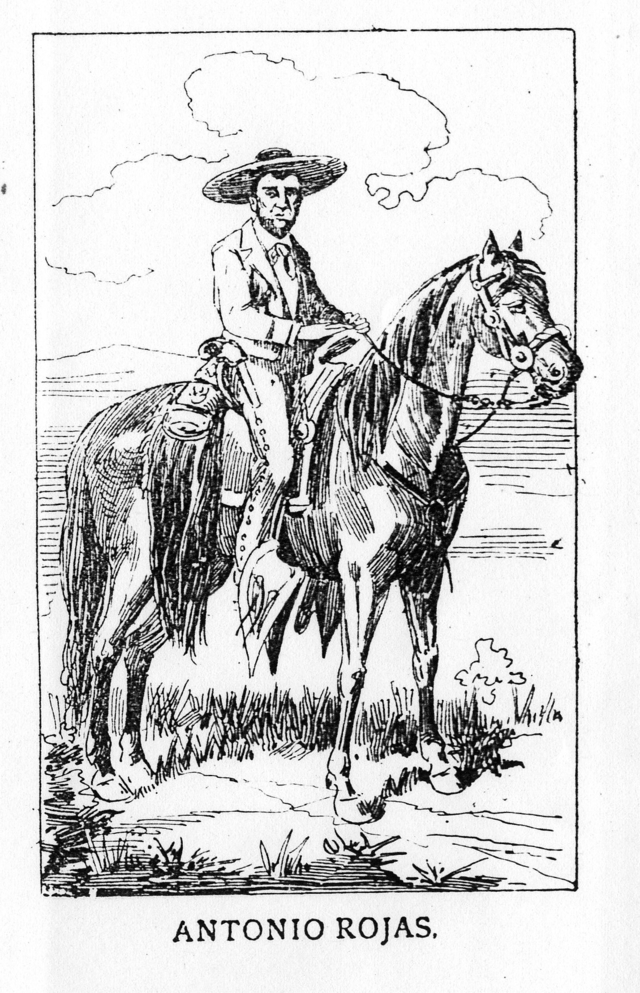

The story’s fourth skull was apparently that of a notorious Mexican bandit named Rojas, who fought off French invaders, and was shot in the back in 1865. On this diminutive skull’s forehead is a legend, identifying it as “Mexique—Rojas—Chef de Guerillas—tué par un soldat cie. du capitain Berthelin du 81e.” There are also several catalogue numbers inscribed upon it but, strangely, there is also a Venus symbol, signifying that the skull was also thought at one point to have been female. Perhaps it wasn’t Rojas at all. The Army Medical Museum purchased it in 1887 from the very same Eugène Boban, and transferred it to the Smithsonian Institution’s physical anthropology collections in 1904.

The quartz skulls eventually raised the eyebrows of anthropologists for two reasons. First, rock crystal is exceedingly rare in pre-Columbian collections, and no crystal skull has ever been excavated in a controlled archaeological dig. And second, because of the man who sold them all: the amateur archaeologist, collector and dealer Eugène Boban, who lived in Mexico from 1853 until 1869. The story of how he sold his crystal skulls to important national museums—and what those skulls actually were—is one that has taken over a century to unfold. The unraveling of the mystery is well known and has been extensively written about by one of the authors, Jane Walsh. The after-effect of that story, however, was a need to understand the nature and authenticity of other artifacts Boban sold to the world’s museums, which number in the thousands. The bandit’s cranium, studied and evaluated in 2012, initially also appeared suspect. Its story, however, turned out to be even more dramatic, amplifying a moment in the history of imperialism and resistance in the Americas.

This is a tale of four skulls, but it is also the story of authenticity and fakery in the imagined ruins of the Mexican past, conjuring images of pre-Columbian sacrificial victims, bloody bandits and betrayal—a history of illusions unlocked by twenty-first century science.

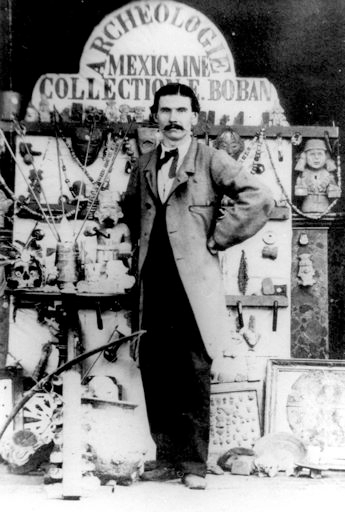

Digging for Treasure

When he arrived in Mexico City in 1857, fresh from the California gold fields, Eugène Boban was still hoping to strike it rich. He’d left Paris as an unemployed nineteen-year-old just ahead of Napoleon III’s draft, and though he hadn’t struck gold, he acquired two things that proved more valuable in the long run: a second language, Spanish, and an appreciation of the native peoples of the Americas. As it happened, Mexico was the perfect place to put these talents to use, and he was able to invent a new career and a new life.

Then as now, remnants of Mexico’s history remained close to the surface. Everywhere he walked, Boban found objects linked to the country’s ancient past. He befriended Indians living in and near Mexico City, who showed him likely places to dig and taught him a third language, Nahuatl. The country was a treasure house where the artifacts of past civilizations were his for the taking—or so he believed. He soon made a comfortable living selling artifacts to tourists and foreign dignitaries, and his earnings allowed him to purchase, for a relative pittance, thousands of pages of early colonial documents and numerous first editions on Mexican history, languages and culture. The books and manuscripts he amassed were his university education, and he eagerly devoured their contents.[1]

Boban’s arrival in Mexico coincided with the War of Reform (1857-1861). That civil war culminated in the election of President Benito Juarez, a Zapotec Indian who hoped to reverse the country’s racial, class, and economic inequalities. Juarez particularly sought to diminish the wealth and power of the Mexican Catholic church, which had allied itself with the conservatives who opposed his rise to power. As a budding entrepreneur, Boban would profit from this confrontation in a number of ways.

The Spanish conquerors had destroyed or overlaid the temples and ‘idols’ of the indigenous people, and now in 1861, Juarez laid siege to the Christian temples that had been built atop the Aztec structures. The great sixteenth-century church and monastery of San Francisco, just two blocks from Boban’s business, was entirely dismantled; its art, library and gilded choir were removed to make room for a cavalry stable. And that was just the beginning. More than forty religious structures were razed during Juarez’s presidency. To raise money to pay the debts incurred during the War of Reform, the Juarez government sold off much of the contents of the demolished buildings, often for a fraction of their worth. “The sale of Church property was a comedy played out between shrewd dealers and money launderers, a dramatic case of fraud, the state giving huge advantages to the purchasers,” writes one historian. W.H. Bullock, a British businessman, noted that there was a fairly limited market for religious artifacts because conservative Mexicans feared excommunication if they purchased any of the art. However, there were foreigners who “were willing to pocket their scruples and invest in it … many Frenchmen and Belgians, and some English, realized considerable fortunes.”

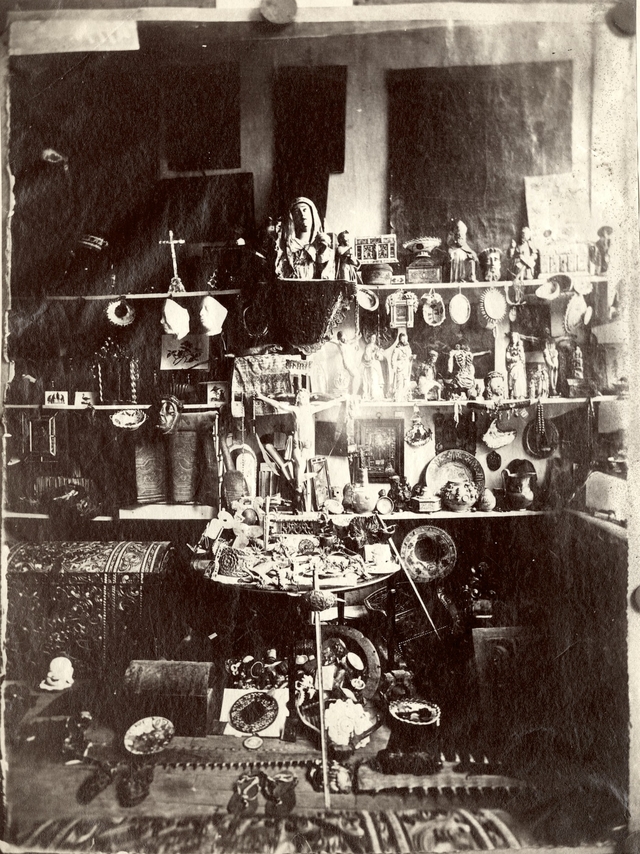

Judging from photographs of his shop, Boban was among those who took advantage of the situation, and by the late 1860s he had acquired a large collection of religious art and Spanish colonial artifacts in addition to his archaeological artifacts. Religious paintings lined the walls behind the shelves, which in turn hold figures of saints and the Virgin, and ornate crucifixes. There are also textiles, cups and chalices and numerous other valuable items.

By the end of Juarez’s first year in office Spain, Great Britain, and France invaded Mexico to exact payment of loans they had made to the reform government. England and Spain soon departed, but France, then governed by Napoleon III, remained. After an initial Mexican victory at the Battle of Puebla on May 5, 1862—now commemorated as Cinco de Mayo—the French General Bazaine defeated the Mexican forces. President Juarez fled Mexico City with his cabinet on the last day of May 1863.

The Mexican church and its allies had encouraged the French intervention, and now “sought to broaden their scope into a full-fledged invasion that would replace Juárez with a foreign ruler, who would support their conservative program.” The French government, in consultation with the conservatives, installed Maximilian of Austria as Emperor of Mexico. A member of the Habsburg family, Maximilian was related to the Spanish royalty that had ruled Mexico for almost three hundred years.

At the time of the French intervention Eugène Boban had already spent eight years in the country. With his cache of pre-Columbian artifacts and historical knowledge, he was perfectly disposed to act as an expert on Mexico’s prehistoric past, and in 1865 the French duly named him an archaeological consultant to Napoleon III’s Commission Scientifique. Boban began advertising himself as “antiquarian to the Emperor,” and a notice for his Curiosities and Antiquities shop appeared in a business directory of the newly formed Mexican Empire. Among the items listed for sale were stuffed birds, ceramics, paintings, weapons, Chinese porcelains, and Aztec antiquities.

The Commission Scientifique eventually sent a selection of Boban’s pre-Columbian artifacts to Paris for exhibition at the Exposition Universelle in 1867 to illustrate the achievements of the Empire. Boban hoped to use the exhibition as an advertisement for the collection’s sale to the Louvre. Unfortunately, in the midst of the Exposition news came from Mexico that Maximilian had been executed and that Benito Juarez had re-assumed his office as president. Maximilian’s death cast a pall over all things Mexican, dashing Boban’s hopes for selling his collection in France. At the close of the Exposition, the collection was given to Boban’s family for safekeeping; his mother encouraged Boban to come home and make provisions for its sale.

After a sixteen-year absence including twelve years in Mexico, Boban sailed from Veracruz to Paris in March of 1869. His friend Dr. Francisco Fenelon wished him bon voyage, and encouraged the successful sale of his collection, writing, “Flood France with your curiosities, and squeeze all the ugly metal out of them that you can in exchange …”

Aztecs in Paris

A few months after his return, Boban opened a shop called Antiquites Mexicaines. It was situated around the corner from the Sorbonne and across the street from the Musée de Cluny, a medieval monastery that had opened as a public museum in the 1840s. This carefully chosen location promised access to scientists and historians and he soon established himself as an authority on pre-Columbian artifacts and other antiquities despite his lack of formal education.

Boban’s shop glittered as much for its contents as its owner’s knowledge. Boban’s original pre-Columbian collection contained several thousand artifacts, including numerous large stone Aztec and Toltec icons and fine pottery from the central valley of Mexico, rare ceramic figurines from Veracruz, and distinctive stone masks from Teotihuacan. It was the largest and most important collection in Europe at the time. A porphyry carving of Quetzalcoatl depicted as a man enveloped in a feathered serpent is of exceptional quality and interest. It included more than a hundred Remojadas figurines from Veracruz—their smiling heads never before seen by scholars and students. The stone masks from Teotihuacan are exemplary and highly instructive; Boban himself appears to have excavated them. A jadeite mask depicting the face of a flayed victim, acquired from the Museo Nacional, is a beautifully executed and chillingly powerful portrait.

The thirty-five-year-old antiquarian may have believed that he would sell his collection quickly and return to Mexico a rich man. He had left a wife there, who was looked after by his friend Dr. Fenelon. She is mentioned in a letter written by Col. Dutrelaine, head of the French Scientific Commission in Mexico, who described Boban as “a little married” to a woman from Chiapas. We don’t know if she was a native Maya speaker or a Mestiza; we don’t even know her name. We do know that she was the first of three women Boban may or may not have married.

Unfortunately, Boban had arrived in Paris at the worst possible time for such a venture. It was just before the Prussian army laid siege to the city, a disaster that was soon followed by the Commune Revolt. It would take six years before his first major sale was concluded, in 1875, when Alphonse Pinart, a well-connected linguist, ethnographer, and explorer, purchased most of Boban’s pre-Columbian collection. Pinart then made a deal with the French government to give this newly purchased collection to the Trocadero, in exchange for government funding for his planned expeditions to America and the Pacific. Although Pinart benefited quickly from the purchase and donation of Boban’s collection, Boban would not actually receive payment for the sale until the end of 1879. Sadly, his Mexican wife had died in 1873; his original plan of returning to see her was defeated on all counts.

When the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadero in Paris opened to the public in 1882, Boban’s Mexican pre-Columbian material (bought and donated by Alphonse Pinart) was the museum’s premier New World archaeological collection. Despite the disasters of the invasion of Mexico, the French remained fascinated with pre-Columbian cultures, particularly the exotic depictions of gods and goddesses with their elaborate and lugubrious iconography. Boban played on that romance, and became an advisor to Ernest T. Hamy, the director of the Trocadero, on matters relating to his collection.

Boban also became known as a source for skulls. French anthropologists were particularly fascinated with craniometry, the scientific study and measurement of human skulls, and many scientific societies had their own collections. In addition to his pre-Columbian artifacts, Boban had also collected human skeletal remains from his Mexican digs, which he eventually sold and donated to a variety of museums in Europe. Boban corresponded with Paul Broca, the physician, anatomist, anthropologist, and founder of the Laboratoir d’anthropologie; Boban took courses from him, frequented his lectures, and sold him a variety of artifacts, in addition to donating skulls to his laboratory.

Today, however, Boban is known for a different sort of skullduggery: despite the fact that he collected thousands of important and authentic artifacts from countless sites in Mexico, his most famous objects—his crystal skulls—are fakes. At the time, however, they were greeted as astoundingly, importantly real. During Boban’s lifetime the director of the Trocadero’s ethnographic museum, Hamy, published two separate articles on Boban’s flashiest fakes: two crystal skulls and an obsidian plaque with the date 1347. In his publication marking the 400th anniversary of the discovery of America, Hamy described the large crystal skull as possibly a pendant from the mantle of one of the Aztec gods.

Hamy was fooled, but he was hardly alone. Verifying the authenticity of rock crystal artifacts was problematic from the start. Because Europeans found crystal objects so appealing, they were predisposed to believing in their importance and authenticity in a pre-Columbian context. This was despite the fact that quartz was quite rare in Mesoamerican archaeological collections. Aside from the small crystal goblet from Monte Alban’s Tomb 7, documented rock crystal objects in Mexico are confined to beads and labrets.

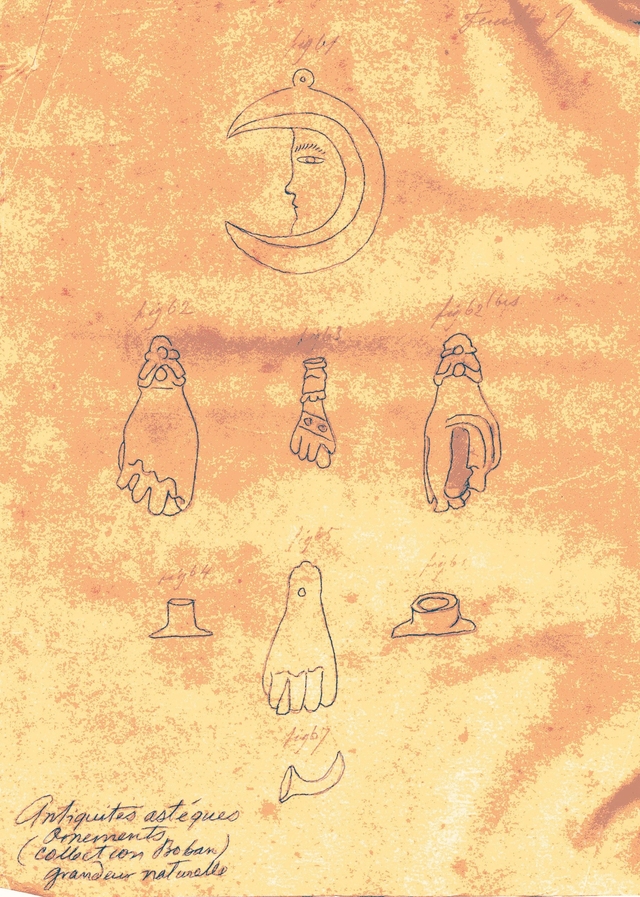

But was Boban himself taken in? Did he know that he was selling fakes? Or was he part of the trick? Although Boban published on a number of important and authentic pieces that he had collected over the years, he studiously avoided his problematic pieces, and drawings of his material that he sent to Europe suggest that he had some difficulty in deciding which crystal objects were actually pre-Columbian. A few of the crystal objects were shaped like human skulls, but others were carved fists, and another was a crescent-shaped object, an image of the man in the moon. The fists, or mano fico, and the man in the moon are European concepts; Aztecs imagined rabbits on the moon and the fist amulets were not part of their iconography at all. As such, these objects were clearly misidentified. Boban would deal in crystal objects throughout his career, benefiting from the allure of the material, but their very mystery cast a shadow on his reputation as a dealer and scholar.[2]

The two crystal skulls sold by Boban to Pinart, one the size of a grapefruit and the other the size of a grape, were exhibited in 1878 at the Exposition Universelle, and are both still in the Musée du quai Branly. The larger skull was not part of the original 1867 exhibit, and was either brought to Paris by Boban in 1869 or acquired by him there at some later date. Already these skulls were proving to be somewhat problematic for Boban’s reputation. A description of the 1878 exposition notes, “One can also see a representation of a human skull in rock crystal, which comes from the Boban collection acquired by M. Pinart. But the authenticity appears doubtful.”

Boban was by no means abashed. His business grew over the years, and by 1878 his catalogs advertised objects from all over the world. In 1881 he offered another, much larger human skull carved from the purest quartz crystal for the substantial sum of 3500 francs. The skull was listed in a section entitled “objets divers”—not as part of his archaeological material from Mexico or the Americas. Yet, despite the allure of rock crystal and skulls, this object didn’t sell. Perhaps the price was too high. A few years later, however, Boban would make the skull appear not only more valuable, but also exotic and ancient.[3]

“Unique in All the World”

In February of 1885, Eugène Boban, fifty years old now, finally returned to Mexico City. With his second wife, he opened a private museum he called the Museo Científico. It contained four exhibit halls. The first contained ethnographic exhibits from North and South America, Africa and Oceania. The second held a library of more than a thousand volumes on prehistory, archaeology, geology, mineralogy, etc. The third room displayed Boban’s extensive archaeological collections from Mexico, North America, Peru, Egypt, Italy and Greece, along with European paleontology. And the fourth exhibit room was dedicated to craniometry or physical anthropology. It contained four “historic mummies” from the Mexican convent of Santo Domingo, which had been found in 1861 and were described as “victims of the Inquisition.” In addition, there was the mummy of a “young Egyptian prince” dating to 1643 BC, along with a series of human skulls that, according to Boban, represented the ancient populations of Mexico as well as other regions. Also featured in this section was “a life-size rock crystal skull (quartz hyaline) unique in all the world.”

In the bizarre display above, two of the Santo Domingo mummies, covered with white cloths for modesty’s sake, are laid out in velvet lined coffins, beneath a canopy supported by four ornately carved columns, a sort of catafalque. There is an arrangement of human skulls at the foot of the coffins. Just behind the coffins is a table containing more human skulls described as ancient people of Mexico, and a label reading “Craneo de Cristal de Roca,” which can be seen in the enlargement below. The crystal skull can be made out in the center just behind the other crania. It has a shine to it, and seems to be set on a pedestal.[4]

That skull, however—purchased in Paris—would lead to Boban’s abrupt departure from his adopted home. In March of 1886, William Wilberforce Blake, an American official of the Mexican Railroad, collector and sometime journalist, wrote a letter to William Henry Holmes, an archaeologist at the Smithsonian Institution, filling him in on local gossip. Holmes, who had visited Mexico in 1884, had asked Blake about archaeological work being done at Teotihuacan by Leopoldo Batres, the government’s Inspector of Archaeological Monuments. Blake replied that, contrary to newspaper reports, the inspector had done nothing besides interviews, but that he’d formed a partnership with Boban. Upon his return to Mexico, Boban had begun collecting anew from a variety of archaeological sites with Batres’s assistance, and, according to Blake, Batres and Boban had attempted to sell a crystal skull to the National Museum of Mexico, saying that it had been excavated in Veracruz on Mexico’s Gulf Coast. Once the apparent fraud was discovered, the collector and inspector parted company, and Boban and his museum left Mexico abruptly for New York, where he opened yet another antiquities shop.[5]

Six months after his arrival in New York City, in December 1886, Boban put up his entire collection and library at auction on Broadway. He kept many of his most valuable objects, rather than sell low, but Tiffany and Co. purchased the “Aztec” crystal skull for one thousand dollars, considerably higher than Boban’s original asking price in France. It seems that the skull’s transit through Mexico had served Boban well. A decade later, Tiffany’s sold the skull to the British Museum, which provided a further stamp of authenticity by grouping it with legitimate Olmec, Mayan, and Aztec objects in their pre-Columbian collection.

All told, Boban may have sold as many as six large and small “Aztec” rock crystal skulls that found their way into various museum collections. For almost a century and a half they amazed museum visitors, who wondered how “primitive,” ancient people could have manufactured such carvings entirely by hand, using only stone tools. Research has demonstrated that they were not primitive, however, nor were they carved with stone tools. In a series of scientific studies of the crystal skulls in museum collection, there is ample evidence that all of those examined were created with modern, rotary lapidary tools unavailable to fifteenth-century Aztecs.

Where had they come from? It may have been that Boban was inspired by the smaller crystal skulls in his collection. Usually not larger than two inches in height, they were perhaps religious objects acquired by Boban during the years of reform, when monasteries and convents were demolished. A South American religious painting of the 18th century, in the Hispanic Society’s collection, depicts a saint holding a rosary with what appears to be a small skull attached to the crucifix. In Catholic iconography, skulls typically appear beneath the crucifix as a reference to Golgotha. The fact that all the small crystal skulls collected and sold by Boban are drilled from top to bottom would indicate that they were suspended vertically, not horizontally, like the skulls on Aztec temple racks.

The very existence of crystal skulls as a class of artifacts—one that has no known archaeological basis—is a tribute to Eugène Boban’s energies and erudition, but it also presents a cautionary tale of credulity in the romanticized skills of pre-Columbian craftsmen, turning out mystically shaped objects that just happen to be what Europeans had been making themselves.

For the researcher, however, the crystal skulls present an extra problem: although Boban sold thousands of authentic artifacts, his prominent fakes make any subsequent charge of fraudulence that much easier to believe.

Too easy, perhaps.

Boban and the Bandit

After the New York auction, which had netted over ten thousand dollars, Boban traveled by train to Washington, D.C., hoping to sell his remaining artifacts to the Smithsonian Institution. Unfortunately, his damaged reputation had preceded him. Blake’s letter about Batres and Boban included a clear warning to his colleague at the Smithsonian. “Boban has closed his museum and will remove to New York soon. Look out for him. He hopes to sell a great many things to the Smithsonian. He has some valuable antiquities, but his ownership of them gives them a suspicious character.”

Boban’s entrée to the Smithsonian was his old friend Thomas Wilson, an archaeologist and former consul in France. Wilson translated letters from Boban to William Henry Holmes offering him unsold parts of his collection. Holmes, however, had recently published an article in Science about fake pre-Columbian artifacts at the National Museum of Mexico, and he had a good eye. Despite Blake’s warnings, Holmes was very interested in purchasing Boban’s artifacts, particularly a series of Zapotec ceramics that were authentic and exceedingly rare.

The non-cultural side of the collection raised its own questions, however. Boban had offered Holmes some two-dozen human skulls, mostly Mexican, some purportedly ancient and others rather more recent, as well as a few casts of other human remains. In addition to these there were also Egyptian and “Gallo-Roman” skulls, plus one from the Congo and three from Paris. Presumably all had been part of Boban’s exhibition in his Museo Cientifico in Mexico accompanying the mummies and the crystal skull.

One skull in particular troubled Holmes: number 1389 in Boban’s catalogue, described as the “skull of Antonio Rojas, ferocious chief of Guerillas killed by a soldier of Capt. Berthelin’s Co., French Army [during the] time of Maximilian.” As it happened, Holmes had attended a popular exposition in Washington, D.C. called the Aztec Fair, produced by Benito Nichols and the Orrin brothers, Mexican circus owners. The Aztec Fair included live performers and a variety of antiquities, which photographic evidence indicate were largely nineteenth-century fakes. There were also historical sections. In one entitled “Relics of Highway Robbers in Mexico,” they exhibited the “Skull of the blood-thirsty Rojos,” [sic] shot by the Mexican troops in 1864 at Guadalajara.”

Rojas Skull, object number 243967: Skull of Antonio Rojas, who was killed in 1865 during the French intervention in Mexico. Collected by Eugène Boban and sold to the Army Medical Museum in 1887, later transferred to the Smithsonian in 1904.

The similarity between Boban’s “skull of the ferocious Guerrilla” and the Aztec Fair’s “skull of the blood-thirsty Rojos” was too problematic for Holmes to overlook. Perhaps remembering Wilson Blake’s warning to beware of the Frenchman, Holmes asked Boban about the problem of the two-headed bandit.

On April 3, 1887 the antiquarian replied, reassuring Holmes with his own discovery that ‘ancient’ skulls sold to him by the ‘Chenapan’ [rascal, scalawag] Leopoldo Batres, Mexico’s antiquities inspector, were actually modern. Having established that he knew the difference between fakes and reality, Boban explained that Rojas’s skull,

Number 1389 was given to me by a friend, Col. Tamisey, of the 60th regiment, whom I knew during the French occupation of Mexico. Since my [recent] departure from Mexico, Mr. B. Nichols [of the Aztec Fair] wanted to buy this skull from me, but found it too expensive, so asked me to sell him another. I was surprised to find the skull … exhibited in New York at the Mexican exposition and in his catalogue with the title ‘head of Rojas’ etc. I do not doubt that my friend Mr. Nichols will now be happy to rectify this little error, because now he would have us believe that Rojas, this terrible brigand, had two heads, but the original is assuredly our number 1389.

Holmes was unable to raise the money to buy the larger collection, but he introduced Boban to the curator of the Army Medical Museum, at the time located on the National Mall. The Army Medical Museum bought the skulls for $99.00, and when the cranium attributed to Rojas arrived, the Museum gave it the number 2606, replacing Boban’s original catalogue number of 1389. In 1904, the Museum transferred the collection to the Smithsonian, where Rojas’s cranium was given catalogue number 243967, superseding both previous numbers. It has been labeled and relabeled, yet retains what seems to be Boban’s own description, written just above the eye sockets:

Mexique – Rojas – Chef de Guerillas – tué par un soldat, cie. du capitain Berthelin du 81e.

The case was hardly closed, however. Sometime during the first half of the twentieth century, a member of the Smithsonian’s Anthropology staff examined the cranium and annotated the catalogue card with the information that the skull was that of a femaleapproximately thirty to forty years of age. When discovered, this surprising notation, along with the Holmes/Boban correspondence and the Aztec Fair catalogue description—not to mention Boban’s exploded “ancient Aztec” crystal skulls—cast renewed doubts on his Mexican skull dealings. Was this in fact the real Rojas skull, or was it also a fake? If it wasn’t a fake, might the fierce guerilla have been small enough for someone to identify his cranium as that of a woman?

The first matter at hand was to determine the historical facts about Antonio Rojas, and if possible, whether the facts could help discern whether or not this cranium belonged to him, and how he had become a war trophy.

The bandit or guerilla fighter, Antonio Rojas was, by most accounts a bloodthirsty, illiterate warlord, who routinely shot prisoners, as many as several hundred at a time, and torched entire towns for no apparent reason. He rode with a secretary, don Pedro Leos, who was at least as cruel and vengeful as Rojas, and whose job it was to read Rojas documents, legal and otherwise. According to a contemporary journalist, Ireneo Paz, General Rojas signed papers and official documents with an insignia intended to strike terror in the heart of his letters’ recipients: a skull, appropriately enough.

Rojas and his band of men, the Galeanos, terrorized locals in the state of Jalisco in the late 1850s and early 1860s during the War of Reform. After the French invasion of 1863, however, when President Juarez called upon all Mexicans to resist the invaders, only Antonio Rojas—“of all the chiefs, who we invited to join our grand combined forces”—responded. “Unfortunately,” added Ireneo Paz, the journalist. Paz fought alongside Rojas and was horrified at nearly every turn. At one point Rojas and his men were headquartered in a town called Zapotlan, when a stagecoach arrived from Guadalajara, the capital of the state. The general, who was suffering from a recent painful wound, became annoyed at the noisy coach’s racket. He ordered it burned, along with the passengers, coachman, and all it contained. “Those of us present had to proceed with caution, trying to cajole this furious crazy man, to dissuade him from committing such a barbarity,” Paz remembered.

First they managed to save the mail by convincing Rojas of the strategic advantages they would obtain from reading it. Then they were able to suspend the execution of the passengers, as they would be able to give news about the emplacements of the enemy. Finally they “managed to remove the death penalty from the horses, saying they could serve in the cavalry… We had to resign ourselves to watching the stagecoach in flames in the middle of the plaza. The unfortunate coachman was shot.”

Rojas was extremely effective against French forces, however, and consequently became a target for a French captain not unlike himself—the counter-guerrilla fighter Alfredo Berthelin. Berthelin was, if possible, worse than Rojas. “The Frenchman was a bloodthirsty racist, a tiger in victory,” writes the historian Paul Vanderwood. “He killed perhaps five hundred Mexicans in Colima and Jalisco.”

The showdown between the two men was violent and bloody. On January 28, 1865, Captain Berthelin, with fifty dragoons, surprised Rojas at Potrerillos. Rojas had five hundred cavalry and three hundred infantry, but was betrayed by Diego Barrientos, a member of his own Galeanos. Barrientos had joined the Galeanos to avenge his sister, who had been raped by Rojas. Barrientos’s older brother had attempted to defend their sister, when Leos, Rojas’s secretary, gouged out his eyes! Diego Barrientos finally avenged his siblings by shooting Rojas in the back, while the general and his men attempted to hold off the French attack. Fifty or sixty men died in the skirmish, Rojas and Barrientos among them.

Despite Rojas’s career as a bandit and terrorist, the lens of history wielded by his Mexican comrades gave him a heroic end. As Ireneo Paz wrote:

This extraordinary man who fought so hard for the republican institutions, surely without understanding them, letting more human blood than all the tyrants of the world, this man who was the terror of the towns and the families of Jalisco; this man who should have died hundreds of times on the gallows, perished gloriously firing his rifle against the invaders.”

V. Rojas’s Skull

So Antonio Rojas became a figure of legend—but had he become a war trophy and museum specimen?

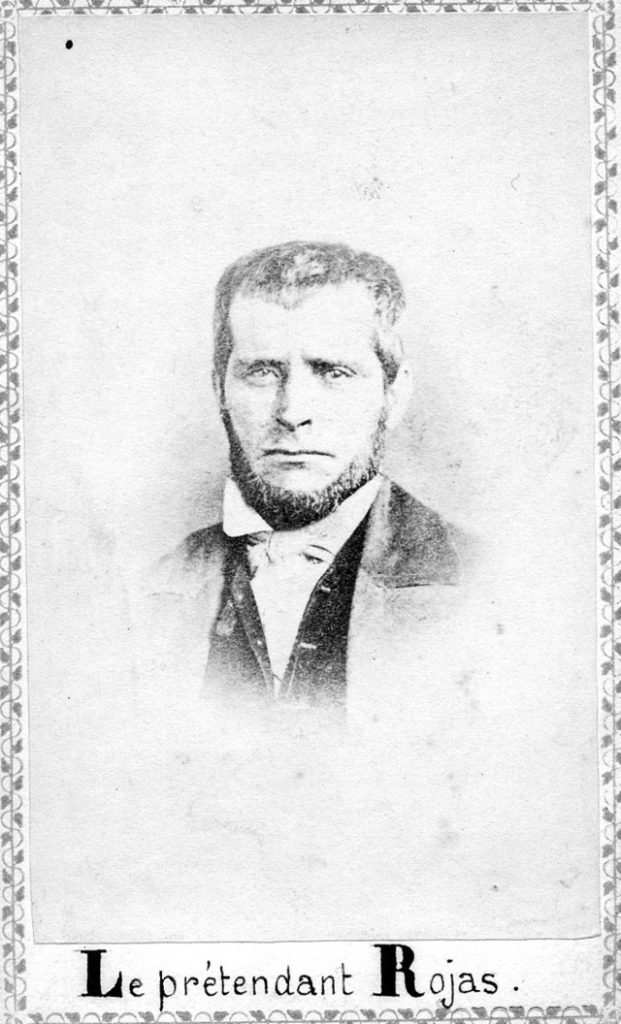

An important piece of evidence regarding the identity and authenticity of Boban’s Rojas cranium was serendipitously discovered on the Internet, when a photograph of Antonio Rojas was listed for sale. The photograph was one of ninety-four cartes-de-visite (calling card) images kept in a leather-bound album. Patented by French photographer André Disdéri in 1854, Cartes de visites were very popular in the 1850s and 1860s, when Rojas was active. The album for sale on the website was filled with images taken during the French intervention, including portraits of Benito Juarez, the many members of his cabinet, Maximilian and his court, French generals and Mexican allies, as well as Mexican generals and individuals involved in the resistance. The album was acquired from a family in Toulouse, France, whose ancestor may have been a soldier in the French army. Most of the photographs had already been sold; the Rojas image was one of the few remaining.

This photograph not only provided an image of Rojas, it also gave some detail of his facial physiognomy that could be compared to the Smithsonian’s cranium. Today, photographs are routinely used for facial recognition in security and in forensic anthropology. An individual’s identification is sometimes supported by the comparison of photographs of the live individual to the skull of the deceased. Superimposing the photographic reference over the skull can show whether the facial features and cranial vault “match.”

Using the Siemans Somotom CT scanner in the Smithsonian’s Department of Anthropology, a 3-dimensional surface rendering was made of the Rojas cranium. This surface-rendered image was then taken to the Forensic Imaging Section at the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, where forensic artist Joe Mullins superimposed the 3-D cranial image over the photograph of Rojas.

To further assess the match to the photograph, Mullins used Free-Form layering software to virtually reconstruct the face. Eyes were placed back in orbits; nasal shape was estimated by the shape of the bony nasal aperture; eyebrows were located along orbital ridges, mouth edges and forehead; and facial “tissue” was applied using standards derived from the study of living and dead individuals for skin and muscle tissue thicknesses.

As can be seen in the figures above, the photograph of Rojas and the placement of the various features of the face on the skull are suggestively close. The missing mandible makes a more accurate estimation of overall facial shape and size comparisons difficult, but the forehead, eye placement, nose alignment and mouth/tooth alignment are entirely consistent with a match.

In visual assessment of the photograph of Antonio Rojas, his facial features seem neither very coarse nor ponderous, nor does the face’s size appear large (though there are no external references to confirm this supposition). Visual assessment of the cranium conforms to the somewhat delicate features of Rojas’s face, his high forehead, small cheekbones and small-sized vault. Visual assessment of the shape of the forehead and forwardness of the cheekbones are indicative of populations of Mexico and Central America. Craniometric analysis of the cranium using ForDisc 3 discriminant analysis supports the visual assessment of an individual with indigenous admixture. This analysis places this individual in the population samples of Guatemalans or other Hispanic populations with Mexican and Central American indigenous ancestry.

From the above results, it is reasonable to assume that the human cranium sold to the Army Medical Museum by Eugène Boban in 1887 is at least a cranium of an individual from Central American populations and is quite consistent with the photograph of Antonio Rojas. With some certainty then, this is the cranium of General Antonio Rojas, killed on January 28, 1865, by one of his own men in a skirmish with French forces led by Captain Berthelin. The Smithsonian’s earlier identification of the skull as female is likely a result of the skull’s size, which, while small, is within lower statistical range of a nineteenth-century Mexican male. The depiction above of Rojas riding his horse is lacking scale, but suggests that the bandit chief may have been a diminutive demon. Despite the problematic history of Boban’s skull collections and sales, the warnings of Wilson Wilberforce Blake and the misgivings of William Henry Holmes, Rojas’s skull appears to be authentic, and we can only trust that Boban told the truth about how and where he got it.

Whether or not that changes Boban’s larger story is another matter. The self-taught amateur archaeologist understood a great deal about Mexican history and pre-history, but he was also a businessman whose flair for a dramatic story enhanced the value of his wares. He had purchased the religious paintings, statuary and other items from demolished churches, and so would certainly have known the smaller rock crystal skulls in his possession were not ancient Aztec. Creating new and exotic identities for these Spanish Catholic religious objects, however, would bring much higher prices, especially if sold alongside much larger, and more expensive, versions. He might even have rationalized that the Spanish Catholic clergy had somehow incorporated Aztec carvings into their own iconography—and that the crystal skulls he sold did, somewhere, really exist.

So hope many today, not thinking of the darker side of his cranial prestidigitation. Boban had returned to Mexico in hopes of sharing his collection and his knowledge with the Mexican people, but also for more mercenary reasons. He named his institute the Museo Científico perhaps to curry favor with the ruling elite, the Científicos, and their Inspector of Monuments, Leopoldo Batres, who gave Boban renewed access to Mexico’s archaeological riches. When Boban fled Mexico for New York, it was with numerous pre-Columbian artifacts that he had acquired from archaeological sites under Batres’s control, presumably with the complicity of the inspector. He also carried the contents of graves from throughout the country, including that of a fierce bandit who had fought Boban’s French countryman and now resides in a Smithsonian storage unit in Maryland.

Boban, by contrast, is gone, and his legacy as a self-taught scholar, the gatherer of a number of still important collections of artifacts, books and manuscripts from Mexico is sometimes clouded by his truth-stretching. After he sold his Mexican skulls to the Army Medical Museum, he received news that his aunt, Henriette Duvergé, who had taken charge of his Paris shop, had died. He returned home to resume his buying and selling and opened yet another establishment. In 1888, within a few months of his return, he sold his entire Mexican archaeological collection and what was left of his library, to Eugène Goupil, a wealthy industrialist, who had been born in Mexico. Boban would become Goupil’s curator, and assisted him in acquiring the most important collection of Mexican pictorial manuscripts in the world. Goupil published a sumptuous three-volume work on the manuscripts; the author of this catalogue raisonne was Eugène Boban. It was his crowning achievement and remains an important source to this day. The antiquarian married for a third time in 1895, and continued selling artifacts until his death in 1908. He was buried in Montparnasse cemetery, but over time the plot was not maintained, presumably because he left no heirs.

His remains were eventually removed to a nearby ossuary.

Appendix

Notes

- I am indebted to the Hispanic Society of America in New York for allowing me to study and reproduce items from the manuscript collection of Eugène Boban. [JMW]

- The publications may have been advertisements for the sale of the artifacts, but the objects highlighted were nonetheless authentic and accurately described.

- “Dans la même salle se trouvent, à l’état de spécimens et non au complet, les collections si remarquables de M. Pinart… On voit aussi une représentation de crâne humain en cristal de roche attribué à l’art mexicain: cette pièce provient de la collection Boban acquise par M. Pinart. Mais l’authenticité en paraît douteuse.”

- The mummies were purchased from Jesús Sánchez of the National Museum of Mexico where they had been kept since their discovery following the demolition of the monastery of Santo Domingo during Juarez’s reforms. Rather than victims of the Inquisition, they were more likely Dominicans who had been buried in the monastery. Eugène Boban, Catalogue of the extensive archaeological of Monsieur Eugène Boban (New York: Ed. Frossard and Charles Sotheran; Geo. A. Leavitt & Co., 1886), 34. I am very much indebted to Pascal Riviale, for introducing me to Boban’s correspondence in the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris, and also for bringing this photograph to my attention.

- Boban had met Batres in Paris in 1881 and because of their shared interest in pre-Columbian Mexico, they had developed a collegial relationship. It seems clear as well that Boban counted on the inspector’s government connections to further his renewed enterprises in Mexico.

Bibliography

- Archives of Musées d’Angers, Boban accession.

- Archivo General de la Nación, México, Ramo Movimiento Marítima.

- Armelle Le Goff and Nadia Prévost-Urkidi, Homme De Guerre, Homme de Science? Le Colonel Doutrelaine Au Mexique. (Paris: Editions du Comité des travaux historiques et Scientifiques, 2011).

- Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Département des manuscrits occidentaux, n.a.f. 21477; item 167.

- Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits occidentaux, n.a.f. 21478, item 169.

- Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits occidentaux, n.a.f. 21476.

- D. Mariano Galvan, Coleccion de las Efemerides publicadas en el Calendario Del Mas Antiguo Galvan desde su fundacion hasta el Año de 1987 (Mexico: Antigua Libreria de Murguia, S. A., 1987), p. 146.

- Eugène Boban, Museo Científico (Mexico: ed. Vanegas, 1885), p. 4.

- Eugenio Maillefert, Directorio del Comercio del Imperio Mexicano para el año de 1867 (Mexico: Instituto Dr. José María Luis Mora, 1862 [facsimile edition, 1992]), p. 221.

- Guillermo Tovar de Teresa, La Ciudad de los Palacios: crónica de un patrimonio perdido, vol. 1 (Mexico: Fundación Cultural Televisa, A.C., 1992), p. 14.

- Hispanic Society of America, Box 2240, Antiquites Mexicaines.

- Ireneo Paz, Algunas Campañas (México: El Colegio Nacional, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1997), p. 75.

- Ireneo Paz, Leyendas Historicas; Antonio Rojas. (México: Segunda Serie, Leyenda Primera. Imp., Lit. y Encuadernacion de Ireneo Paz, 1895), p. 38.

- Jane Walsh, “Crystal Skulls and Other Problems,” Exhibiting Dilemmas; Issues of Representation at the Smithsonian. Edited by Amy Henderson & Adrienne Kaeppler (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997).

- Jane MacLaren Walsh, “Legend of the Crystal Skulls,” Archaeology (Vol. 61, Number 3, 2008), 36-41.

- Jonathan Kandell, La Capital–The Biography of Mexico City (New York: Random House, 1988), p. 334.

- La Revue scientifique, (Paris: 1878, premier semester), p. 735.

- Margaret Sax, J. M. Walsh, I.C. Freestone, A.H. Rankin, N.D., Meeks, “The origin of two purportedly pre-Columbian Mexican quartz crystal skulls,” The Journal of Archaeological Science (Elsevier, 2008), 2751-2760.

- Margaret Sax & Nigel Meeks, “The manufacture of a small crystal skull purported to be from ancient Mexico,” The British Museum Technical Research Bulletin (London: Vol. 3, 2009), 47-55.

- Paul Vanderwood, Disorder and Progress: Bandits, Police, and Mexican Development (Wilmington: SR Books, 1992), p. 6.

- S. D. Ousley, and R.L. Jantz, FORDISC 3.0: Personal Computer Forensic Discriminant Functions. University of Tennessee, 2005.

- Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accessions USNM 17619.

- Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 7084, William Henry Holmes papers 1870-1931.

- Thomas Calligaro, Yvan Coquinot, Ina Reiche, Jacques Castaing, Joseph Salomon, Gerard Ferrand, and Yves Le Fur, “Dating study of two rock crystal carvings by surface microtopography and by ion beam analyses of hydrogen,” Applied Physics A: Materials Science & Processing 94 no. 4 (2009), 871–878.

- W. F. Bullock, Across Mexico in 1864-1865 (London: MacMillan and Co, 1866), p. 83.

Originally published by The Appendix 1:2 (April 2013) under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.