By Drew DeSilver

Senior Writer/Editor

Pew Research Center

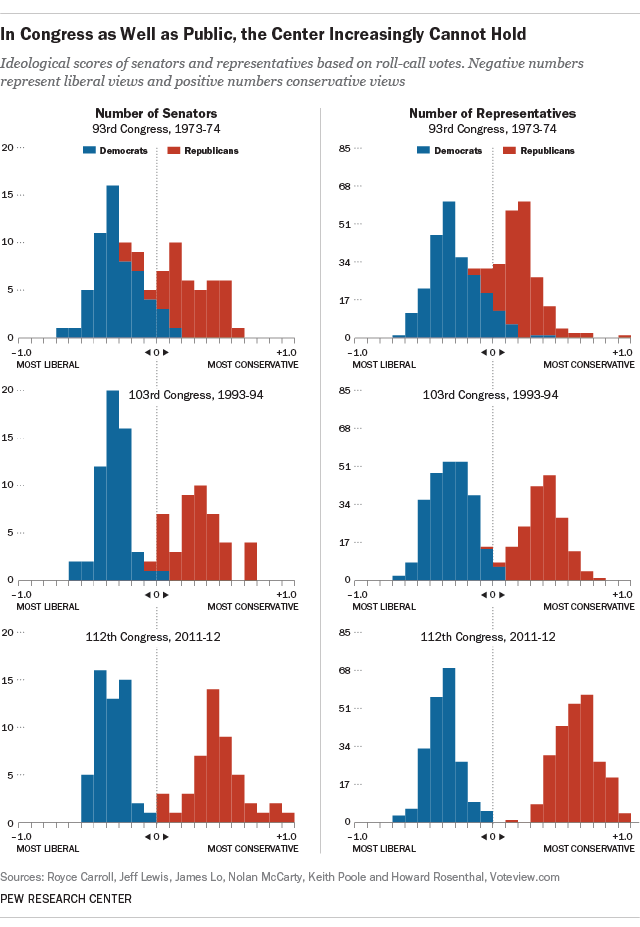

You don’t have to look hard to see evidence of political polarization — just watch cable news, listen to talk radio or follow social-media debates. Indeed, a new Pew Research Center report finds that Americans are more ideologically polarized today than they’ve been in at least two decades. Their representatives in Congress are divided too, and have been pulling apart since the days of M*A*S*H and Billy Beer.

With Democrats and Republicans more ideologically separated than ever before, compromises have become scarcer and more difficult to achieve, contributing to the current Congress’ inability to get much of consequence done. But going beyond anecdotal evidence to examine congressional polarization more rigorously can be tricky.

Fortunately, political scientists Keith Poole and Howard Rosenthal have developed a widely accepted metric, DW-NOMINATE, that places every senator and representative on the same set of ideological scales. Using their data, it’s clear that the congressional parties, after decades of relatively little polarization, began pulling apart in the mid-1970s. Today, they say, “Congress is now more polarized than at any time since the end of Reconstruction.”

The researchers aggregated roll call votes to locate each member of Congress, from 1789 to the present day, on a two-dimensional grid. One dimension represents the traditional liberal-conservative spectrum; the second picks up regional issue differences, such as the split between Northern and Southern Democrats over civil rights in the 1950s and 1960s. As Poole and Rosenthal note, those formerly significant regional distinctions have declined in importance — or, more precisely, merged into the overall liberal-conservative divide: “Voting in Congress is now almost purely one-dimensional — [political ideology] accounts for about 93 percent of roll call voting choices in the 113th House and Senate.” So we used just the ideological dimension in our analysis.

We took the vote scores for every senator and representative in five Congresses, one in each of the past five decades, and ordered them from most liberal (scores of -1 to 0) to most conservative (0 to +1). Then we sorted them by party to see how much overlap — if any — there was between Democrats and Republicans (for simplicity, we excluded the handful of independents).

In 1973-74, there was in fact substantial overlap. In the House, 240 members scored in between the most conservative Democrat (John Rarick of Louisiana) and the most liberal Republican (Charles Whalen of Ohio); 29 senators scored between New Jersey’s Clifford Case (most liberal Republican) and James Allen of Alabama (most conservative Democrat).

A decade later, though, that had already begun to change. By 1983-84, only 10 senators and 66 representatives (except for Rep. Larry McDonald (D-Ga.), who scored more conservative than every single Republican) fell between their chambers’ most liberal Republican and most conservative Democrat. By 1993-94, the overlap between the most conservative Democrat and the most liberal Republican had fallen to nine House members and three senators. By 2011-12 there was no overlap at all in either chamber.

What’s happened? In large part, the disappearance of moderate-to-liberal Republicans (mainly in the Northeast) and conservative Democrats (primarily in the South). Since the 1970s, the congressional parties have sorted themselves both ideologically and geographically. The combined House delegation of the six New England states, for instance, went from 15 Democrats and 10 Republicans in 1973-74 to 20 Democrats and two Republicans in 2011-12. In the South the combined House delegation essentially switched positions: from 91 Democrats and 42 Republicans in 1973-74 to 107 Republicans and 47 Democrats in 2011-12.

Political scientists debate whether polarization in Congress preceded or followed polarization among the wider public, and our data (which begins in 1994) won’t resolve that. One thing is clear, though: When a polarized Congress represents a polarized public, not much gets done legislatively. Through the end of May, the current Congress had enacted 89 pieces of substantive legislation (based on the methodology we’ve employed in prior Fact Tank posts) since it opened in January 2013. A decade ago, at the equivalent point in its term, Congress had enacted almost twice as many substantive laws.

Historically, compromise has been key to getting legislation passed. But polarized senators and representatives — reluctant to compromise with the other side to start with — won’t get much pressure from the partisans back in their home states. According to our study, while 56% of Americans say they prefer politicians who are willing to compromise, in practice both across-the-board conservatives and across-the-board liberals say the end result of compromise should be that their side gets more of what it wants.

Originally published by Pew Research Center, 06.12.2014, reprinted with permission for non-commercial, educational purposes.