Culture and prejudice played profound roles in generating violence.

By Dr. Wayne E. Lee

Bruce W. Carney Distinguished Professor of History

University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

Introduction

Augustus Caesar would say, that he wondered that Alexander feared he should want work, having no more worlds to conquer: as if it were not as hard a matter to keep as to conquer.

Francis Bacon1

[The first emperor of China] failed to rule with humanity and righteousness and did not realize that the power to attack and the power to retain what one has thereby won, are not the same … Insuring peace and stability in the lands one has annexed calls for a respect for authority. Hence I say that seizing and guarding what you have seized, do not depend upon the same techniques.

The Grand Historian Sima Qian, critiquing China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huangdi2

Since the old days the Tatar have fought our fathers and grandfathers. Now to get revenge for all the defeats, to get satisfaction for the deaths of our grandfathers and fathers, we’ll kill every Tatar man taller than the linch-pin on the wheel of a cart. We’ll kill them until they’re destroyed as a tribe. The rest we’ll make into slaves and disperse them among us.

Chinggis Khan, as recorded in the Secret History3

It was not plunder they [the Cherokees] wanted from them [the Creeks] but to go to war with them and cut them of[f ] [kill them].

George Chicken, reporting on Cherokee motivations in 17154

Large-scale coordinated violence has nearly always sought to rearrange political authority; violence in self-defence is not an exception to this statement, as it merely seeks to maintain the status quo.5 The post-victory process of rearranging authority and its subsequent maintenance, however, is less well studied than the immediate means of achieving that victory. In part, this is because military history has traditionally focused on the narratives and variables of campaigns and battles, while political history tends to focus on long-term state formation through the lens of institutional development. As a result, analyses of the key role of force in the complex dynamic of consolidating and maintaining conquest after victory have fallen between the cracks.6 Furthermore, historians in general have focused on these dynamics within and among traditional sedentary states, eliding wide swathes of the human experi-ence outside that social formation. Indeed, even the word ‘conquest’ is not quite right, as it implies some form of territorial capture or control. As we will see, not all war was about controlling or occupying territory.7

The theoretical model presented here, therefore, seeks to transcend states. It posits that victors in the pre-industrial world secured the long-term benefits of military success through a combination of four ‘pillars’: legitimacy, sanctity, bureaucracy, and the deployment of force in a security or ‘latent’ mode. The way victors deployed the last pillar, latent force, was heavily shaped by logistical considerations, which in turn reflected the fundamentals of the victor’s subsistence system. Rather than simply comparing different states, or even comparing ‘barbarians’ with more settled polities, this chapter compares early modern societies according to their different systems of subsistence: agricultural states, nomadic pastoral clans on the Eurasian steppe, and Native American polities in the North American woodlands during the historic era.8 These are used to analyse different forms of ‘conquest’ – the ability to secure long-term benefits of military success – thereby highlighting the structural relationship between logistics and the expected rewards of conquest. The chapter focuses first on conflict within each of these subsistence niches. Over time, patterns of conquest within each niche generated normative definitions of victory and associated expectations about the fate of defeated populations. When different systems clashed – for example, when the steppe invaded the sown or when the forces of a state marched into the North American woods – the resulting mismatch of expectations about the meaning of victory changed not only the violence of war, but also the violence of post-war consolidation.

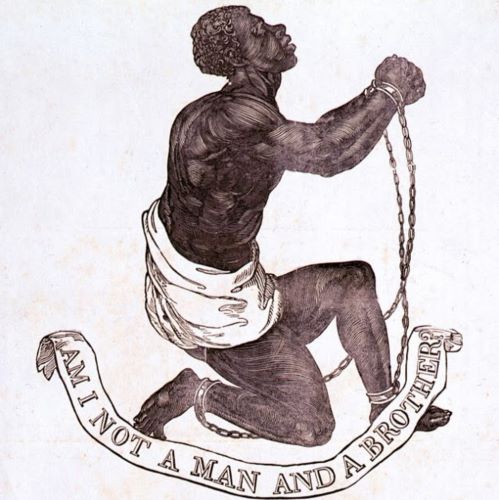

Moving beyond a focus on settled states as the norm and instead systematically comparing a fuller range of sociopolitical formations can move us beyond simplistic assumptions about the violence of ‘primitives’, ‘savages’, ‘barbarians’, or even intruding ‘colonists’. Culture and prejudice surely played profound roles in generating violence, including violence beyond what was considered normal.9 This approach also lessens our dependence on contemporary representations and accounts of violence and allows us to investigate the relationship between structure and violence: the ways in which fundamental structural conflicts were embedded in different societies’ expectations of resource extraction in the wake of so-called victory.

Hierarchical Agricultural States

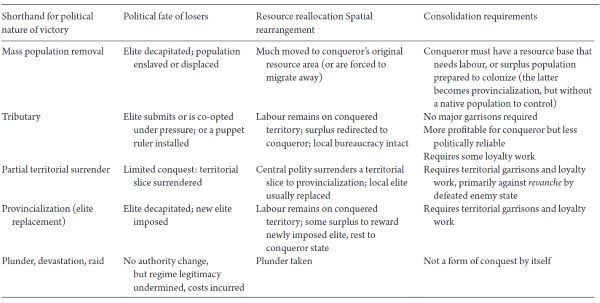

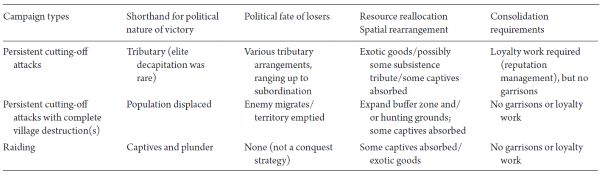

In the states of the pre-industrial world, one can discern three basic types of conquest wielded against other states, summarized in Table 1 (along with two forms of non-conquest outcomes):

This simple typology is messier in reality of course. Methods were used in varying combinations, depending on the victorious state’s calculation of risks and rewards. Furthermore, complete conquests were relatively rare. More common outcomes are reflected in the table by the two non-conquest types: one in which the losing side surrendered a slice of territory to the victor to bring an end to an expensive or increasingly dangerous conflict, and the other when there was little thought of outright conquest and instead the combatants sought more short-term plunder or merely to exert political pressure through destruction. Finally, these conquest methods also often occurred in succession. A losing or weaker state might submit, thus becoming a tributary vassal or client, but then later rebel, leading to a more complete conquest and provincialization – a pattern common to Assyria, Egypt, China, Rome, and many other expansive states in the pre-industrial world. The larger point is that each of these methods of consolidating conquest was designed to capture resources from the territory and labour of the defeated state, largely for the benefit of the elite in the victorious state.

The elites of most pre-industrial states reaped the rewards of conquest person-ally, but rulers also ‘reinvested’ in their military capacity, using conquest to help acquire more force. But here we must distinguish between ‘force’ and ‘power’.10 Power in this sense was the ability to rule without the resort to force. When behavioural assumptions and cultural norms of deference allowed for the peaceful collection of taxes (for example), a ruler’s fundamental power was greater than if he or she had to rely on force for that collection.

Consolidating power over conquered populations rested on four pillars. These pillars are not confined to states, but the state provides us with a familiar framework within which to consider them and we will turn to their non-state manifestations later. The four pillars are legitimacy, sanctity, bureaucracy, and latent force.11 Power – rule without resort to violence – ultimately relied on legitimacy, and there were many frameworks for establishing this: the claim of blood descent, the imprimatur of an election, a cultural belief in victory as a sign from the divine, or even simply a reputation for generosity to allies and kin in the aftermath of victory. All were mechanisms for asserting the legitimacy of rule. Very frequently, however, legitimacy was tied to a claim of sanctity. A claim of access to the divine was so significant and so common that we must consider it separately from legitimacy. Bureaucracy institutionalized the exercise of power without the resort to violence. It was more mechanistic than the cultural norms required for legitimacy or sanctity, but its regularized systems of extraction, especially when modulated by law, depersonalized the process. Bureaucracy distanced the ruler or the elite from the resentment of the taxed and thus sustained the broader legitimacy of rule.

In the long term, legitimacy, sanctity, and bureaucracy are cheaper and more efficient pillars of rule than force, but establishing any of them among a newly defeated population represented a generational challenge. Creating a legitimate heritable or transferable dynasty beyond the immediate ‘rights of the victor’ required what we will call here more generally ‘loyalty work’. Establishing claims to a divine connection, for example, might require generations of cultivation. Fortunately for many new conquerors, bureaucracy, unlike sanctity or legitimacy, often proved somewhat easier to transfer to the victor.

Even more than bureaucracy, however, the readiest pillar for consolidating control in the immediate wake of state territorial conquest was the management and distribution of some form of latent force. Military forces, even if no longer actively fighting, provided a visible guarantee against continued resistance or future rebellion. In general, the precise ways that latent force was composed, used, and distributed depended on two key factors: the specific type of conquest (tributary, provincialization, and so on) and the military logistical system, which was in turn derived from the normal demographic operating environment of the conquering society. It is this latter tripartite relationship (demographic space – military logistics – latent force management) that primarily concerns us here.

The logistics supporting an agricultural state’s military on campaign differed from those required for latent force. Campaign logistics depended primarily on the roads (rivers in some cases) and the food generated by the local organic economy: armies moved on locally built roads and ate locally produced food. In low-density, resource-scarce environments (deserts, mountains, and so on), wagons carrying supplies assumed greater importance, and sometimes roads had to be built as part of the campaign.

Latent force logistics, however, presents a somewhat different problem, visible in outline in the ‘consolidation requirements’ column of Table 1. We can dispose of the first two relatively quickly, because mass displacement and tributary submission typically avoided latent force costs. An enslaved population brought back to labour in the home territory, or sent to another province of the empire, required relatively little latent force (except possibly to escort them along the march). Such a population, beaten down, often dispersed, in an unfamiliar territory, and probably deprived of many of its adult men by defeat, was an unlikely immediate source of rebellion. Rather than outright force, enslaved populations were managed more by a rearrangement of the bureaucracy to provide slave codes and relatively cheap policing.

The next cheapest option was some form of submission followed by a tributary relationship. In this case, land and labour came together, almost entirely without administrative cost to the victor. The losing state continued to operate its own systems of collecting surplus and provided its own internal and external security, only now the tributary state transmitted part of its surplus to the victor as tribute. Depending on the exact nature and terms of the submission, the victor might have to fund a puppet ruler, or even locate a small garrison in the loser’s territory, but compared to provincialization the logistical requirements were tiny.

Provincialization, however, either of a surrendered slice of territory or of the entire territory of a defeated state, put heavier demands on latent force. The usual requirement was some form of distributed garrisons around the defeated territory. There were other forms of latent force – such as the court as travelling armed camp, in which the king moved around his territory accompanied by the army, imposing costs on his local hosts, reminding them of his power, and keeping the army supplied by moving – but garrisons were the more common method among agricultural states. The number and location of garrisons varied with geography and population distribution, but population control and the enforcement of surplus collection required a wide distribution of force. Like troops on campaign, those troops had to eat and move. In densely settled and well-developed areas, it was a relatively simple matter to put such garrisons into regional market towns and the loser’s capital, where roads came together and to which food was already being regularly transported by the normal functioning of the economy. In many cases, however, the occupiers had to split forces into smaller garrisons, since no one region could supply sufficient food for a large army for very long, except at the great expense of transporting it. English forces in Ireland in the sixteenth century made these kinds of calculations explicit – in peacetime they dispersed garrisons around the territory to ‘bridle’ the countryside, with each garrison dependent on local food and transportation networks. The garrisons were supposed to live from the ‘cess’ of the surrounding countryside – a kind of tax-in-kind – and meanwhile, if the locals rebelled, that same produce would be for-feit to destructive raids by the garrison.12 English long-term plans in Ireland sought to build the other pillars of conquest by ‘shiring’ the Gaelic territories, imposing the English county structure, property law, and judicial systems.13

In densely populated core provinces, as the other three pillars of conquest took hold, latent force became less necessary. Frequently those forces then moved to the state’s periphery, where the local population might not be dense enough to sustain them. In such undeveloped regions the central government found itself paying for walls, roads, and for the long-distance transport of food to sustain the garrisons – one need only think of the Roman frontier and the Chinese steppe frontier, but other examples abound, not least in the Ottoman and Russian empires. Alternatively, as became common in medieval China, soldiers were required to grow their own food on the frontiers. These expensive frontier latent force requirements were only made possible by the shift to cheaper forms of legitimated bureaucratic rule in the core provinces.

In sum: the military conquest of one agricultural state by another made it possible to extract new wealth from the additional territory (or from a newly enslaved labour pool). A tributary-type conquest did not require the victor to deploy force to extract that wealth, but it was less politically stable. If the victor opted for provincialization – often the case after a rebellion – wealth extraction during the early stages of consolidation required the distribution of latent force in the form of garrisons around the new territory, typically fed by local foodstuffs moving through existing road and market networks. These relationships of demographic space to force distribution were established by the very nature of the agricultural organic economy as exploited by a hierarchical state. None of this is particularly surprising, but framing the issue in this way becomes more interesting as we turn to other demographic spaces.

Steppe Nomadic Pastoral Tribes

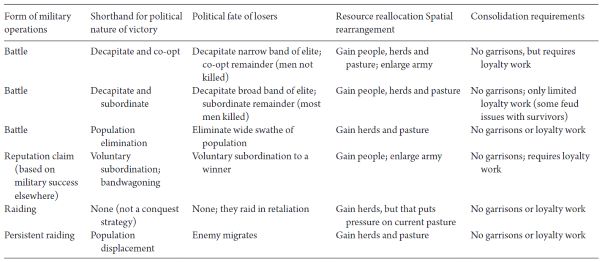

The organic economy and political structures of nomadic pastoralists differed markedly, and in that demographic space military logistics rested on very different foundations and therefore so did the possibilities and requirements of latent force. Specific locations were relatively less important as neither surplus nor political power accumulated in any one location – at least until a steppe tribal confederation achieved imperial levels of success and conquered sedentary states. In intra-tribal conflicts, however, there were few strategic shortcuts of attacking cities or key transit points for surplus goods; one had to attack the people themselves. And adding defeated people tended to be the main point of success: as Bat-Ochir Bold noted, although the chronicles ‘often relate of one tribe conquering another and taking the conquered nutug [pasture] into its possession … the basic motivation for gaining possession of nutug was to use the conquered people as potential soldiers and not as labourers’.14

In this economy, ‘conquest’ meant capturing people and their flocks, with varying fates for the defeated elites – meaning the clan leaders, their immediate male kin and their closest followers (or nöker in Mongolian). Table 2 summarizes the types of conquest, of which the first three are all simply variants of incorporating a defeated people. These differ primarily in the extremeness of how the victor treats the losers – a choice determined by the probability of successfully incorporating the adult men, and influenced by the history of their rivalry and the ambitions of the victor. The first option was by far the preferred one, since it allowed for the incorporation of a large number of the defeated men as warriors.

The final two represent the most typical form of steppe warfare, in which small-scale clan-level raids netted plunder and people, but generally lacked the decisive outcome of a major battle. Such raids would be the normal pattern of war and only infrequently would they tip any regional balance of power. However, it is important to note that it was success in these raids that could build a young leader’s reputation and lead to further and further confederation through the remaining type of conquest: voluntary subordination, or what political scientists refer to as ‘bandwagoning’ – joining the winning side.

It was through raids and the consequent gradual acquisition of loyal followers, blood brothers, and a powerful nöker that Temujin slowly and painfully rose to become the head of a massive tribal confederation that would then become an empire under his new name of Chinggis Khan. The more powerful such a leader became, the more other tribes would voluntarily sign up to his cause, hoping to reap the rewards of further success. The empire’s political fragility remained, however, and holding it together required the loyalty work embedded in the other three pillars of political consolidation.15 Legitimacy and sanctity via proof of bloodline, success in battle, and proper adherence to key rituals were central to maintaining control, but neither bureaucracy nor latent force played much of a role. Even those defeated peoples who the sources say became ‘slaves’ of the victors (bo ‘ol in Mongolian) occupied a more complex status than is usually associated with that word; they were subordinated and incorporated, but with a future that could include advancement and even elite status, meaning that latent force played little role in enforcing obedience from a enslaved class.16 Successful nomadic conquerors could and did impose rule over others; their societies could and did stratify along lines of wealth, bloodline, and position, but the mechanisms of rule differed from the territorial forms of agricultural states.17 Among other things, bureaucracy on the steppe was minimalist at best – although successful steppe conquerors of sedentary lands quickly adopted sedentary bureaucracies to serve them.18 As for latent force, the legitimacy of rule on the steppe depended on successful active force and there was little room for its use in a latent mode, except to the extent that one might consider military reputation to have acted as a kind of latent force check on rebellion.

Latent Force on the Steppe

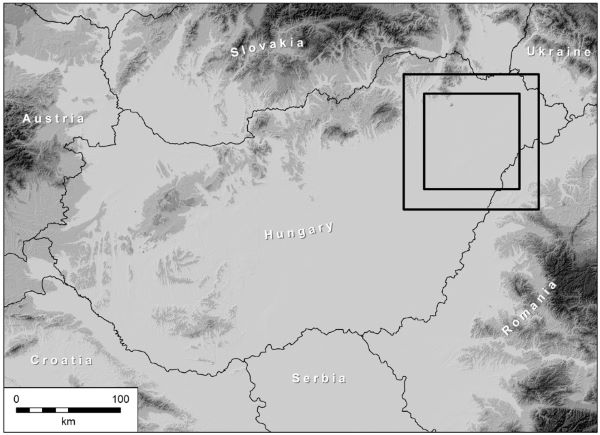

As already discussed, victors rapidly accumulated force by incorporating the defeated into their own armies. This was a fundamental component of steppe life.19 But turning nomads into something resembling a garrison-based latent force was harder to do. For one thing, garrisons could not control nomadic populations, much less extract surplus from them, since people were not tied to the land in a way that a static deployment of force could control. But even more important were the logistical obstacles to maintaining a large nomadic force in any single location. These problems boil down to the calories in a steppe warrior’s ration and the acres of grass required for a large herd of horses. To shortcut a lot of calculations (and a tremendous amount of uncertainty about pasture requirements), we can use a relatively moderate estimate that each soldier would need 208 acres of steppe pasture to sustain the bare minimum string of five horses and one sheep for a year (in stockage terms this is twenty-six ‘sheep-equivalents’).20 To convey what that means graphically, consider the annual pasture requirement for a single 10,000-man Mongolian tümen (a division) superimposed on a map of Hungary (Map 1).21

Furthermore, five horses and one sheep are an extreme minimum, which does not include breeding stock or account for any of the other realities of maintaining herds for more than a single year. This expansive requirement for pasture immediately suggests the problem with setting up territorial garrisons: steppe forces needed to keep moving or disperse. Without garrisons, the role of force in post-conquest consolidation among steppe tribes was reputational: if you rebel, we will again call up our loyal forces and defeat you. It was not preventative force; it was a retaliatory promise. This pattern of expectations showed itself most dramatically when nomadic conquerors used violence in conquered sedentary states. Having extracted the promise of submission, they then heavily punished disobedience with extreme retaliatory violence, as Chinggis Khan did to the Xi Xia empire when they began to refuse to cooperate as promised.22

Native Americans in Eastern Woodland North America

The notion of ‘conquest’ among North American indigenous peoples is harder to identify and define, in part because many anthropologists and historians long resisted the idea that Native American warfare was indeed lethal and that it often aimed to enhance one group’s power at the expense of another.23 Many scholars now recognize the pre- and post-contact role of violent resource competition in Native American society, agreeing that Native Americans, in line with much of the rest of the world, fought with deadly intent and with both individual and group interests in mind. David Silverman, for example, recently summarized Native American motivations for war as ‘the defense or expansion of territory; the seizure of captives for enslavement and adoption; the negotiation of tributary relationships between communities; the revenge of insults; the protection of kin from outside aggressors; and the plunder of enemy wealth’.24

As with our other examples, military activity and the implications for consolidating victory into some form of gain were powerfully shaped by the Native North American organic economy and their fundamental sociopolitical organization. In approaching military logistics in the demographic space of native North America, we should remember that North America was not ‘wilderness’. It was an environment substantially shaped by human activity, albeit differently from what European settlers expected.25 Clusters of associated towns had many beaten paths between them, as well as out to their fields and primary gathering areas. The forest immediately surrounding a town would have been punctuated by ‘oldfields’ – that is, abandoned farm fields left fallow and now often prime locations for nearby hunting (deer prefer to browse in meadows close to the cover of trees). In addition, paths to distant hunting grounds or for trade were clearly marked out and could stretch hundreds of miles – the so-called Warriors’ Path extending from upstate New York to the Cherokee and Catawba country in North and South Carolina is only the most famous. There were many such paths.26 Similarly, navigable waterways and the appropriate technology for traversing them and then portaging around fall lines were well known and portage paths well established.

This may not sound that far removed from agricultural states in the sense that we have villages surrounded by a network of fields and paths, but the differences were considerable. Paths in North America were designed for humans in single file. Draft animals and wagons were unknown before European contact and throughout the middle of the eighteenth century among the Native Americans of the eastern woodlands horses remained rare, especially in warfare. In addition, once away from the village cluster itself, the density of the route network would have dropped precipitously, confining military movement to remarkably predictable paths on both land and water.

In general, therefore, Native Americans had no means for bringing supplies along in their wake, although there are some accounts of laden canoes being left behind as a kind of supply cache. Evidence suggests that war parties often hunted en route, but once they were in enemy territory this was more difficult to do safely.27 As a result, when a war party arrived at an enemy town cluster at the end of a long march, they lacked the logistical means to remain there for very long. They could not conduct a protracted siege, and if they succeeded in taking a town by assault or rapid siege, they had no way to resupply their forces to remain and hold the town in the face of reinforcements from other nearby related towns (a very strong possibility given the way they were clustered). Captured Europeans who narrated their experiences frequently attested to the logistical desperation on the return march to their captors’ hometown.28 This reality not only affected how Native Americans perceived conquest, it also affected how they thought of using latent force to consolidate conquest.29

Beyond logistics, two key characteristics of Native American sociopolitical configurations related to the other pillars of rule also affected campaigning and con-quest. First was the strong pressure to avoid catastrophic losses. The relatively egalitarian and consensus-based authority structure in most historic period Native American societies meant that extreme casualties would dramatically undermine a leader’s legitimacy.30 Second, the blood revenge imperative was crucial in motivating individual warriors to join a war party and its requirements profoundly shaped the nature of their campaigning. Among other things, warriors who had assuaged its requirements might feel no compunction in returning home, regardless of the needs of the group.31 The feud’s prominence, however, has tended to obscure the extent to which many ongoing conflicts were about more than mere revenge – they were also about resources, even if only in the sense that maintaining a reputation for effectively taking revenge was key to both minimizing challenges and for consolidating ‘conquest’. Reputation management, as on the steppe, was a form of latent force.

To leap ahead into the argument, there were only two types of victory consolidation in woodland war (see Table 3). The third type shown in the table, small-scale raiding, is not a conquest strategy as such, much like the last type in Table 1. Although small-scale raiding may not have been intended to force major resource allocations (whether people, land, or other resources), it did successfully fulfil cultural mandates for blood revenge while also maintaining the group’s reputation for strength, hopefully forestalling attacks on its home territory as a result. On the other hand, persistent raiding, even on a small scale, especially raids that ‘cut off’ one or more towns, could expect over time either to force population displacement or to achieve submission leading to a tributary arrangement. Note that either result could come about from the same type of campaigning; which one occurred depended on both sides’ assessment of their relative strength. Neither of these results necessarily lends itself to traditional notions of conquest, but resources were certainly being reallocated as a result of victory. What is interesting here is the relatively low requirement for latent force to consolidate victory. Let us consider each in turn: displacement and tributary submission.

Displacement

As we have seen, a war party at the end of a long march was at the end of its logistical tether and operating within a kind of danger zone, surrounded by enemy towns in a regional cluster. Attackers tended to hit quickly and then return home. There was no logistical support – and neither was there cultural support through the blood-feud dynamic – for ‘take-and-hold’ territorial war. On the other hand, persistent attacks or a few massively successful town attacks could force a threatened people to decamp and evacuate the region. In other words, wars could be fought in order to empty space. Iroquois attacks on the Huron in the late 1640s famously forced Huron migration, leaving their territory essentially empty. These migrations have often been seen as a victim’s response, but they were just as likely to have been the victor’s objective, even in intra-Indian warfare. Such emptiness produces a wider buffer zone in which game can flourish, effectively increasing the hunting territory safely available to the victor.

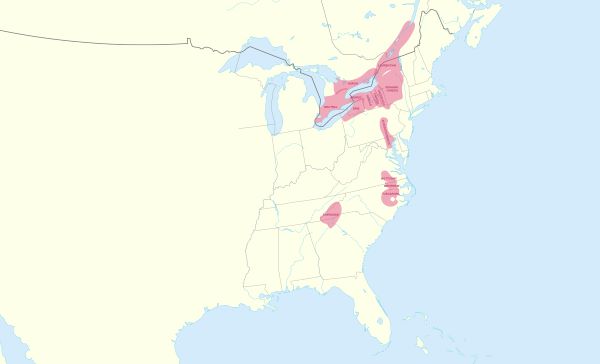

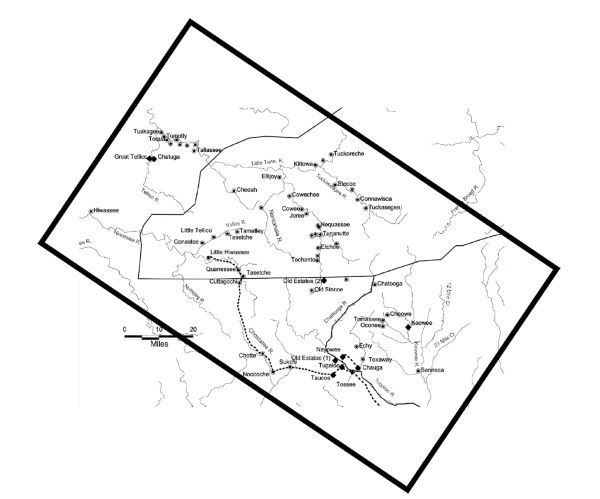

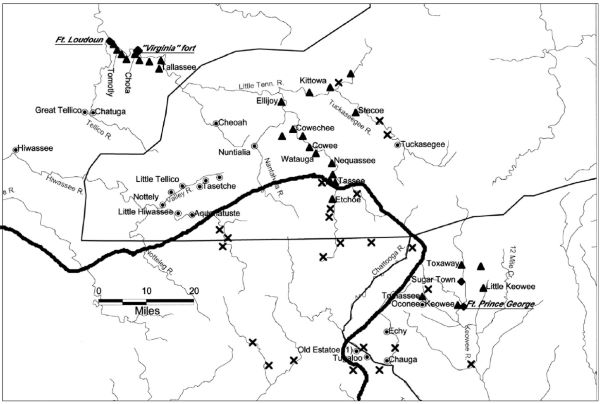

In the Creek–Cherokee War of 1715 to 1752, we can trace the impact fairly clearly. Map 2 conveys a sense of how much acreage was required to support a deer population large enough to sustain the Cherokee subsistence system, which depended on hunting in the winter.32

When compared with Map 3, which shows the depopulation or forced migration of the southern Cherokee towns during the long war, it is clear how this now vacant space represented a large accession of hunting grounds for the Creeks, as well as a deeper security buffer zone between themselves and the remaining Cherokees.33 It is rare to be able to reconstruct this kind of detailed version of territory being emptied by war, but one often finds it as an expectation among defeated peoples in the way many of them proceeded to migrate. We have already mentioned the departure of the Hurons after the Iroquois attacks in 1648 and 1649. Other defeated peoples’ migrations include the Tuscaroras, the Yamasees, the Delawares, the Shawnees/Savannahs, the Eries/Westos and more.34 Historians have often interpreted these movements as part of coalescence in the face of defeat – and so they were. But they also signified the departure of the defeated from their original home territory. Rather than submit, they departed.

This form of victory consolidation by simply emptying territory is extremely cheap. It does not require any deployment of latent force, nor is any loyalty work required to prop up the other three pillars of rule (legitimacy, sanctity, or bureaucracy). And in terms of reputation management, which we have called a form of latent force, the campaigns themselves functioned to shore up that reputation.

Tributary

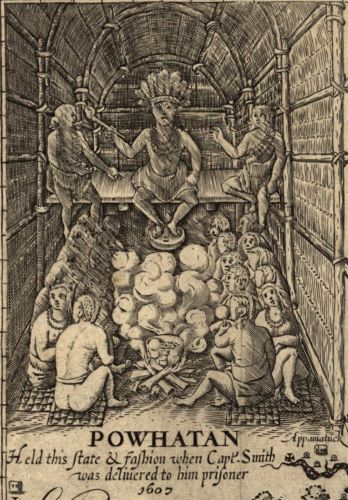

For all the same logistical and sociopolitical reasons, warfare conducted to impose a tributary status also lacked the means to deploy latent force. Even during the increasingly territorial and authoritarian rule of Powhatan over much of the Chesapeake Bay, there is no evidence for garrison distribution. Powhatan’s wars instead used both types discussed here: he warred to empty territory in fear of threats to his authority and he warred to establish tributary relationships over other towns. Tribute, however, seems to have been his primary goal: that is, to force a group to submit to his authority at least to the point that they regularly sent him tribute in material form – both exotic goods and subsistence.35 Having imposed a tributary relationship on a submitted population, however, meant that the chief had to put a higher premium both on reputation management and on other forms of cultural work to control them. Powhatan’s control seems to have been relatively authoritarian, but the other well-known example, that between the Iroquois Confederacy and their defeated tributary ‘subordinate’ peoples, suggests a much milder form of control. Francis Jennings’s examination of the relationship between the Iroquois and the Delaware conveys the complexity of the problem. The Delawares briefly admitted an Iroquois chief to live among them and they appear to have surrendered control of some of their foreign policy to the Iroquois. But they retained almost complete autonomy in their relations with Pennsylvania and control over their own territory – although the Iroquois would pressure them to sell to Pennsylvania in 1737 (The Walking Purchase). Indicative of the many shades of grey in the varieties of submission, however, was the fate of the Susquehannocks, whom the Iroquois more completely removed from their original home territory and absorbed into their central population – not as slaves or subordinates, but as new kin.36

Within all these variations of submission, however, the need persisted to do cultural work in the submitted population, either to fully embed them as new kin or to persuade them of the finality of their submission. Bureaucracy as we understand it did not figure in that process, but issues of legitimacy and sanctity did play a role. We know, for example, that central to establishing legitimacy for the incorporation of individual captives was the mechanism of assigning kinship. In the mourning war tradition of the Iroquois peoples and among many other groups, individual captives were assigned specific familial roles, often replacing recently deceased family members.37 Such a kinship claim also probably played a role in maintaining the subordination of whole populations, in the way that the Delawares, for example, were called ‘nephews’ after their submission. With respect to latent force, one sees similar cultural mechanisms at work in reputation management rather than a physical gar-rison or other distribution of force. One wonders, for example, how far the much-discussed habit of the Iroquois of referring to the Delawares as ‘women’, and thus unable to make war, was a rhetorical means of enforcing subordination and enhancing Iroquois martiality.38 Or whether Powhatan’s mock battle, witnessed and described by John Smith, was something regularly conducted to persuade assorted audiences of his overwhelming power?39

The Implications for the Violence of Conquest

Several implications emerge from this comparative discussion of the role of subsistence systems and logistics in defining the nature of conquest and consolidation. The most significant for this volume on violence were the consequences when war occurred outside of the symmetrical pairs presented here. Each example explored thus far has been deliberately symmetrical: states against states, steppe tribes versus steppe tribes, and the intertribal conflicts in Native North America. Patterns of conflict repeated over time within those pairs created not just a material reality but also an ideological framework through which participants understood the function of war and anticipated its rewards. War with a people outside that framework generated both material and ideological challenges.

For example, the normal steppe nomad’s expectation of absorbing defeated nomads with a similar lifestyle meant that controlling peasants had no initial appeal for them. This attitude generated the famous moments in which nomad victors considered converting conquered farmland into pasture (which of course would have left the peasants to starve or move).40 This was partly logistical, since they were well aware that a landscape of grain fields or rice paddies could not sustain their horses. It was also a normal initial response for a steppe tribe that had not yet imagined becoming an expansive empire. Their more usual raids on peasant communities along the steppe frontier could not lead to snowballing force; the standard forms of absorbing defeated tribes simply did not apply to those who were not also horsemen.41 The result tended to be a higher level of violence meted out to the sedentary population. For example, in an odd reversal of the usual steppe decapitation strategy, ‘when the Turk-Khazars attacked Caucasian Albaniain 628 as allies of Byzantium, the Qağan allowed those “nobles and leaders” who surrendered “to live and serve me”. As for the others, all males over fifteen years of age were to be killed and the women and children enslaved.’42 In this instance, the Qağan seems to have adopted the nomadic concept of folding defeated elites into his extended warrior household (or nöker) as part of the conquest of a sedentary state, but he found no use for the majority of the defeated male population. This mismatch of expectations of conquest may have led to wider swathes of adult men being killed than in similar defeats of nomadic peoples. When a steppe people became imperial conquerors they learned to modify their attitudes towards the conquered populations, building systems of bureaucratic rule and distributing garrisons composed of their defeated sedentary enemies’ forces. But in general, the endemic conflicts between sedentary and nomadic peoples produced extraordinary levels of violence – partly due to a sense of cultural superiority on both sides, but also because of their very different senses of what victory was supposed to bring.

Likewise, recognizing much Native American conquest as war to produce empty space helps explain patterns of violence across the early modern period and beyond. Success put more distance between them and their enemy and expanded a fruitful hunting zone. There was no implied need for subjugation or population control. But it did require the enemy to move away. This meant that Native American warfare used violence to frighten – to create a sense of vulnerability. Their systems of warfare were not designed to allow for wholesale incorporation – individual adoptees yes, but they had no use for a generalized accession of territory with population, because they lacked the latent force potential to secure them. Thus the epigram at the opening of this chapter explaining Cherokee motives: they wanted revenge and to terrify their opponents. But when used against state-sponsored settlers, Native American styles of violence designed to frighten ran into an enemy that did not want to move. The demographic wave of European settlers quickly refilled whatever land had been temporarily emptied by Native American attacks, and Native Americans may have felt compelled to escalate the frightfulness of their attacks. Early attacks, like the Powhatans against the Jamestown colonists, or the Tuscaroras in North Carolina, or the Pequots in New England, have been interpreted as messaging attacks, not the onset of all-out territorial war. It was indeed real violence, but also symbolic and designed to strike fear. In this context they engaged in the posing of bodies, stuffing dirt or bread in the mouths of the dead and so on.43 It is not unreasonable to suggest that Indian violence escalated in the next generation’s warfare, having found that selective killing and pointed symbolism were not terrifying enough to push back white settlement.

European armies operating in North America were frustrated both by geographical obstacles to their usual logistical system and by the expectations of their opponents about what victory meant. As the English colonized North America they went through a series of reactions to the problems posed by its logistical environment, the nature of Indian resistance, and their own expectations of conquest. As we have seen, standard practice in state-on-state conquest often first attempted to impose a vassal or tributary status. It is easy enough to find such attempts in play in the early Virginia colony. The English literally labelled Powhatan a vassal of King James, complete with an intended submission ceremony, and they would attempt similar measures in many places around the continent. In some ways there was congruent conceptual ground here, since the Native Americans themselves had a somewhat parallel mechanism for tributary status.44 English expectations of tribute, however, were more expansive, hierarchical, and expected profit from the bulk delivery of goods, whereas Native American versions of tribute, with some exceptions, tended to focus on key status goods rather than bulk subsistence. The increasing English demands for com-plete submission on their terms led to violence, which gave rise to Native resistance – quickly labelled ‘rebellion’. Alternatively, in some English colonies the English waged or spurred campaigns of enslavement to procure labour, sometimes for local use, sometimes for profitable export. Those efforts generated traumatic effects around the south-east, finally spurring such a backlash from the Indian population that African slaves became preferred.45 Indian resistance, labelled rebellion, then suggested a shift to the more comprehensive alternative of displacement followed by settler provincialization.

Repeatedly, over the course of the next two hundred years (at least), the English and later the Americans would win a perceived victory over a group of Native Americans, often concluded by a treaty surrendering territory to white settlement, and then face the challenge of provincialization, which seemed to require the distribution of latent force across a very expansive territory. In Native North America, however, that norm quickly broke down. First, the density of the white population on the frontier did not provide sufficient organic logistical support to sustain a garrison from local resources (both in the sense of transport routes and population density producing subsistence surpluses). Worse, when Native Americans launched attacks in that environment many settlers fled, further reducing nearby logistical capacity.46 Frontier forts proved expensive and vulnerable over and over again (as they had done in sixteenth-century Ulster too).

The first attempted solution to this problem was to build the necessary infrastructure, as previous empires had done through frontier fortification and road systems. That too, in North America, proved expensive and vulnerable. In the words of a contemporary analyst:

Those who have only experienced the severities and dangers of a campaign in Europe, can scarcely form an idea of what is to be done and endured in an American war. To act in a country cultivated and inhabited, where roads are made, magazines are established and hospitals provided; where there are good towns to retreat to in case of misfortune; or, at the worst, a generous enemy to yield to … But in an American campaign every thing is terrible; the face of the country, the climate, the enemy. There is no refreshment for the healthy, nor relief for the sick. A vast unhospitable desart [sic], unsafe and treacherous, surrounds them, where victories are not decisive, but defeats are ruinous.47

Meanwhile and equally relevant, early seventeenth-century English hopes that con-quest would capture labour (in addition to land) also fell flat as Native Americans followed their own pattern of moving away in the face of defeat. We should see early Virginia reservations or New England Christian Indian ‘praying towns’ as exceptions to a more prevalent Indian pattern of vacating territory.

Lacking the preventative control of widely distributed garrisons, the British or American state then resorted to the punishment campaign designed to force a full population displacement. In one sense it was a resort to attempted tributary systems, in which campaigns were designed to terrorize populations into submitting. Fire and destruction were seen as necessary tools to impose the state’s will. Since campaign armies, in the absence of their normal logistical system depending on local food production, could only pass through the territory and could not occupy it, they resorted to destruction. This strategy represented an escalation of violence driven by incompatible structures of conquest. To be sure, the strategy was not unfamiliar or unknown to Europeans. States in medieval Europe, for example, usually lacked the capacity for full territorial conquest and resorted to devastation raids (chevauchée) instead.48

To use a different region as another example, Thomas Robert Bugeaud, fighting in Algeria in the 1840s, argued for a scorched earth policy of razzias, designed to destroy settlements, crops, and so on. He argued that the only thing of value there would be ‘the agricultural interest spread over the whole surface of the country’.49 In an essay on Algeria, written in 1841, the famous Alexis de Tocqueville, understating the worst implications of razzias, characterized them as ‘unfortunate necessities’.

If we do not burn harvests in Europe, it is because in general we wage war on governments and not on peoples … We shall never destroy Abd el-Kader’s power unless we make the position of the tribes who support him so intolerable that they abandon him. This is an obvious truth. We must conform to it or give up the game. For myself, I think that all means of desolating these tribes must be employed.50

In the long term, state control in these environments emerged through the importation of enough colonists to create the demographic infrastructure to sustain garrisons (and who themselves constituted a militia as a kind of latent force). Consider, for example, the changes wrought by settlement in Ohio. American military campaigns in Ohio in the 1780s and 1790s struggled or were outright destroyed. Anthony Wayne’s 1794 campaign finally resulted in battlefield victory, but the real change was demographic: in 1793 there were about 3,220 settlers in Ohio; this had increased to 5,000 by 1796, and by 1801 to 45,000.51 General Josiah Harmar, posted in eastern Ohio in 1785, set his lieutenant, Ebenezer Denny, to count the settlers moving on the river past the fort. Eventually there were enough settlers and Harmar moved his headquarters further downriver and built a new fort in present-day Cincinnati.52 Those settlers frequently ignored whatever fragile structures of law the state had created to regulate relations with the indigenous peoples and instigated violence to displace them yet further away.53 Native American displacement in such cases was normal to their form of warfare that sought to empty land, but from the state’s perspective it proved initially frustrating to hopes of control – although by the 1790s such displacement had become the primary goal of the new American state. A similar situation had plagued English colonists in Ireland, who were frustrated by the mobility of Irish labour, whose wealth was invested more in their cattle than their land. ‘Frustration’ in this case generated further violence. The mobility of the Irish became defined as part of their ‘savagery’, and it entered into the roll call of the rationalizations of violence. In the longer term it also led to the violence of deracination. The conqueror, relying on bureaucracy and often on missionary work to change the structures of sanctity, both backed by latent force, forcibly acculturated the conquered. The losers had to be made to fit the winners’ expectations of conquest, no matter how violent that process might be.

The early modern world played host to a wide variety of subsistence systems with different expectations of military victory; globalizing contact, trade, and conflict after 1500 put many of those societies into contact for the first time. The model outlined here allows us to go beyond the war rhetoric of the literate and discern how violence also sprang from fundamental structural differences. Material constraints affected practice, practice became norms, and violated norms then produced vio-lence qualitatively and even quantitatively unrelated to the nominal goals of the conflict. Over time, and sometimes very quickly, the playing out of such violence produced ideologically freighted words like ‘barbarian’, ‘savage’, and ultimately ‘colonist’. The rhetoric, the processes, the institutions, and above all the violence of acculturation arose not just from cultural demonization or prejudice, but from the underlying logistics of conquest and the resultant set of expectations about what one gained from victory.

Endnotes

- J. Buchan (ed.), Essays and Apothegms of Francis Lord Bacon (London, 1894), p. 219.

- S. Qian, Records of the Grand Historian: Qin Dynasty, trans. B. Watson (Hong Kong and New York, 1993), pp. 80–1.

- P. Kahn, The Secret History of the Mongols (Boston, MA, 1998), p. 65.

- G. Chicken, ‘Journal of the March of the Carolinians into the Cherokee Mountains, in the Yemassee Indian War, 1715–16’, Yearbook of the City of Charleston (1894), p. 342.

- The wide coverage of this chapter and the limitations of space preclude a full recitation of sources. All of the claims made in the chapter are part of a larger ongoing project, tentatively titled ‘The Pillars of Conquest: Consolidating Victory in the Preindustrial World’. Quite a number of people have been very helpful on this project and I am especially grateful to Erica Charters, Marie Houllemare, and Peter Wilson for including me. In addition, my thanks go to Timothy May, Liz Ellis, Stephen Morillo, Clifford Rogers, and Rhonda Lee.

- There are few works on this subject. Key entries include: M. Mann, The Sources of Social Power, Volume 1: A History of Power From the Beginning to AD 1760, new ed. (New York, 2012); N. Schadlow, War and the Art of Governance: Consolidating Combat Success into Political Victory (Washington, DC, 2017); P. M. R . Stirk, A History of Military Occupation From 1792 to 1914 (Edinburgh, 2016); D. Day, Conquest: How Societies Overwhelm Others (New York, 2008); J. Landers, The Field and the Forge: Population, Production and Power in the Pre-Industrial West (New York, 2003); C. J. Rogers, ‘Medieval Strategy and the Economics of Conquest’, Journal of Military History, 82:3 (2018).

- It is important to emphasize that even in wars arguably not caused by resource conflict, such as revenge raids, blood feuds, or wars for god or glory, the victor quickly moved to take advantage of newly available resources. This model addresses those processes, not war causation as such.

- Obviously there were other systems of subsistence, but these three can demonstrate the model.

- W. E. Lee, Barbarians and Brothers: Anglo-American Warfare, 1500–1865 (Oxford and New York, 2011).

- I derive this distinction from the work of H. Arendt. See her ‘On Violence’, in N. Scheper-Hughes and P. Bourgois (eds), Violence in War and Peace: An Anthology (Malden, MA, 2004).

- The most sophisticated treatment of this larger problem within states is Mann, Sources of Social Power. He identifies Economics, Ideology, Military, and Political as his primary categories. My analysis differs primarily by focusing in on how the ‘military’ piece is fundamentally dependent on logistics.

- Lee, Barbarians and Brothers, pp. 51–3; W. E. Lee, ‘Keeping the Irish Down and the Spanish Out: English Strategies of Submission in Ireland, 1594–1603’, in W. Murray and P. Mansoor (eds), Hybrid Warfare: Fighting Complex Opponents from the Ancient World to the Present (Cambridge, 2012), pp. 60–1.

- The conversion of ‘commanderies’ to ‘counties’ in ancient China represents a parallel case: M. Loewe and E. L. Shaughnessy, The Cambridge History of Ancient China: From the Origins of Civilization to 221 BC (Cambridge, 1999), pp. 613–16, 998.

- B.-O. Bold, Mongolian Nomadic Society: A Reconstruction of the ‘Medieval’ History of Mongolia (New York, 2001), p. 42.

- This characterization of Chinggis Khan’s rise and the various types of victory consolidation in Table 13.2 are based on a close reading of every incident of ‘victory’ in the so-called Secret History and accords with David Morgan’s general interpretation. Kahn, Secret History, pp. 48, 51–2, 58–9, 62, 65, 68; D. Morgan, The Mongols, 2nd ed. (Malden, MA, 2007), p. 34.

- The issue of ‘slavery’ among nomads is complex, but see T. D. Skrynnikova, ‘Relations of Domination and Submission: Political Practice in the Mongol Empire of Chinggis Khan’, in D. Sneath (ed.), Imperial Statecraft: Political Forms and Techniques of Governance in Inner Asia, Sixth–Twentieth Centuries (Cambridge, 2006), esp. p. 93.

- See D. Sneath, ‘Imperial Statecraft: Arts of Power on the Steppe’, in Imperial Statecraft, pp. 1–22; D. Sneath, The Headless State: Aristocratic Orders, Kinship Society, and Misrepresentations of Nomadic Inner Asia (New York, 2007). Sneath would prefer to discard ‘tribe’ and even ‘tribal confederation’ as descriptive terms, but we believe they retain value in this comparative context.

- The transition from traditional steppe methods of conquest to the use of local rulers or centrally imposed bureaucrats in the Mongol Empire was complex and varied by region and over time. For one survey, see T. May, The Mongol Conquests in World History (London, 2011).

- P. B. Golden, ‘War and Warfare in the Pre-Cinggisid Western Steppes of Eurasia’, in N. Di Cosmo (ed.), Warfare in Inner Asian History, 500–1800 (Leiden, 2002), p. 130.

- Both John of Plano Carpini and William of Rubruck (based on travels deep into the Mongol Empire) wrote that meat was reserved for the winter season; mare’s milk was the primary food during late spring, summer, and autumn. They also indicate that one sheep could feed multiple men; Rubruck even specified 100 men per sheep: C. Dawson (ed.), Mission to Asia (Toronto, 1980), pp. 17, 63, 97–8. It was probably more varied: hunting was a supplement especially in summer and autumn; fermented milk was still available in early winter. A calorie count confirms these contemporary observations. One mare can provide a 0.6 gallons/day at c.2,700 calories. One pound of mutton is c.1,340 calories and one sheep produces at least 120 half-pound servings. Adding the need for horses to carry burdens as well as produce milk, this results in the traditional warrior’s string of five horses and one sheep as providing 120 days of meat and 280 days of mare’s milk (the meat being shared). See note 21 for more citations.

- This is a summary of a complex issue; starting points for these calculations are: D. Sinor, ‘Horse and Pasture in Inner Asian History’, Oriens Extremus, 19:1–2 (1972), p. 182; H. J. Wiens, ‘Geographical Limitations to Food Production in the Mongolian Peoples Republic’, Annals of the American Geographers, 41:4 (1951); J. M. Smith Jr., ‘Hülegü Moves West: High Living and Heartbreak on the Road to Baghdad’, in L. Komaroff (ed.), Beyond the Legacy of Genghis Khan (Leiden, 2012); J. M. Smith Jr., ‘Ayn Jalut: Mamluk Success or Mongol Failure?’, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 44:2 (1984); D. Morgan, ‘The Mongol Armies in Persia’, Der Islam, 56:1 (1979); Z. Pinke et al., ‘Climate of Doubt: A Re-Evaluation of Büntgen and Di Cosmo’s Environmental Hypothesis for the Mongol Withdrawal from Hungary, 1242 CE’, Scientific Reports, 7:12695 (2017); U. Büntgen and N. Di Cosmo, ‘Climatic and Environmental Aspects of the Mongol Withdrawal from Hungary in 1242 CE’, Scientific Reports, 6 (2016); R . P. Lindner, ‘Nomadism, Horses and Huns’, Past & Present, 92 (1981). The approximation here is supported by a general estimate from Dr Jamsranjav Bayarsaikhan (National Museum of Mongolia) of typical nomadic family pasture requirements. I am grateful to Timothy May for many (and continuing) conversations on this issue.

- Morgan, Mongols, p. 57; Kahn, Secret History, pp. 148, 156; P. Ratchnevsky, Genghis Khan: His Life and Legacy (Oxford, 1991), pp. 104–5, 140–1; C. F. Sverdrup, The Mongol Conquests: The Military Operations of Genghis Khan and Sübe’etei (Solihull, 2017), pp. 98–9, 166–7; H. Franke and D. C. Twitchett (eds), The Cambridge History of China, vol. 6, Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368 (Cambridge, 1994), pp. 208–13.

- R . J. Chacon and R . G. Mendoza, The Ethics of Anthropology and Amerindian Research: Reporting on Environmental Degradation and Warfare (New York, 2012), Preface and Introduction.

- D. J. Silverman, Thundersticks: Firearms and the Violent Transformation of Native America (Cambridge, MA, 2016), p. 9.

- W. M. Denevan, ‘The Pristine Myth: The Landscape of the Americas in 1492’, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 82:3 (1992); W. Cronon, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists and the Ecology of New England (New York, 1983).

- For just one example, see P. A. W. Wallace, Indian Paths of Pennsylvania (Harrisburg, PA, 1965).

- I am preparing a separate article on the details of Native American campaign logistics in this period, tentatively titled ‘“The Indians are Hunting”: Native American Expeditionary Logistics and the Problem of Territorial Conquest’.

- There are many examples. Representative stories can be found in R . VanDerBeets (ed.), Held Captive by Indians: Selected Narratives, 1642–1836 (Knoxville, TN, 1994), pp. 12–13, 53–4, 136–7.

- Lee, Barbarians and Brothers, pp. 151–5.

- W. E. Lee, ‘Peace Chiefs and Blood Revenge: Patterns of Restraint in Native American Warfare in the Contact and Colonial Eras’, Journal of Military History, 71:3 (2007), p. 724.

- Ibid., pp. 713–14, 723.

- Modern estimates suggest that ‘on the average property, it will take around 25 acres of native woods or 5 acres of openings (re-growth) to support a single deer in good health’: https://www.northamericanwhitetail.com/2010/09/22/deermanagement_naw_aa902landscaping/ (accessed 10 Mar. 2020). In autumn 2003, Kentucky’s Owen County had the highest average deer population at 47/square mile (= 47/640 acres): https://www.kdfwr.state.ky.us/fall03mg1.asp. Unfortunately this source is no longer available online, but was also consulted by this researcher: https://www.maa.org/book/export/html/115877 (accessed 10 Mar. 2020), who reports the same numbers as I recorded at the time of writing.

- The data in Map 13.3 is derived from W. E. Lee, ‘Fortify, Fight, or Flee: Tuscarora and Cherokee Defensive Warfare and Military Culture Adaptation’, Journal of Military History, 68:3 (2004).

- D. La Vere, The Tuscarora War: Indians, Settlers and the Fight for the Carolina Colonies(Chapel Hill, NC, 2013), pp. 183, 196; A. Gallay, The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670–1717 (New Haven, CT, 2002), pp. 41, 55–6; B. G. Trigger, Natives and Newcomers: Canada’s ‘Heroic Age’ Reconsidered (Kingston and Montreal, 1985), pp. 263–73.

- T. E. Davidson, ‘Relations between the Powhatans and the Eastern Shore’, in H. C. Rountree (ed.), Powhatan Foreign Relations, 1500–1722 (Charlottesville, VA, 1993), pp. 146–7, 150; W. Strachey, The Historie of Travell into Virginia Britania (1612), ed. L. B. Wright and V. Freund (London, 1953), p. 87; R. D. Ruediger, ‘Tributary Subjects: Affective Colonialism, Power and the Process of Subjugation in Colonial Virginia, c.1600–c.1740’ (PhD Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2017), passim.

- F. Jennings, The Ambiguous Iroquois Empire (New York, 1984), pp. 154–5, 159–61. There are other examples of the absorption of people as a blend of tributary and adoption, includ-ing the hopes of the Narragansett allies of the English in 1637, who lamented the killing of so many Pequots at Mystic whom they had hoped to control after their defeat. Lee, Barbarians and Brothers, pp. 154–5.

- D. K. Richter, ‘War and Culture: The Iroquois Experience’, William and Mary Quarterly, 40:4 (1983).

- F. Speck, ‘The Delaware Indians as Women’, Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 70:4 (1946), pp. 384–5; J. Miller, The Delaware as Women: A Symbolic Solution’, American Ethnologist, 1:3 (2009). This issue is the subject of some debate, and even the Iroquois and the Delaware may have interpreted its meaning differently, much less our European witnesses.

- ‘A Map of Virginia’, in P. L. Barbour (ed.), The Complete Works of Captain John Smith (3 vols, Chapel Hill, NC, 1986), I, pp. 166–7.

- J. J. L. Gommans, ‘Warhorse and Post-Nomadic Empire in Asia, c.1000–1800’, Journal of Global History, 2:1 (2007), p. 14; Morgan, The Mongols, pp. 64–5.

- To be sure, when steppe nomads became conquerors they learned to demand sedentary troops from their victims, who often served as garrison forces in sedentary lands.

- Golden, ‘Pre-Cinggisid’, p. 155.

- Frederic Gleach called this an Algonquin ‘aesthetic’ of war. For examples of such symbolic violence messaging see: F. W. Gleach, Powhatan’s World and Colonial Virginia: A Conflict of Cultures (Lincoln, NE, 1997), pp. 157–69; T. C. Parramore, ‘The Tuscarora Ascendancy’, North Carolina Historical Review, 59:4 (1982); W. L. Saunders (ed.), The Colonial Records of North Carolina (10 vols, Raleigh, NC, 1886–90), I, p. 826.

- A key source on this congruence in tributary thinking is Ruediger, ‘Tributary Subjects’.

- Gallay, The Indian Slave Trade.

- See the contemporary judgement in The Journals of Major Robert Rogers & An Historical Account of the Expedition against the Ohio Indians in the year 1764, under the Command of Henry Bouquet, Esq. (Dublin: R . Acheson, 1769), facsimile reprint as Warfare on the Colonial American Frontier (Bargersville, IN, 1997), pp. viii–ix.

- Warfare on the Colonial Frontier, pp. xiv–xv.

- C. J. Rogers, War Cruel and Sharp: English Strategy Under Edward III, 1327–1360 (Woodbridge, 2000); Rogers, ‘Medieval Strategy’.

- Quoted in J. E. Sessions, ‘“Unfortunate Necessities”: Violence and Civilization in the Conquest of Algeria’, in P. M. E. Lorcin and D. Brewer (eds), France and its Spaces of War: Experience, Memory, Image (New York, 2009), p. 31.

- A. de Tocqueville, ‘Essay on Algeria (October 1841)’, in Writings on Empire and Slavery, ed. and trans. J. Pitts (Baltimore, 2001), pp. 70–1.

- C. G. Calloway, The Victory with No Name: The Native American Defeat of the First American Army (New York, 2015), p. 153.

- E. Denny, Military Journal of Major Ebenezer Denny: An Officer in the Revolutionary and Indian Wars (Philadelphia, 1859), p. 241.

- Parallel examples of those on the frontier provoking violence to enable conquest include Caesar in Gaul and the ‘New English’ in sixteenth-century Ireland.

Chapter 13 (236-260) from A Global History of Early Modern Violence, edited by Erica Charters, Marie Houllemare, and Peter H. Wilson (Manchester University Press, 09.01.2020), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.