Our understanding of horizontal learning within medieval communities largely depends upon semantics.

By Dr. Tjamke Snijders

Medieval Hisorian

Katholieke Universiteit Leuven

Abstract

This contribution sketches a conceptual history of the ideational component of community in the field of medieval studies. It shows that medieval scholars have usually proceeded from a ‘strong’ definition of communities, emphasized geographical boundaries, posited the importance of consensus, and focused on a common denominator that could be used to characterize the community. The traditional approach to community can be contrasted with the concept of a ‘Community of Practice’, which defines a community as a practice-based social group whose identity is based on shared performances of a repertoire that is in constant flux. An implementation of this approach can provide medievalists with the tools to re-interpret medieval communal identities as multiform and caught up in a continual process of renegotiation; and what this means for the way we conceptualize communal learning.

Introduction

Our understanding of horizontal learning within medieval communities largely depends upon the way we define our terms. First, we need to clarify what it meant to ‘learn horizontally’ within a medieval community, and this addresses this issue from a variety of approaches. Less obviously, but no less crucially, we also need to clarify what it meant to be part of a ‘community’ in which learning was taking place.

How we, as scholars, delineate ‘community’ directly influences how we understand communal learning. If we define a community as a close-knit social group that is bound to a specific place, we can readily imagine farm boys learning the skills of rural life from their peers. If, however, we define community as a pure construct, an imagined ‘us’ versus ‘them’ that could cut across boundaries as well as generations, horizontal learning might take a very different shape.

Unfortunately, it is far from easy to propose a suitable definition for the term community. Scholars have used this term ‘with an abandon reminiscent of poetic license’,1 which has turned it into something ‘as indefinable – as well as indispensable – as the term “culture”’.2 Medieval scholars first used the word community to describe small villages, such as Le Roy-Ladurie’s Montaillou. Not long after, the idea of ‘community’ started to broaden. It came to encompass much wider geographical areas; and also started to include social groups such as Christians, peasants, and women; and even covered such abstract notions as ‘textual communities’ and ‘imagined communities’.3 By 1955, 94 discrete definitions of ‘community’ had already been proposed.4

This study gives a selective – but, I hope, relevant – overview of the definitions of community that are germane to the perspective of medieval learning. The first section shows that the term community has traditionally been equated with a significant level of uniformity among the members of a social group, which engenders a conception of horizontal learning as a form of socialization.5 The second section discusses a conflict-based definition of community and considers horizontal learning as a tool for identity politics. The final section delves into the model of the ‘Community of Practice’ and proposes a role for horizontal learning that is central to the formation of the community itself.

Community Based on Uniformity

Strong Communities

In discussing the definition of medieval communities, it is important to distinguish between relational and ideational approaches to the subject.6Relationalists investigate the observable connections between members of a social group. A relationalist could, for example, investigate to what extent the medieval nobility can be understood as a delineable social group in a late medieval urban setting by studying its marriage networks.7 Such scholars often employ a prosopographical method to inquire into their subjects’ social backgrounds, economic status, political ideologies, and relationships.

Ideationalists, in contrast, study the tools that were crucial to form a collective identity: the objects, texts, speech acts, and practices that enabled a group of people to experience itself as one.8 This research perspective proceeds from the assumption that the experience of homogeneity is a sine qua non for any community. As John Dewey put it, ‘Men live in a community in virtue of the things they have in common’, adding that ‘communication is the way in which they come to possess things in common’.9

This idea of homogeneous communities implicitly leans on a robust intellectual tradition that can be traced at least as far back as Rousseau (1712-1778). He had considered differences in beliefs and values to be intolerable threats to group cohesion and, therefore, to nation-states. He famously argued that all persons in a society must give up their individual desires and aspirations as they, in a sense, sign the social contract: ‘Chacun de nous met en commun sa personne et toute sa puissance sous la suprême direction de la volonté générale; et nous recevons en corps chaque membre comme partie indivisible du tout’.10 Although Rousseau conceded that individual minds and desires would never cease to exist, he argued that they must be regulated in such a way that the wishes of the one do not hamper the wishes of the many. In order to do so, the community must be able to focus on one common symbol that can serve to unite it, such as the person of a ruler. For Rousseau, then, a community could only be formed through ‘consensual agreement, a monistic set of opinions and sentiments concerning the public good, coupled with the conviction that there is but one correct way of perceiving it and of pursuing it’.11 The assumption at the heart of this working definition is that social groups need a signif icant amount of internal consensus to achieve functional efficiency.12

Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803) partially endorsed Rousseau’s ideas. He agreed with the notion that a community must share an aspect of commonality, but he focused on the role of language. He argued that one’s maternal language determines the manner in which one thinks, as you can only think what you can express linguistically (Denkungsart): language determines thought. Herder maintained that the truths of one language community are not necessarily the same as those of communities that speak another language.13 Therefore, in his eyes, a common language together with established cultural traditions builds a ‘nation’ of people with a shared identity. The net result is a sense of ‘distinctive self ’ that is shared throughout the nation as ‘one national character’ or ‘a collective soul’.14

In contrast to Rousseau, Herder left room for dissent within this collective. He realized that even humans who share a language and a collective soul are still profoundly individual. Instead of emphasizing the necessity of consensus within a community, Herder underlined the idea of voluntary cooperation (Zusammenwirken) as the basis for citizenship for the members of an essentially pluralist Volk.15

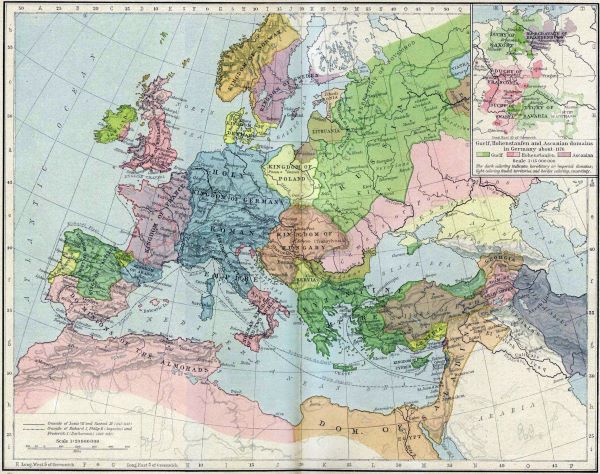

Continental nineteenth- and early twentieth-century medievalists took up these thoughts and viewed them primarily through the lens of their own nation-states. The German Leopold von Ranke (1845-1847) argued for the existence of a medieval German nation in his Deutsche Geschichte im Zeitalter der Reformation. The Belgian Henri Pirenne (1899-1932) studied the history of the civilisation belge from the Roman era until the start of World War I, even though the Belgian state had only been founded in 1830.16

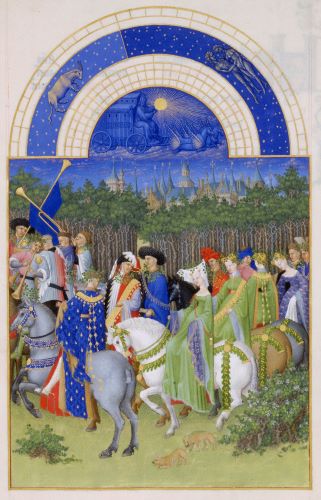

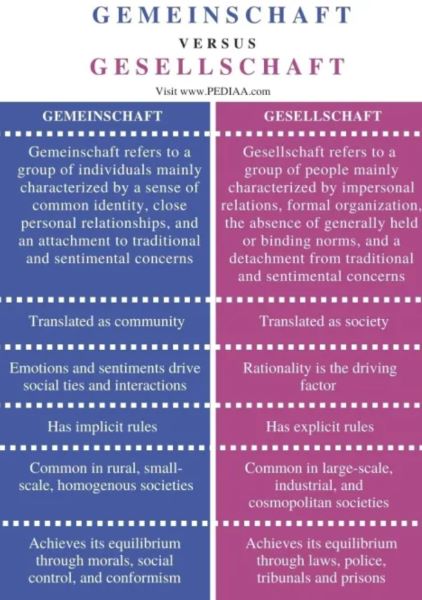

In the United Kingdom, where the need to legitimize the borders of the modern state was not felt as acutely, historians set out in search for communities of much smaller scale. They were looking for shared characteristics that could have determined the identity of a social group, focusing primarily on peasants’ relationships towards the common land.17 In 1887, the sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies argued that the place-bound character of life in rural villages created feelings of togetherness and mutual bonds between its members (the Gemeinschaft).18 Similarly, Paul Vinogradoff maintained in 1892 that medieval English villages were primitive communities, where monolithic masses of peasants lived in a harmonious world of collective solidarity and were primarily concerned with subsistence.19 These rural utopias were frequently contrasted with the individualism of modern society, the Gesellschaft, which is transregional, much more abstract, and much more selfish. According to Tönnies, one stays a member of a Gesellschaft not out of instinctive solidarity but because it can further one’s personal aims.20

Emile Durkheim (1893) embraced this instrumentalist notion of modern society. He argued that while members of primitive communities shared beliefs, representations, ideals, and feelings because they were all very much alike, the members of more complex societies that practice the division of labour do not stick together because they are inherently similar; they do so because they depend upon each other for survival, like different organs in one body. For Durkheim, their shared consensus is a necessary precondition to creating the social cohesion and solidarity that is required for seamless cooperation. Even though the members of a social group are inherently diverse, it is understood that this diversity is an obstacle that needs to be overcome by the group if it is to be successful.21

To what extent were medieval communities truly ‘primitive’, homogeneous, and very different from the more complex societies of modern times? In 1897, Maitland proposed that while English villages were indeed primitive at the outset, outside pressure quickly turned them into complex groups of individuals.22 More recently, scholars have argued that the primitive community never existed, even on the windy hills of the English countryside. Medieval societies ‘appear much more like the sixteenth century, where people and money flowed through the countryside, and where the individual was not born, married or buried amongst his kin’.23 As a result, the romantic notion of a primitive village community has been largely replaced by the idea of a village that was complex and characterized by heterogeneity as well as by social and geographical mobility.

Even though scholars have abandoned the idea that medieval communities were uniform and altruistic, the underlying notion that space was central to a community’s identity has remained current. Yet, whereas Tönnies essentially understood ‘space’ as ‘place’, Lefebvre famously argued that space is not a static geographical entity but is produced by people. Space is shaped by peoples’ daily activities, by the way space is represented on maps and in laws, and by peoples’ experiences of specific spaces.24 This definition has been utilized in many studies of the development of Western European identities, usually from the point of view of the interrelatedness between sacrality and city in the High Middle Ages, or through the lens of urban capitalism in later centuries.25 These studies all share the belief that the common identity of a specific social group is tightly entangled with its relationship to one particular space.

Ideationalists thus understand communities as systems of social conventions based on shared symbols (such as a ruler or a flag), a common language, or a specific space. These systems are ‘strong’ in the sense that scholars can conceivably isolate and codify them.26

The Language Perspective

While the debates over place and space as constitutive factors of communal identity continued, other scholars started to reconsider the importance of language. Rousseau’s idea that communities needed a significant amount of internal consensus now were combined with Herder’s argument that language is the most important communal element in any group.27

Leonard Bloomfield was the first to define a community explicitly through acts of speaking. He noted that ‘an act of speech is an utterance’ and that ‘within certain communities successive utterances are alike or partly alike’. He understood these likenesses in a purely vocal sense. For him, the phrases ‘the book is interesting’ and ‘put the book away’ are partly alike because they share the words ‘the book’; and the phrase ‘I’m hungry’ as spoken by a needy stranger is the same as the ‘I’m hungry’ that is uttered by a well-fed child who wants to delay bedtime. Bloomfield called any community that shares a repertoire of similar utterances a speech community.28

Seven years later, Otto Brinkmann passed from utterances to narratives and showed how communities can be shaped through passing on relevant stories. In Das Erzählen in einer Dorfgemeinschaft (1933), Brinkmann investigated the tales that were traditionally told in his native village of Obernbeck (Westphalia) when the villagers assembled in a mood of sociability (zwangloser Geselligkeit). He attempted to capture the form of these tales by hiding a stenographer in a side room, who was told to make phonetic notes of everything that was said. Brinkmann characterized Obernbeck as an Erzählgemeinschaft, or narrative community, because the entire village was actively involved in the storytelling.29

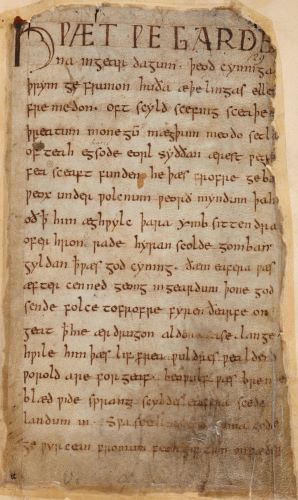

The idea of language-based communities has remained prominent in the work of linguistic anthropologists, who concentrate on the social interaction between same-language speakers and the results of linguistic diversity within such communities. Medievalists have never really embraced this particular approach to community formation, presumably because of the difficulty of studying oral interactions from written, pictorial, and material sources. If medievalists use the concepts of speech communities or narrative communities at all, it is usually in a study of the interrelationships between texts and oral interactions. Andrew Butcher, for instance, reframed the speech community as a ‘speech/text community’, a characterization that ‘represent[s] the discursive interaction of speech and text within a single cultural entity’.30

The 1960s were a watershed period in the study of community. In 1959, Erik Erikson kick-started debates about the nature of personal identity by defining it as self-sameness over time.31 This definition has remained at the basis of most theories of identity formation, although modern scholars generally see identities as less stable, not as a ‘property’ but as a collection of ‘projects and practices’.32

Then, in 1962, Thomas Kuhn fundamentally changed the study of group identities with The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.33 Somewhat similar to Herder, Kuhn argued that members of a community necessarily share a basic consensus about some of the essential elements of their existence (Kuhn famously called this basic consensus a ‘paradigm’). For Kuhn, members of two different communities are virtually unable to communicate fruitfully with one another, because there is no meta-language that one could use to translate statements from one paradigm to another.34

Kuhn’s influential thesis led scholars in the humanities to explore the possibilities (and epistemological pitfalls) of analyzing a community’s paradigm. Most scholars attempted to examine each community’s distinct matrix of theories of knowledge and religious convictions ‘from within’, without trying to fit their object of study into an evolutionary framework of ‘primitive’ and more ‘developed’ communities. One of the most influential scholars in this respect was Clifford Geertz, who introduced the concept of thick description in The Interpretation of Cultures (1973). It involves the collection of rich and detailed examples of the meaning systems within a community, which allows the socially constructed layers of meaning to be disentangled. The scholar can then read and interpret the community’s cultural practices as if they were a (complex) text.35

Literary scholars objected to the implication that it is ever easy to read and interpret a text. Interpreting a text is difficult because the meaning of a text is not objectively present in the text itself but is created by a community. ‘It is because words are heard as already embedded in a context that they have a meaning’, as Stanley Fish put it: the reader or readers who interacted with a text and with each other were thereby providing the text with meaning.36

A student of mine recently demonstrated this knowledge when, with an air of giving away a trade secret, she confided that she could go into any classroom, no matter what the subject of the course, and win approval for running one of a number of well-defined interpretive routines: she could view the assigned text as an instance of the tension between nature and culture; she could look in the text for evidence of large mythological oppositions; she could argue that the true subject of the text was its own composition, or that in the guise of fashioning a narrative the speaker was fragmenting and displacing his own anxieties and fears. She could not, however, […] argue that the text was a prophetic message inspired by the ghost of her Aunt Tilly.37

In short, some interpretations were supported by this student’s academic community, whereas others were (at least for the moment) rejected. In time, the scholarly consensus over the meaning of a text might shift. This observation led Fish to the idea of an interpretive community (1976): a present-day, academic community that occupies itself with the interpretation of a particular text, such as Hamlet or the Canterbury Tales, and shares a basic consensus about the possible meanings of that text.

One of the most exciting consequences of the work by Kuhn, Geertz, and Fish is that it undermined the old belief that communities must have clear geographical boundaries or share an organizational principle. Historians had become used to studying the characteristics of urban communities, village communities, monastic communities, county communities, agricultural communities, or Jewish communities in clearly defined geographical areas.38 Yet Kuhn, Geertz, and Fish all envisaged communities as groups of people with frequent social interactions who share a matrix of social conventions and worldviews that can be isolated, studied, and possibly even compared to other communities’ conventions and worldviews. Their work prompted historians to define a community in terms of texts and ideologies instead of geographical boundaries.

Outside the field of medieval history, historians applied the idea that communities did not need geographical boundaries to the question of nationalism. Benedict Anderson coined the concept of an imagined community (1983) that is not based on everyda`y, face-to-face interaction between its members but on an individual’s perception that he or she is part of the community.39

Among medievalists, narrative texts were considered the most promising inroad to study communities that were defined by texts and ideologies. Chronicles in particular combined information about communal bonds, social relationships, and ideological convictions. As religious authors produced so many chronicles, medievalists started to focus on religious communities. Caroline Walker Bynum compared twelfth-century Cistercian ideas about friendship and community to the ideas of Benedictine monks; other scholars scrutinized how Aelred of Rievaulx, Augustine, Anselm, and other authorities envisioned their respective communities; and various related lines of enquiry were opened up.40

In 1983, in his much-cited book The Implications of Literacy, Brian Stock discussed the idea that texts and community are closely interrelated. This book presented the concept of a textual community, which essentially trans-planted Fish’s interpretive community to the Middle Ages. Stock defined the textual community as a group of people whose social activities are centred on a text. He did not clearly define what exactly he meant by ‘text’ – a ‘deliberate opaqueness’ that may well have been a primary reason why the notion of textual community found great success among historians.41 According to Stock, a community could be gathered around ‘a text’ as well as ‘texts’, and these texts did not need to have written form. Basically, a text could be anything, ‘for, like meaning in language, the element a society f ixes upon is a conventional arrangement among the members’.42 The text could be a story, a physical manuscript, a ritual, or something else entirely. This broad definition of ‘text’ implies that all physical or mental objects could form the core of a textual community, as long as the community members shared a certain interpretation as to the meaning of this ‘text’.43

Stock underlined that it was not self-evident that a community came to share an interpretation of a ‘text’. Especially when the ‘text’ was a collection of written words, most members could not have read and discussed their text like the students in an interpretive community, because the community’s members were often semi-literate. Stock, therefore, proposed that the meaning of a medieval ‘text’ was enunciated by a literate interpreter, whose teachings were accepted by the community members and led to shared goals.44 This definition of textual communities quickly became a central concept to historians.45 Because of his emphasis on communality, Stock is not usually interpreted as leaving much room for dissent among community members. As Leidulf Melve put it, ‘The characteristic trait of [the textual community] is the extent to which the interpretation of a text provides for the social identity and cohesion of the entire community’ [my italics].46

Meanwhile, Fish’s idea of an interpretative community was pushed in another direction by researchers in composition studies, who occupy themselves with the question of how children and students learn to write. Their learning practices obviously happen in communities that resemble interpretative communities, and composition scholars wondered where they could situate the social boundaries between various groups of students and their idiosyncratic writing practices. Martin Nystrand answered this question by introducing the concept of discourse community (1982). As originally used, the discourse community was defined as a set of collective norms that influences writing practices.47 The definition was soon extended to include language because groups of people tend to share a specif ic discourse as well as a worldview. Patricia Bizzell tentatively def ined a discourse community as

a group of people who share certain language-using practices. These practices can be seen as conventionalized in two ways. Stylistic conventions regulate social interactions both within the group and in its dealings with outsiders; to this extent ‘discourse community’ borrows from the sociolinguistic concept of ‘speech community’. Also, canonical knowledge regulates the world views of group members, how they interpret experience; to this extent ‘discourse community’ borrows from the literary-critical concept of ‘interpretative community’.48

The discourse community is close to Stock’s textual community in that it centres on a collection of texts and text-related subjects. Community members read and discuss that collection, but also produce new texts. To write a new text, a community member must first determine the text’s position within the group’s interpretative conventions. In other words, a writer can only produce texts that fit the customs of the community in which the writer is functioning.

Membership in a discourse community is taught, just like the membership of an interpretative community and – presumably – that of a textual community. It requires knowledge of the register, concepts, and expectations of a group – knowledge that can be acquired through training. Lack of training, or disagreement with the discourse that centres on the community’s texts, essentially excludes the individual from the discourse community.

The idea of the discourse community proved popular and was developed further in many publications, but medievalists only hesitatingly adopted the concept. Robert N. Swanson hypothesized in 1995 that Christendom might be portrayed as a series of discourse communities, ‘sharing perceptions, aspirations, and vocabulary, and operating independently at a variety of levels; but all cohering in the umbrella discourse community of “orthodoxy”’,49 and Peter Meredith echoed this definition as he argued that a discourse community might have existed in fifteenth-century Norfolk.50 However, possibly because this adaptation of the discourse community is hard to distinguish from Stock’s better-known textual community, it never gained much popularity among medievalists.

The Community Explosion

As the twentieth century came to an end, the maturing theories on the nature of communities stirred the enthusiasm of scholars in widely divergent domains. While early modernists reflected on the social constitution of communities in general, medievalists continued the search for relatively small-scale communities that exemplified a particular form of knowledge or identity.51

One of the most influential new approaches was the concept of a political community. A number of dissertations from the early 1980s used the concept, and Susan Reynolds used it to study medieval social groups in their relationship to law and politics.52 She was not primarily interested in geographically delimited communities, or even in cultural or ideational communities; she believed that the key to medieval communities could be found in their associations. She focused on social groups that performed certain collective activities that were determined and controlled by shared values and norms, while the relationships between community members were ‘characteristically reciprocal, many-sided, and direct’.53 Unsurprisingly, the idea of political communities quickly became linked to the formation of theories about the growth of the early modern state.54

A second new approach to medieval communities started with Barbara Rosenwein’s worries about medieval emotions and the subsequent publication of her book on emotional communities in the Early Middle Ages (2006).55 An emotional community, according to Rosenwein, ‘is a group in which people have a common stake, interest, values, and goals’.56 As a result, they

are largely the same as social communities – families, neighbourhoods, syndicates, academic institutions, monasteries, factories, platoons, princely courts. But the researcher looking at them seeks above all to uncover systems of feeling, to establish what these communities (and the individuals within them) define and assess as valuable or harmful to them (for it is about such things that people express emotions); the emotions that they value, devalue, or ignore; and the modes of emotional expression that they expect, encourage, tolerate, and deplore.57

An interesting aspect of the emotional community is that the element that brings the community together is not identical to the emotions that are being studied. The emotional community may have come together for various reasons – because its members were born into it, could afford a house there, practised a specific profession, were interested in particular texts, and so on. Yet the historian does not focus on that communal element but instead studies the emotional practices that presumably developed together with the community. In essence, Rosenwein’s emotional community is a more or less random social group that developed communal emotions.

A third approach focuses on forms of knowledge and practices of learning within social groups. Melve discussed intellectual communities (2007) a s social groups that consist of members with similar backgrounds that share some form of knowledge.58 Constant Mews and John Crossley took a leaf out of Rosenwein’s book by defining communities of learning (2011) as social groups in which people share a common interest (such as religious or political convictions, education, or the importance that they attached to ‘some discipline and to some set of texts’), but that they study to uncover systems of learning.59 Emily Thornbury studies the poetic community (2014) as a social group of ‘discerning readers and critics’ with a shared aesthetic, whose members judge the poems they read and thereby influence its authors.60

Summary

This dizzying list of communities – which, of course, is far from exhaustive – highlights three features that scholars keep coming back to. First of all, they give great importance to geographical boundaries and space, either because the community’s character is directly determined by the space it inhabits (e.g., the boundaries of the primitive village determine the boundaries of its Gemeinschaft) or, conversely, because the community is explicitly defined through its ‘transspatial’ character (e.g., a community that is defined as a shared interpretation or attitude). Work on this subject has evolved, as most nineteenth- and early twentieth-century historians focused on the presumed opposition between ‘primitive’ communities and the ‘placeless’ societies of modern times; whereas more recent work thematizes the complex relationships between identity and space.

Second, all definitions of community posit the importance of consensus between its members.61 The most striking example is probably Stock’s textual community, whose members share one single interpretation of a ‘text’ that was prescribed to them by a literate interpreter. Similarly, a discourse community revolves around a set of collective norms that its members share,62 the knowledge community shares a paradigm, an emotional community shares ‘a common stake, interest, values, and goals’, and so on. Some researchers explicitly state that dissent within a social group is a problem that should be overcome in order to construct and maintain a sense of community; many others simply ignore the question of dissent within the community.

Last but not least, there is always one common denominator that can be used to characterize the community. There is either a fundamental agreement about the basic working of society (Rousseau, Kuhn, Geertz, the political community); a shared language or linguistic environment (Herder, the speech community, the narrative community, the interpretative community, the textual community, the discourse community); shared emotional reactions to life’s challenges (the emotional community); or the shared self-perception of being a community member (imagined community). All these perspectives proceed from a strong definition of ‘community’ as a consensual and stable phenomenon with characteristics that are so crisp and clear that they can be highlighted and described as the community’s essence.

As a background for research into horizontal learning, this strong definition of community implies a relatively stable social group with few internal conflicts over issues that are truly important to the group as a whole. Horizontal learning in this kind of community would essentially come down to the process of socializing newcomers into a settled social group. This process would vary little from year to year, or from decade to decade, because the social group itself never changed much, and its norms and values endured. As a result, the learning content in these groups would be surprisingly stable.

A Multiplicity of Communities: A Challenge to Homogeneity

The strong definition of community has been the focus of much criticism. First of all, it has frequently been remarked that it would be a gross simplification to characterize any individual as part of one community only. All medieval men and women belonged to complex networks of multiple communities that overlapped, cooperated, and competed with one another. Barbara Rosenwein, for example, envisions medieval society as consisting of ‘a large circle within which are smaller circles, none entirely concentric but rather distributed unevenly within the given space’, in which the large circle represents an overarching community, whereas the smaller circles represent subordinate communities.63 She hypothesizes that medieval society consisted of multiple large circles that intersect with one another. Susan Reynolds reached a similar conclusion and noted that

One of the most striking characteristics of the collective activities which I discuss, moreover, seems to me to be that they seldom took place within the small, stable, all-embracing, and mutually exclusive groups which appear to form the ideal type of community. People seem to have been capable of acting collectively in all sorts of different and overlapping groups at once, largely relying in all of them on affective, voluntary cooperation.64

Medievalists have therefore started to reconsider the question of multiplicity in relation to community formation. To what extent were communities ‘nested’ (which is to say that they contained one another or overlapped), and how did this influence medieval identity formation? To what extent did communities influence one another? What happened to communal identities when the paradigms of various communities contradicted one another?

Furthermore, the idea that a community must be consensual and relatively homogeneous has been questioned. The consensual model threatens, on the one hand, to reduce the individual to ‘a sort of automaton, passively obeying the interiorized collective will’, and on the other to reify a community’s social conventions.65 Can a social group only be called a ‘community’ when its social conventions, emotions, organizational modes, and beliefs were so strong and coherent that they can be isolated and codified? Were medieval communities not inherently pluralist, and very conscious of differences in age, status, social capital, and wealth?

The answer, according to Peter Burke, is clear. The community ‘has to be freed from the intellectual package in which it forms part of the consensual, Durkheimian model of society’ because we cannot be assume that communities were homogeneous.66 Walter Pohl has added his voice to Burke’s by noting that communities exist not because they manage to overcome dissent, as Durkheim suggested, but because they channel conflict and privilege some types of conflict over others.67 Pohl noted that medievalists set too much store by sources that construct the image of a homogeneous community, and they have long treated the resulting image as if it were a pseudo-subject of history that has agency of its own: ‘the Franci waged war, and the ecclesia acted on earth in the name of God. It is not clear to everyone that these are abstractions’.68

Many medievalists who turned away from the ‘consensual model of society’ have started to look at its opposite, the ‘conflictual model of society’, which is historically associated with Thomas Hobbes, Max Weber, and Karl Marx.69 This model sees society as fragmented into groups and individuals who compete strategically and purposefully for social and economic resources.70

One of the most notable adherents of this model is Thomas Bisson. He has studied the opposition between ‘public’ and ‘private’ power within the framework of the old debate over the transformation of ‘feudal’ society around the year 1000. Bisson shows that the power that was held by a king or a count – ‘public’ power that could express itself in norms and laws – was essentially a form of consensus and homogeneity in medieval society. However, Bisson argues that this homogenizing power crumbled around the year 1000 so that people were henceforth compelled to fend for themselves, which led to ubiquitous conflicts between individuals and small social groups.71 Somewhat similar to the nineteenth-century historians who contrasted the consensual ‘primitive’ communities to its modern individualist counterparts, Bisson studied how and when the essentially consensual community of the Carolingians was replaced by its conflictual opposite.

Frederic Cheyette, Stephen White, and Patrick Geary spearheaded an alternative approach to conflict studies by investigating practices of disputing. They saw conflict not as the result of absent public authority but as a tool to construct and manipulate social order.72 These scholars argued that conflicts between people naturally engendered antagonism between individuals and groups, but that conflicts could also be a source of cohesion because they demarcated the boundaries between social groups: ‘individuals and groups, for whom neutrality was impossible, related to each other as amici – that is, those who are bound by a paxor friendship – or else as inimici – that is, those who face each other in a potential or actual state of war’.73 Even more important, new social groups were born when individuals or parties started a search for new alliances.74

In this view, conflicts did not detract from public authority. The laws and norms of counts and kings were latently present throughout the Middle Ages but were only important when people actually invoked them in the course of their disputes.75 As Warren Brown and Piotr Górecki argue, people used overarching concepts of ‘public’ authority when the situation was such that these concepts could be of advantage to them in their negotiations. For example, Charlemagne found that it was in his interest ‘to project an image of power based on the norms and ideology of public authority’. His subjects would sometimes come into conflict with people who based their image of power on different norms, and they would try to resolve the conflict by adopting Charlemagne’s norms.76

In essence, it is fair to say that conflict studies have reacted to the consensual model of society not by studying conflict in the heart of a community or by questioning the community’s fundamental homogeneity but by abandoning the community as the basis of analysis and replacing it by disputes at the level of individuals and small subgroups within the community. When conflict historians do study communities, they usually present the community as internally consensual – either because its members shared an instrumental focus on a common interest (such as the opposition to inimici) or because powerful groups were able to impose their discourse on subordinate groups and thereby achieve ‘consensus’.77

A different way of questioning the homogeneity of a social group is to study its memories. Medievalists have asked whether communities necessarily possessed ‘collective’ memories, in which there is no place for dissent. The founding father of these ‘memory studies’, Maurice Halbwachs, indeed described the shared memory of a group of people in 1925 and 1950 as its collective memory. As a student of Durkheim, Halbwachs emphasized the shared aspects of collective memory formation, arguing that individuals can only remember coherently and persistently within the context of a community.78 Rephrased in Kuhnian terms: an individual’s memories are irrevocably determined by the paradigm within which the memories are formed and recalled, as the memories are formed by the community’s language and its social standards of plausibility.79 This notion became so popular that ‘whether associated with Halbwachs or not, the assumption that social groupings of all types formed their identities around a shared interpretation of their common history figures among the core assumptions of current scholarly practice and of medieval scholarship, in particular’.80

Nevertheless, scholars started to challenge this notion of fundamental collectivity from the 1970s onwards. Jan Assmann proposed to subdivide Halbwachs’s collective memory into two subspecies. On the one hand was a traditional, long-lasting kulturelle Gedächtnis consisting of historical narratives and ancient cultural traditions that are often repeated and can sometimes have normative purposes. On the other hand, Assmann distinguished the relatively chaotic kommunikative Gedächtnis consisting of the memories of day-to-day events within a specific community. These memories either die together with the person who remembers them or may be passed on to next generations for a maximum of about 80 to 100 years.81

Michel Foucault took a somewhat different approach. Instead of subdividing Halbwachs’s collective memory into long-term and short-term memories, he suggested that we should oppose collective memory to the counter-memories within the same social group: the memories that are battling for dominance with the collective memory or are being repressed by it.82 His cautious suggestion was taken up by researchers of popular memory, who have adopted Foucault’s counter-memories to discuss the existence of various conflicting memories that strive for supremacy within subgroups of a single community.83 Popular memory in particular came to be understood as a continuous process of contestation and resistance.84

Peter Burke (1989) added a layer of complexity when he pointed out that many divergent memories and interpretations could exist within a community, making it useful to analyze the different memory communities within society.85 Burke’s idea led James Fentress and Chris Wickham in 1992 to coin the concept of social memory.86 Their basic argument was that particular social groups communicated about their individual memories and thereby negotiated a shared social memory that has particular importance for the constitution of that social group. Fentress and Wickham studied the social memories of ‘national groups’, ‘women’, ‘peasants’, and ‘the working class’.87 Piotr Górecki showed that it was equally valid from a methodological point of view to work the other way around: he started with a specific kind of memory (the memories of legal transactions) that was shared by people who thereby came to constitute a community of legal memory.88

The last important intervention in the memory debate was Wulf Kansteiner’s conceptualization of collective memories as fundamentally distinct from individual memories.89 He noted that collective memory tends to be treated as if it was an individual (‘autobiographic’) memory on a larger scale – which can be conveniently remembered, altered, or forgotten – instead of ‘shared communications about the meaning of the past that are anchored in the life-worlds of individuals who partake in the communal life of the respective collective’. Collective memories, according to Kansteiner, ‘are based in a society and its inventory of signs and symbols’ such as manuscripts, images, and scenes, fragments of literary works, jokes, buildings, and discourse. To study how these things formed collective memories, one must not only investigate the things themselves but their reception as well – a call that has been well heeded by anthropologists and historians but not particularly so by medievalists.90

These more complex views of how medieval communities functioned change how horizontal learning might have worked. Most importantly, it situates learning within a social environment that was inherently unstable. If communities can overlap, be nested, contain subgroups that cherish countermemories, and be generally prone to internal conflicts, it is likely that the membership of each community was in constant f lux. Opposing social groups held contradictory opinions and memories: court versus rebels, Catholic versus heretic, one city versus another, men versus women, adults versus children …91 Every individual shaped his or her mix of communal identities. A young Catholic woman could keep identifying as catholic and as a woman for life, but at the same time grow older (moving from the ‘child’ community into that of adults), get married and have kids (and join the community of married mothers), move from one town to another and become part of a new local community, and so on.

Communities of Practice

New Agendas

Even though conflict studies and memory studies reacted against the old notion of homogeneous societies, in practice they kept emphasizing the consensual aspects of the (smaller) social groups they study. Largely missing from the discussion is a weaker concept of community, which interprets communal identity as multiform and does not posit a necessary causal relationship between community formation and ideological consensus. The study of medieval communities needs to let go of the idea that ideational communities are necessarily built around a common interest or ideology that unites its members, and they must consider the possibility of a community that is based on practices.

In a way, practices have long been present in the study of communal identities. When Brinkmann hid a stenographer in a side room so that he could record the exact way in which his fellow-villagers told stories, he was recording practices. When Reynolds defined a community as ‘a social group that performed a specified range of collective activities, which in turn endowed the participants with routine roles, and perhaps with a sense of group identity’, she was defining a community in terms of its practices.93 These definitions see a community’s practices as an identifiable repertoire of shared actions, which increased the homogeneity of the community members who participated in them.

What makes practices an interesting inroad into the study of medieval communities, however, is the possibility that different community members could share practices without sharing a consensus. Even if they did not agree on a particular ideology or discourse, their individual goals may have aligned for a certain time in which they would work, speak, or play together. From such a point of view, a community is defined not as a stable system of social conventions that can be easily codified but as a process of constant renegotiation and change.

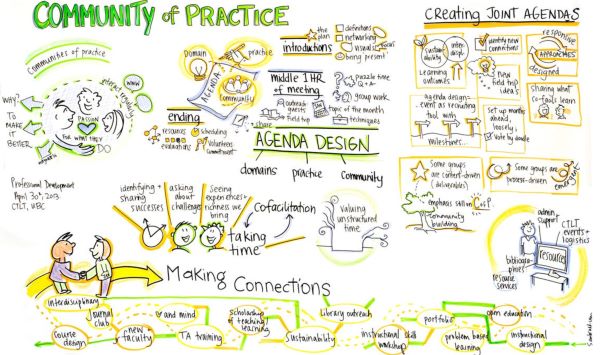

An interesting concept in this respect was introduced in 1991 by the social anthropologist Jean Lave and the Artificial Intelligence specialist Étienne Wenger. They studied how present-day corporations and Internet communities function and they concluded that they could be seen as communities of practice (CoP). Lave and Wenger defined this as a group of people who converge around an interest, a series of problems, or a specific subject – ‘things that matter to people’.94 Such a core interest can be the need to procure a basic necessity of life such as food or shelter, but it can also centre on an interest in a particular cultural phenomenon, religion, or text or even can be the need to perpetuate the existence of the community.95 The people who share this interest usually meet face to face to discuss it, but they do not have to be co-located.96 They can form ‘virtual communities of practice’ when they communicate online – or, from a medieval perspective, when they exchange books and written texts on the subject of their shared interest.

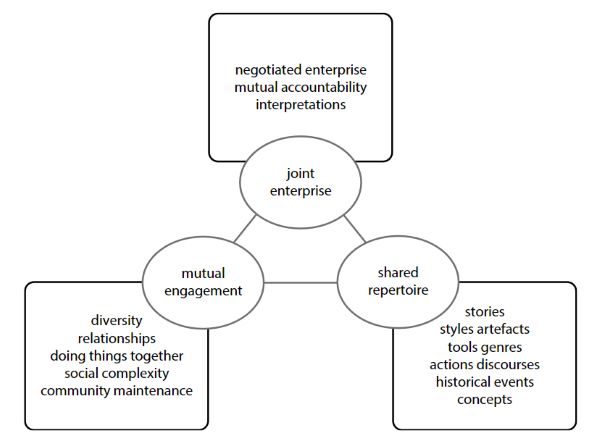

The members of a CoP learn from one another through a process of sharing information and experiences with the group. In so doing, they establish norms and build collaborative relationships (mutual engagement). This mutual engagement makes sure that the community members meet on regular occasions, discuss options, exchange information and opinions, work together, and influence each other’s thinking. These exchanges create a shared understanding of what binds the group members together (joint enterprise), though this understanding is never stable: the community members continually renegotiate it. In other words, the enterprise is not joint because everyone agrees with one another but because everyone is continually involved in the process of negotiating the question of what makes their community successful and liveable at any given moment.97 As the members of a community negotiate and pursue an enterprise, they create resources to negotiate meaning. These resources are their repertoire, which is defined as ‘the practices, words, tools, ways of doing things, stories, gestures, symbols, genres, actions and concepts that the community has created or appropriated in the course of its existence, and which have become part of its practice’.98

Lave and Wenger emphasized that these shared practices do not necessarily imply homogeneity, consensus, and coherence. On the contrary, the members of a CoP usually have many differences concerning age, gender, education, and specific interests, and create further variations in the process of working together. ‘They specialize, gain a reputation, make trouble, and distinguish themselves, as much as they develop shared ways of doing things’.99 Each member thus gains a unique identity within the community that is in dialogue with other members’ identities – but does not fuse with it. ‘Crucially, therefore, homogeneity is neither a requirement for, nor the result of, the development of a community of practice’, concludes Wenger.100

Nevertheless, the community must know a minimum level of coherence in order to function. This coherence requires work. The practice of any community, therefore, includes the work of community maintenance, which is the conscious effort to increase the community members’ sense of belonging to the community. Community maintenance can take many forms, such as circulating stories about the community’s worth and legitimacy.101

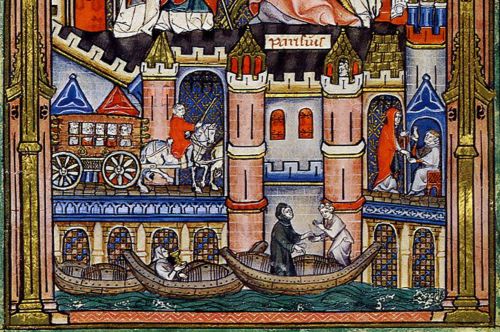

From the point of view of a medievalist, a high medieval monastery is the perfect embodiment of a community of practice. Monasteries could house dozens of monks, conversi, novices, and women. Though they often had diverse backgrounds, educational levels, ages, and riches, they shared their fundamental Christianity and their wish or need to live out their days within the compound of a monastery.102 To achieve that, they needed to safeguard the existence of their monastery. This required legitimacy: sufficient public standing to attract the novices, donations, and patrons that would keep the monastery running. There was no one clear way to achieve this. Some communities reformed and emphasized their newfound austerity; others chose to cling to old customs; yet others joined the order of Cluny, propagated the might of their patron saint, or focused on the economic exploitation of their possessions. Lave and Wenger would call the monks’ shared (though never stable) understanding of the best way to maintain their monastery’s legitimacy their joint enterprise.

In this sense, the ongoing discussion over the question of what makes a monastery legitimate def ined the monastic community. Meanwhile, the monks formed relationships and rules as they worked together to ensure the proper execution of the liturgy as well as the optimal economic, religious, and political management of the institution (their mutual engagement). While they were managing their monastery, the monks developed a number of stories and manuscripts, went to chapter meetings, underwent penitential rituals, made architectural decisions, set up rules about their clothes, speech, food, guests, and processions, developed discourses, and so forth (their shared repertoire); and they engaged in community maintenance through the production of historiographical and hagiographical texts. Even though the CoP was initially meant to describe (a part of) a present-day company, the high medieval monastery thus fits its mould surprisingly well.

Many other medieval institutions and communities can with equal ease be interpreted within the framework of the CoP, such as guilds, the court, families and clans, or textual communities. Guild members, for example, established norms and relationships between masters and apprentices as they worked together to exchange knowledge and optimize production (mutual engagement), frequently met in their halls to discuss the best ways to maintain or increase the guild’s competitive position within the urban setting and to protect its members (joint enterprise), and developed production methods, rules, laws, and customs while doing so (shared repertoire).

Medieval families kept redefining the relationships between family members and their ‘associates’ while they were managing their business or trying to win optimal marriage partners (mutual engagement), struggled to maintain or enhance their position in society (joint enterprise), and developed their family rituals and repertoires in the process.

Even textual communities could be interpreted within the framework of CoP theory: they emerged because of a joint interest in a ‘text’ or collection of texts and shared information about and interpretations of that ‘text’ (mutual engagement). This joint interest created a shared understanding of their existence as a community (joint enterprise) that subtly changed every time a new member entered the community or whenever there was a shift in the interpretation of the ‘text(s)’ that brought them together. While they were ruminating over the ‘text(s)’ at the heart of their community, they created a repertoire of concepts, discourses, and stories that they used to analyze, understand, and contextualize their central ‘text(s)’.

Horizontal Learning in a Medieval Community of Practice

The CoP profoundly changes the definition of a medieval community and, because of that, the role that horizontal learning had to play within communities.

First of all, the CoP does not focus on one particular element of consensus that it regards as the focal point of the entire community. In the past, attempts to define – for example – a monastic community through a single text or manuscript have all too often led to oversimplifications. Many studies have focused exclusively on texts that were produced as a form of ‘community maintenance’, which were taken at face value as a reflection of ‘the’ identity of ‘the’ community. Yet CoP theory indicates that as the community is inherently heterogeneous, such texts and manuscripts may have been conscious attempts to forge among the community a coherence that it lacked.

Even more important, the message of the studied texts and manuscripts may have been far more ambiguous than has often been thought. For example, I have examined an eleventh-century manuscript that was consciously speaking to various sub-communities within the monastery at the same time and even gave them contradictory messages about their shared patron saint.103 This manuscript was thus not a simple tool to create a collective identity but a heterogeneous discussion item in a complex process of negotiation over the monastery’s joint enterprise.

Second, the CoP approach allows investigating the ‘soft’, subtle, and protean forms of knowledge that together form the community’s repertoire. It underlines that the members of a monastic community based their communal identity not solely on ‘texts’ but also on liturgical performances, the alternation of speaking, keeping silent, and using specific sign language, memories, teaching and fasting, working and praying. Even more importantly, it approaches these ‘soft’ forms of knowledge as items that do not stand on their own but function as part of a repertoire.

Third, older theories of community formation tend to reify the community and overestimate its overall stability. In contrast, the CoP is defined as inherently flexible and unstable, if only because people constantly move in and out of the community.104 As a result, CoP theory emphasizes the need to study how social groups developed over time. In a monastery, recruits entered through the noviciate, old and sick monks died, and various monks left their monastery to find shelter in competing institutions, either because they fled their old house or because their talents were such that they were requested to assist some house in need.105 CoP theory thus has the advantage of encouraging an explicitly diachronic approach when studying communities and the development of communal identities.

Fourth, in this flexible context, members could participate in the community according to their status and capabilities. They usually ascended from a peripheral status vis à vis the group – like a novice in a monastery – to complete participation in its practices, although in most communities it was entirely possible to remain a peripheral participant for life. New members did not have to agree with and become fluent in some codification of a collective memory and identity, but they did have to engage in the process of becoming and remaining a member of the community at their level of expertise. Not everyone had to perform actions at the same level of practice to be valuable members of the community.

Lastly, the members of a community were all rooted in specific biographies.106 Their individuality could lead to struggles within the community to control aspects of practice, as well as attempts to regulate entry and exit.107 Monks clashed over attempted reforms, rewrote manuscripts and stories, and wrestled with newcomers.108 Instead of presuming that a community is inherently consensus-based, CoP theory thus places the community between stability and conflict, which increases our understanding of the dynamics of medieval social groups.

In a monastic context, horizontal learning can be understood as the process of gaining increased familiarity with the performances, rituals, and conventions that together formed the community’s repertoire. However, it did not stop there, for the learners also made active contributions to their subject material. A novice who learned to write, for example, would eventually show his mastery by producing a new manuscript – say, a copy of some exciting new tropes to liven up the liturgical services. That new manuscript subtly changed the community’s liturgical repertoire, and the other monks would have had to learn the tropes if they wanted to perform them in the liturgy. Perhaps the tropes even changed the community members’ understanding of their joint enterprise: the exasperated monks may have decided that they would henceforth ban the singing of these overly musical and exuberant tropes and instead pride themselves on the austerity of their community.109

In short, horizontal learning within dynamic communities was much more than an efficient way to become up-to-date with the community’s conventions and memories, as a necessary prelude to becoming a full community member. Instead, the practice of learning was in and of itself a way to change the community’s repertoire, to become involved in the community’s internal discussions, and thereby to become a full member of the community.

Conclusion

The definition of ‘community’ thus fundamentally determines how we think about horizontal learning. If the community is defined as a relatively stable social group, with few internal conflicts over issues that are truly important to the group as a whole, horizontal learning comes down to the process of socializing newcomers into a settled social group – think of farm boys who learn from their peers how to sow, harvest, and flirt in the appropriate manner.

If communities are seen as entities that were in constant f lux, and in which consensus was a form of power to be fought over, horizontal learning was a tool in the identity battles between social groups. It introduced newcomers to the views that set ‘us’ apart from ‘them’ in political factions, religious groups, and so on.

If, finally, communities are defined as the result of continuous interactions between people who all strive for the continued existence of their community, horizontal learning can be understood as a form of interaction that took place on all levels of the community and created the repertoire, joint enterprise, and mutual engagement of that community. From this point of view, horizontal learning was much more than a way of socializing members into a social group; it was a primary way of constituting the community itself.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Chapter 2 (17-46) from Horizontal Learning in the High Middle Ages: Peer-to-Peer Knowledge Transfer in Religious Communities, edited by Micol Long, Tjamke Snijders, and Steven Vanderputten (Amsterdam University Press, 07.19.2019), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported license.