Rejecting Athenian hegemony.

By Dr. Joshua P. Nudell

Assistant Professor of History

Truman State University

Introduction

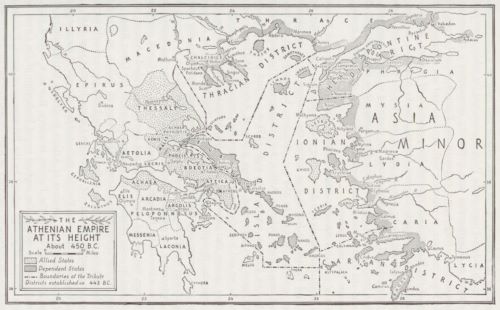

Athenian control over Ionia crumbled close on the heels of the disaster in Sicily. Diodorus Siculus connects the two developments, saying that the failure created contempt for Athenian hegemony (τὴν ἡγεμονίαν αὐτῶν καταφρονηθῆναι, 13.34.1). However, the unraveling of Athenian power had multiple causes. While Diodorus intimates that the Chians, Samians, Byzantines and others had a nearly primal sense of Athenian weakness, the defeat in Sicily had also sacrificed their men and ships for what is presented in our sources as Athenian ambition. At the same time, Athens increased the financial burden on the league through the imposition of the harbor tax, which, John Hyland has recently argued, led to a change in Persian imperial policy to reclaim the tribute from Ionia that had, at least tacitly, been granted to Athens.1

These conditions seem to support Thucydides’ framing, that the Ionians were primed (ἑτοῖμοι) to reject Athenian hegemony when presented with the opportunity (8.2.2). Scholars have traditionally followed this interpretation, based both on the earlier challenges to Athenian rule and because we know the outcome: the Ionians did break away from Athens.2 The question is, what happened?

This article examines how Ionia became disentangled from Athenian hegemony only to be caught up in a convoluted snarl of rapidly changing power relationships in the eastern Aegean that continued until the King’s Peace brought them to a sudden halt in 386. The Ionian War also marked a change in how Ionia interacted with imperial powers.3 For the next quarter century the Ionian poleis oscillated between allegiances as the strength and interest of the competing powers waxed and waned, usually for reasons entirely separate from the machinations over Ionia. In this period, Ionia was a setting for military campaigns designed to reclaim the Ionians as subjects or that used the region as a beachhead to reach another enemy, and ambitious men set their sights on the Ionian cities, once again making the region a cornerstone of the Aegean system.

Contempt for Athenian Hegemony

In 412, an embassy arrived in Sparta (Thuc. 8.5.4). The ambassadors included representatives of the Persian satrap Tissaphernes and conspirators from Chios and Erythrae.4 In a reprise of the start of the Ionian revolt of 499 (Hdt. 5.39–41, 49–51), these Ionians intended to draw the Spartans into a war in Asia Minor, but, bypassing the king Agis at Decelea, they went directly to Sparta. Once there, though, they discovered that the real challenge was not inciting the Spartans to action but persuading them to sail to Ionia. At about the same time, Calligeitus of Megara and Timagoras of Cyzicus had come to Sparta on behalf of Pharnabazus, another Persian satrap (Thuc. 8.6.1).5

The two embassies made the same argument: support the liberation of the eastern Aegean and join with Persia because it will cripple Athens. The critical difference was the destination of the campaign, the Hellespont or Ionia. Choosing Pharnabazus and the Hellespontine Greeks would have severed the Athenian lifeline, the trade route that brought grain from the Black Sea, and Pharnabazus’ emissaries brought with them a sweetener of twenty-five talents (Thuc. 8.8.1). A campaign in Ionia did not offer such immediate rewards. The Chians, however, talked up the strength of their fleet in order to demonstrate their importance to the Athenian war effort. The Spartans were still skeptical, according to Thucydides, but the Ionians had the support of Alcibiades and, through him, the ephor Endius (8.6.3; 8.12).6 Rather than rushing into action, the Spartans discretely dispatched Phrynis, a perioikos, to reconnoiter and discover whether the Chians were exaggerating their strength (Thuc. 8.6.4). Satisfied with the report in the summer of 412, the Spartans agreed to send Chalcideus in command of a fleet and with Alcibiades in tow.

Haste was of the utmost importance, despite the delay. The Chians had traveled in secret, and every additional day increased the risk of discovery. The expedition, however, required conveying ships across the isthmus of Corinth, which would have required the Corinthians to violate the Isthmian truce, and they simply refused. It was during this final delay, when their representatives to the Isthmian games saw preparations for an expedition (Thuc. 8.10.1), that the Athenians became suspicious (Thuc. 8.9.2). They sent the general Aristagoras to Chios with accusations of treachery. Most of the Chians had no knowledge of the plot, and the conspirators, whom Thucydides describes as the few in the know (οἱ δὲ ὀλίγοι καὶ ξυνειδότες), were unwilling to act without Spartan support, so they roundly denied the accusations and agreed to send seven ships to join the Athenian fleet as a demonstration of good faith (8.9.2–3).

Their initial efforts were thwarted by Athenian blockades, but the Spartans persisted, and the fleet eventually arrived in Ionia. At the behest of the Chian conspirators, they sailed directly into the town of Chios, where the council was in session. Chalcideus and Alcibiades, Thucydides says, gave speeches to the assembled Chians and, with the promise of more Peloponnesian ships on the way, persuaded them to revolt from Athens before doing the same in Erythrae and Clazomenae (Thuc. 8.14.2–4). The revolutions in Ionia unfolded quickly, but this is not necessarily a sign of popularity. The Spartans remained suspicious of the Chian resolve, and probably for good reason since the rebellion had been carried out through a conspiracy that circumvented any popular opposition.7 Since the Chians were also more experienced sailors than his Peloponnesians, Chalcideus elected to kill two birds with one stone by forcing the Chians to man his ships while arming his Peloponnesians and leaving them behind on the island as a garrison (8.17.2).

The Athenians responded swiftly by recalling the seven Chian ships, arresting the free crews on the charge of being involved in the conspiracy, and emancipating the enslaved rowers (Thuc. 8.15.2). The Athenians then authorized up to forty-nine warships to be sent to Ionia in the hopes of turning public opinion again before the dominoes all fell.

What followed was a period of moves and countermoves during which Ionia was up for grabs. The first Athenian squadron, eight ships under the command of Strombichides, arrived at Samos and tried to interrupt the cascade by sailing on to Teos (8.16.1). Their arrival, Thucydides says, at first had the intended effect on the Teians, who closed their gates against the Erythraean and Clazomenaean infantry who had arrived by land (8.16.1). When Chalcideus arrived from Chios with his twenty-three ships, Strombichides put to sea and was chased back toward Samos. Deprived of Athenian support, Teos capitulated and the Erythraeans, Clazomenaeans, and mercenaries in Tissaphernes’ pay began to dismantle the walls (Thuc. 8.16.3). Chalcideus and Alcibiades sailed next from Chios to Miletus, their fleet reinforced with twenty ships from Chios, arriving just ahead of two Athenian squadrons under Strombichides and Thrasycles (Thuc. 8.17.2–3). Alcibiades had a family connection to influential Milesians and therefore believed that he would be able to induce a revolt and thereby claim credit for winning the war (Thuc. 8.17.1).8 Failing to intercept the Peloponnesians, the Athenians established a blockade of Miletus from the island of Lade until reinforced by thirty-five hundred additional troops under the command of three generals, Phrynicus, Onomacles, and Scironides (Thuc. 8.17.3, 24.1).9 The subsequent battle between this Athenian force and combined forces of Miletus, Tissaphernes, and a handful of Peloponnesians ended in a draw, with Thucydides noting that each sides’ ethnic Ionians triumphed over the ethnic Dorians (8.25.5). Despite being prepared to besiege Miletus, the Athenian forces withdrew when a larger Peloponnesian fleet threatened to cut them off from their allies (8.27).10 Other Chian ships fomenting rebellion in Ionia were less fortunate and took refuge in Ephesus and Teos when they ran into Athenian reinforcements.

But what did the Ionians think of this turn of events? It is a common position of modern historiography that the Ionians invariably turned away from Athens out of a desire to restore their liberty lost in the development of the Athenian empire.11 This position, however, fails to appreciate the complexities of the Ionian polities and the role of regional interactions. Thucydides’ narrative for the outbreak of the Ionian War makes it clear that the Ionians were anything but of one mind. At Chios, the people conspiring to use Sparta and Persia as counterweights to Athens were not doing so from exile, but as prominent members of the community who arranged for the boule to meet just when Endius and Alcibiades arrived (Thuc. 8.14.1–2). In Thucydides’ telling, more-over, the general population was hesitant to make a rash move, but also was not set against the idea. Most other Ionian poleis did not play as active a role, but between dissatisfaction with Athens and the threat of force from Sparta, Persia, and their fellow Ionians, the choice was easy. And yet the situation was not irreversible. At Erythrae, a particularly decentralized polis, Athenian vessels con-tinued to use Sidoussa and Pteleum as bases from which to harass Chios (Thuc. 8.24.2). When the Athenian commander Diomedon arrived at Teos sometime after its walls were demolished, the citizens received him and offered to rejoin Athens (Thuc. 8.20.2). Similarly, when Athenian forces captured a fort at Polichna and forced the men who caused the revolt at Clazomenae to flee (τῶν αἰτίων τῆς ἀποστάσεως), the city reverted to Athens (Thuc. 8.23.6). In the end, almost every polis in Ionia left the Athenian orbit, but this brief survey reveals considerable reticence already in 411/0. Far from a popular uprising against tyrannical Athenian overreach, this was a rebellion that broke out in fits and starts, complicated by long-standing internal tensions and the threat of force.

The lone Ionian polis never to abandon Athens was Samos, which served as the primary Athenian outpost in the eastern Aegean for the remainder of the war. But neither was Samos exempted from the schisms erupting throughout the region. Diodorus includes Samos in the list of poleis that felt contempt at Athenian hegemony (13.34.1), and its leadership in 411 was suspected of plotting with Sparta, as had happened in Chios. The result was a brutal coup. The demos took it upon itself to overthrow the men in power, summarily executing two hundred and sending another four hundred into exile after confiscating their property (Thuc. 8.21; cf. Xen. Hell. 2.2.6). Later in 411, the Samian demos with Athenian military aid defeated an attempted countercoup carried out by three hundred oligarchic conspirators, executing thirty more and banishing three ringleaders. When he heard about the factionalism on Samos, the Spartan navarch sensed an opportunity to appease discontents within his own ranks by making an assault on the island. He launched his entire fleet and instructed the Milesians to meet them on the Mycale promontory across from Samos, but a brief show of force from the Athenian fleet and reinforcements from the Hellespont prompted him to withdraw without offering battle (Thuc. 8.78–79).

Some modern scholars look at these events on Samos as a constitutional crisis between oligarchs and democrats, but it is reductive to treat it exclusively in these terms.12 The conflict as described by Thucydides was along class lines, with the poor strata of society overthrowing the ruling landowners and instituting new laws to deprive them of their position, which, in turn created new schisms within the Samian state (Thuc. 8.73).13 But equally important was the orientation of Samos toward Athens and Sparta.14 Since 439 and as late as 412, the authorities in Samos had been in step with Athens to maintain leverage against the exiles at Anaea. This situation had preserved a status quo for more than a quarter century, but as Athenian power in Ionia waned, the ruling class on Samos considered seeking Spartan support toward the same end. Unlike on Chios, where the presence of Spartan ships and the honeyed tongue of Alcibiades persuaded the citizen body to abandon Athens, popular sentiment on Samos, supported by three Athenian ships, ran the other way. The result was a bloody purge that Thucydides says the Athenians took as a sign of loyalty. They legitimized the new leadership and sent the fleet to the island to ensure that it remained in the Athenian orbit.

The Spartan decision to precipitate a general uprising in Ionia paid off. The Chians, in particular, threw themselves into the Spartan venture, even sending an expedition of their own ships to Lesbos to incite a revolution there (Thuc. 8.22.1). The response was more muted, even tepid, elsewhere in Ionia, but nei-ther was resistance stiff except on Samos, which remained an Athenian ally to the bitter end.

Battlefield Ionia

After the initial wave of revolutions in 411 and 410 Ionia became a battlefield. The conflict between Athens and Sparta took center stage in this development, but the situation was rarely that simple. Already in 412/1, Tissaphernes began to recover Persian suzerainty over Ionia by building and garrisoning a fort in Milesian territory, which may have been interpreted as a precursor to a regime change (Thuc. 8.84.4).15 Outraged, the Milesians drove the Persian forces out, to the acclaim of their Greek allies—except Sparta.16 The Spartan commander in Miletus, Lichas, chastised them, saying that because they lived in Persian territory, they ought to obey the satrap (τε χρῆναι Τισσαφέρνει καὶ δουλεύειν Μιλησίους καὶ τοὺς ἄλλους τοὺς ἐν τῇ βασιλέως τὰ μέτρια καὶ ἐπιθεραπεύειν, Thuc. 8.84.5).17

Lichas’ admonition followed official Spartan policy based on the treaty established in 411. Although never ratified, the first iteration of the treaty negotiated between Chalcideus and Tissaphernes framed terms of debate. According to Thucydides, this agreement read (8.18):

Whatever land and cities the king has and that the ancestors of the king had are the king’s. And whatever money or other profit came to the Athenians from these cities, the king and the Lacedaemonians and their allies together shall intercept, such that the Athenians receive neither money nor anything else. The king, the Lacedaemonians, and their allies shall wage war in tandem against the Athenians. . . . Should any [poleis] revolt from the king, then they are enemies of the Lacedaemonians and their allies; and if any revolt from the Spartans and their allies, they are enemies to the king.

ὁπόσην χώραν καὶ πόλεις βασιλεὺς ἔχει καὶ οἱ πατέρες οἱ βασιλέως εἶχον, βασιλέως ἔστω: καὶ ἐκ τούτων τῶν πόλεων ὁπόσα Ἀθηναίοις ἐφοίτα χρήματα ἢ ἄλλο τι, κωλυόντων κοινῇ βασιλεὺς καὶ Λακεδαιμόνιοι καὶ οἱ ξύμμαχοι ὅπως μήτε χρήματα λαμβάνωσιν Ἀθηναῖοι μήτε ἄλλο μηδέν. καὶ τὸν πόλεμον τὸν πρὸς Ἀθηναίους κοινῇ πολεμούντων βασιλεὺς καὶ Λακεδαιμόνιοι καὶ οἱ ξύμμαχοι . . . ἢν δέ τινες ἀφιστῶνται ἀπὸ βασιλέως, πολέμιοι ὄντων καὶ Λακεδαιμονίοις καὶ τοῖς ξυμμάχοις: καὶ ἤν τινες ἀφιστῶνται ἀπὸ Λακεδαιμονίων καὶ τῶν ξυμμάχων, πολέμιοι ὄντων βασιλεῖ κατὰ ταὐτά.

Delegates revised this agreement the following year, adding provisions that forbade the Spartans from collecting tribute from the territory belonging to the king, thereby making them more reliant on Persian patronage. The new language that explicitly prevented the Spartans and their allied forces from attacking Persian domains testifies as much to the strained relationships between the Peloponnesian forces and the Persians as it does to their acquiescence that Ionia now belonged to Persia.18 Following a topos in fourth-century Athenian rhetoric, modern treatments of these treaties often focus on whether Sparta sold out the Ionians in its haste to defeat Athens.19 Compounding this interpretation is the implication found in Thucydides that, for as much as the Spartans conceded, Tissaphernes was unprepared to hold up the Persian side of the bargain (Thuc. 8.59; 87). John Hyland has recently reexamined these treaties, showing that they reflect the standard expression of a benevolent, just, and exacting king now reclaiming territory that was rightfully his.20 There are ultimately no grounds to vilify the Spartans for betraying the Ionians to Persia with this treaty because their motivation for inciting revolts in 411 was to cripple Athens, not to liberate Ionia. As was often the case, declarations of freedom were little more than hollow-point rounds in a weapon aimed at another target. However, as the example from Miletus demonstrates, this does not mean that the Ionian poleis were without a role to play.

As Sparta and Persia negotiated these treaties, Athenian squadrons sent to Lesbos under the command of Diomedon attacked a fort at Clazomenae (8.23.6) and proceeded to raid Chios (8.24.2–3). They defeated the Chians in three battles on the island, and the Chians afterward refused to give battle. This occasion prompted Thucydides to provide a eulogy for the prudent decision-making that had made Chios wealthy (8.24.4–5).21 His praise falls immediately after a description of the spoliation of the countryside, implying that the economic complications stemmed from agricultural devastation. However, although repeated attacks shattered any sense of inviolability, the more severe consequences came from the disruption of trade routes and the loss of their enslaved people after the Athenians fortified Delphinium on the north side of the island (Thuc. 8.40).22 These reverses strained the relationship with Sparta, and some in Chios entertained second opinions about the wisdom of their choice. When the men who had led Chios into revolt caught wind of a conspiracy against Sparta and, by extension, against them, they summoned aid from the Spartan navarch Astyochus. According to Thucydides, Astyochus tried to resolve the conflict with minimal bloodshed by taking hostages (8.24–25), but the situation continued to deteriorate.23 Their plight was also complicated by the relationship between Astyochus and the harmost Pedaritus, who kept Chios in line with a reign of terror. Pedaritus executed one Tydeus, a leading citizen and possibly the son of the poet Ion, allegedly for conspiring to restore the Athenian alliance (Thuc. 8.38).24 When Astyochus ordered the Chians to send ships to Lesbos to encourage rebellions on that island, Pedaritus informed him that none would go (Thuc. 8.32.3). Despite Pedaritus’ intervention, Astyochus nevertheless blamed the Chians, repeatedly threatening them that he would not come to their aid should they ever require it (8.33.1). When some Chians expressed a lack of confidence in their forces and Pedaritus’ mercenaries to protect the polis after Athenian reinforcements landed on the island, Astyochus was good to his word (Thuc. 8.38).

Regional tensions also continued to influence Ionian behavior. When Athenian forces under the command of Thrasyllus besieged Pygela, a small community that had once been dominated by Ephesus, it was Milesian hoplites who came to their relief. The two hundred Milesian hoplites chased the scattered Athenian light troops upon arriving at the scene but were almost entirely wiped out when confronted by a contingent of Athenian peltasts and hoplites (Xen. Hell. 1.2.2–3; Diod. 13.64). Despite some attempts to use this episode to deride the military capacities of the Milesians,25 disciplined peltasts posed a particular threat to hoplites, and it is probable that the Milesians were both outnumbered and disorganized, having pursued the first Athenians they came upon.26 From a military perspective the more important question is why relief came from so far away.27 The answer lies in the regional politics of Ionia. The Milesian hop-lites were two or three days’ march from home when they clashed with Thrasyllus’ forces, but requesting help from Ephesus would have given it an open-ing to recapture its erstwhile dependent, something it would repeatedly aspire to in the fourth century, leading the Pygelans to use Miletus and Mausolus of Caria as a counterweight to Ephesian ambitions.28 As John Lee characterizes it: “Thrasyllus had hit a weak spot in Tissaphernes’ defenses, where local politics trumped military practicalities.”29 Almost all of the Ionians might have sided with Sparta, but this did not mean that they were on each other’s side.

The anti-Athenian forces ultimately defeated Thrasyllus at the foot of Mount Coressus, just outside of Ephesus. However, while the Ephesians contributed to their own defense and subsequently awarded honors to the Syracusans and Selinuntines whose ships were stationed at Ephesus at the time (Xen. Hell. 1.2.10), the bulk of the credit for the victory belonged to Tissaphernes. When the satrap heard that Thrasyllus was planning a return to Ephesus, Xenophon says, Tissaphernes mustered his forces with the rallying cry to defend the sanctuary of Artemis (Xen. Hell. 1.2.6–10). The sanctuary was a natural focal point for this effort given its regional prominence, and Tissaphernes capitalized on the victory with a series of bronze coins that included an image of Artemis.30 Unlike at Miletus, Tissaphernes did not attempt to install a garrison at Ephesus. Lee reasonably explains his decision as a calculation that protecting a local religious institution would be more effective at securing loyalty than would a garrison, but this also allowed him to maintain maximum flexibility to respond to Athenian hit-and-run raids in a theater characterized by multiple river valleys.31 Although Lee is correct that Tissaphernes’ deft touch at Ephesus ruffled fewer feathers than at Miletus, Xenophon offers no indication that his defense of Artemis and Ephesus won him any affection from the citizens.

The situation in Ionia began to change in 408 when Sparta ratified a new treaty that set the terms for cooperation in the war against Athens (Xen. Hell. 1.4.2–3). In the wake of the treaty, Darius II appointed his son Cyrus as karanosover western Anatolia, a position akin the Greek strategos. This office gave the prince broad powers to oversee the war effort that to this point had been limited by competition between Tissaphernes and Pharnabazus (Xen. Hell. 1.4.3, 5.3; cf. Anab. 1.9.7).32 According to Xenophon, Cyrus arrived in Asia Minor bearing the king’s seal stamped on a letter addressed to all “those who dwell by the sea” (πάντων τῶν ἐπὶ θαλάττῃ, Xen. Hell. 1.4.3), which certainly included the Ionians. It is unknown whether the letter addressed specific actions or the renewed status of Ionia as subjects of Persia because Xenophon only preserves part of the text. Tissaphernes had, to the Greeks at least, coordinated the war against Athens piecemeal, on his own terms, and always with a sense that he anticipated that if Athens and Sparta exhausted each other, it would further his position. Certainly, these were the charges the Spartans leveled against Tissa-phernes when Cyrus arrived (e.g., Plut. Lys. 4.1). However, it was the resources available to Cyrus, not the attitude toward the Ionian poleis or relationship between the poleis and the Persian satrap, that changed. Greek authors ascribe a cunning malice to Tissaphernes, but with respect to Ionia he was following orders.33 His methods aroused more enmity than did Cyrus’ flattery, but the expectation of the Great King throughout the fifth century had been that he was sovereign over Ionia. Accommodations about revenue could be made to support the Spartan war effort, and the treaty negotiated in 408 was aimed at this end, not toward securing new freedoms for the Ionians. But the war over Ionia was entering a new phase in 408, one powered by the personality of the new Spartan navarch, Lysander.

Enter Lysander

Lysander took command of the Spartan war effort in Ionia in autumn 408, initiating wide-ranging changes in the region that would shape its history for a decade. One of his first actions was to move the Spartan base of operations from Miletus to Ephesus (Plut. Lys. 3.2). Plutarch makes a big deal about the move because he claims that Lysander rescued Ephesus from barbarity, but this is exaggerated.34 The absence of a Persian garrison might have contributed to Lysander’s decision, but other considerations were likely more important. Miletus was the southernmost Ionian city and was separated from the other centers of Spartan activity by the Athenian fleet on Samos. Ephesus neatly sidestepped a repeat of 411, when Lichas ordered the Milesians to accommodate Tissaphernes, but it also put the Spartan fleet in a better position to counter Athenian activities. More important, though, and critical for the history of Ionia, was the close connection between Ephesus and Sardis, where the Persian prince Cyrus had recently taken up residence. With these regional and strategic considerations in mind, Lysander assembled the Spartan fleet at Ephesus.

Lysander’s primary concern when he assumed command was to secure a steady supply of money to pay for the naval war. John Hyland has recently estimated the Persian subsidy, including direct payments and the Ionian tribute remitted in 405/4, at between 3,272 and 3,672 talents over the course of roughly seven years.35 These resources, in turn, allowed Lysander to inaugurate a massive stimulus project at Ephesus that brought merchant vessels to convey sup-plies to the city and dispensed contracts for trireme construction (Plut. Lys. 3.3). Even absent the remission of tribute, these contracts brought an infusion of wealth to Ephesus that likely lay behind an honorific statue erected at the Artemisium (Paus. 6.3.15).36

However, Persian money proved unreliable, which led to Spartan demands that the Ionians themselves underwrite the costs of the fleet. In turn, these demands reignited preexisting tensions.37 Already in 411, for instance, the Spartan navarch Mindaros demanded that the Chians pay each of his sailors three “fortieths” (Thuc. 8.101.1), an amount that totaled about 4.5 talents,38 and the demands for cash steadily grew as the war dragged on. In 408/7, Diodorus reports, the Spartan navarch Cratesippidas took a bribe to restore Chian exiles to their home, where they exiled six hundred of their political opponents in turn (Diod. 13.65.3–4). The new exiles seized Atarneus, from whence they continued to harass Chios. But these strains also extended beyond the endemic factional conflict and further drained Ionian resources. Lysander’s immediate successor after his first term as navarch, Callicratidas, convinced the people of both Miletus and Chios in 406/5 to give him additional money when he thought that Cyrus was balking at providing what he promised (Xen. Hell. 1.6).39 Xenophon says that he demanded from Chios a pentedrachmia (πεντεδραχμία) for each of his sailors, probably about 23.1 talents of silver in sum, that would pay the wages for just ten days (Xen. Hell. 1.6.12).40 The soldiers serving under the Spartan Eteonicus had been forced to work for hire in the winter of 406, but they subsequently planned a coup against their supposed ally when the seasonal employment dried up (Xen. Hell. 2.1.1–5).41 Eteonicus thwarted their plan and restored discipline, but also demanded that the Chians give him up to some fifty talents of silver to appease the soldiers.42 The Chians paid up, but they also joined the other Ionian allies to formally petition Sparta for Lysander’s return (Xen. Hell. 2.1.6–7)

The Spartans had entered the war against Athens woefully ignorant about how much money was required to operate a fleet and about the mechanisms of finance. Recent research has demonstrated how their approach to financing the war both slowly evolved over the course of the conflict and ultimately allowed them to eventually emerge triumphant.43 By the time that Lysander returned in 405/4, the Spartan fiscal system had reached maturity, funneling Persian subsidies, ad hoc requisitions from allied poleis, and the tributes from Persian subjects in Asia Minor (Xen. Hell. 2.1.14) into pay for the maintenance, upkeep, and operation of fleets throughout the Aegean. The enforcement of this system resulted in the widespread adoption of the Chian weight standard to facilitate conversion between the coinages of different poleis and the so-called ΣΥΝ coinage minted at Rhodes, Iasus, Cnidus, Ephesus, Samos, Byzantium, and Cyzicus.44

But where did these changes leave the Ionians? The second century CE travel writer Pausanias records an Ionian proverb about their political loyalties saying that they preferred to “paint both sides of the walls” because “the Ionians, just like all men, do service to strength” (τοὺς τοίχους τοὺς δύο ἐπαλείφοντες . . . καὶ Ἴωσιν ὡσαύτως οἱ πάντες ἄνθρωποι θεραπεύουσι τὰ ὑπερέχοντα τῇ ἰσχύι, 6.3.15–16). They paid court to Alcibiades, he says, with the Samians erecting a statue of him in the Heraion, as easily as they did to the Spartans, since the Ephesians erected statues not only of Lysander, Eteonicus, and Pharax, but also of Spartans of no particular repute! Indeed, there is little unambiguous evidence that the Ionians as a whole favored one side over the other, which fits in a world where nobody was altogether on the side of the Ionians. These statues therefore need to be interpreted as early examples of honorific statues that became a prominent feature of diplomacy in the Hellenistic period, while paying court was the surest way to minimize property damage. Spontaneous displays of support for the war against Athens disappeared after the first years, and poleis without strategic importance had been allowed to slip from Spartan control. Teos, for instance, which had lost its walls in 411, had subsequently readmitted Athenian forces, ostensibly in return for protection (Thuc. 8.20), only to see Callicratidas sneak his forces inside the restored fortifications and plunder the city in 406/5 (Diod. 13.76.4). Being forced to turn over increasingly large sums of money for the Spartan war efforts could not have been popular, but neither those demands nor the fact that the Spartans symbolically curtailed Ionian liberty by betraying them to Persia resulted in widespread uprisings and Ionian ships and sailors remained essential to the Spartan fleets throughout the war (e.g., Xen. Hell. 1.6.3; Diod. 13.70.2).45 When Lysander erected an ostentatious monument at Delphi to commemorate his victory at Aegospotamoi, he paid tribute to these contributions with statues of not only three Chians, but also men from Ephesus, Miletus, a Samian from Anaea, and likely an Erythraean (Paus. 10.9.9)— nearly a quarter of the twenty-nine naval commanders honored in the monument, in all.46

By the last years of the Ionian War only Samos and pockets of Athenian-held territory resisted the overwhelming tide of Spartan successes. It is easy see an element of coercion in this continued resistance since Samos continued to be the principal Athenian naval base in the eastern Aegean, but this was not the only reason that Samos continued to fight alongside Athens. Xenophon associates the Samian loyalty to Athens with fact that they had enacted a slaughter of the wealthy on the island (σφαγὰς τῶν γνωρίμων ποιήσαντες) when those men had conspired to revolt (Hell. 2.2.6). The Samian demos had clearly wanted to keep its relationship with Athens and in 405/4 were rewarded en masse for their dedication with a decree of Athenian citizenship (RO 2 = IG I3 127, ll. 12–13), as well as receiving other honors and gifts, including the Athenian triremes on Samos (ll. 25–26).47 There was, however, another reason that the Samians looked to Athens. The Samian exiles living in Asia Minor make frequent appearance throughout the fifth century, including sending ten ships to fight with the Spartans at Arginousae (Xen. Hell. 1.6.29). Thucydides and Xenophon present the bloodshed on Samos as a class conflict caused by the question of loyalty to Athens, but this was only the proximate cause. These exiles were the root of the conflict.

Samos continued to hold out against Sparta after the battle of Aegospotamoi in 405 (Xen. Hell. 2.2.6, 3.6) and the fall of Athens in 404, surrendering only in 403 after a long siege (Xen. Hell. 2.3.6–7). The long resistance may have worsened Lysander’s punishment of the Samians, but his actions nonetheless capture the new status of Ionia. Lysander returned the exiles to power, as well as installing a Spartan named Thorax as harmost, stationing a garrison on the island, and appointing a narrow oligarchy (Xen. Hell. 2.3.6–7).48 These arrangements also created a new wave of exiles, many of whom probably went to Athens, while others sought refuge nearby in poleis such as Ephesus and Notium (RO 2 = IG I3 127, ll. 49–50). On top of paying the Spartan war tax, the restored Samians offered ostentatious honors for Lysander, including a statue of him at Olympia erected at public expense (Paus. 6.3.14–15), couplets from poet Ion of Samos decorating his victory monument at Delphi (ML 95 = SEG 23.324b) and renaming the festival for Hera the “Lysandreia” (Duris, BNJ 76 F 26).49 The festival occurred under this name at least four times, probably only being abolished in 394 after the battle of Cnidus. While Lysander was unsuccessful in persuading the poet Choerilus of Samos to compose an epic poem about his triumphs (Plut. Lys. 18.4), multiple winners of the poetic competitions at the Lysandreia took up the theme of his greatness.50 It was in this context that Duris of Samos says that the Samians dedicated altars and a cult to Lysander as though he were a god (BNJ 76 F 71).51 While honorific statues became a normal diplomatic practice, the creation of the Lysandreia was likely indicative of more sinister processes at work.

The Spartan victory in 404 made Lysander arguably the most powerful man in the Aegean world, and our surviving sources suggest that he had been pre-paring for this moment since 407. According to one of these sources, Lysander summoned oligarchic-minded men to Ephesus, instructing them to form hetaireia in their communities and to integrate themselves into public affairs with the promise that he would appoint them to what Plutarch calls “revolutionary decarchies” (γενομένων δεκαδαρχιῶν, Lys. 5.3–4; cf. Diod. 13.70.4). Thus, it is thought, Lysander cultivated supporters who would be loyal to him and used them as a seed to create a system of decarchies throughout the Aegean in 404/3.52 However, this tradition is riddled with source problems. The only polis in Ionia where we know that Lysander established a decarchy was Samos, which had remained allied with Athens throughout the war and thus was likely regarded as particularly suspect, though Chios, which lay outside of Persian territory, likely had one as well. Moreover, hetaireia were a normal part of elite Greek life even in the most radical of democratic poleis, so it is implausible that Lysander himself introduced a substantial, widespread change in Ionia. This is not to say either that Lysander did not build close relationships with Ionian aristocrats or that he did not support these allies in overthrowing what remained of the popular governments in Ionia (Plut. Lys. 7.2). Rather, this was a negotiated and reciprocal relationship that he never formalized on a wide scale.53 Lysander’s generosity won him allies who chaffed at Callicratidas’ frugality and therefore requested his reappointment.

Exemplary of these political currents was a particularly brutal coup at Miletus in c.405. According to Diodorus, events transpired as follows (13.104.5–6):

At the same time in Miletus certain men with oligarchic proclivities dissolved the demos with Spartan aid. First, during the Dionysia, they abducted their principal opponents from their homes and slit the throat of some forty men; then, after that, when the agora was full, they killed three hundred chosen for their wealth. The most accomplished of those who favored the demos, who numbered not fewer than a thousand, fled to the satrap [Tissaphernes]54 because they feared their situation. He received them generously, giving each a stater and settling them in Blaudos,55 a citadel in Lydia.

καθ ̓ ὃν δὴ χρόνον ἐν τῇ Μιλήτῳ τινὲς ὀλιγαρχίας ὀρεγόμενοι κατέλυσαν τὸν δῆμον, συμπραξάντων αὐτοῖς Λακεδαιμονίων. καὶ τὸ μὲν πρῶτον Διονυσίων ὄντων ἐν ταῖς οἰκίαις τοὺς μάλιστα ἀντιπράττοντας συνήρπασαν καὶ περὶ τεσσαράκοντα ὄντας ἀπέσφαξαν, μετὰ δέ, τῆς ἀγορᾶς πληθούσης, τριακοσίους ἐπιλέξαντες τοὺς εὐπορωτάτους ἀνεῖλον. οἱ δὲ χαριέστατοι τῶν τὰ τοῦ δήμου φρονούντων, ὄντες οὐκ ἐλάττους χιλίων, φοβηθέντες τὴν περίστασιν ἔφυγον πρὸς Φαρνάβαζον τὸν σατράπην. οὗτος δὲ φιλοφρόνως αὐτοὺς δεχάμενος, καὶ στατῆρα χρυσοῦν ἑκάστῳ δωρησάμενος, κατῴκισεν εἰς Βλαῦδα, φρούριόν τι τῆς Λυδίας.

Diodorus notes that the conspirators had Spartan backing for their coup, but later traditions tie the entire episode to Lysander specifically, whether through his willingness to lull the people into a false sense of security (Polyaenus 1.45.1) or by saying that he provoked them to action when they seemed prepared to settle with their domestic opponents (Plut. Lys. 8). However, as Vanessa Gorman notes, contemporary sources for this coup, including Xenophon’s account of the period and the Milesian epigraphical record, make no mention of the atrocities—let alone attest to Lysander’s involvement.56 This incongruity creates a problem for understanding Miletus in this period. Oligarchic regimes as a rule did not produce inscriptions for public consumption, and the specificity of detail in Diodorus’ account generally follows the violence of contemporary oligarchic regimes, both of which suggest that the massacre could have taken place. Further, it was followed by another round of exiles just a few years later (see below, “Persian Dynastic Politics”), and there was no democratic reconciliation that would necessitate public acknowledgment of events. At the same time, this is the last that we hear of the exiles at Blaudos specifically—in marked contrast to the exiles from Chios and Samos—and there is no indication of a regime change on the aesymnetes list (Milet I.3, no. 122).57 The coup at Miletus fits the wider context of political restructuring that took place throughout the Aegean, where local oligarchs took advantage of Spartan hegemony to seize power against their populist rivals.58 However, where both Samos and likely Chios were saddled with Spartan harmosts upon the conclusion of the war (Diod. 14.10), there is no evidence for a comparable arrangement on the main-land. Those poleis belonged to Persia.59

Domestic backlash against Lysander’s power ultimately caused the Spartans to withdraw support from his imperial arrangements in 403/2.60 The ephors declared their support for ancestral constitutions in Ionia (Xen. Hell. 3.4.2) and recalled Lysander’s appointed harmosts, ultimately executing Thorax, who held that position at Samos (Plut. Lys. 19.4). Both actions were strikes against the navarch, but we ought to be careful not to overstate how big a change this was in Ionia. The constitutions in question were unlikely to have been democratic, even in poleis with strong democratic traditions, and, regardless of how repugnant these oligarchic regimes were thought to be, there is no evidence that they entirely crumbled in the absence of Spartan support. The Samians for instance, held the Lysandreia for at least two more cycles after Lysander’s recall, while the only documented instance of imminent regime change was not a popular uprising, but an outgrowth of Persian dynastic politics. The change in attitude in Sparta might have prompted a withdrawal from the eastern Aegean following the Peloponnesian War, but it neither caused widespread political upheaval in Ionia nor dissolved the relationships that had been formed.

Persian Dynastic Politics (404-401 BCE)

At the conclusion of the Peloponnesian War in 404, Cyrus and Tissaphernes reasserted Persian control over Ionia.61 Treaties between Sparta and Persia in the preceding years had recognized the legitimacy of Persian authority in return for military and financial support for the war, and the Spartan commander Lichas had chastised the Milesians for asserting their autonomy against Tissaphernes (Thuc. 8.84.5). Cyrus’ arrival in western Anatolia changed the Persian hierarchy by giving him control over multiple existing satrapies (Xen. Hell.1.4.3; Anab. 1.9.7) but did not fundamentally change the relationship between Ionia and Persia.62 For the Ionians, though, this situation was one of limbo. Spartan commanders were generally unwilling to support Ionians against Per-sia, but Lysander also enrolled the Ionians into the Spartan alliance system. When Spartan enthusiasm for projecting power into Asia Minor waned after 404, the Ionian poleis became embroiled in the Persian conflict between Cyrus, Tissaphernes, and, ultimately, Artaxerxes II.

Darius II died in 405/4, elevating Cyrus’ older brother Artaxerxes to the throne. The royal intrigues of Parsyatis, Cyrus, Artaxerxes II, and Tissaphernes and the campaign that culminated in the battle of Cunaxa in 401 are largely beyond the scope of this study, but they need to be addressed in brief since the campaign began in Ionia. Cyrus left Anatolia for a time in 405 before his father died, likely to answer charges that he had overstepped his mandate by executing a member of the Persian nobility (Xen. Hell. 2.1.8). Cyrus was exonerated and, at the behest of their mother, Parsyatis, Artaxerxes II initially reconfirmed his brother’s position. When Tissaphernes accused Cyrus of plotting a coup, Artaxerxes reversed course and had him arrested (Xen. Anab. 1.1.3; Ctesias F 19.59; Plut. Artax. 3.4).63 Parsyatis again intervened to prevent her son’s execution, and Cyrus returned to Sardis, where he began in earnest to plot against his brother. Artaxerxes acknowledged Cyrus’ position in Sardis, but also created a new satrapy for Tissaphernes in Caria, to which he appended the Ionian poleis (Xen. Anab. 1.1.6).64 This situation in western Anatolia was an uneasy post hoc arrangement. The revenues from Ionia belonged to Tissaphernes on paper, but therein lay the rub.

Most Ionian poleis simply ignored Artaxerxes’ order to pay their tribute to Tissaphernes and instead submitted to Cyrus. Their choice was easy. The Ionians undoubtedly mistrusted Tissaphernes based on earlier interactions, while Cyrus entertained them lavishly, promising to remit their tribute should they support his cause. As Hyland notes, Xenophon also glosses over Cyrus’ coercive activities to present the prince in the most positive light (Xen. Anab.1.1.8).65 Only Miletus resisted Cyrus’ charms, and not for want of enticement. When Tissaphernes learned that some Milesians were considering Cyrus’ offer, he seized the city, exiled Cyrus’ supporters, and installed men who would be loyal to him, perhaps by restoring those who had been exiled to Blauda in c.405 (Xen. Anab. 1.1.6–7). Once again, the stark divisions within a citizen body of an Ionian polis entered the realm of imperial politics. The opening move of Cyrus’ anabasis therefore did not entail a march upland at all, but a brief siege of Mile-tus with the stated aim of restoring the exiles. This campaign, however, was a feint, and Cyrus soon abandoned Miletus to embark on his campaign against Artaxerxes (Xen. Anab. 1.2.2).66

Liberation from Athens never actually aimed at an independent Ionia. Rather the intersection of local agendas with Spartan and Persian interests had brought about change. In this same vein, the Ionian ambivalence toward the project that appeared almost as soon as the fighting started can be better explained by the presence of war that most Ionians had no interest in than by dissolution at betrayed promises. The only respite came when events elsewhere meant that the imperial collaborators were too occupied to intervene in Ionia. Cyrus’ quixotic bid for the Persian throne drew both him and Tissaphernes toward the Persian heartland and left Ionia free from Persian intervention for a time. Following Cyrus’ death at Cunaxa in 401, Artaxerxes once more gave Tissaphernes control over Ionia. Xenophon says, unsurprisingly, that the Ionians feared retribution for having sided with Cyrus (Xen. Hell. 3.1.3). When Tissaphernes demanded their surrender, they responded with another appeal to Sparta. There had not been a clean break between the two, and the ties cultivated during the Ionian War prompted a series of expeditions to Asia Minor in the 390s that only ended when the Corinthian War demanded Spartan attention closer to home.67

Endnotes

- John Hyland, Persian Interventions: The Achaemenid Empire, Athens, and Sparta, 450–386 BCE (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018), 38–46; cf. Pierre Debord, L’Asie Mineure au IVesiècle (412–323 a.C.) (Pessac: Ausonius Éditions, 1999), 214.

- E.g., Donald. Kagan, The Fall of the Athenian Empire (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1987), 10–11; David M. Lewis, Sparta and Persia (Leiden: Brill, 1977), 114–16; Jacqueline de Romilly, “Thucydides and the Cities of the Athenian Empire,” BICS 13 (1966): 1–12. Some scholars have modified Thucydides’ declaration. Simon Hornblower, A Commentary on Thucydides, vol. 3 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 754, refers to the opposition to Athens in Ionia as an “ephemeral mood,” while H. D. Westlake, “Ionians in the Ionian War,” CQ2 29, no. 1 (1979): 9–10, maintains that the Ionians were eager to recover their liberty, notes variations in regional attitudes; see below, “Contempt for Athenian Hegemony.”

- Debord, L’Asie Mineure, 203, regards the period 413–404 as a hinge that allows for the understanding of the fourth century. There is slippage in the naming conventions for the individual conflicts that made up the Peloponnesian War. The conventional term for the final years had become the Decelean War already in antiquity, probably reflecting the attitudes of Athenian writers, as Westlake, “Ionians in the Ionian War,” n. 1, suggests, but Thucydides refers to the war in Ionia as τοῦ Ἰωνικοῦ πολέμου (8.11.3). Since my focus is on the Ionian theater, I will use “Ionian War” to refer broadly to the final decade of the Peloponnesian War even though conventionally it only lasted from c.411 to 407/6.

- As Hornblower, A Commentary on Thucydides, 763–64, notes, Thucydides leaves out the article when identifying the ambassadors, indicating that they did not represent a unified group. Hyland, Persian Interventions, 50, suggests “careful prearrangement” to place the ambassadors there simultaneously, seeing these embassies as the culmination of Tissaphernes’ attempts to court Ionian elites. Cf. Marcel Piérart, “Chios entre Athènes et Sparte: La contribution des exiles de Chios à l’effort de guerre lacédémonien pendant la guerre du Péloponèse IG V 1, 1+SEG 39, 370,” BCH 119, no. 1 (1995): 253–82; T. J. Quinn, “Political Groups at Chios: 412 B.C.,” Historia 18, no. 1 (1969): 26–30.

- The simultaneous arrival of the two embassies was not a coincidence but reflects the changed stance of Persian central authority; see Hyland, Persian Interventions, 50–53.

- On the debate at Sparta, see Hornblower, A Commentary on Thucydides, 774–76.

- See Matthew Simonton, Classical Greek Oligarchy: A Political History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017), 193–94. On the divisions in the Chian polity in 412, cf. Jack Martin Balcer, Sparda by the Bitter Sea: Imperial Interaction in Western Anatolia (Providence, RI: Brown University Press, 1984), 525; Quinn, “Political Groups at Chios,” 22–30.

- For the use of informal networks for political ends, see Lynette G. Mitchell, Greeks Bearing Gifts: The Public Use of Private Relationships in the Greek World, 435–323 BCE (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 47–48. On Alcibiades’ family, see Chapter 3 n. 25.

- On Phrynicus, who subsequently became a supporter of the oligarchy of 411, see Nikos Karkavelias, “Phrynichus Stratonidou Deiradiotes and the Ionia Campaign in 412 BC: Thuc. 8.25–27,” AHB 27 (2013): 149–61.

- Curiously, Thucydides says that the setbacks at Miletus so enraged the Argives who made up about a quarter of the Athenian force that they picked up and went home (καὶ οἱ Ἀργεῖοι κατὰ τάχος καὶ πρὸς ὀργὴν τῆς ξυμφορᾶς ἀπέπλευσαν ἐκ τῆς Σάμου ἐπ ̓ οἴκου, 8.27.6).

- Westlake, “Ionians in the Ionian War,” 9–44; Lewis, Sparta and Persia, 114–16. Debord, L’Asie Mineure, 232 cautions that whatever Ionian enthusiasm existed in the early years rapidly waned. Balcer, Sparda, 425, limits enthusiasm to small factions in Ionia, while Akiko Nakamura-Moroo, “The Attitude of Greeks in Asia Minor to Athens and Persia: The Deceleian War,” in Forms of Control and Subordination in Antiquity, ed. Tōru Yuge and Masaoki Doi (Leiden: Brill, 1988), 568, rightly, I believe, rejects the premise of a Greek-Persian antithesis in Ionian thinking.

- Ronald P. Legon, “Samos in the Delian League,” Historia 21, no. 2 (1972): 156; Martin Ostwald, “Stasis and Autonomia in Samos: A Comment on an Ideological Fallacy,” SCI 12 (1993): 51–66; Graham Shipley, A History of Samos, 800–188 BC (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), 124–28. T. J. Quinn, Athens and Samos, Lesbos and Chios, 478–404 B.C. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1981), 21, argues that the coup was contained to the ruling oligarchy. Cf. Hornblower, A Commentary on Thucydides, 808–9.

- Ionia had a long history of endemic political conflict between those with land and those without it; see Alan M. Greaves, The Land of Ionia: Society and Economy in the Archaic Period (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), 91–94; and Chapter 2 in this volume. Thucydides labels the targets of this purge as οἱ γεόμοροι and τῶν δυνατωτάτων. The γεόμοροι are often identified as the landed aristocracy on the suspect evidence of Plutarch’s Graec. Quest. 57; see Marcello Lupi, “Il duplice massacro dei ‘geomoroi,’” in Da Elea a Samo: Filosofi e politici di fronte all’impero ateniese, ed. Luisa Breglia and Marcello Lupi (Naples: Arte Tipografica Editrice, 2005), 259–86. Cf. the discussion in A. Andrewes, A Historical Commentary on Thucydides, vol. 5 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981), 79, and Hornblower, A Commentary on Thucydides, 809. On regime breakdown and the development of this oligarchic faction, see Simonton, Oligarchy, 239–41.

- Andrewes, Historical Commentary on Thucydides, 44–49.

- Hyland, Persian Interventions, 83, is skeptical that “reintegration” of Miletus to Persia alone would have been enough to create this violent reaction, while the possibility of regime change might have. On Tissaphernes’ defensive strategy, see John W. I. Lee, “Tissaphernes and the Achaemenid Defense of Western Anatolia, 412–395 BC,” in Circum Mare: Themes in Ancient Warfare, ed. Jeremy Armstrong (Leiden: Brill, 2016), 264–69.

- Cnidus also expelled a Persian garrison (Thuc. 8.109), while the Greek sailors were angry with Tissaphernes over money; see Lee, “Tissaphernes,” 268; Hyland, Persian Interventions, 80–83.

- Lichas had connections throughout the Aegean (Plut. Cim. 10.5–6). On the proliferation of the name, see Simon Hornblower, “Λιχας καλος Σαμιος,” Chiron 32 (2002): 237–46. R. W. V. Catling, “Sparta’s Friends at Ephesos: The Onomastic Evidence,” in Onomatologos: Studies in Greek Personal Names Presented to Elaine Matthews, ed. R. W. V. Catling and Fabienne March-and (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 195–237, evaluates Laconian names in Ionia more broadly and notes that the name Lichas appears at Miletus.

- Hyland, Persian Interventions, 63. On the awkward phrasing of this treaty at Thuc. 8.37.5, see Hyland, Persian Interventions, n. 76. He is certainly correct that the τις τῶν πόλεων ὁπόσαι ξυνέθεντο βασιλεῖ is limited to poleis beyond Persian territory, meaning that most Ionians, once more claimed as Persian subjects, were not considered to have signed on to this treaty. Chios was in a different category.

- On this topos, see Joshua P. Nudell, “‘Who Cares about the Greeks Living in Asia?’: Ionia and Attic Orators in the Fourth Century,” CJ 114, no. 1 (2018): 163–90. On the treaties, see Hornblower, A Commentary on Thucydides, 800–802; Edmond Lévy, “Les trois traités entre Sparte et le Roi ,” BCH 107, no. 1 (1983): 221–41; Lewis, Sparta and Persia, 91; Pavel Nyvlt, “Sparta and Persia between the Second and the Third Treaty in 412/411 BCE: A Chronology,” Eirene 50, nos. 1–2 (2014): 39–60; Noel Robertson, “The Sequence of Events in the Aegean in 408 and 407 B.C.,” Historia 29, no. 3 (1980): 282–301; Christopher Tuplin, “The Treaty of Boiotios,” in Achaemenid History, vol. 2, ed. Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg and Amelie Kuhrt (Leiden: Brill, 1984), 138–42.

- Hyland, Persian Interventions, 71–74. He is also likely correct to largely redeem Tissaphernes of his alleged duplicity.

- On this eulogy, see Hornblower, A Commentary on Thucydides, 819–20.

- Mark Lawall, “Ceramics and Positivism Revisited: Greek Transport Amphoras and History,” in Trade, Traders and the Ancient City, ed. Helen Parkins and Christopher Smith (New York: Routledge, 1998), 86–89, 95, notes a decline in datable Chian finds at both Athens and Gordion in this period. The Athenians also liberated the rowers on Chian ships (Thuc. 8.15), and Thucydides notes that there was a larger number of enslaved people in Chios than in any polis other than Sparta (8.40.2).

- Astyochus is often blamed for early Spartan setbacks, but Caroline Faulkner, “Astyochus, Sparta’s Incompetent Navarch?,” Phoenix 53, nos. 3–4 (1999): 206–21, explains his actions and points out both the possible sources of Thucydides’ biases and the extreme difficulties facing any Spartan commander.

- Pedaritus is never referred to as ἁρμοστήν, which is a rare word that appears just once in Thucydides’ text (8.5.1, in reference to Euboea). Xenophon uses it once in the Anabasis (5.5.19) and eleven times in the Hellenica, including in reference to Lysander’s appointment to put down the revolt against the Thirty (2.4.28) and in reference to Thibron’s appointment in Ionia (3.1.4). Xenophon makes it clear that this was the standard term for Spartan governors, so we can reasonably assume that this was in fact Pedaritus’ position. On harmosts and decarchies, see below, “Enter Lysander.”

- E.g., Westlake, “Ionians in the Ionian War,” 26, 34.

- Xen. Hell. 4.5.13; Arist. Pol. 1321a14–21; Paul Cartledge, Agesilaos and the Crisis of Sparta (London: Duckworth, 2000), 45–46; Louis Rawlings, The Ancient Greeks at War (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007), 85–86; H. van Wees, ed., War and Violence in Ancient Greece (Swansea: Classical Press of Wales, 2000), 62–65.

- A question asked, but not answered, by John F. Lazenby, The Peloponnesian War: A Military Study (New York: Routledge, 2004), 208–9.

- See Lene Rubinstein, “Ionia,” in An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis, ed. Mogens Herman Hansen and Thomas Heine Nielsen (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 1094, and Chapter 6 in this volume.

- Lee, “Tissaphernes,” 270.

- The coins may be reflected by a series from Astyra in Aeolis, which also had a shrine for Artemis. Hyland, Persian Interventions, 102, shows that the series was designed to associate this small shrine with the famous sanctuary at Ephesus. This coin series was traditionally dated to Tissaphernes’ second stint in Ionia, 400–395; see Herbert Cahn, “Tissaphernes in Astyra,” AA 4 (1985): 592–93, but has been redated by Jarosław Bodzek, “On the Dating of the Bronze Issues of Tissaphernes,” Studies in Ancient Art and Civilization 16 (2012): 110–15.

- Lee, “Tissaphernes,” 273.

- On competition between satraps and the limited resources available to Pharnabazus and Tissaphernes compared with Cyrus’ wide remit, see Pierre Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire, trans. Peter T. Daniels (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2002), 593–96. Cyrus probably replaced Tissaphernes in this capacity; see Hyland, Persian Interventions, 107–8, who also notes the etymological link between karanos and strategos. Stephen Ruzicka, “Cyrus and Tissaphernes, 407–401 B.C.,” CJ 80, no. 3 (1985): 205–8, argues that Tissaphernes incorporated into Cyrus’ entourage to advise the inexperienced prince but received an appointment again in 404 as a reward for betraying him.

- Hyland, Persian Interventions, 149; John Hyland, “Thucydides’ Portrait of Tissaphernes Re-examined,” in Persian Responses, ed. Christopher Tuplin (Swansea: Classical Press of Wales, 2007), 1–25; Ruzicka, “Cyrus and Tissaphernes,” 204–11; H. D. Westlake, “Tissaphernes in Thucydides,” CQ2 35, no. 1 (1985): 43–54.

- Lewis, Sparta and Persia, 115, and Westlake, “Ionians in the Ionian War,” 40–41, deny any Persian presence, while Jack Martin Balcer, “The Greeks and the Persians: Processes of Acculturation,” Historia 32, no. 3 (1983): 257–67, follows Plutarch in seeing acculturation as a recent development in Ionia. Margaret C. Miller, “Clothes and Identity: The Case of Greeks in Ionia c.400 BC,” in Culture, Identity and Politics in the Ancient Mediterranean World, ed. Paul J. Burton (Canberra: Australasian Society for Classical Studies, 2013), 18–38, however, demonstrates that Persian and Anatolian features had become inextricable from local identity, where the Priest of Artemis held the Persian title Megabyxos (Xen. Anab. 5.3.4; Pliny N.H. 35.36, 40), cf. Chapter 9 and Appendix 2.

- Hyland, Persian Interventions, 118–21. His calculation excludes ancillary costs like mercenary salaries and pay for loggers and shipbuilders.

- On this honor, which is usually tied to Ephesus’ oligarchic regime, see Westlake, “Ionians in the Ionian War,” 41; Nakamura-Moroo, “Attitude of Greeks in Asia Minor,” 570; Kagan, Fall of the Athenian Empire, 302–3.

- Most of the Ionian contributions to the so-called Spartan War Fund (RO 151 = IG V 1, 1) likely belong in this context, as suggested by Piérart, “Chios entre Athènes et Sparte,” 253–82, but Rhodes and Osborne observe that there is no one date that works for all entries. They follow Angelos P. Matthaiou and G. A. Pikoulas, “Ἕδον Λακεδαιμονίοις ποττὸν πόλεμον,” Horos 7 (1988): 77–124, in suggesting that it was inscribed in phases starting in c.427 and concluding in the c.409. Cartledge, Agesilaos, 72–73, maintains a later date c.403, but the relatively small amount in the inscription (maybe just over thirteen talents total), as William T. Loomis, The Spartan War Fund: IG V 1, 1 and a New Fragment (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 1992), notes, suggests that it belongs in an early phase of Spartan fiscal management.

- What, exactly, Thucydides meant by “fortieth” (τεσσαρακοστός) is a matter of heated debate because this term does not correspond to any denomination of coin used in the Greek world. N. M. M. Hardwick, “The Coinage of Chios, 6th–4th century BC,” in Proceedings of the XI International Numismatic Congress, ed. Catherine Courtois, Harry Dewit, and Véronique Van Driessche (Louvain: Séminaire de Numismatique Marcel Hoc, 1993), 211–22, proposes that “for-tieth” was in effect an exchange rate where forty of a given Chian coin was equivalent to a single coin, in the case probably a Persian daric. Aneurin Ellis-Evans, “Mytilene, Lampsakos, Chios and the Financing of the Spartan Fleet (406–404),” NC 176 (2016): 11–12, identifies this Chian coin as likely being a third-stater coin.

- According to Plutarch, Lysander had returned to Cyrus the money he had not yet spent and told Callicratidas to ask for it himself (Plut. Lys. 6.1). Diodorus paints a portrait of Callicratidas as an upright young Spartan, saying that he punished anyone who tried to bribe him (13.76.2), and both Diodorus and Xenophon describe him as an energetic commander whose fleet aggressively pursued the war in Ionia.

- Like the “fortieth” (see n. 38), “pentedrachmia” is a term without correspondence to a denomination of Greek coin. Ellis-Evans, “Mytilene, Lampsakos, Chios,” 12–14, reasonably suggests the term indicates the amount paid rather than the denominations distributed.

- The lack of money to pay the soldiers is often attributed to a personal conflict between Lysander’s replacement Callicratidas and Cyrus (Xen. Hell. 1.6.6–7; Plut. Lys. 6.5–6), but Hyland, Persian Interventions, 112, argues that the tension arose because Cyrus’ readily available money was depleted.

- On the estimate of fifty talents, see Ellis-Evans, “Mytilene, Lampsakos, Chios,” 14, who astutely notes that Eteonicus’ forces had already been depleted by losses at Arginousae earlier in the year.

- Particularly Ellis-Evans, “Mytilene, Lampsakos, Chios,” 14–16.

- Earlier scholarship dated this coinage alliance to after the battle of Cnidus in 394, as John Buckler, Aegean Greece in the Fourth Century BC (Leiden: Brill, 2003), 133; George L. Cawkwell, “A Note on the Heracles Coinage Alliance of 394 B.C.,” NC 16 (1956): 69–75; George L. Cawkwell, “The ΣΥΝ Coins Again,” JHS 83 (1963): 152–54; Charles D. Hamilton, Sparta’s Bitter Victories: Politics and Diplomacy in the Corinthian War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1979), 230. More recent studies have convincingly redated the coins to Lysander’s second term in 405/4 following Stefan Karwiese, “Lysander as Herakliskos Krakonopnigon: (‘Heracles the Snake-Strangler’),” NC 140 (1980): 1–27; cf. Ellis-Evans, “Mytilene, Lampsakos, Chios,” 14–16. The Samian examples must date to the period shortly after his capture of the island.

- Lazenby, Peloponnesian War, 254–55; Hyland, Persian Interventions, 115.

- Erythrae is a restoration of a lacuna preferred by Hyland, Persian Interventions, 115 n. 107, following Lewis, Sparta and Persia, 115 n. 50 and contra Westlake, “Ionians in the Ionian War,” 27 n. 3, whose objection is that there would be no cause to refer to Erythrae in relation to Mount Mimas. Hyland aptly notes that the reference to Mimas is more likely specifying a place within the Erythraeid, perhaps indicating an otherwise unattested local conflict, than indicating contributions to some anonymous community. Cf. John Hyland, “The Aftermath of Aegospotamoi and the Decline of Spartan Naval Power,” AHB 33 (2019): 21–22, who notes that the allied contributions diminished after 404 in part because Lysander kept the captured Athenian fleet under Spartan control.

- The unusual features of this inscription, including its pictural relief and its destruction during the period of the Thirty Tyrants and subsequent reinscription by the restored democracy, have received a great deal of recent scholarly attention. Jas Elsner, “Visual Culture and Ancient History: Issues of Empiricism and Ideology in the Samos Stele at Athens,” CA 34, no. 1 (2015): 33–73, and Alastair Blanshard, “The Problem with Honouring Samos: An Athenian Documentary Relief and Its Interpretation,” in Art and Inscriptions in the Ancient World, ed. Zahra Newby and Ruth Leader-Newby (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 19–37, are the two more complete treatments of the stele, incorporating both the inscription and the images. For a summary of approaches, see Elsner, 46–48.

- Shipley, Samos, 131, highlights that Xenophon calls the new regime “its one-time citizens,” probably indicating the exiles at Anaia.

- Shipley, Samos, 133–34, suggests that the epigram may have been added later.

- Lysander likely intended Choerilus to compose a contemporary epic along the lines of his Persica that debuted in Athens to such acclaim that the Assembly allegedly awarded him a gold stater per line and decreed that it should be recited alongside the works of Homer (Suda s.v. Χοιρίλος). George Huxley, “Choirilos of Samos,” GRBS 10, no. 1 (1969): 13, correctly notes that there is no evidence that Choerilus ever began this poem. On Choerilus’ treatment of the contemporary in the form of epic, see Kelly A. MacFarlane, “Choerilus of Samos’ Lament (SH 317) and the Revitalization of Epic,” AJPh 130, no. 2 (2009): 219–34. The Lysandreia became one of the preeminent literary festivals in Ionia during this period and is attested by inscriptions recording victories such as IG XII 6.1 334. The Lysandreia attracted poets such as Antimachus of Colophon, who wrote an acclaimed Thebaid, about the Seven Against Thebes, and whose poetry was equated with Homer and Hesiod and sought after by Plato because it was unavailable in Athens. He evidently lost in his appearance at the Lysandreia, though perhaps not strictly because Lysander approved more of Niceratus of Heracleia’s poem, as Plutarch suggests (Lys 18.4).

- Michael A. Flower, “Agesilaus of Sparta and the Origins of the Ruler Cult,” CQ2 38, no. 1 (1988): 132–33; Frances Pownall, “Duris of Samos (76),” BNJ F 71 commentary. Simonton, Oligarchy, 208–10, incisively demonstrates how these rituals served to reinforce the new regime.

- E.g., E. Cavaignac, “Les dékarchies de Lysandre,” REH 90 (1924): 292–93; C.D. Hamilton, “Spartan Politics and Policy, 405–401 B.C.,” AJPh 91, no. 3 (1970): 297–98; Kagan, Fall of the Athenian Empire, 397; H. W. Parke, “The Development of the Second Spartan Empire (405–371 B.C.),” JHS 50, no. 1 (1930): 51–53, though Parke acknowledges, “A precise answer to the question, where . . . Lysander left harmosts and decarchies, and where harmosts without decarchies, or merely ungarrisoned oligarchies, is precluded by our lack of evidence.” The source problems surrounding the decarchies has led to a notably slim modern bibliography. The two clearest discus-sions are Hamilton, Sparta’s Bitter Victories, 37; David M. Lewis, “Sparta as Victor,” in Cambridge Ancient History 2, vol. 6, ed. David M. Lewis, John Boardman, Simon Hornblower, and Martin Ostwald (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 29–30.

- Xenophon says that Lysander went to Ionia in the 390s so that he could “restore with the help of Agesilaus the decarchies he had established in the cities and dissolved by the ephors” (ὅπως τὰς δεκαρχίας τὰς κατασταθείσας ὑπ ̓ἐκείνου ἐν ταῖς πόλεσιν ἐκπεπτωκυίας δὲ διὰ τοὺς ἐφόρους . . . πάλιν καταστήσειε μετ ̓Ἀγησιλάου, 3.4.2), but makes no mention of which cities had had decarchies. In reporting Lysander’s motivations for the campaign, Xenophon likely makes general a practice that had been more limited.

- Diodorus’ text says that the Milesian exiles took refuge with Pharnabazus, but A. Andrewes, “Two Notes on Lysander,” Phoenix 25, no. 3 (1971): n. 15 notes confusion and conflation of the Persian satraps, whom Diodorus at times calls “Pharnabazos” interchangeably, and thus reasonably amends the satrap in this passage to Tissaphernes. Lydia is also significantly closer to Miletus than Hellespontine Phrygia, and we hear of Milesian “friends” of Tissaphernes who formed part of his retinue until his death in 395 (Polyaenus 8.16).

- The toponym “Blauda” is unknown, but Strabo locates a “Blaudos” in Lydia (12.5.2), making an identification likely; see Andrewes, “Two Notes on Lysander,” n. 15.

- Vanessa B. Gorman, Miletos, the Ornament of Ionia (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2001), 240–41. Diodorus mentions Lysander in the aftermath of the coup (13.104.7), but not in connection to it.

- As a source of evidence for specific trends in Milesian political history this inscription should be taken with extreme skepticism, but the second column (II. l.2) may begin with the repudiation of Athens, and the names could be read as a particular faction becoming ascendent since entries for Hegemon, son of Eodemos (II. 1.4, in perhaps 410/9), and Eodemos, son of Hegemon (II. l.12, 402/1), two names that together appear only once elsewhere on the list (Eodemos, I. l. 90), may indicate a father-son pair. Recently, however, Eric W. Driscoll, “The Milesian Eponym List and the Revolt of 412 B.C.,” The Journal of Epigraphic Studies 2 (2019): 11–32, has argued that a new fragment of the list ought to be interpreted as indicating that the stele first went up in 412 as a way of galvanizing the divided community.” There is also a double entry, likely in 403/2 at II. l. 11, but should that quirk hold any significance it would be to the conflict between Tissaphernes and Cyrus. On the inscription, see Chapter 2 and Chapter 7.

- Hamilton, “Spartan Politics and Policy,” 294–314. Flower, “Agesilaus of Sparta,” 123–34, suggests that the development of the ruler cults lay behind the falling out between Agesilaus and Lysander, while Graham Wylie, “Lysander and the Devil,” AC 66 (1997): 75–88, implies that Lysander was corrupt and rotted to the core. On the end of the decarchies, see Andrewes, “Two Notes on Lysander,” 206–14.

- Contra Andrewes, “Two Notes on Lysander,” 216, who argues that Cyrus allowed Lysander an entirely free hand throughout Ionia until it was no longer politically expedient.

- Andrewes, “Two Notes on Lysander,” 216.

- Hamilton, “Two Notes on Lysander,” 294–314; Lewis, “Sparta as Victor,” 40–41; Lewis, Sparta and Persia, 137. For a revised interpretation of the power dynamics, see Hyland, Persian Interventions, 99–12. Jeffrey Rop, Greek Military Service in the Ancient Near East, 401–330 BCE (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), argues that the subsequent service of Greeks in Persian forces indicates the influence of Persian political patronage in the Aegean during the fourth century.

- See Debord, L’Asie Mineure, 120–24, 166, 224; Jack Martin Balcer, “The Ancient Persian Satrapies and Satraps in Western Anatolia,” AMI 26 (1993): 81–90; Ruzicka, “Cyrus and Tissaphernes,” 204; Lewis, Sparta and Persia, 129–32.

- Ruzicka, “Cyrus and Tissaphernes,” 207–8; Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones and James Robson, Ctesias’ History of Persia: Tales of the Orient (New York: Routledge, 2009), 197; Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander, 615–16.

- Ruzicka, “Cyrus and Tissaphernes,” 208–9. Cf. Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander, 616–17; Debord, L’Asie Mineure, 124–26.

- Hyland, Persian Interventions, 125–26.

- Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander, 616–20; Hamilton, Sparta’s Bitter Victories, 103–4; Ruzicka, “Cyrus and Tissaphernes,” 210–11; M. Waters, Ancient Persia: A Concise History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 177–81

- Contra Hamilton, Sparta’s Bitter Victories, 107–8, who argues that the ascendancy of a conservative faction in Sparta at the end of the Peloponnesian War meant a complete withdrawal of ties.

Chapter 4 (67-89) from Accustomed to Obedience?: Classical Ionia and the Aegean World, 480-294 BCE, by Joshua P. Nudell (University of Michigan Press, 03.06.2023), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.