From gruesome, public executions to Georgian Britain’s adoration of the ‘heroic’ highwayman, the author investigates attitudes to crime and punishment in Georgian Britain.

By Dr. Matthew White

Visiting Research Fellow

University of Hertfordshire

Introduction

Throughout this period many people viewed criminals and law breaking as heroic and courageous, and the activities of robbers and villains were often widely celebrated in popular culture. Stories of daring criminality were widely reported in a host of printed pamphlets, books and newspapers, and generated high levels of public interest across the country.

Highwaymen in particular were held in high esteem by many people. Tales of highway robbery often became the stuff of folklore and legend, and several highwaymen became popular celebrities in their own lifetime. When street robber Jack Sheppard was hanged in 1724 after making four escapes from prison, 200,000 people attended his execution. When the celebrated 18th-century highwayman John Rann was let off for a theft in 1774, he was mobbed by a crowd of adoring admirers as he left court in London. The newspaper articles below paint vivid pictures of Rann in court.

For others, however, rising crime was the cause for much concern. Theft rates in particular remained alarmingly high and by the second half of the century many people were beginning to question the effectiveness of the methods used to investigate and arrest wrongdoers.

Law Enforcement

18th-century law enforcement was very different from modern-day policing. The prosecution of criminals remained largely in the hands of victims themselves, who were left to organise their own criminal investigations. Every parish was obliged to have one or two constables, who were selected every year from local communities, and were unpaid volunteers. These constables were required to perform policing duties only in their spare time, and many simply paid for substitutes to stand in for them.

In London, a system of paid watchmen also operated across different parishes. Known as ‘charlies’, they performed various duties on top of the detection and arrest of suspected criminals, including escorting home drunkards and ‘crying’ the time through the streets of their neighbourhood during the night. London’s watchmen were widely criticized for being old, decrepit and ineffective, though many probably served a useful function to many local communities.

From the 1750s, however, this patchwork system of local policing was strengthened by a more professional force of officers. In 1751 London magistrate Henry Fielding founded the Bow Street Runners, who for the first time provided a permanent body of armed men to carry out investigations and arrests.

The Courts

The vast majority of criminal cases during the 1700s were brought before local magistrates, who dealt with crimes without the benefit of a jury. Magistrates were themselves unpaid officials who were drawn from the ranks of the wealthy, and were expected to defend the English law as amateurs. As a result, many magistrates were easily corrupted. In London, Horace Walpole believed that ‘the greatest criminals of this town are the officers of justice’. Though magistrates were extremely powerful men, many found their duties extremely burdensome and often dealt with their heavy caseloads with great reluctance.

For more serious crimes such as rape or murder, cases were referred to Crown courts, who sat at quarterly assizes in large towns or at the Old Bailey in London. For the ordinary citizen, trials at these higher courts were hugely intimidating experiences. Courtrooms were sprinkled with herbs and scented flowers in order to prevent the spread of disease and to mask the smell of unwashed prisoners, while much of the courts’ daily business was conducted in Latin. Most felony cases did not involve defence barristers until the end of the century, and witnesses were usually examined directly by the judge and even by members of the jury. The vast majority of cases lasted for only a matter of minutes, and it was not uncommon for dozens of cases to be heard in a single day.

Punishments

The 18th-century criminal justice system relied heavily on the existence of the ‘bloody code’. This was a list of the many crimes that were punishable by death – by 1800 this included well over 200 separate capital offences. Guilty verdicts in cases of murder, rape and treason – even lesser offences such as poaching, burglary and criminal damage – could all possibly end in a trip to the gallows. Though many people charged with capital crimes were either let off or received a lesser sentence, the hangman’s noose nevertheless loomed large.

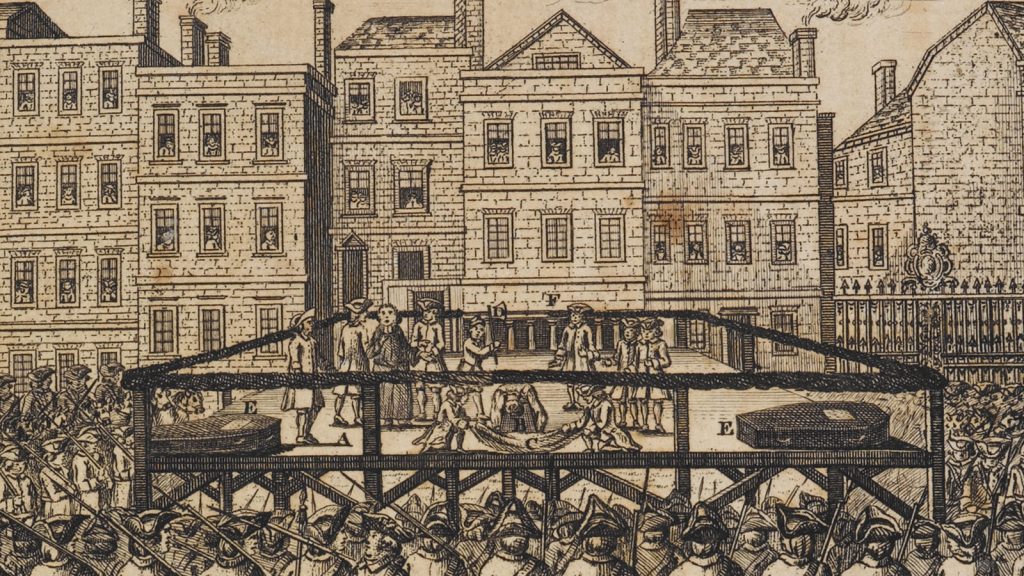

Most punishments during the 18th-century were held in public. Executions were elaborate and shocking affairs, designed to act as a deterrent to those who watched. Until 1783 London executions took place at Tyburn eight times a year, where as many as 20 felons were sometimes hanged at the same time. Prisoners were transported to the gallows along a three-mile route by cart, often followed by a huge, jeering crowd numbering several thousand people. Prisoners were executed in front of these noisy, riotous audiences and many hangings resembled more of a fair than a solemn legal ceremony. Other hangings, by contrast, were sombre affairs, accompanied by deep mourning and widespread commiseration for the condemned. White doves were sometimes released by the spectators as a symbol of their sorrow, and executions were accompanied by a hushed silence as the frightening moment of death arrived.

A range of other punishments were, however, also frequently imposed. Many felons were transported to the American colonies (and later in the century, to those in Australia), where they served out their sentences in hard labour. Other criminals convicted of lesser crimes were fined, branded on the hand by a hot iron, or shamed in front of the general public: by being whipped ‘at the cart’s tail’, for example, or being set in the pillory and pelted with rotten eggs and vegetables. Long-term prison sentences in ‘Houses of Correction’ were also more widely imposed towards the century’s end.

Originally published by the British Library, 10.14.2009, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.