Its final form was shaped by a wide array of ideological, political, and regional pressures.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

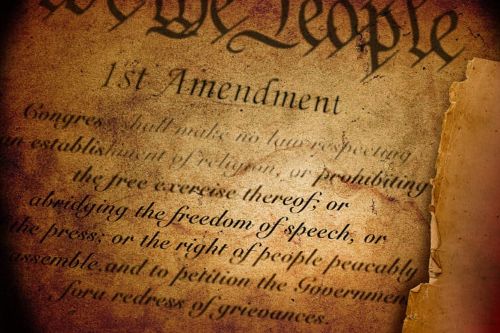

The First Amendment of the United States Constitution stands today as a cornerstone of American democracy, enshrining the freedoms of religion, speech, press, assembly, and petition. Yet the path to its inclusion in the Bill of Rights was neither straightforward nor uncontested. The debates among the Founding Fathers surrounding the drafting and adoption of the First Amendment reflect deep philosophical divisions over the nature of liberty, the scope of governmental power, and the role of individual rights in a republican society. This essay examines the historical context, ideological conflicts, and political maneuvering that shaped the First Amendment, emphasizing the diversity of opinion that characterized the founding generation.

Missing Safeguards and Original Oversight: Constitutional Context and the Absence of a Bill of Rights

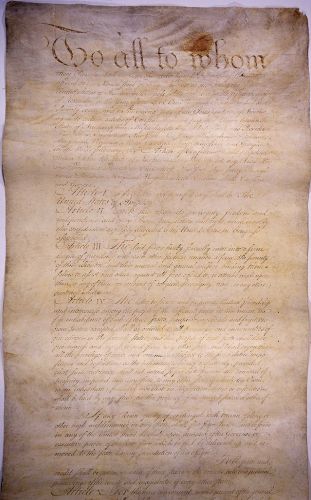

The Constitution of 1787 emerged from the Philadelphia Convention with a detailed framework for a new federal government but lacked any explicit declaration of individual rights. This omission was not accidental but reflected a deliberate decision by the majority of the Framers, who believed that a Bill of Rights was unnecessary and potentially dangerous. They argued that the Constitution, as a charter of enumerated powers, inherently limited the federal government. Since Congress had only those powers expressly granted to it, it was thought incapable of infringing upon individual liberties unless expressly permitted to do so. Alexander Hamilton articulated this view in Federalist No. 84, asserting “why declare that things shall not be done which there is no power to do?” and warning that enumerating rights could provide a pretext to infer powers not granted.1 This line of reasoning carried significant weight among the Federalists during the debates over ratification.

Nonetheless, the lack of a Bill of Rights became one of the Anti-Federalists’ most powerful and enduring criticisms of the Constitution. The Anti-Federalists—figures such as George Mason, Patrick Henry, and Elbridge Gerry—feared that the absence of explicit protections for freedoms like speech, religion, and the press would leave citizens vulnerable to federal encroachment. George Mason, a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, famously refused to sign the final document in part because it lacked a declaration of rights similar to that in his own Virginia Declaration of Rights of 1776.2 Anti-Federalist publications circulated widely, warning of tyranny and the erosion of liberties under the proposed federal structure. These objections, while insufficient to halt ratification outright, fostered a popular demand for amendments to secure personal freedoms and limit governmental overreach.

The Federalists, in response, found themselves politically compelled to promise a Bill of Rights in order to secure the Constitution’s ratification. Although many Federalists remained skeptical, leaders such as James Madison recognized the strategic necessity of compromise. Madison, initially dismissive of a Bill of Rights, came to appreciate its potential for unifying the new republic and defusing Anti-Federalist opposition. In a letter to Thomas Jefferson in 1788, he acknowledged the need for amendments that would “give to the Government its due popularity and stability.”3 Once elected to the First Congress, Madison made good on his promise, introducing a slate of amendments that would become the Bill of Rights. His proposals were not radical assertions of new principles but rather codifications of rights long held to be central to Anglo-American political tradition.

The First Amendment’s inclusion among these amendments reflected Madison’s—and others’—deep concern for the fundamental freedoms associated with self-government and individual dignity. However, even Madison’s proposed amendments were tempered by Federalist caution. His original list of amendments included detailed protections against both federal and state encroachments, but these were revised during congressional debates to apply only to the federal government.4 This limitation meant that state governments, many of which continued to have established churches and restrictions on speech or assembly, remained unaffected by the federal Bill of Rights. It was only through later judicial interpretation, particularly under the doctrine of incorporation in the twentieth century, that the First Amendment’s protections came to bind state governments as well.

The absence of a Bill of Rights in the original Constitution was not a mere oversight, but a reflection of the Framers’ priorities and their divergent understandings of republican liberty. For many Federalists, the Constitution’s structural safeguards—separation of powers, checks and balances, and federalism—were sufficient to prevent tyranny. For the Anti-Federalists and a growing portion of the American public, however, these mechanisms needed to be supplemented with explicit guarantees of rights. The First Amendment, when it finally took shape in 1791, was the product of this fraught and complex debate—a debate that revealed both the strengths and the limitations of the new constitutional order and that continues to inform discussions of liberty in the United States today.

From Skeptic to Champion: James Madison’s Reluctant Journey to the First Amendment

James Madison’s eventual advocacy for a Bill of Rights—and the First Amendment in particular—was not the product of original conviction but of political expediency and philosophical evolution. At the time of the Constitutional Convention and the subsequent ratification debates, Madison aligned with the Federalist perspective that a Bill of Rights was unnecessary for a government of limited, enumerated powers. He shared Alexander Hamilton’s concern that enumerating certain rights might imply that any right not listed was unprotected and thereby subject to infringement by implication.5 Moreover, Madison believed that the structural protections embedded in the Constitution—separation of powers, federalism, and regular elections—would provide a more effective safeguard against tyranny than a set of declaratory statements.6 In this framework, rights were preserved not by parchment barriers but by institutional checks and balances. His early writings and speeches reflected a consistent skepticism of the need for codified rights.

Yet Madison’s position began to shift during the intense ratification debates of 1787–1788, particularly in his home state of Virginia, where Anti-Federalists such as George Mason and Patrick Henry mounted vigorous opposition to the Constitution. They pointed to the absence of a Bill of Rights as evidence that the new government would be unaccountable and prone to overreach. Madison, keenly aware of the fragility of the ratification effort, recognized that outright opposition from Virginia could threaten the entire constitutional project. In the Virginia ratifying convention of 1788, Madison reluctantly conceded that amendments might be necessary to ensure broader acceptance of the Constitution, even if he continued to doubt their utility from a theoretical standpoint.7 He resisted calls to delay ratification until a Bill of Rights could be added, instead proposing that the Constitution be ratified with a recommendation that amendments be considered afterward—a compromise that proved decisive.

Madison’s deeper conversion occurred not only in response to political pressure but also through correspondence and philosophical dialogue, especially with Thomas Jefferson. In a 1788 letter from Paris, Jefferson urged Madison to embrace a Bill of Rights as a means of reinforcing popular support and limiting the potential for abuse.8 Jefferson argued that even the best-constructed governments needed clear boundaries to prevent the natural encroachments of power. Madison, influenced by this and other considerations, began to see a Bill of Rights not merely as a concession but as a potential instrument for reinforcing the Constitution’s legitimacy and unifying a divided public. By early 1789, having secured a seat in the First Congress, Madison had embraced the task of drafting a set of amendments that would address Anti-Federalist concerns without undermining the federal structure he had helped construct.

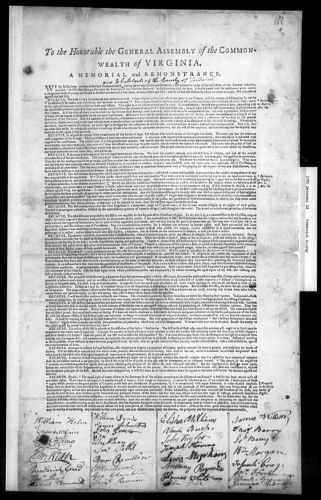

Madison approached the drafting process with great care and deliberation. In June 1789, he introduced a series of amendments that drew upon the various declarations of rights proposed by the state ratifying conventions. His strategy was both conciliatory and strategic: by placing the amendments in the Constitution’s text (rather than as addenda), and limiting their scope to the federal government, Madison sought to preserve the integrity of the original document while fulfilling the promises made during ratification.9 Among his proposed amendments were protections for religious liberty, freedom of speech and the press, and the rights of assembly and petition—principles that would coalesce into the First Amendment. Madison’s original language for religious freedom closely echoed his earlier Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments (1785), demonstrating continuity in his commitment to conscience, even as his views on codification had evolved.

Despite Madison’s commitment, the road to adoption was neither swift nor smooth. His proposed amendments were referred to a select committee and then revised extensively in the House and Senate. Some of his more ambitious proposals—such as applying the amendments to the states—were removed, reflecting the persistent caution of many Federalists.10 Yet Madison’s perseverance paid off. By December 1791, ten of the twelve amendments approved by Congress had been ratified by the states and became known as the Bill of Rights. Madison had, in effect, transformed from a skeptic to the principal architect of the very protections he once questioned. His conversion was not abrupt but gradual, forged in the crucible of political necessity and intellectual engagement. The First Amendment, with its guarantee of freedoms essential to democratic life, became a lasting testament to his capacity for adaptation and statesmanship.

Sacred Boundaries: Religion, Liberty, and the Birth of the Establishment Clause

The Establishment Clause of the First Amendment—”Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion”—was born out of the unique and often contentious religious landscape of late eighteenth-century America. Unlike Europe, where a single national church was common, the American colonies had developed a diversity of religious establishments and dissenting communities. In New England, Congregationalism retained official support, while the South, particularly Virginia, had long maintained Anglican establishments. However, the Enlightenment ideals of religious liberty, combined with evangelical dissent and growing secularism, fostered an emerging consensus that state-sponsored religion was both unjust and politically divisive. This conviction gained powerful expression in the thought of figures like James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, who saw state interference in religion as a violation of natural rights.11 The Establishment Clause thus arose not from abstract theory alone but from practical experience with coercive religious institutions.

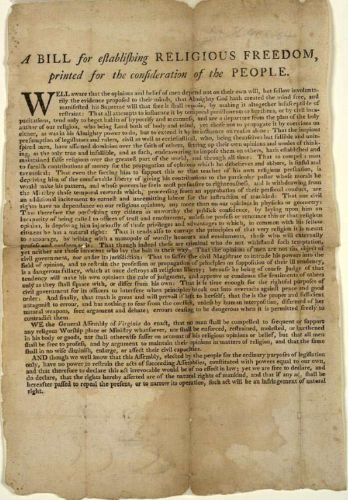

James Madison’s leadership in drafting the First Amendment was deeply informed by his earlier experiences opposing religious assessments in Virginia. In his Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments (1785), Madison had warned that compelling citizens to support religion financially violated their liberty of conscience and threatened both civil and ecclesiastical integrity.12 He rejected the argument that non-preferential support for religion was benign, arguing instead that true religious exercise must be voluntary and uncoerced. These views resonated with a broad cross-section of American Protestants, particularly Baptists and other dissenters, who had long resisted state-sanctioned churches. Madison’s 1789 draft of the religion clauses, introduced in the First Congress, reflected these concerns, proposing that “the civil rights of none shall be abridged on account of religious belief or worship.”13 Though the final language was more concise, its intent was clear: to prevent federal interference with religious belief, including the establishment of any national church or religious orthodoxy.

The congressional debates over the religion clauses illustrate the complexity of consensus among the Founders. While Madison and others favored broad protections against establishment, many representatives were wary of language that might disrupt the religious status quo in their states. As a result, Congress settled on wording that limited only the federal government: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.”14 This formulation, though somewhat ambiguous, reflected a political compromise. It barred the federal government from creating a national church or preferring one faith over another but did not initially prohibit states from maintaining their own religious establishments. Indeed, at the time of the First Amendment’s adoption in 1791, several states continued to support established churches, and it was not until the Fourteenth Amendment’s incorporation doctrine in the twentieth century that the Establishment Clause came to apply to state governments.

Despite its constrained initial scope, the Establishment Clause represented a revolutionary departure from European models of church-state relations. The Founders were not universally secular in the modern sense—many believed religion was essential to republican virtue—but they shared a conviction that government entanglement with religious institutions posed dangers to liberty and political stability. Jefferson’s Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (1786), which declared that “no man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship,” became a touchstone for those advocating disestablishment, even if Jefferson himself played no direct role in drafting the First Amendment.15 Madison frequently referenced this statute as emblematic of the American commitment to religious liberty. In their view, government neutrality in matters of faith not only protected minority sects but also preserved the sanctity of religion itself by removing it from the corrupting influence of politics.

The Establishment Clause was a product of both principle and pragmatism. Its adoption marked the culmination of colonial dissent against religious coercion and the maturation of Enlightenment ideals within American political thought. Although its application would evolve significantly over the centuries, the clause laid the constitutional foundation for a unique approach to religious liberty—one that sought to protect both the free exercise of faith and the secular integrity of the state. For the Founders, this dual protection was not a contradiction but a necessity: only by refraining from religious establishment could the federal government secure genuine liberty of conscience. The debates, compromises, and philosophical commitments that shaped the Establishment Clause reveal a generation of statesmen navigating the delicate balance between belief and governance in a new republic.

Voices of Liberty: Crafting Freedom of Speech and the Press

Freedom of speech and of the press, enshrined in the First Amendment, were fundamental principles for many of the American Founders, rooted in both Enlightenment thought and the colonial experience of censorship. In colonial America, printing presses were often subject to licensing laws and seditious libel prosecutions, especially under British rule. The 1735 trial of John Peter Zenger, in which a jury acquitted a printer accused of libel against the royal governor of New York, became a touchstone for advocates of press freedom. Although the case did not establish a legal precedent, it sparked a powerful cultural belief in the importance of an independent press. By the time of the Revolution, newspapers had become a critical instrument in shaping public opinion and galvanizing support for independence. These experiences ingrained in the American political consciousness the notion that a free press was essential not only for personal liberty but also for republican governance and the checking of state power.16

When the Constitutional Convention met in 1787, the absence of an explicit guarantee of free speech and press in the proposed Constitution became a central critique among Anti-Federalists. Critics feared that a powerful new federal government might suppress dissent and manipulate public discourse, as European monarchies had done. Federalists, including Alexander Hamilton, initially argued that such protections were unnecessary, since the Constitution granted no explicit power to regulate speech or the press. However, the ratification debates, particularly in key states like Virginia and Massachusetts, made it clear that many Americans desired explicit constitutional protections for expressive freedoms. Prominent Anti-Federalists warned that the lack of a bill of rights was a fatal flaw, and state ratifying conventions frequently proposed amendments to guarantee these freedoms. James Madison, once skeptical of the need for amendments, came to see that including such guarantees was vital to secure public confidence in the new government.17

When Madison introduced his proposed amendments in the First Congress in 1789, he included a succinct but sweeping protection: “The people shall not be deprived or abridged of their right to speak, to write, or to publish their sentiments.” The final wording, adopted in what became the First Amendment, read: “Congress shall make no law… abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.” This phrasing, though brief, carried profound implications. While the Framers did not define the precise boundaries of these freedoms, they understood them as encompassing robust protection for political expression and the dissemination of ideas. In this context, “the press” referred broadly to all forms of printed communication, not merely professional newspapers. By prohibiting federal interference with speech and press, the amendment aimed to preserve the right of citizens to critique their government, advocate policies, and inform one another without fear of reprisal.18

The congressional debates over these clauses were notably sparse, perhaps reflecting a widespread consensus about their necessity, or a belief that their meaning was self-evident. Madison and his allies viewed free expression as a bulwark against tyranny—a mechanism through which the public could hold officials accountable and resist encroachments on liberty. Drawing on the writings of theorists like John Locke and Cato’s Letters, they affirmed that free governments must protect the right to discuss political matters openly.19 Even so, some ambiguities persisted. The amendment restricted only Congress, not state legislatures, and made no mention of the kinds of speech that might be excluded from protection, such as obscenity or incitement. These ambiguities would lead to significant legal and political battles in subsequent decades, especially during moments of national crisis, such as the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798.20

The protections for speech and press in the First Amendment were adopted in response to both practical and ideological concerns. They reflected the Founders’ commitment to republican ideals, rooted in Enlightenment philosophy and colonial experience, and a recognition of the centrality of open discourse in self-government. While initially limited in scope—applying only to the federal government—the amendment set a powerful precedent for the role of free expression in American civic life. The decision to embed these freedoms in the Constitution was not merely a concession to Anti-Federalist pressure but a deliberate affirmation that liberty of expression was essential to the success of the republic. That principle, though challenged at times in American history, remains one of the most enduring legacies of the First Amendment.

Power in Protest: The Roots of Assembly and Petition

The rights to peaceably assemble and petition the government for a redress of grievances, enshrined at the end of the First Amendment, were deeply rooted in Anglo-American legal traditions and played a critical role in Revolutionary political culture. These rights were fundamental tools by which citizens expressed their collective will and challenged authority. The English Bill of Rights of 1689 had affirmed the right to petition the king, and colonial Americans expanded this notion into a broader conception of civic participation. Public meetings, town halls, and written petitions were not only avenues for airing grievances but also expressions of popular sovereignty. During the imperial crisis of the 1760s and 1770s, colonial resistance took the form of mass meetings, protest gatherings, and printed petitions to the Crown, creating a precedent for participatory politics that the Founders would later enshrine in constitutional form.21

The Revolution itself could not have succeeded without organized assemblies and petitions that coordinated resistance across the colonies. Groups like the Committees of Correspondence and the Sons of Liberty relied on meetings and declarations to mobilize opposition to British policies. The Continental Congress itself was a supra-colonial assembly that embodied the right to gather and deliberate. Petitions to Parliament and the king were key instruments in asserting colonial rights within the British imperial system before the turn to outright independence. These practices entrenched the idea that lawful assembly and petition were not acts of sedition but essential expressions of political agency. For many Americans, these rights were inseparable from the struggle for liberty and self-government.22

Like other First Amendment freedoms, the rights of assembly and petition were not explicitly protected in the original 1787 Constitution, prompting concern among Anti-Federalists. The Anti-Federalist critique focused not only on the potential for federal tyranny but also on the fear that a distant central government would suppress local civic engagement and dissent. Many ratifying conventions included calls for the protection of assembly and petition in their proposed amendments. These concerns reflected the lived experiences of citizens who had seen the power of collective action and who now demanded formal guarantees against governmental retaliation. For example, Pennsylvania and Virginia both recommended that “the people have a right to assemble together to consult for their common good.”23

James Madison responded to these calls by including the rights of assembly and petition in his draft amendments presented to the First Congress. The final language—“the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances”—was notable for its clarity and scope. It protected not only formal petitioning through written grievances but also the act of gathering itself. Madison and other proponents recognized that the freedom to congregate and express discontent was essential for a healthy republic. Though this right was framed as peaceful in nature, its importance lay in enabling public expression of dissent, a function that has repeatedly come under scrutiny during periods of civil unrest in American history.24

The inclusion of these rights in the First Amendment reflected a sophisticated understanding of the mechanics of democratic accountability. Whereas speech and press protected individual expression, the rights of assembly and petition preserved collective action. The Founders understood that public life required space for citizens to gather, discuss, and challenge policy through organized means. These rights were not ancillary to liberty but foundational to republicanism. Their adoption in the Bill of Rights represented both a recognition of the colonists’ experience with participatory resistance and a forward-looking commitment to protect future civic engagement. From the Whiskey Rebellion to the Civil Rights Movement, the legacy of the assembly and petition clauses has continued to shape the contours of American protest and the democratic dialogue.25

Promise to Practice: The Ratification and Early Life of the First Amendment

The ratification of the Bill of Rights, including the First Amendment, was not a foregone conclusion in 1789. While James Madison had successfully introduced the proposed amendments in the First Congress, many members of both houses were ambivalent or outright opposed. Some Federalists believed a bill of rights was unnecessary and potentially dangerous, fearing it would imply that unenumerated rights were unprotected. Nonetheless, Madison’s political skill and persistence ultimately led to the passage of twelve amendments by Congress, of which ten were ratified by the requisite three-fourths of the states by December 15, 1791. These ten amendments became what we now call the Bill of Rights. The First Amendment, coming first among these, symbolically anchored the new federal republic in a commitment to fundamental freedoms.26

The early interpretation of the First Amendment was shaped by both legal thought and political events. Initially, it was understood to apply only to the federal government, not to the states. This principle was underscored in Barron v. Baltimore (1833), where Chief Justice John Marshall explicitly stated that the Bill of Rights constrained only national power.27 In the decades immediately following ratification, there were few judicial decisions interpreting the First Amendment, in part because the federal judiciary was still relatively undeveloped, and in part because many of the principles it embodied were widely accepted in theory—if not always in practice. Public understanding of free speech, press, religion, assembly, and petition was largely shaped by political culture rather than courtroom jurisprudence.

Early challenges arose that tested the limits of First Amendment protections. The most famous of these was the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798 under President John Adams. These laws, particularly the Sedition Act, criminalized criticism of the federal government and were used to prosecute Republican editors and political opponents. Though defenders of the Act claimed it targeted only false or malicious statements, critics argued it violated the First Amendment’s core purpose. Madison and Jefferson responded with the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions, asserting that the federal government had overstepped its constitutional bounds and violated the rights of the people.28 These events revealed the tension between constitutional ideals and political expediency in the young republic.

It is important to note that the First Amendment’s original function was not judicially centered but politically protective. The Founders and their contemporaries expected that public opinion and the structure of republican government would act as the primary safeguards for liberty. The lack of immediate judicial enforcement mechanisms did not diminish the symbolic importance of the amendment; it was viewed as a moral and constitutional compass.29 Indeed, in the early republic, newspapers, pamphleteers, and protestors invoked the First Amendment frequently, even as courts were hesitant to enforce it robustly. The amendment helped define the parameters of political discourse and served as a rallying point in debates over federal power.

By the early 19th century, the First Amendment had become entrenched in American political identity, even though its legal enforcement was still embryonic. Its importance grew not through courtroom battles but through civic practice and public rhetoric. Gradually, Americans came to see these rights as essential to their national character and democratic institutions. Only in the 20th century would the First Amendment become the basis for a rich and expansive body of constitutional law through incorporation and judicial activism.30 But the foundational period laid the conceptual groundwork for these later developments. The ratification and early understanding of the First Amendment underscore its function as both a legal principle and a democratic ideal.

Conclusion

The First Amendment is often regarded as a clear and unequivocal commitment to fundamental freedoms. Yet its creation was the result of intense and complex debates among the Founders, reflecting competing visions of government, liberty, and order. While James Madison played a pivotal role in shepherding the amendment through Congress, its final form was shaped by a wide array of ideological, political, and regional pressures.

The Founders did not speak with one voice. Their disagreements over the First Amendment illuminate not only the richness of the American constitutional tradition but also the continuing need to interpret and apply these freedoms in an evolving democratic society. The First Amendment was a promise—born of compromise and contention—that liberty would endure. Its power lies not in its origin alone, but in the enduring debates it continues to inspire.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist No. 84, in The Federalist Papers, ed. Clinton Rossiter (New York: Signet Classics, 2003), 513.

- Gordon S. Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1969), 539.

- James Madison to Thomas Jefferson, October 17, 1788, in The Founders’ Constitution, Vol. 5, ed. Philip B. Kurland and Ralph Lerner (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987).

- Richard Labunski, James Madison and the Struggle for the Bill of Rights (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 174–175.

- Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist No. 84, 513.

- Jack N. Rakove, Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution (New York: Vintage, 1997), 291–292.

- Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 543-545.

- Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, July 31, 1788, in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 13, ed. Julian P. Boyd (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1956), 440–443.

- Labunski, James Madison and the Struggle for the Bill of Rights, 158-161.

- Kurland and Lerner, The Founders’ Constitution, Vol. 5, 18–22.

- Philip Hamburger, Separation of Church and State (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002), 105–107.

- James Madison, Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments (1785), in The Founders’ Constitution, Vol. 5, ed. Philip B. Kurland and Ralph Lerner (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 82–85.

- Labunski, James Madison and the Struggle for the Bill of Rights, 164.

- Kurland and Lerner, The Founders’ Constitution, Vol. 5, 92–94.

- Thomas Jefferson, Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (1786), in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 13, ed. Julian P. Boyd (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1956), 358–359.

- Leonard W. Levy, Emergence of a Free Press (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 3–9.

- Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787–1788 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 381–384.

- James Madison, “Amendments to the Constitution,” June 8, 1789, in The Founders’ Constitution, Vol. 5, ed. Philip B. Kurland and Ralph Lerner (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 151–153.

- Cato, Cato’s Letters, No. 15, 1721, in Ronald Hamowy, ed., Liberty and the Press: The Cato Letters (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1995), 45–47.

- Geoffrey R. Stone, Perilous Times: Free Speech in Wartime (New York: W. W. Norton, 2004), 18–22.

- Akhil Reed Amar, The Bill of Rights: Creation and Reconstruction (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 24–26.

- Pauline Maier, American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997), 38–41.

- Merrill Jensen, ed., Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution, Vol. 3 (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1978), 659–662.

- Madison, “Amendments to the Constitution,”, 151-152.

- Ronald J. Krotoszynski Jr., The Disappearing First Amendment (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 88–90.

- Rakove, Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution, 324-328.

- Barron v. Baltimore, 32 U.S. (7 Pet.) 243 (1833).

- James Madison, “Virginia Resolutions,” December 21, 1798, in The Papers of James Madison, vol. 17, ed. David B. Mattern (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1991), 303–308.

- Leonard W. Levy, Origins of the Bill of Rights (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 134–136.

- Amar, The Bill of Rights, 21-25.

Bibliography

- Amar, Akhil Reed. The Bill of Rights: Creation and Reconstruction. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

- Barron v. Baltimore, 32 U.S. (7 Pet.) 243 (1833).

- Cato. Cato’s Letters, No. 15, 1721. In Liberty and the Press: The Cato Letters. Edited by Ronald Hamowy. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1995.

- Hamilton, Alexander. The Federalist No. 84. In The Federalist Papers, edited by Clinton Rossiter. New York: Signet Classics, 2003.

- Jefferson, Thomas. The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 13. Edited by Julian P. Boyd. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1956.

- Jefferson, Thomas. Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (1786), in The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 13, ed. Julian P. Boyd. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1956

- Jensen, Merrill, ed. Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution. Vol. 3. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1978.

- Krotoszynski, Ronald J., Jr. The Disappearing First Amendment. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Kurland, Philip B., and Ralph Lerner, eds. The Founders’ Constitution, Vol. 5. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

- Labunski, Richard. James Madison and the Struggle for the Bill of Rights. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Levy, Leonard W. Emergence of a Free Press. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

- Levy, Leonard W. Origins of the Bill of Rights. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999.

- Madison, James. “Amendments to the Constitution,” June 8, 1789. In The Founders’ Constitution, Vol. 5.

- Madison, James. Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments. 1785.

- Madison, James. “Virginia Resolutions.” December 21, 1798. In The Papers of James Madison, Vol. 17. Edited by David B. Mattern. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1991.

- Maier, Pauline. American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

- Maier, Pauline. Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787–1788. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010.

- Rakove, Jack N. Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution. New York: Vintage, 1997.

- Stone, Geoffrey R. Perilous Times: Free Speech in Wartime. New York: W. W. Norton, 2004.

- Wood, Gordon S. The Creation of the American Republic, 1776–1787. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1969.

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.27.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.