The Cymmer Colliery disaster influenced the introduction of mine safety improvements including legislation.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

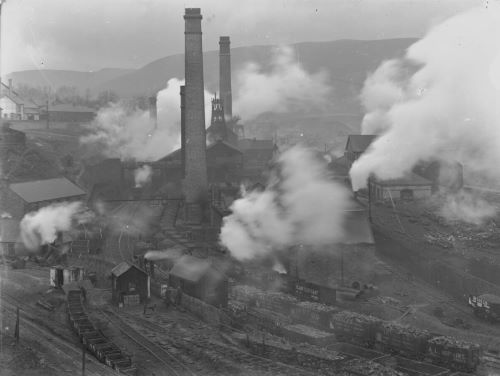

The Cymmer Colliery explosion occurred in the early morning of 15 July 1856 at the Old Pit mine of the Cymmer Colliery near Porth (lower Rhondda Valley), Wales, operated by George Insole & Son. The underground gas explosion resulted in a “sacrifice of human life to an extent unparalleled in the history of coal mining of this country”[1]: 141 in which 114 men and boys were killed. Thirty-five widows, ninety-two children, and other dependent relatives were left with no immediate means of support.

The immediate cause of the explosion was defective mine ventilation and the use of naked flames underground. Factors contributing to the explosion included the rapid development of the mine to meet increased demand for coal, poor mine safety practices allowed by management despite official warnings, and deteriorating working relationships between miners and management.

After the explosion, mine owner James Harvey Insole and his officials were accused of “neglecting the commonest precautions for the safety of the men and the safe working of the colliery”.[2]: 2 At the coroner’s inquest into the deaths, Insole deflected responsibility onto his mine manager Jabez Thomas and the jury brought a charge of manslaughter against Thomas and the four other mine officials. To the outrage of the local mining communities, the subsequent criminal proceedings resulted in the exoneration of the mine officials from any blame for the disaster.

The Cymmer Colliery disaster influenced the introduction of mine safety improvements including legislation for improved mine ventilation and the use of safety lamps, employment of children, and qualifications of mine officials. The tragedy highlighted the need for a workable compensation scheme for miners and their dependents to reduce their reliance on public charity after such disasters.

Background

George Insole and his son James Harvey Insole purchased the Cymmer Colliery in 1844. In 1847 they sank the No. 1 Pit which, after 1853, became known as the Cymmer Old Pit. James Insole took control of the business on his father’s death in 1851.[3][4]

Between 1852 and 1855, HM Inspector of Mines Herbert Francis Mackworth inspected the colliery twice and sent letters to Insole recommending safety improvements, in particular to the mine’s underground ventilation system and the use of safety lamps underground.[3][5]

Colliers (miners) relied on the colliery firemen’s daily reports of gas hazards before entering the mine. In 1854, mine manager Jabez Thomas summarily dismissed two experienced firemen and appointed two others from outside the colliery. The workmen complained to Insole they had no confidence in these replacements. The men’s refusal to work under the new firemen, and Insole’s insistence on exercising his “authority to dismiss or employ those whom I please, without consulting any body of men”,[3]: 133 led to a twenty-two week miners’ strike. Financial loss and threat of legal action eventually compelled the men to return to work under the new firemen.[a][3]

By the mid-1800s, the Rhondda variety of coal was in high demand as a coking coal.[6]: 48 The Crimean War created additional demand for coal, and in 1855 Insole intensified his mining operations at the Old Pit, doubling the number of colliers and increasing the mine area by over a third.[3] Welsh historian E. D. Lewis concluded that,

It was the success of [the Cymmer Old Pit mine] when developed with such inordinate speed and recklessness by [George Insole’s] son, James Harvey Insole, that led directly to the terrible mining disaster of 1856.[3]: 123

Explosion

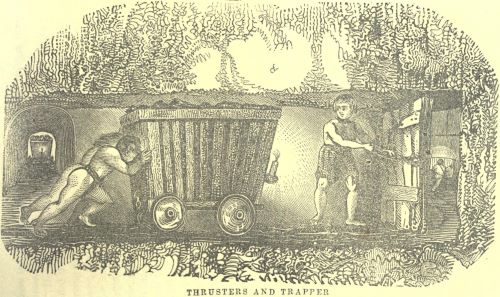

On Tuesday, 15 July 1856, 160 men and boys descended the Old Pit mine shaft to commence their 6:00 a.m. shift. As they made their way to their workplaces underground, there was an explosion of gas near the mine entrance which trapped the colliers already deeper in the mine. It was three hours before rescuers could reach the site. They found that many of the colliers had congregated in groups to die together as they ran out of air. By that evening,

112 bodies had been recovered, another was brought up the next day, and a severely burnt collier died the following day.[3][7][8] In his report to the Secretary of State for the year 1856, Mines Inspector Mackworth described the disaster as “the most lamentable and destructive explosion which had ever occurred in any colliery either in this country or abroad”.[5]: 118

Inquest

The coroner’s inquest into the deaths began on 16 July 1856 in Porth before the North Glamorgan coroner George Overton and a jury of eighteen. It was adjourned to allow the jurors to view the bodies and reconvened eleven days later in Pontypridd. Twenty-nine witnesses were called. The evidence indicated that the explosion resulted from defective mine ventilation and the use of naked flames underground, (Note: both the Davy lamp and Geordie lamp safety lamps had been invented in 1815, and widely used in mines at the time) despite warnings having been sent to the mine owner by Mackworth.[2][5] He told the inquest that “the explosion arose from the persons in charge of the pit neglecting the commonest precautions for the safety of the men and the safe working of the colliery”.[2]: 2

The inquest determined that, apart from the collier who died later of burns, all the deaths were the result of “suffocation, caused by the post-explosion effects of afterdamp or methane poisoning”.[3]: 138–139 Among the 114 victims, thirty-four were boys under the age of sixteen and another fifteen were under the age of twelve. Insole, the mine owner, walked free from the inquest after claiming he took “no part in management”[9] of the mine. The mine manager, Jabez Thomas, and the mine’s officials, Rowland Rowlands (overman), Morgan Rowlands (fireman), David Jones (fireman), and William Thomas (fireman), were charged with manslaughter for negligence causing the deaths of 114 men.[2][3][10]

Trial

At the Glamorgan Spring Assizes held in Swansea in March 1857, the judge, His Lordship Baron Watson, made his own position clear in his pre-trial address to the grand jury. Noting that the mine manager did not go underground, and that “no direct case of omission” had been brought against the other mine officials, he indicated that they could not be guilty of manslaughter.[1]: 142 Nevertheless, the grand jury returned a “true bill” (indictment) against Jabez Thomas, Rowland Rowlands, and Morgan Rowlands, who were then tried on the charge of “having feloniously and wilfully killed and slain one William Thomas,[b] on the 15th July, 1856″.[11] At the trial, it was reported that the judge made clear he sided with the defendants and thought the matter should not have come to court.[12]

At the conclusion of the trial, the jury complied with the judge’s directions to acquit the defendants.[1] To the deep distress and anger of the local mining communities, the final result of the legal proceedings was that the mine owner and his officials were exonerated from all blame.[3] However, E. D. Lewis’ analysis of the disaster concluded that:

Possibly the legal processes of the time were insufficient to punish those who were culpable, but of the moral responsibility of owner and officials, even when judged against the background of their own time and place, there can be no question.[3]: 153

Survivors

Among the small local communities no household was left untouched, almost all the working-age men and boys having perished. Thirty graves were opened at the Cymmer Independent Chapel graveyard and the bodies of forty-eight victims were interred on 17 July 1856 in the presence of huge crowds (estimated at 15,000 people). Smaller numbers of burials occurred in other local communities, with “11 at Tonyrefail, nine at Ffrwd Amos, eight at the Dinas Methodist Chapel, and the rest at Pontypridd, Treforest, Coed Cymmer, Llantrissant, Llanharry, Bedwas, Trelanos, Brynmenyn, Wauntrodau, Llanwonno”.[8][3][7] Thirty-five widows, ninety-two children, and other dependent relatives were left with no immediate means of support.[14] The court’s verdict meant the Fatal Accidents Act 1846, which required compensation to be paid only when a mine manager or proprietor was held to have been at fault, did not apply.[3]

However gross may have been the neglect which caused the husband’s death, all interests are arrayed against the survivors. The colliers, the jury, the means of legal redress, are subject to the influence … [of] the proprietor of the colliery. The cost of an administration, before an action can be commenced, and the difficulty of obtaining a solicitor who will undertake the odium and the risk, unite in forming an insuperable bar to the claim due to the widow and the fatherless, who, by the neglect or cupidity of others, have been plunged in one moment into the deepest affliction and most abject poverty.

Mines Inspector Mackworth’s report to the Secretary of State, 1855[15]: 118–119

The dependents of the victims of the disaster had to rely on public charity and “the final humiliation” of seeking poor relief.[3]: 160 [14] Insole contributed £500 (approximately equivalent to £49,700 in 2021) to the Cymer Widows’ and Orphans’ Fund, set up shortly after the disaster, and undertook to meet the cost of the thirty graves.[3][16] However, local coal owners also combined to deny work to those colliers who had given evidence against the mine officials at the inquest and trial.[3][5]Laments were published and, marking the first anniversary of the disaster, a song was published under the patronage of Mrs Insole of Ely Court (Insole’s wife) in aid of the relief fund.[17][18][19]

Legacy

Described by Mines Inspector Thomas Evans as a “sacrifice of human life to an extent unparalleled in the history of coal mining of this country”,[1]: 141 the Cymmer Colliery disaster of 1856 influenced future coal-mining practices, locally and nationally. After another gas explosion at the colliery in December 1856,[20] the single-shaft Cymmer Old Pit and New Pit mines were linked to create a safer and better ventilated two-shaft arrangement. Although mechanical mine ventilators had been used in the Lower Rhondda from 1851, they were installed at the Cymmer Colliery in the mid-1870s. Also by the mid-1870s, the colliery management realised it was safer and cheaper to provide colliers with safety lamps. The Cymmer Old Pit was worked by the Insole company until the mine closed in 1939.[3][6]: 149–160

More broadly, influenced by the number of children killed in the disaster, the Mines Regulation Act 1860 prohibited employment of boys under twelve years of age, unless they could read and write and were attending school for at least three hours a day on two days a week.[3] Two-shaft mines were made compulsory by 1865. Mackworth’s safety recommendations, sent to Insole in 1854 and including “that a qualified mining engineer and a sufficient number of competent subordinate officers and deputies should take complete charge of the machinery, ventilation, ways and works and watch over and provide for the safety of the workmen during the hours of labour”,[3]: 159 were passed in the Mines Act 1872. Following the Cymmer Colliery explosion, steps were taken to reduce the reliance on public charity in the case of fatal disasters by introducing comprehensive compensation schemes, but the first successful scheme did not emerge until 1881.[3][5][21][22]

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Originally published by Wikipedia, 01.24.2020, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.