Victims met with violence, intimidation, coercion, and deception.

By Dr. Christopher Paolella

Professor of History

Valencia College

Men, women, and children were all trafficked in Late Antiquity and throughout the early Middle Ages. Although the experiences of trafficking and enslavement were similar for all in that victims, regardless of their sex, met with violence, intimidation, coercion, and deception as a result of the dehumanization and commodification of abductees, the conditions of those experiences were nevertheless gendered. Sexualized violence against women and children remained a looming and perpetual threat in late antique and early medieval human trafficking activities that adult men generally did not face. While this fact should come as no surprise to anyone, the importance of this observation lies in continuity; the dangers of exploitation and violation for trafficked women and children remained a predictable constant that linked the slave trade of Late Antiquity and the early Middle Ages to the sex trafficking networks of the late Middle Ages and the early modern period.

As enslaved prepubescent children, both boys and girls commonly experienced sexual exploitation. In Antiquity, Jasper Griffin contends that relations with young boys, provided they were not freeborn, was quite common considering the Roman literary references, inscriptional evidence at Pompeii, and the regular accusations and scandals of the Late Republic. The Augustan state calendar recorded that boys employed in male prostitution (pueri lenoniorum) had their own official holiday on 25 April.1 In the Declamationes of the orator, Quintilian (c. 35–100), a foster father berates a man who abandoned his son, claiming that, ‘If it had been up to you […] beasts would have torn him [the abandoned son] apart, or birds would have carried him away, or, much worse, the pimp or the gladiator trainer would have gotten him.’2 Justin Martyr (c. 100–165) urged Christian parents to never abandon their children, ‘because we have observed that nearly all such [abandoned] children, boys as well as girls, will be used as prostitutes.’3 Lactantius (c. 250–325) decried the practice of child abandonment, claiming that exposed boys and girls ended up ‘either in slavery or the brothel.’4 Clement of Alexandria (c. 150–215) observed that enslaved boys were ‘beautified’ prior to display in the markets in order to attract potential buyers, and pondered, ‘How many fathers, forgetting the children they have abandoned, unknowingly have relations with a son who is a prostitute or a daughter who has become a harlot?’5

However, with the maturation process came sharply pronounced gendered differences in the experiences of enslavement and exploitation. As boys developed into men, they generally lost their sexual appeal to their male owners. As an example of cultural attitudes towards the sexual exploitation of adult male slaves, let us consider the Satyrica, a satire composed in the second half of the first century CE, and generally credited to Petronius (c. 27–66). The character Trimalchio, a wealthy former slave, now a slaveholder, imitates the opulent lifestyle of the Roman elite in part by owning a male slave for sexual exploitation. However, his ‘favorite’ (deliciae, literally ‘delights’) slave is too old (puer vetulus) and too ugly (lippus and deformus) for sexual exploitation according to contemporary social standards, and Trimalchio’s ignorance of these standards, along with his numerous other social faux pas, all serve to clearly and comically identify him as an outsider and an imposter.6

Late antique cultural standards of beauty dictated that sexual exploitation of male slaves generally tapered off as they matured, and so for adult men enslavement and sexual exploitation remained separate conditions. Under the threat of violence, adult male slaves supplied heavy, skilled, and occasionally sexual labor, and young male prostitutes (including slaves) worked in the sex industry, but there is little evidence suggesting a widespread, sustained cultural merger of adult male slavery and male prostitution. This is not to say that maturity made male slaves immune to sexualized violence. Slaves of either sex did not legally own their bodies, and therefore male slaves were always vulnerable to sexual exploitation and violence in the form of castration – the so-called ‘slave-dealer’s art’ (ars mangonis).7 The male slave was referred to as puer ‘boy,’ denoting not only legal helplessness similar to a child’s, but also a child’s physical helplessness, an inability to protect his physical integrity.8

For enslaved women, however, maturity brought the exact opposite experience. Jennifer Glancy observes that ‘social location is known in the body,’ and gendered physical relationships shaped the social relationships between the master and the slave that defined, and continue to define, slavery and human trafficking.9 As girls matured into women of childbearing age, society assumed their sexual exploitation throughout Late Antiquity and the early Middle Ages, and their exploitation was institutionalized in Roman jurisprudence.10 For women of childbearing age and for children, enslavement meant constant vulnerability and exposure to sexual assault and coerced prostitution to a degree that was generally unknown to their adult male counterparts.

The vulnerability of female slaves to sexual exploitation stemmed partly from the gendered division of labor among the enslaved. Because male slaves did highly visible work in fields and mines or conducted official transactions on behalf of the state or private transactions on behalf of their owners, their contributions to the state and household economies were recognized by social commentators of the times. Female slave work was dominated by what we might call the service industry. Slave women usually occupied domestic roles and served as wet nurses, governesses, and caretakers for sick or injured family members and small livestock. When they did engage in labor in public settings, they were used in textile production, food services and hospitality, or, like their male counterparts, as attendants in public baths. Social commentators in the Republic such as Cato (234–149 BCE), Varro (116–27 BCE), Columella (d. 70 CE), as well as jurists such as Q. Mucius Scaevola (d. 82 BCE), often dismissed female slaves as those who ‘did no work’ (opus non facere), because they did not view the duties of the female slaves as being particularly crucial to the finances of the household.11 The cultural diminishing of women’s labor and its contributions to the household and imperial economies, then, tacitly provided a socially acceptable reason for their sexual exploitation as their ‘contribution’ to the household. By deprecating the value of female slave labor, social commentators were then able to contend that the purposes of slave women were to demonstrate the wealth and opulence of her master, to provide him with a personal relationship that included sexual services, and to bear her owner a new generation of slaves.12

The slave woman’s ability to reproduce and create a new generation of slaves was a great advantage to her owner, particularly during the Principiate when the frontiers of the Roman Empire stabilized, and internal reproduction became an important source of new slaves. Usually, although not always, the legal status of the mother passed to her children. A practical implication of this legal framework was that a slaveholder could produce more slaves by impregnating his female slaves. He then had the option to formally recognize his progeny and thus liberate them from servitude, but there was no legal incentive and certainly little social pressure to do so. If a master allowed his slaves to start families, he also claimed ownership of any subsequent children. Thus for a variety of legal, economic, and libidinal reasons, slave purchasers sought out female slaves precisely because of their reproductive capacity.13

Society expected the exploitation of a female slave, and the woman was presumed to have had a sexual history regardless of whether or not she had actually been exploited.14 In a declamation of Seneca the Elder (54 BCE–39 CE), orators debated whether a respectable free virgin, having been kidnapped by raiders and sold into slavery in a brothel, could enter the priesthood after regaining her freedom even if she had somehow managed to preserve her chastity (by killing her would-be rapist). One of the orators, Publius Vinicus (f l. 2 CE), rejected the possibility with vivid imagery: ‘Do you regard yourself as chaste just because you are an unwilling whore? […] She stood naked on the shore to meet the buyers’ sneers; every part of her body was inspected and […] handled.’15 According to Vinicus, her objectification and her constant vulnerability to violation undermined her claims to have heroically defended her sexual integrity in a single encounter.

Rome was not the only society that assumed the sexual exploitation of female slaves. The Mishnah, the ‘Oral Law’ of Judaism, stipulates that converts to the faith, former captives, and freed slaves cannot be married as virgins.16 In the Early Christian Era, Ambrose of Milan (340–397) argued that the redemption of a Christian woman from ‘barbarian impurities, which are worse than death’ was a cause worthy of Church resources.17 Basil of Caesarea (330–379), in his exploration of the fickleness of fortune, observed that the whim of the master determined the potential for virtue of the slave: ‘She who is sold to a brothel-keeper is in sin by force, and she who immediately obtained a good master grows up with virginity.’ Moreover, he extended a pathway to virtue to enslaved Christian women by arguing that, ‘even a slave, if she has been violated by her own master, is guiltless.’18

The step from socially acceptable sexual exploitation of female slaves to the prostitution of female slaves was small indeed. As Susan Treggiari reasons,

Some girls are kept to work in the city household, others might perhaps be kept for their parents’ sake and as the delicia (the favorites or pets) of their owners, others might disappear to the country estates to work wool and produce children […] The prospects for girls who were sold would, if most rich families had a surplus of girls, be gloomy, the most likely purchasers be brothel-keepers or poor people who wanted a drudge.19

The concepts of female enslavement and prostitution were inseparable in Late Antiquity. In the second century CE, Artemidorus wrote in his treatise on the interpretation of dreams, ‘A courtesan imagined that she had entered the shrine of Artemis and she was freed and left behind her life as a courtesan. For one would not enter the shrine unless one had left behind one’s life as a courtesan,’ and as Glancy observes, she could not abandon prostitution as long as she was enslaved.20 In the fourth century, Jerome (c. 342–420) wrote sympathetically in a letter of a recently divorced woman whose former husband reportedly had ‘such heinous vices that even a prostitute or a common slave would not have put up with them.’21 John Chrysostom equated slaves and prostitutes as he set in stark relief the honor of free women against the dishonor of both of the former in his exhortations to the Christian men in his audience to refrain from illicit affairs with slave girls and prostitutes. In the fifth century, Basil of Seleucia (d. 458/460) relates an anecdote in which a woman, furious at her daughter’s rather active social life, exclaimed that the young lady was ‘spurning a marriage worthy of her patrimony and preferring the shameful life of a prostitute or slave girl!’22

Beyond metaphysical theory and social commentary, there is legal evidence for the social conflation of prostitutes and female slaves. The imperial tax codes on female prostitutes (prostitutae and meretricium quive lenocinium fecissent) and houses of prostitution, instituted by Caligula (r. 37–41) in 40 CE, included local variants that instructed tax collectors on the best methods of payment extraction from enslaved prostitutes and their owners.23 The Roman jurist Ulpian (d. 228), writing in the early third century, defined prostitution and pimps in relation to enslaved prostitutes. He writes,

He engages in prostitution [lenocinium] who has slaves [mancipia] for hire, though he who conducts this business with free persons is in the same situation. He is liable to punishment for lenocinium whether this is his principal occupation, or whether he carries on another trade (as, for instance, if he is an inn- or tavern-keeper and has slaves of this kind serving and taking the opportunity to ply their trade, or he is a bath-keeper having, as happens in certain provinces, slaves hired to look after clothing in the baths who are attentive in this way in their workplace). And Pomponius says that he who, while in servitude, had prostituted slaves on his own [peculiara] remains infamous after emancipation.24

Ulpian’s def inition of lenocinium casts a wide net that ensnares many of the roles and structures involved in the imperial sex industry. The leno, or pimp, is mainly a manager, and not necessarily the owner, of slaves who are prostituted not only in brothels but also in taverns, inns, and bathhouses. The legal status of the pimp is not necessarily a consideration; he may be free, freed, or a slave himself, but regardless of his legal position, his social position is middling, the manager of a business that wealthier people own or of which they are the principal investors, and to whom most of the profits flow. His legal opinion refers to slave prostitutes as mancipia, instead of servi or ancillae, which suggests that the ruling was crafted broadly enough to cover a wide range of future litigation that might include enslaved men, women, eunuchs, and children. Importantly, the enslaved status of those under the power of the pimp is emphasized, highlighting the social dynamics of domination and control involved in prostitution, pimping, and servitude. As Rebecca Flemming argues, the economic act of prostitution was one of others acting upon the prostitute (whether enslaved or free) who profited from her initial and then recurrent sale. She observes, ‘The modern verdict that, “Money is the reason for prostitution,” may be borne out by the ancient sources, but the money in question is presented not as an incentive for entering the profession, as it is now, but for establishing others in it.’25

Ulpian also crafted a legal definition for the ‘prostitute’ that flew in the face of the conventional wisdom of the day by eliminating the commercial nature of prostitution as a consideration. He did not, however, eliminate the association of femininity and prostitution.26 In his opinion,

We would say that a woman openly makes a living [by her body] not only where she makes herself available in a brothel, but also if (as is customary) she squanders her chastity in taverns, inns, and other places. Thus, we understand ‘openly’ as indiscriminately – that is without selection – not a woman who commits adultery or fornication, but one who maintains herself in the manner of a prostitute. Likewise, because she has intercourse with one or two, having taken money, it is not understood that she has openly made a living by her body. Also, Octavenus says, most correctly, that even a woman who makes herself openly available, without making a living, ought to be counted in this category […]. We call these women lenae who set out women for hire. We also understand as a lena she who leads this kind of life under another name. If a woman running an inn has slaves for hire in it (as many are accustomed to have prostituted women, on the pretext that they are servants of the inn), this must also be said to put her in the category of the lena.27

Ulpian thus defines a prostitute as a woman (and not a man) who makes absolute availability her way of life. In one sense, this is a rather broad definition. Remuneration is not a requirement, and a female pimp may be also labeled ‘prostitute.’ Yet paradoxically, his definition is also quite restrictive in that ‘open,’ ‘indiscriminately,’ and ‘without selection’ seem to be difficult standards to prove. Thus Ulpian excludes men from his definition of ‘prostitute,’ as well as women who occasionally engage in commercial sex during times of financial distress, or those women whose sexual behavior is essentially selective, even if considered scandalous by contemporary standards. The two rulings together strongly suggest that prostitution and female slavery had become fused in imperial jurisprudence by the early third century. The first definition considers slavery a prerequisite for the practices of pimping and prostitution in general, while the second defines prostitutes specifically as women and again underscores the central role of female slaves in prostitution.

Moving from cultural attitudes regarding prostitution and female servitude to concrete examples of such, a papyrus from Fayyum dated to about 265 CE details a legal battle involving the sale of a slave prostitute from a brothel in the environs of Arsinoë. A brothel-keeper named Pyrrhus, son of Podarius, and his unnamed partner managed several brothels but apparently ran into financial problems, and they fell behind on their rent payments. In order to pay down their debts, Pyrrhus sold off moveable property including a slave woman named Canthara who ‘had been with them formerly.’28 In perhaps the most concrete, violent, and visceral example of the fusion of the female slave and the prostitute during the Late Empire, a fourth-century lead and iron slave collar from Bulla Regia in North Africa bears the inscription, ‘I am a filthy prostitute. Hold me because I have fled from Bulla Regia.’29 The humiliation of the label adultera meretrix inscribed on the slave collar for public view is the voice of the woman’s owner, yet his words imply the humiliation, coercion, and violence from which she had fled.

Because gendered norms of honor and shame crossed legal strata in Late Antiquity, imperial authorities occasionally felt a sense of obligation to restrict the most degrading aspects of enslavement.30 Imperial decrees did not address the humiliation of the auction block upon which naked bodies were poked, prodded, and publicly examined (as Publius Vinicus so vividly described), but authorities nevertheless made attempts to regulate sex trafficking and to curtail the practice of prostituting the enslaved. Emperors and jurists ruled frequently to uphold the restrictive legal covenant known as ne serva prostituatur, which could be added to the sales terms of any female slave (serva) in order to prohibit her future prostitution by her new owners.31 According to the Scriptores Historiae Augustae, Hadrian (r. 117–138) prohibited the sale of slaves to pimps (lenones or lanistae) without just cause, and Septimius Severus (r. 193–211) impressed upon the Urban Praetor of Rome the obligation to protect slaves from being prostituted and to enforce the ne serva prostituatur covenants. This same emperor later ruled that a freedwoman could not be compelled to perform services for her patron and former master that would harm her reputation.32

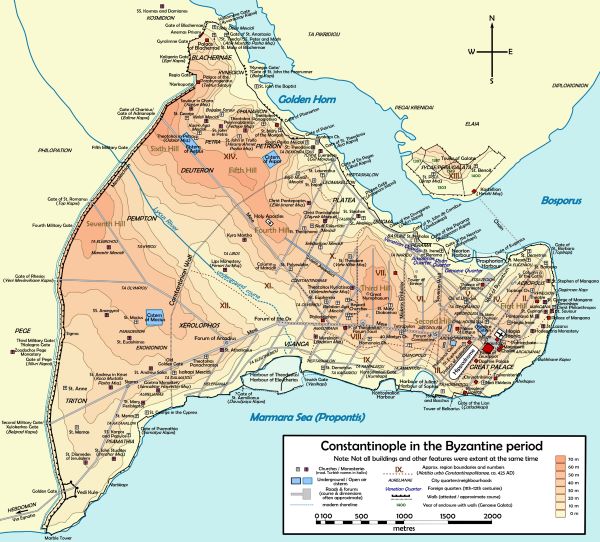

Legal caveats such as ne serva prostituatur, as well as social commentary and the numerous and repeated imperial limitations and prohibitions on the prostitution of female slaves, all vividly demonstrate the ubiquity of the practice. Yet gendered conditions of sexual exploitation in human trafficking that women experienced in Antiquity were not limited to the enslaved. There is also evidence for the sale of freeborn women into enslavement and prostitution by their families because, like slaves, dependents such as women and children were placed at a legal disadvantage that enabled their exploitation. Although qualifications were placed on these transactions, even the legislation of early Christian emperors did little to address the vulnerability of Roman dependents to enslavement and prostitution.33 The potential prof its a family might realize from the sale of a member do not appear extraordinary, although one may argue that, for the poverty-stricken, a small quick profit and one less mouth to feed were of no small consideration. Thomas McGinn contends that in the Late Empire, downward pressure on the market price of female slave prostitutes in Constantinople was exacerbated by the glut of freeborn trafficking victims also working in the sex industry. As McGinn poignantly observes, ‘Byzantine data suggests that it was not expensive for a pimp to set up shop.’34

The voluntary sales of kin by families did nothing to mitigate the dangers inherent in the sex industry that women and children then faced. A papyrus dated to the late fourth or early fifth century from Hermopolis, Egypt, details a court case involving an elderly woman named Theodora, who had sold her daughter into a brothel in order that the young woman might support her in her old age. The daughter, whose name is illegible because of damage to the document, was murdered by Diodemus, an Alexandrian senator, for unknown reasons. Diodemus eventually admitted to the murder, and Theodora went before the court to demand that the senator be obligated to contribute to her subsistence. As she explained to the court: ‘For this reason I handed my daughter over to the brothel-keeper: that I myself might have food. Therefore, since I have been deprived of my support by my daughter’s death, I petition that a moderate amount, appropriate for a woman, be given for my support.’ The Egyptian prefect agreed; he banished Diodemus from the city and ordered that a tenth of his income be given to the old woman for her support.35 Theodora was certainly not unique; McGinn has noted that a primary reason for selling kin or the decision to enter prostitution was economic insecurity that resulted from low wages, limited opportunities for female work, stiff competition in the labor pool, disasters in family economics, and only occasionally the desire for quick social mobility.36

Dominic Montserrat has argued that because the daughter was able to give her elderly mother a percentage of her earnings, the daughter was probably not enslaved because she would not have kept her income if she had been a slave.37 This argument is unconvincing, because it was also common practice to allot slaves a certain percentage of their earnings for their own personal use, which was known as peculium, from which the daughter might well have supported her mother. Although we cannot be certain of the daughter’s legal status, the bigger issue of legal status and sexual exploitation merits consideration, because a trafficking victim of free status who was sold into a brothel at least had the possibility, however remote, of legal remedy for her predicament. As Orlando Patterson contends, ‘Non-slaves always possess some claims and powers themselves vis-à-vis their proprietor.’38 Legal recourse was denied to victims who were abducted, then legally enslaved, and then sold into a brothel. There were few ways out; the intermediary step of legal enslavement meant that abductees were shorn of any possibility of legal remedy to their enslavement and subsequent prostitution.

Early Christian emperors began to address the sale of dependents into prostitution in law beginning in the early fourth century. Constantine I (r. 312–337) dismantled and undermined the protections his pagan predecessors had put in place to protect freeborn children from wrongful enslavement and exploitation via sale or abandonment, presumably to bring Roman law into accordance with the reality of the Late Empire.39 Constantine’s actions would not survive the fourth century, however, because later emperors such as Theodosius I (r. 379–395) and Valentinianus III (r. 425–455) restored protections for children and moreover extended those protections to slaves, particularly where sexual exploitation was concerned. The latter two emperors decreed, ‘If fathers or masters, as pimps, should compel their own daughters or female slaves to sin, those same daughters and female slaves, after having sought the judgment of the bishop, shall be freed from every obligation of distress [presumably shameful acts performed under coercion].’40

In 343, Emperor Constantius II (r. 337–361) issued a decree that sought to suppress the sale of Christian women into brothels. Regardless of their original legal status, the women appear to have entered into servitude through their initial purchase, because once the sale had been concluded the rights of others to purchase the women from the brothel were restricted to ecclesiastics and Christian laymen, presumably in order to allow good Christian men to free their coreligionists from a life of or prostitution and shame,

If any man should wish to subject to wantonness the women who are known to have dedicated themselves to the veneration of Christian law and if he should provide that such women should be sold to brothels and compelled to perform the vile service of prostituted virtue, no other person shall have the right to buy such women except those who are known to be ecclesiastics or those who are shown to be Christian men, upon the payment of the proper price.41

The efficacy of such an edict is certainly questionable. The decree only applied to Christian women, and it did not address the plight of those women in brothels who were nonetheless forced to wait and hope for a Christian cleric or layman to purchase them from servitude and shame. While the edict theoretically limited the prof its accrued by brothel-keepers from the sale of Christian women by restricting the pool of potential buyers, the transaction was nevertheless permitted.

Under Justinian I (r. 527–565), the imperial campaign to suppress the prostitution of dependents reached its height. In 529, Justinian outlawed the enslavement of foundlings and abandoned children, a practice that also provided major sources of sex workers in brothels, inns, and taverns according to late antique social commentators.42 The plight of sex workers in Constantinople appears to have left a lasting impression on the emperor, for in the early 530s Justinian commissioned an inquiry into the sex industry of the Byzantine capital; unsurprisingly, the commission found that the slave trade remained deeply enmeshed in the commercial sex trade.43 In 535, its findings were published in Novella 14, which describes in detail human trafficking operations. The imperial commission reported,

We have learned that men who live dishonestly, have in various cruel and detestable ways found the occasion of making money by nefarious means, in that they travel about in the provinces and in many places, deceive poverty stricken girls, ensnare them by promising them shoes and clothing, bring them to this city, confine them in their own lodging places, feed and clothe them scantily and offer them up to anyone’s pleasure; that they take the evil income from prostituting the bodies of the girls; that they take a written promise from the latter, compelling them to perform such impious and abominable service for him as long as he pleases; and that some have even demanded sureties for the girls […] Some of them have been so wicked as to induce girls less than ten years old to commit dangerous debauchery.44

Poverty continued to provide opportunities for traffickers to lure young women and children into sex trafficking networks. By promising to alleviate material needs such as food, clothing, and shelter, traffickers were able to take advantage of young people’s dire circumstances and entice them to Constantinople. Once in the city and effectively isolated from their kinship networks, the young women and children were then at the mercy of traffickers who profited from their coerced prostitution. The report indicates that trafficking networks were highly organized and implicates minor bureaucrats in their operations. Traffickers apparently worked in conjunction with partners such as brothel-keepers and pimps, as well as corrupt local officials, and as a result they were able to secure both enforceable written contracts obligating the girls to labor for their abductors and sureties from third parties for the abductees.

Traffickers took steps to protect and secure their possessions. Marriage, one of the few escapes for the young women, was expensive, strictly controlled, and thus highly discouraged. The commission reports,

And so impious and unlawful are the acts committed in our times, that when some people, moved by pity, have wanted to remove such women from such occupation, to enter into lawful marriage with them, the panderer would not permit that to be done […] Thus some men have had difficulty, and only upon giving large amounts, to redeem such girls, to enter into a lawful alliance with them.45

Constantinople was at the heart of regional and long-distance trafficking networks that spanned the Mediterranean, the Levant, and Eastern Europe. Earlier the report had noted that traffickers had sought out women and children in the provinces and lured them to the capital city with promises of material support to alleviate their poverty. However, the recruitment and abduction of victims was not only a provincial problem. Traffickers maintained overseas connections through which abductees were transported between the environs of Constantinople and the outlying provinces, indicating once again that for women and children the slave trade and sex trafficking had merged. The commission continued,

The matter has gone to such an extent that such lodgings are found all over the city and in places across the sea and what is worse, even close to sacred places and venerable churches […] And there are a thousand ways, not easily enumerated in an oration, by which this cruel evil [sex trafficking] has grown to large proportions; so that while it was formerly present in only a few places in this city, it, and all the places surrounding it are now full of it.46

Justinian responded forcefully to the commission’s findings by outlawing fraud, deception, and coercion of children and young women into the sex trade, although we may debate the practicality of enforcing such a ban. He nullified any contract obligating women to labor for their abductees, and further threatened pimps, procurers, and their partners with corporal punishment and banishment from the city and its hinterlands: ‘If anyone hereafter takes a written promise or surety, he will have no benefit therefrom, since the surety will not be bound, the written promise shall be void, and the person taking them will be punished corporally, as stated before, and expelled far from this city.’47 To give the crackdown added weight, he put the urban praetors in charge of enforcement, and threatened that those caught traff icking thereafter ‘[would] be arrested by the worshipful praetors of this fortunate city and visited with the most extreme penalty,’ while a person caught using their home in cooperation with traffickers as illegal brothels for coerced prostitution ‘[would] be punished by a fine of ten pounds of gold and [run] the risk of losing his house.’48

The commission’s findings quoted at length in Novella 14 support the observations of the sixth-century Greek chronicler John Malalas (c. 490–570), an educated jurist who received his formal training in Antioch and then later moved to Constantinople in the late 530s or early 540s. Malalas tells us in his Chronographia that in the early 530s, even as the imperial commission into the sex industry was continuing apace,

Those known as brothel-keepers used to go about in every district [of Constantinople] on the lookout for poor men who had daughters and giving them, it is said, their oath and a few nomismata [coins], they used to take the girls as if under contract; they used to make the girls into public prostitutes, dressing them up as their wretched lot required and, receiving from them the miserable price of the bodies, they forced them into prostitution.49

Similar themes emerge from both the Chronographia and Novella 14: the poverty of the victims, for example, and the deception, fraud, and coercion of the traffickers. By specifically seeking and targeting poor families, traffickers enticed impoverished parents into selling their children’s labor for small sums of money, and through deception, they allayed real parental fears of enslavement and prostitution by swearing false oaths (presumably to protect their children and to return them after the end of the contract terms). Once beyond the protection of their kinship networks, the children were then forced into sex work.

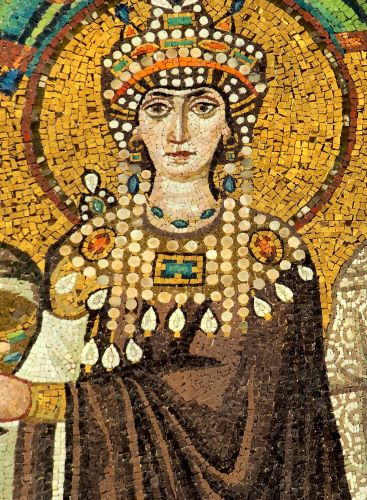

Justinian’s efforts to suppress human trafficking in Constantinople were complemented by those of his wife, the Empress Theodora (r. 525–548), who had begun her own official inquiries into sex trafficking in the capital city, which it seems ran parallel to the imperial commission’s investigations. Theodora was intimately familiar, from personal experience, with the plight of sex workers in Constantinople during the early sixth century. She had been born to an unknown woman who worked as a dancer and an actor; both occupations were closely associated with sex work in Late Antiquity. Theodora herself, following in the footsteps of both her mother and her elder sister Komito, became an actress and a dancer, and quite possibly a sex worker, in one of Constantinople’s many brothels in the early 520s.50 Her talents eventually caught the eye of Emperor Justinian himself, who fell in love with her. The two married in 525, and Theodora became Empress of the Byzantine Empire and by all accounts a queen of considerable energy, political acumen, and determination. During Theodora’s investigations into the sex industry, John Malalas tells us that,

She [Empress Theodora] ordered that all such brothel-keepers should be arrested as a matter of urgency. When they had been brought in with the girls, she ordered each of them to declare on oath what they had paid the girls’ parents. They said they had given them five nomismata each. When they had all given information on oath, the pious empress returned the money and freed the girls from the yoke of their wretched slavery, ordering that henceforth there should be no more brothel-keepers. She presented the girls with a set of clothes and dismissed them with one nomisma each.51

In this account, the Empress demonstrates her knowledge of sixth-century Byzantine human trafficking. Theodora’s interrogation of the brothel-keepers opens with the presumption that they had paid impoverished parents for their children. It appears odd that the Empress would then reimburse traffickers for the money that they had paid for the children, but as the imperial commission reported, enforceable written contracts were regularly drawn up and notarized by corrupt minor officials, which obligated the girls to labor for their abductors. We may presume that the payments legitimized the girls’ freedom and ensured that traffickers could not attempt to reclaim them later by invoking legally binding contractual obligations, at least until Justinian addressed those legal obligations directly by nullifying the contracts.

The Empress then off icially freed the girls from their obligations to their pimps, which Malalas unequivocally equates with ‘wretched slavery,’ and she pointedly addressed their poverty by ensuring the girls had clothes and a small amount of spending money before they were set free. Moreover, Theodora also took steps to prevent their later relapse into sex work due to coercion or extreme deprivation by creating support structures designed to address the uncertainty in the lives of survivors. Procopius (500–565) tells us in his work, On Buildings, that because ‘there had been a numerous body of procurers in the city [Constantinople] since ancient times, conducting their traffic in licentiousness in brothels and selling others’ youth in the public marketplace and forcing virtuous persons into slavery,’ Justinian and Theodora converted and expanded a palace into a large, well-appointed monastery with a sizable endowment to house those women and children who had been forced to work in brothels, ‘not of their own free will, but under the force of lust,’ because of deprivation. Procopius goes on to relate in lofty rhetoric, ‘They [Justinian and Theodora] set free from a licentiousness fit only for slaves the women who were struggling with extreme poverty, providing them with independent maintenance [i.e. an endowment], and setting virtue free.’52

Yet despite the intense pressure that the royal couple applied to human trafficking networks in Constantinople, the Empire would not sustain suppression efforts indefinitely. The Byzantine military itself had become a major trafficking organization by the eighth century, and slaving continued in the Eastern Mediterranean into the Early Modern Period.

Thus far we have primarily considered the Mediterranean of Late Antiquity and the early Middle Ages, since the bulk of extant evidence pertains to this region and these periods, but there is evidence for similar conditions of exploitation in trafficking networks in the West formerly under the control of Rome. Examining the conditions that trafficking victims experienced is more difficult in the West, not because the situation was any more humane, but because of the dearth of extant source material. The sexual violence against slaves and trafficking victims and their exploitation and prostitution only occasionally surface in the surviving sources. In early medieval Europe, Ruth Mazo Karras has argued that ‘the symbolic power of the enslavement of women came from their sexual use rather than from the imposition of forced labor or other servile treatment.’ Like Jennifer Glancy’s observations of the gendered experience of slavery in Late Antiquity, Karras observes that men and women in early medieval Europe also experienced slavery differently: although both felt the humiliation of their loss of rights and personal autonomy, the sting of their loss of honor, and the sorrow of their loss of kin, female slaves were much more likely than male slaves to experience sexual violence, even if they were not purchased primarily for sexual labor.53 Although scholars have observed that, for the most part, royal decrees and ecclesiastical councils forbade the sexual exploitation and prostitution of slaves, nevertheless the extant evidence, thin as it is, suggests both that these prohibitions were mainly honored in the breach,54 and that the violation and exploitation of abductees caught in trafficking webs were widespread and commonplace. In cases where sexual violence is explicitly noted, the victims are, almost without exception, women and children. This trend partly reflects tropes of atrocities that were standard and expected in ecclesiastics’ moral diatribes against violence done to civilian populations in general, and to Christian communities in particular, but it also reflects a social concern over blurring the distinction between slave and free bodies. Still, there is a reason that the violation and exploitation of slaves and abductees became tropes in the first place.

In the British Isles at the end of the fifth century, Patrick blasted Coroticus for his role in the trafficking of newly baptized women and children into Ireland and into the lands of the Picts: ‘You [Coroticus] would rather kill or sell them on to a far-off tribe [the Irish or the Picts] who know nothing of the true God. You might as well consign Christ’s own members to a whorehouse […] You gave away girls like prizes, not yet women but baptized.’55 In Kent, the early seventh-century law code of Aethelbert penalized the sexual exploitation of female slaves with varying fines, the amounts of which depended first and foremost on the status of their owners. The violation of a slave woman belonging to the king carried a fine of 50 shillings, of a slave woman belonging to a nobleman, 20 shillings, and of a slave woman belonging to ceorl, six shillings.56 According to the Penitential of Theodore, the sexual exploitation of an enslaved woman (ancilla) was a relatively minor offense compared to other adulterous transgressions. If a slaveholder committed adultery with his slave woman, then the penitential recommended a penance of only six months for the slaveholder and the manumission of the slave woman (liberet eam), although the slaveholder was under no compulsion to free her. If, however, the woman was freeborn, then the recommended length of penance increased from months to years, the exact number of which varied according to her social and legal status.57

On the Continent in the early 730s, King Liutprand of the Lombards (r. 712–744) took steps to curb the prostitution of family members and kin by outlawing the coerced prostitution of female wards in 731.58 Two years later in 733, he heard a case involving a husband who stood accused of prostituting his wife and decreed that if the wife voluntarily went along with the scheme, she was to be executed, her husband was to pay her family a wergild equal to the penalty that would be owed if he had killed her in a brawl, and the man who lay with her was to be enslaved and handed over to the family of the woman. If the woman refused her husband’s attempts to prostitute her, then the husband was to pay her 50 solidi for giving his wife ‘evil council’ (malum consilium).59 The prostitution of kin in eighth-century Italy might well have been an economically viable strategy for families struggling to make ends meet, because according to Boniface in his letter to Cuthbert of Canterbury (d. 760) in 747, the roads to Rome were lined with brothels that were staffed by English nuns who never completed their pilgrimage to the Eternal City, but instead had run out of funds and were forced to prostitute themselves.60 Boniface meant to discourage nuns from making the dangerous trip to Rome by encouraging a synodal prohibition on such journeys, and thus we may expect exaggeration. Nevertheless, he presents an image in which prostitution continued to be a thriving business along eighth-century trade routes and a reliable means of relieving economic deprivation.

The Annals of Fulda, however, return us once again to the overt sexual violence involved in human trafficking during the tumult of the ninth century. According to the Annals, in 894, the Magyars ‘killed men and old women, and carried off the young women alone with them like cattle to satisfy their lust and reduced the whole of Pannonia to a desert.’61

Across the Northern Arc during the ninth and tenth centuries, the experiences of women and children fused human trafficking, sex trafficking, and enslavement. Hoskuld bought Melkorka as a concubine from Gilli the Russian in Laxdaela Saga. Landnamabok tells us that in the late ninth century, a Viking named Helgi raided Scotland and captured Nidbjorg, the daughter of a minor Norse king in Scotland, and made her his wife.62 In late ninth-century Iceland, the Viking Ketil, son of Thorir Thidrandi, bought Arneid, the daughter of Earl Asbjorn Skerry-Blaze (d. 874), from a fellow Icelander named Vethorm for double the price Vethorm had originally paid for her. Vethorm had come into possession of Arneid from his son and his nephew after they had killed her father and enslaved her. After Ketil bought Arneid, he then made her his wife.63 On the eastern reaches of the Northern Arc, Ibn Fadlan observed the exploitation of enslaved women among the Vikings in large wooden houses that served as communal shelters on the banks of the Volga River, from which they traded with merchants moving along the river. He tells us,

With them [the Viking men], there are beautiful slave girls for sale to the merchants. Each of the men has sex with his slave, while his companions look on. Sometimes a whole group of them gather together in this way, in full view of one another. If a merchant enters at this moment to buy a young slave girl from one of the men and finds him having sex with her, the man does not get up off her until he has satisfied himself.64

In early eleventh-century England, Wulfstan I, Archbishop of York, excoriated the exploitation and abuse inherent in human trafficking networks in his Sermo Lupi ad Anglos,

And it is shameful to speak of what has happened too widely, and it is terrible to know what too many do often, who commit that miserable deed that they contribute together and buy a woman between them as a joint purchase, and practice foul sin with that one woman, one after another, just like dogs, who do not care about filth, and then sell for a price out of the land into the power of strangers God’s creature and his own purchase, that he [God] dearly bought.65

In Wulfstan’s telling, the economic, transactional nature of human trafficking is central to the dehumanization and commodification of human beings that allows such violence to be perpetrated upon abductees without guilt or shame on the part of the perpetrators. The women were bought from human traffickers, abused and exploited, and then sold back to human traffickers for sale in other lands across the Northern Arc and presumably into the same fate. Wulfstan was not alone in observing centrality of commodification in the dehumanization of trafficking victims. Richard of Hexham described the fate of women and children kidnapped from the borderlands between England and Scotland, who were then enslaved, exploited, and sold or traded for cattle after the Battle of Clitheroe in 1138.

On the Continent in the eleventh century, Adam of Bremen tells us that the Danes, ‘in contrary to what is fair and good,’ had a custom of ‘immediately selling women who have been violated.’66 Although Adam evinces strong anti-Scandinavian prejudices throughout his ecclesiastical history, in this instance his laconic description does not deviate significantly from the general picture of the other examples noted. In this particular instance, however, it is unclear if the women were rape victims who, after being dishonored, were then sold into slavery by their families, or if these were women who were raped and then sold on to other owners by their attackers in a manner reminiscent of Wulfstan’s Sermo,or if perhaps Adam was referring to both sets of circumstances.

Farther to the east, in the Baltic in the thirteenth century, Henry of Livonia (f l. 1225–1227) reports that in 1226, a papal legate witnessed a group of traffickers from the Isle of Oesel entering the port of Dunamunde on the shores of the Gulf of Riga, just west of the town of Riga. The Oeselian traffickers were returning from Sweden with the spoils of their raids and ‘a great many captives.’ He tells us that while the Oeselians were ‘accustomed to visit many hardships and villainies upon their captives,’ women and girls could expect rape and concubinage. ‘Both the young women and virgins, at all times [the Oeselians visited hardships upon them], by violating them and taking them as wives, each taking two or three or more of them. The Oeselians were even accustomed to sell women to the Kurs and other pagans [indigenous Baltic peoples].’67 Henry, in all probability a cleric who came to Livonia in the early thirteenth century from northern Germany, was well positioned in Livonian society as a member of the household of the ranking ecclesiastic in the Baltic, Bishop Albert, and was therefore likely to be well-informed of major trade and trafficking trends in Riga and abroad. Nevertheless, Henry also evinces strong anti-pagan biases in his Chronicle, like so many Christian chroniclers of his day, so we cannot say that this behavior was unique among the pagans or more specifically among the Oeselians. The major theme, however, is yet again emphasized: all victims of traffickers could expect violence and abuse, but for women and children sexual exploitation was a constant further threat to endure.

The above examples are by no means exhaustive, but they should suffice to demonstrate that while men were certainly exploited and abused, for women and children the slave trade and the sex trade were effectively amalgamated. Rebecca Flemming argues that we must recognize that there are important formal differences between slaves and sex trafficking abductees in that institutionalized slavery is officially recognized and legal, and therefore the weight of the state preserves slavery as a social institution. Even modern-day trafficking victims at least theoretically have recourse to legal remedies, and even if those legal remedies are distant and remote, the possibility of rescue and relief is of no small consideration. She muses that, ‘Indeed, the overall effect of the argument that prostitution inherently imitates slavery is to blur this distinctiveness, to overlook the fact that the relationship between prostitutes and slaves may actually be one of identity not resemblance.’68 I argue the opposite. The relationship between slaves and prostitutes, at least for those abductees who became either or both through human trafficking activity, is in fact one of uncanny resemblance based upon their shared physical, corporal daily experiences, in which legal recourse was denied to slaves and remote enough for sex trafficking victims as to be little more than a distant, pale hope. Although identity is certainly an important aspect of their relationship – because hope, however distant, is still possible for abductees and not for slaves – lived experience is the defining characteristic of the slave/sex trafficking abductee relationship, not identity. Although the abductees of late medieval sex traffickers in Western Europe were not slaves in the strict legal sense, it made little physical difference in their daily lives.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Chapter 3 (143-166) from Human Trafficking in Medieval Europe: Slavery, Sexual Exploitation, and Prostitution, by Christopher Paolella (Amsterdam University Press, 10.05.2020), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.