Examining medieval attitudes toward children in the social anomaly of the saintly child.

By Dr. David F. Tinsley

Professor Emeritus of German Studies

University of Puget Sound

Introduction

Even the most cursory survey of scholarship on medieval childhood would lead one to conclude that the only task remaining for opponents of Philippe Aries’ thesis—”a concept of childhood did not emerge until the early modern period” — is to compose a suitable epitaph. Nicholas Orme is but the most recent scholar of medieval childhood to challenge Aries, when he asserts that “adults regarded childhood as a distinct phase or phases of life; that parents treated children like children as well as like adults, that they did so with care and sympathy, and that children had cultural activities and possessions of their own.”1 Albrecht Classen’s wide-ranging and thoughtful introduction to this volume culminates in the conclusion “that the paradigm established and popularized by Philippe Aries… now can be discarded” (46). Clearly, as Classen notes, a paradigm shift in our understanding of medieval childhood is almost complete. Yet in rejecting Aries’ thesis, most scholars have not gone so far as to proclaim medieval and modern notions of childhood to be identical. So scholars of medieval mentalities now face the challenge of resetting the boundaries between medieval and modern notions of adulthood and childhood. And when all is said and done, it is my belief that some aspects of alterity will survive.2

Medieval mentalities differ most substantially from those of the modern, secular West in their consistent validation of divine presence in human existence. Such validation took on both a diachronic and synchronic dimension, in the form of salvation history on the one hand and sainthood on the other. The medieval apocalyptic imagination engendered cycles of anxiety regarding the imminent end of time, the acuteness of which our modern sensibilities can scarcely imagine.3 Medieval assumptions regarding the omnipresence of the Divine were personalized in the universal veneration of the saints. Saints were seen as “persons who are leading or have led a life of heroic virtue.”4 The presence of the Divine is validated by superhuman actions in the areas of asceticism, contemplation, and action, and by verifiable miracles and visions.5 The power to convert and to heal extended beyond the grave; cults surrounding saints’ relics indicate that their posthumous healing powers were seen as harbingers of salvation.6 The records of saints’ lives and miracles in the form of hagiography comprised the most popular literary genre of the Middle Ages. Given this popularity, one can assume a basic familiarity of medieval audiences with the lives of the saints. In the following pages I shall use the examples of saintly children drawn from hagiography to examine medieval attitudes toward children in general, as reflected in a literary portrait of the social anomaly of the saintly child.

Reading a Middle High German literary text as a mirror of historical attitudes toward children requires meticulous attention to the limitations of genre on the one hand and the expectations of the intended audience on the other. As Albrecht Classen reminds us, “Literary texts do not allow a straightforward interpretation determined by socio-historical, anthropological, and mental-historical criteria” unless scholars remain acutely sensitive to “the specific nature and informational value of narratives” (Classen, 3)7 Even scholars of “mentalite,” who deny to medieval literature the status of historical documentation, proceed cautiously when employing saints’ lives as sources for historical attitudes.8 Hagiographers were, after all, more concerned with spiritual than with chronological growth. More often than not, as Goodich points out, “the early years are given in the barest outline.”9 Goodich’s statistics would also seem to indicate that saints’ lives offer a less than promising source for studying medieval notions of childhood: “Of the over five hundred saints who became the objects of local or universal cults from 1215 to 1334, perhaps no more than ten percent possess reliable data concerning their early years.”10 Furthermore, as Siegfried Ringler has argued in his studies of the Dominican Sisterbooks of the fourteenth century, it is problematical to use any statements contained in hagiographical or mystagogical literature as evidence for reconstructing historical reality, however one might define it. In denying that the stories of the Sisterbooks reflect the reality of fourteenth-century Dominican life, Ringler sees these texts consisting in “motifs, sets of images, accounts of miracles and visions, and of special instances of God’s grace that have been, either consciously or subconsciously, taken from earlier literary sources.”11 When examining hagiographical sources, then, one must consider the possibility that one is dealing with “stock literary weapons of the hagiographers or retrospective justifications for greatness.”12

Paradoxically, the nature of sainthood itself makes the few surviving accounts of saintly childhoods a surprisingly rich source for medieval notions of normality. By definition, sainthood finds expression in transcending human limits and the resulting violation of social norms. And if one has the need to document the saintly nature of an individual, inevitably such abnormal behavior is seen to begin in the early years. These descriptions of saintly children’s behavior are frequently contrasted with how normal children behave. The beloved topos “quasi senex” or “puer senex,” as employed in the vita of Hedwig of Poland provides just one example. “From the time she was a small child she had the demeanor of an old woman, trying as an old person would to practice good morals, and to flee the inconstant lifestyles and insolence of other children.”13 A more detailed example may be found in Athanasius’ portrait of the young Antony:

He could not endure to learn letters, not caring to associate with other boys; but all his desire was, as it is written of Jacob, to live a plain man at home. With his parents he used to attend the Lord’s House, and neither as a child was he idle nor when older did he despise them; but was both obedient to his father and mother and attentive to what was read, keeping in his heart what was profitable in what he heard. And though as a child brought up in moderate affluence, he did not trouble his parents for varied or luxurious fare, nor was this a source of pleasure to him; but was content simply with what he found nor sought anything further.14

When we assess saintly behavior in such cases, we infer medieval expectations of normal childhood by observing what saintly children do not do. Antony is abnormal in his desire for solitude, in his willingness to stay at home, in his industriousness, in his respectful treatment of his parents, in his attentiveness to the holy word, in his ability to retain knowledge, in his lack of interest in material possessions, and in his moderation. From this one may conclude that expectations of normal children or at least boys would have included always wanting to be with their friends, being away from home, idleness, disobedience and disrespect, in attentiveness, lack of interest in church, prodigality, and dissatisfaction. We may infer from the “vita of Hedwig” that one expected children to be immoral, to practice inconstant lifestyles, and to be insolent to their elders. This correlates with the results from Goodich’s study, where bad habits ascribed to children include “love of games and other vain pursuits, absentmindedness, pettiness, putting, shamelessness and changeability.”15 Lest one object that these examples are drawn from saints’ lives written before the Middle Ages and therefore do not necessary reflect medieval notions of childhood, one can find many similar examples from the legends of medieval men and women. Not only that, but the proliferation of hagiography in the manuscript record indicates that such depictions of saintly and normal childhood were among the most popular objects of literary consumption in the European Middle Ages.

Such exemplary abnormality or saintliness should be differentiated from what one might call supernatural abnormality, characterized by superhuman feats made possible by the infusion of the Holy Spirit. The vita of St. Nicholas, the patron saint of children, contains several examples of such saintly precociousness.

On the first day of his life, as they wanted to bathe St. Nicholas, the child stood up in his wash basin. He also freely chose not to nurse at his mother’s breast on Wednesdays and Fridays, not once. When the child was older it separated itself from the things that other young people took pleasure in, choosing instead to go to church with great devotion and whatever he understood there of the holy scriptures, er earnestly maintained in his memory.16

Nicholas displays here the power to stand when he is a day old, he demonstrates a willingness to fast as a nursing infant, and as a young boy he can understand scripture than many adults struggle to comprehend. Here saintly virtue is not set against normality, but rather extraordinary power is depicted in the moment it emerges from the helplessness universal to all human infants.

Whenever such saintly precociousness surfaces, it has serious social consequences, especially for parental authority. As Mary Dzon shows elsewhere in this volume, challenges to authority extended even to the Holy Family, as “apocryphal narrators imagined the interaction that took place between the boy Jesus, his parents, and their Jewish neighbors.” The frequency of conflict in Middle English adaptations of the fifteenth-century apocryphal text Liber de infantia salvatoris allows Dzon to reconstruct considerable interest among audiences of vernacular religious literature for such topics. She documents speculation about Jesus’ childhood before his entry into public life in both literature and iconography dating back to the twelfth century. The Anglo-Norman Holkham Bible depicts Jesus doing chores for his parents, while Dzon also cites the twelfth-century tale of Aelred of Rievault concerning Jesus’ consideration of the needs of his mother and his nurse. Susan Marti’s study of the Engelberg codices cites numerous apocryphal accounts of Jesus’ childhood in both vernacular and Middle Latin texts of the 12th and 13th centuries.17 Of special interest to my study are the stories from the cycle that highlight conflicts between paternal authority and Jesus’ higher calling. Apparently the incongruity inherent in Joseph’s attempts to raise a divine son was the object of considerably audience interest throughout the Middle Ages.

Weinstein and Bell show how similar themes of generational conflict proliferated in the hagiography of the thirteenth and fourteenth century. Such “childhood crises” are documented in “every country of Europe,” they are “not limited to a particular religious order” and they extend to every social class.18 From hagiographical tales of social and family conflict, Weinstein and Bell draw inferences that clearly contradict Aries: “Medieval adults expected children to behave in certain ways and to go through certain stages of development. Parents were intensely involved with their children’s upbringing and concerned with their welfare. They reared them in accordance with their station and conscientiously tried to prepare them for life tasks. Even if they designated their children for a life in religion, they had socially conventional notions of what that kind of life entailed. They felt love for their children and expressed their affection and concern with praise and with punishment.”19 Such concerns with praise and punishment could be put to the test whenever a child sought a higher calling through the power of the spirit. “A family that had a saintly child was likely to be put under great strain, even to the breaking point, particularly if the child was a girl.”20 In these latter cases, conventional notions of childhood may be inferred not only from negative and positive extrapolations of saintly abnormality, but also from the sanctioning or punitive responses of parents.

In the following section I shall analyze a vernacular didactic tale composed for a courtly setting in which such a “childhood crisis” occupies one of two parallel plot lines. The aim will be to re-imagine the response to such a text of a courtly audience well-versed in hagiography.21 My intertextual reading will transpire according to the categories developed in the previous section, in particular notions of normality which may be inferred from the behavior of saintly children and parental prohibitions as described in hagiography. Conventional hagiography sought in its documentation of selfless conduct and posthumous miracles the ultimate vindication of papal imprimatur. Descriptions of saintly children serve as retrospectively presented harbingers of holiness for the reader/listeners accustomed to hearing how a character like Moses in the Old Testament to prefigure the coming of Christ. Depictions of a saint’s childhood tend to describe it in two phases: childhood and adolescence, the first of which was devoted more to precociousness, the second more to vocation.22

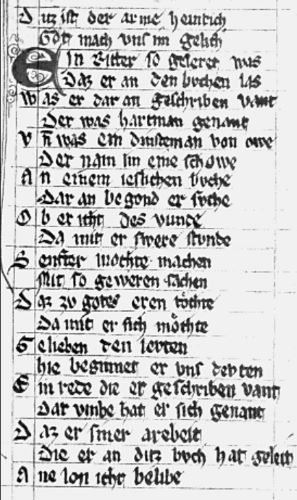

The Saintly Child as a Source of Conflict in Hartmann von Aue’s ‘Der arme Heinrich’

I now turn to the didactic tale Der arme Heinrich (“Poor Henry”), written in Middle High German by the twelfth-century ministerialis Hartmann von Aue.23 “Poor Henry” is not a saint’s life, but it is germane to our study of childhood because Hartmann uses the motif of the healing bath in children’s blood from the Silvester legends and the child-sacrifice story from the Engelhard accounts that Classen analyzes in our introduction in order to explore the saintly childhood as a social problem.24 In Hartmann’s tale the question of saintliness is left open to interpretation by the child’s parents, and, in turn, by Hartmann’s reader/listeners. Hartmann explores saintliness as a possibility, and he clearly expected his audience to make their judgments regarding the status of his peasant virgin heroine based upon their familiarity with extraordinary behaviors common to hagiography.25

Der arme Heinrich tells a cautionary tale of sin and repentance as depicted in two lives, the knight Sir Heinrich of Aue and a peasant girl whom he encounters on one of his feudal estates. Sir Heinrich is a noble knight of splendid reputation who enjoys all the advantages of courtly life, only to be struck down by leprosy26 and condemned to a life of suffering and social ostracism.27 After traveling to Salerno to seek a conventional cure, Heinrich abandons his quest when he learns that the only possible treatment requires the blood of a girl of marriageable age who would willingly sacrifice herself for him. Convinced that no such person could ever be found (“It is so impossible that anyone would willingly suffer death for my sake. For this reason I shall have to bear this scandalous and awful fate until I die,” 453-57),28 he retires to spend his final days on the land of one of his peasant overseers.29 The audience would have seen the noble Heinrich seeking refuge with a peasant family, however prosperous, as the final sign of his fall. The hand of God humbles him, taking him from the elite circles of Swabian courts to the rustic isolation of a rich peasant’s abode in the wilderness.

In the throes of disgrace and despair, Heinrich makes the acquaintance of the second protagonist, the eight-year-old daughter of the Meier.30 The peasant girl’s very first reaction sends a powerful signal to the audience of her extraordinary potential. Even as others shun Henry’s hideousness, with its disfigurement a certain sign of sin and evil,31 she seeks him out. (“She devoted herself with all the goodness of an innocent child to her Lord, so that she could be found at any time at his feet. With touching devotion she attended to her Lord, and he came to love her, too” (321-25).32 The relationship that develops between the noble knight and the peasant maiden during Heinrich’s exile has few precedents in medieval literature and certainly would have captured the attention of Hartmann’s audience. It has usually been read against vernacular literary sources as a kind of playful take on courtly love using motifs from Minnesang,33 Heinrich rewards her goodness and devotion with a number of gifts, including mirrors, hair bands, belts and rings. She is drawn to him, the narrator explains, because children can be easily swayed by gifts (334-35). This added bit of information supports the inference that a maiden would not achieve a “heimlich” (intimate) relationship with a knight, unless she were so young as not yet to be susceptible to such gifts. And indeed her steadfast devotion and service bring Heinrich to the point that he playfully terms her his “gemahel” (wife or bride, 341).

This “courtship” takes on an different aspect when read against hagiography. The narrator sends a signal to the audience that they may judge her according to saintly forbears when he reminds the audience that more than the desire for gifts motivates the Meier’s daughter: It is above all her “süezer geist” (her virtuous spirit) which is “gotes gebe” (a gift from God, 348). The reference to the daughter’s divine gifts stands in contrast to the worldly wealth and eroticism symbolized by the ring, the mirror, and the girdle. Indeed, similar gifts or the promise of the same from a “suitor” to an innocent young maiden are a common motif from the lives of virgin martyrs such as Agnes. “He promised her jewels and great wealth if she consented to be his wife.”34 Given Heinrich’s “fallen” status in this stage of the tale, a hagiographical reading would see the courtship in terms of temptation. The possibility that the audience would place Heinrich into the role of the “pagan” suitor also explains the narrator’s frequent asides meant to reassure the audience of the Meier’s daughter’s virtue, despite her lowly station. No fewer than five separate references stress her tender age, goodness and innocence.35

The Meier’s daughter hears by accident of Heinrich’s fate and the possibility of a cure on earth. Three years have passed. She is now mature enough to marry (“vollen manbaere,” 447), as the sacrifice demands. Her compassion erupts in the form of silently violent weeping. Her tears flow so strongly that they drench the feet of her parents, at the foot of whose bed she is sleeping, and awaken them. The association of tears, compassion, and feet would have signaled a spiritual potential beyond goodness to almost any medieval audience. They would have thought of Mary Magdalene, who according to medieval exegetes was the woman who washed the feet of Jesus with her tears and dried them with her hair. Magdalene was for the Middle Ages the ultimate penitent saint, whose spiritual journey brought her from whore and outcast to becoming the disciple of the disciples.36 Her legend, with which the audience would have been familiar, tells of her long life after the crucifixion, which includes miraculous acts of healing and divinely inspired preaching. No other legend so embodies the power of sainthood to raise one above the restrictions of gender, wealth, and social class. And among the most convincing evidence of saintliness is the willingness to sacrifice oneself for others and the ability to make miraculous cures possible. The peasant girl’s tears are another powerful signal to the audience that it needs to see her as a potential saint.

Lest the audience miss such a clear signal, the narrator addresses directly the possibility of saintliness in several commentaries. The narrator initially marvels at the girl’s presence in the company of a leper (He seemed to her to be free of sin and healthy. However much the playthings that he had given her might have moved her, she was motivated above all by the gift God had given her: a good heart [344-48]).37 He describes the Meier’s daughter’s seated position with Heinrich’s feet in her lap in terms that compare her to the angels (For the sweet little thing had the feet of her dear lord in her lap. One could easily compare her childlike devotion to the goodness of the angels [461-66]).38 When she bathes her parents’ feet in tears, the narrator calls it an example of the greatest compassion that he had ever heard displayed by a child (She prepared again a bath with her crying eyes, for she bore hidden in her feelings the highest degree of goodness that I have ever heard a child to possess [518-23]).39

The centerpiece of Hartmann’s didactic tale is the dispute between her and her parents in response to the announcement that she plans to sacrifice herself for Heinrich (550-1010). The parents’ arguments, such as that she is just a child (573-75), she does not realize how terrible death is (578-584), she should obey the 4th Commandment (640-46), or that suicide will consign her to eternal damnation (658-62) are predicated on the assumption that their daughter is a normal child. In this sense Classen is justified in reading the words of the mother as an expression of maternal love (See Introduction). The daughter’s lengthy and eloquent response combines a strong dose of contemptu mundi (“Life brings nothing but toil and suffering” [601-04])40; “our youth and life are nothing more than ashes and dust” (722-23)41, and “marriage is hell on earth” (765-72)42 with spiritual fervor (If she gives herself to God early, then she shall escape the threat of the devil [684-90])43; she is giving freely giving up her worldly life for eternal life (606-10]).44 Such lofty aspirations are not only incongruous in the mouth of an eleven-year-old peasant girl, they also appear to invoke the selflessness of sainthood. And since one of the typical early signs of sainthood is the rebellion against parental authority in favor of total devotion to God, the audience would certainly have continued to weigh the possibility that the girl’s motives were truly divinely inspired. The girl’s mastery of rhetoric would have called yet another parallel to the audience’s mind: St. Catherine of Alexandria’s dispute with the fifty philosophers assembled by Prince Maxentius, where she puts all of their erudition to shame. The wisest sage replies, “You must know, Caesar, that no one has ever been able to stand up to us and not be put down forthwith; but this young woman, in whom the spirit of God speaks, has answered us so admirably that either we do not know what to say against Christ, or else we fear to say anything at all.”45

The impassioned plea of the Meier’s daughter reaches its climax when she contrasts the hell on earth of marriage with the heavenly liaison promised her by Christ, whom she depicts as a free peasant bridegroom whose fields are in perpetual blossom. The Meier’s daughter’s eloquent description would be in itself compelling evidence of spiritual inspiration. Her evocation of the Peasant Bridegroom provides an even clearer sign to the medieval audience that the question of her sainthood stands at center stage. Anyone familiar with saints’ lives would have recognized how much the peasant girl’s words mirror the response of St. Agnes to the gifts and proposal of the precept’s son.46 And it is certainly no accident that Agnes’ vita begins with the “quasi senex” topos (“Childhood is computed in years, but in her immense wisdom she was old; she was a child in body but already aged in spirit.”)47 After telling the prefect’s son that she is already pledged to another, Agnes commends this mystery lover for nobility of lineage, beauty of person, abundance of wealth, courage, the power to achieve, and love transcendent. “The one I love is far nobler than you, of more eminent angels; the sun and the moon wonder at his beauty; his wealth never lacks or lessens, his perfume brings the dead to life, his touch strengthens the feeble, his love is chastity itself, his touch holiness, union with him, virginity.”48 The peasant girl’s description is not as overtly allegorical because it is meant to contrast the joys of heaven with the miseries of life on earth, but both she and Agnes stress the enduring power of the divine. The Meier’s daughter’s peasant bridegroom is free, that is, he is under feudal obligation to no one like Heinrich, something that defines the precariousness of even a wealthy peasant such as that of the Meier must live. His plough, she asserts, brings prosperity (779). Neither do animals die nor children cry (780). His holdings are never touched by frost, no one goes hungry, there is no suffering and no illness. (783-86).49 Through the bridegroom reference, Hartmann is able to evoke the legend of Agnes and thereby forge an explicit link to the potential of mystical experience within the Meier’s daughter’s striving.50

The peasant girl’s parents now face an agonizing decision. Is their daughter truly saintly with the potential to become a virgin martyr or is she merely a foolish young girl who should be thoroughly beaten and sent back to work? In their search for an answer they look to the same sources that Hartmann’s narrator has been invoking all along: the lives of the saints.

When they saw their child approach Death in such a fashion, and when she spoke with such wisdom and acted in violation of human nature, they began to consider among themselves the fact that the tongue of a mere child could never utter such wisdom and such sense. They came to believe that the Holy Spirit had infused her with the words, the same power who worked such wonders in St. Nicholas when he was still in the cradle and inspired him to turn his childlike faculties in the direction of God. (855-75)51

For her parents the key factors are her willingness to die, the wisdom of her arguments, and the fact that her desires run contrary to human nature.52 The decisive evidence is the wisdom and sense of her arguments, and the saintly exemplar is St. Nicholas. Convinced, the parents tell Heinrich of the girl’s resolve and give him their permission. Persuaded by the parents’ support, Heinrich finally agrees to go through with the sacrifice. One last signal resounds in tears and wailing; as many commentators have noted, Heinrich, the parents and the girl all weep for different reasons, but the Meier’s daughter’s motivation is the only one that could in any way be termed selfless: She weeps out of fear that Heinrich will not go through with it.

The peasant girl’s conduct at the doctor’s office in Salerno, where the sacrifice should take place, evokes further parallels with the Virgin Martyrs. Convinced that Heinrich has intimidated the girl into acquiescence, the Master attempts to dissuade her by graphically describing what brutality awaits her. He first will strip her naked, an act of humiliation that in and of itself will ruin any aspirations of marriage. He then will tie her hands and feet, making it impossible for her to resist. And then he will cut into her living body and remove her beating heart. But the sternest test of all will be spiritual. If her resolve wavers for just an instant, the cure will cease to work and all of her suffering will be for naught. The girl’s response betrays verbal aggression reminiscent of St. Agnes and St. Agatha.53 She admits to having second thoughts, but only about the courage of the Master: She taunts him: Is he up to the deed, or is he too much of a coward? She tells him laughingly that she cannot wait, and that she is approaching the sacrifice as though she were going to a dance. As St. Agatha is being stretched on the rack, she says to Quintianus, “These pains are my delight! It’s as if I were hearing some good news, or seeing someone I had long wished to see, or had found a great treasure.”54 Chastened, the Master locks the door.

In a final fearless act, the girl does not wait to be stripped, but rips off her clothes and stands with no shame before the doctor. He then binds her to the table, and whets his knife in preparation for the sacrifice. Martha Easton has advanced the possibility that the act of stripping the martyr creates “the elision of gender” in the spiritual sense. “A naked martyr. . . suggests a rebirth in to a state of grace in which gender is transcended.”55 Nakedness in this context also could signify a kind of baptism, a “stripping away of the cares of the material world and a return to innocence.”56 And this connection to baptism, in turn, would signal the unification of opposites. If the audience had read the maiden’s aggressive act in these terms, then the maiden’s act would signify the acceptance of the virgin martyr’s fate, “to be stripped, baptized in blood and clothed in the glory of heaven.”57

Once the Meier’s daughter is bound and helpless, the moment of truth and transition is at hand. Heinrich, who has been waiting in the other room, wishes to see her one last time. He peeks through a hole in the wall and spies her naked, bound, and helpless. The sight of her inspires Heinrich to turn his life around completely.58 Heinrich’s new kind of goodness involves living in imitation of Job: “One should accept everything that God imposes.”59 When Heinrich stops the sacrifice, the girl’s steadfast defiance and verbal aggression so suggestive of a virgin martyr is transformed by a total reversal of roles, signaled by the narrator’s words, she breaks “every rule of behavior and conduct.” The Meier’s daughter labels her lord a coward and berates him for lacking the courage to do what she was ready to do. She tears her hair and yammers bitterly for death. In a chiastic moment the knight has learned to accept his fate even as the potential martyr refuses to accept hers, dissolving into self-pity and despair.

At this point God intervenes and brings healing to both sufferers.

Then the Diviner of Hearts (cordis speculator), to whom the gate of every single heart is open, recognized her constancy and her suffering. After he had shown them the honor of putting them to such a rigorous test, just as he had the rich man Job, the holy Christ now showed how much he values constancy and compassion for others and delivered them from all of their suffering. He made Heinrich healthy again.60

Noteworthy here is the fact that the Meier’s daughter is mentioned first at this moment of redemption, with her constancy (“triuwe”) and suffering (“not”) cited as the reasons for the imposition of God’s grace. Here, too, we find the most powerful argument in favor of reading Hartmann’s tale as two parallel figures in quest of redemption. When God heals the maiden of her despair, He also heals Heinrich of his leprosy. Thus the despair that had so marred her beauty and the awful disease that so marred Heinrich’s inner transformation vanish through God’s grace. Both are healed, physically and spiritually. Their historically impossible marriage can be read as the worldly expression of their spiritual equality. The question of the Meier’s daughter’s sainthood has been answered. At stake was not a chance for total sacrifice or martyrdom, as the girl had believed, but rather the gift of suffering as a test of goodness and patience. The true exemplar for both Heinrich and the Meier’s daughter turns out to be Job, not Nicholas. The virtue to be tested is not otherworldly goodness but rather the patience of a sufferer who has been plunged into the dark night of the soul.

Conclusion

This intertextual exploration of Hartmann’s tale has unearthed incontrovertible evidence for the existence of a “concept of childhood” in vernacular courtly literature of the twelfth century. The Meier’s daughter’s interactions with the knight Heinrich and the parents’ response to her desire to sacrifice herself would not have made sense to the audience unless measured against a clearly-understood expectations of how children behaved. Even when one factors in the possibility that hagiography, tales of the holy family, or legends supplied the plot material for Hartmann’s story, the following assumptions regarding notions of childhood retain their validity. A stage in life is depicted before which marriage, or in this case, marriage-related sacrifice is possible. Judging from the peasant girl’s interaction with Heinrich and with her family, a “normal” child of wealthy peasants would be expected to work on her parents’ land, obeying them in everything until such a time as when she would be married to a man of equal station, a man whom the parents would choose. She would then live under the authority of this man, submitting to him in everything and risking her life in childbirth every year, with the family’s existence under constant threat from natural catastrophes or changes in the feudal structure.

Into this scenario Hartmann introduces the medieval notion of divine intervention in the form of saintliness. Just as medieval audiences were intrigued by stories of Jesus’ childhood, in which the father Joseph must deal with an omnipotent son, so does Hartmann play with the narrative possibilities of peasant parents confronting their seemingly saintly daughter. Normal children would shun a leper; she spends every possible minute in the leper’s company. Normal peasants do not consort with the nobility; she is Heinrich’s sole companion and source of happiness. The elaborate stages of courtship, meant to transpire between noble knights and ladies in courtly settings of fortress or palace, take place in Hartmann’s tale on a remote clearing, with a peasant girl child playing the role of Heinrich’s bride. In these initial displacements arises the principal riddle that underlies the rest of the story: Will the peasant girl-child develop into a peasant’s wife like her mother or into a virgin martyr? The audience encounters her as a child and follows her fate into adolescence. Just as in the apocryphal tales of the holy family, where we see Jesus the helpful toddler develop into the angry adolescent who instructs the rabbis and chases the moneychangers from the temple, so, too, does the Meier’s daughter have the potential to develop from the devoted handmaiden of a leper into the virgin martyr.

Although he equips the maiden with the compassion of Magdalene, the wisdom and eloquence of Catherine and Nicholas, the defiance and verbal aggression of Agatha, the fervent desire for Christ the bridegroom of Agnes, and the helpless nakedness of Catherine and Margaret, Hartmann transforms the peasant girl’s situation to fit the medieval context. In the place of the pagan suitor stands Heinrich the sinful leper. The absolute dichotomy between noble and peasant replaces that of pagan and Christian. The daunting test of faith contained in the doctor’s cure has replaced the threat of torture and execution. Although martyrdom as defined by the church was no longer officially acknowledged, martyrs in the medieval sense were depicted either as victims of heretics61 or as those who are willing to accept death even if given foreknowledge of it, as is the case of Meinrad.62 Since the heretic motif did not fit his plot, Hartmann chose foreknowledge of death, in this case, in the form of willing sacrifice in order to establish the girl’s potential for martyrdom. When the girl’s helpless nakedness, in the context of virgin martyrdom a sign of transcendence, both of sex and or gender, inspires Heinrich’s inner transformation and stops the sacrifice, this is a final obeisance to the ability of saintliness to enlighten and convert the sinful. And for the Middle Ages this saintliness could reside as easily in the body of a bound eleven-year-old as in the stately bearing of a bishop.

Even as w e accept the paradigm shift in our understanding of medieval childhood, as it has been documented in this volume, the concept of childhood that emerges from Hartmann’s tale as read through hagiography still differs in significant ways from that of modernity. The potential for divine intervention in every dimension of medieval life meant that an audience’s grasp of binaries such as parent/child, noble/peasant, wise/foolish had to be much more fluid and dynamic. Whereas all facets of medieval life were organized into categories according to strict hierarchies, the possibility for reversal and transformation through divine power could never be completely eliminated. In such contexts, categories that define childhood and childlike behavior are transformed from static taxonomies into dynamic processes that required investigation and demanded miraculous confirmation. The basis for such a process, as depicted in Der arme Heinrich, rests in Hartmann’s clear depiction of both the physical and the affective dimensions of childhood in a context that reflects, at least in some sense, the economic and social conditions of his time.

Endnotes

- See Nicholas Orme, Medieval Children (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), 5. See also Shulamith Shahar, Childhood in the Middle Ages (London ; New York: Routledge, 1990); Barbara Hanawalt, Growing Up in Medieval London: the Experience of Childhood in History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993); James A. Schultz, The Knowledge of Childhood in the German Middle Ages, 1100-1350. Middle Ages Series (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995); Ronald C. Finucane, The Rescue of the Innocents: Endangered Children in Medieval Miracles (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997); and Daniele Alexandre-Bidonand Didier Lett, Children in the Middle Ages: Fifth-Fifteenth Centuries, trans. Jody Gladdings (Notre Dame, IN.: University of Notre Dame Press, 1999).

- I use this term as defined by the medievalist Hans Robert Jauss, not as adapted by post-colonial theorists. See Hans Robert Jauss, Alterität und Modernität der mittelalterlichen Literatur: Gesammelte Aufsätze 1956-3976 (Munich: W. Fink, 1977), 9-47. James Schultz makes this same point a bit more polemically in his review of Orme’s book: “He is unwilling to acknowledge that there are both similarities and differences between medieval and modem childhood, that the similarities and differences fit together in an historically specific idea of childhood, and that, as part of such an historical construct, even the similarities become differences, because their different context gives them meanings different from the ones they have today.” See Medievalia et Humanistica 30 (2004): 158-59; here 159.

- See Bernard McGinn, Visions of the End: Apocalyptic Traditions in the Middle Ages. Records of Civilization, Sources and Studies, 96 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1979); Richard Kenneth Emmeison, Antichrist in the Middle Ages: a Study of Medieval Apocalypticism, Art, and Literature (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1981); and Richard Kenneth Emmerson and Ronald B. Herzman, The Apocalyptic Imagination in Medieval Literature. Middle Ages Series (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992).

- Richard Kieckhefer and George Doherty Bond, Sainthood: its Manifestations in World Religions (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 3.

- Ibid., 11-13.

- Ibid., 4-5.

- Many of these issues have been debated by historians in the context of New Historicism. See Catherine Gallagher and Stephen Greenblatt, Practicing New Historicism (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2000) for a update on the details of this debate.

- For useful studies of the depiction of saintly childhood, see Donald Weinstein and Rudolph M. Bell, Saints & Society: the Two Worlds of Western Christendom, 1000-1700 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1982); Michael Goodich, Vita perfecta: the Ideal of Sainthood in the Thirteenth Century. Monographien zur Geschichte des Mittelalters, 25 (Stuttgart: A. Hiersemann, 1982); and the anthologies by Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski and Timea Klara Szell, Images of Sainthood in Medieval Europe (Ithaca, Ν. Y.: Cornell University Press, 1991); and Kieckhefer and Bond Sainthood.

- Goodich, Vita perfecta, 82.

- Ibid.

- “Motive und Bildkomplexe, Wunder, Visionen und besondere Gnadenauszeichnungen – sei[en] bewusst oder unbewusst aus früheren literarischen Quellen übernommen.” This skeptical perspective, as elucidated in Siegfried Ringler, Viten- und Offenbarungsliteratur in Frauenklösterndes Mittelalters: Quellen und Studien. Münchener Texte und Untersuchungen zur deutschen Literatur des Mittelalters, 72 (Munich: Artemis Verlag, 1980), 13, provoked a polemical response from the historian Peter Dinzelbacher. The resulting debate illuminated many key issues surrounding the value of medieval didactic sources for historians. See Peter Dinzelbacher, “Zur Interpretation erlebnis mystischer Texte des Mitlelalters,” Zeitschrift ßrdeutsches Altertum und deutsche Literatur 117 (1984): 1-23. Frank Tobin offers an insightful summary and analysis of the debate in Frank J. Tobin, Mechthild von Magdeburg: a Medieval Mystic in Modern Eyes (Columbia, S.C.: Camden House, 1995), 110-25.

- Goodich, Vita perfecta, 85.

- “A sua pueritia cor gerens, senile satagabat; levitas vitando, bonos assuescere mores et insolentios fugere juveniles” Acta sanctorum (October 17, VIH): 224, cited in Ibid., 88.

- http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/vita-antony.html (last accessed on March 14, 2005).

- Goodich, Vita perfecta, 89.

- “Des ersten Tages, da man Sanct Nicolaus das Kindlein baden sollte, da stund es aufrecht in dem Becken, und wollte auch am Mittwoch und Freitag nicht mehr denn einmal saugen seiner Mutter Brust. Als das Kind zu Jahren kam, schied es sich von den Freuden der anderen Jünglinge und suchte die Kirchen mit Andacht; und was er da verstand von der heiligen Schrift, das behielt er mit Ernst in seinem Sinne. Als sein Vater und seine Mutter tot waren, begann er zu betrachten, wie er den großen Reichtum verzehre in Gottes Lob und nicht zu der Ehre der Menschen.

- “In der volkssprachlichen wie der lateinischen religiösen Dichtung des 12. und 13. Jahrhunderts sind apokryphe Ereignisse aus der Kindheit Jesu, besonders die Wundertaten während der Flucht, beliebt.” See Susan Marti, Malen, Schreiben und Beten: die spätmittelalterliche Handschriftenproduktion im Doppelkloster Engelberg. Zürcher Schriften zur Kunst-, Architektur- und Kulturgeschichte, 3 (Zürich: Zip, 2002), 207-10; here 208.

- Weinstein and Bell, Saints and Society, 45.

- Ibid., 46.

- Ibid.

- Since most Middle High German collections date back only to the early fifteenth century, I shall use the most popular and widely disseminated collection of hagiography of the High Middle Ages, Jacobus de Voragine’s Golden Legend. All quotations from the Golden Legend are taken from Jacobus and William Granger Ryan, The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints. 2 vols. (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1993).

- This division also favored particular themes, that of childhood neglect and deprivation for the first phase and that of challenges to parental authority in matters of vocation in the second. See Goodich, Vita perfecta, 82 and 100.

- Hartmann is famous as the first adaptor of Arthurian romance in Middle High German. His reworkings of Chretien de Troye’s Yvain and Erec have become classics of the German Middle Ages. He also wrote Minnesang, a discourse on courtly love, and a religious epic Gregorius. For what little we know of Hartmann’s life, see “Hartmann von Aue” Kurt Ruhe et al., ed., Die deutsche Literatur des Mittelalters: Verfasserlexikon, 2., völlig neubearb. Aufl. (Berlin and New York: W. de Gruyter, 1977), and Andre Vauchez, R. B. Dobson, and Michael Lapidge, Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages (Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 2000).

- For the voluminous secondary literature on Hartmann’s Der arme Heinrich, see Christoph Cormeau and Wilhelm Stürmer, Hartmann von Aue: Epoche, Werk, Wirkung. Arbeitsbücher zur Literaturgeschichte (Munich: Beck, 1985), 142-59. Will Hasty’s summary of scholarship on Der arme Heinrich is also useful. See Will Hasty, Adventures in Interpretation: the Works of Hartman von Aue and Their Critical Reception. Literary Criticism in Perspective (Columbia, SC: Camden House, 1996), 68-78. See also Petra Hörner, Hartmann von Aue: mit einer Bibliographie 1976-1997. Information und Interpretation, 8 (Frankfurt am Main and; New York: P. Lang, 1998).

- In one sense, I am returning to the interpretations of the fifties when commentators depicted the peasant daughter as a saintly presence who guides Heinrich on the path to salvation. For just one example, see Bert Nagel, Der arme Heinrich Hartmanns von Aue: eine Interpretation. Handbücherei der Deutschkunde, 6 (Tübingen: M. Niemeyer, 1952). Reading Hartmann’s tale through the perspective of hagiography makes a straightforward interpretation like Nagel’s untenable. Saintliness can only be examined as an open question.

- Saul Nathaniel Brody, The Disease of the Soul: Leprosy in Medieval Literature (Ithaca N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1974), 147-97, surveys the literary depiction of leprosy with specific reference to Hartmann (148-58).

- For a survey of earlier scholarly opinion on the issue of Heinrich’s guilt, see “Heinrichs Sturz” in Barbara Könnecker, Hartmann von Aue: Der arme Heiricft (Frankfurt: Diesterweg, 1987), 61-66. See also Hasty, Adventures, 72-73 and Ronald Finch, “Guilt and Innocence in Hartmann’s Der arme Heinrich,” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 73 (1972): 642-52.

- nü ist genuoc unmügelich, daz ir deheiniu durch mich gerne Ilde den töt. des muoz ich schäntliche not tragen unz an min ende (453-57). All quotations from Hartmann’s text are from Hartmann von Aue, Der arme Heinrich, 17., durchgesehene Auflage. Altdeutsche Textbibliothek, 3 (Tübingen: M. Niemeyer, 2001). For a reliable translation of Hartmann’s tale, see Hartmann von Aue, Arthurian Romances, Tales, and Lyric Poetry: the Complete Works of Hartmann von Aue, trans. Frank J. Tobin, Kim Vivian, and Richard H. Lawson (University Park, PA.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2001). Unless otherwise indicated, however, all English translations of Hartmann in this article are my own.

- Hartmann uses the terms “frier buman” (269) and “meier” (295), which Lexer defines as “peasant,” “ploughman,” or “tenant farmer”. See Matthias Lexer, Mittelhochdeutsches Handwörterbuch, 3 vols. (1872-1878; Stuttgart: S. Hirzel, 1992), here Vol. 1,381 and 2074-75. A “meier” was a kind of overseer who administered the lands in his lord’s name and settled minor legal disputes. This Meier’s wealth and good fortune are attributed to the just rule and protection offered by Heinrich (269-84).

- Two recent interpretations shift the interpretative focus from the parallel protagonists who learned from each other’s fates, a view championed by Cormeau, to the tale of Heinrich’s fate alone. David Duckworth traces Heinrich’s inner evolution from goodness to true charity in light of medieval theological treatises on love. See David Duckworth, “Heinrich and the Power of Love in Hartmann’s Poem,” MediaevistikU (2001): 31-82. This represents a modification of some of the views previously advanced in David Duckworth, The Leper and the Maiden in Hartmann’s Der arme Heinrich. Göppinger Arbeiten zur Germanistik, 627 (Göppingen: Kümmerle, 1996). Albrecht Classen proposes that we read the peasant’s daughter allegorically, as part of Heinrich’s inner landscape. See Albrecht Classen, “Herz und Seele in Hartmanns von Aue ‘Der arme Heinrich.’ Der mittelalterliche Dichter als Psychologe?,” Mediaez’istik 14 (2001): 7-30.

- Cormeau notes: “Der Aussatz ist im Mittelalter eine tabuisierte Krankheit; ihn als Geißel und Strafe Gottes anzusehen, lehrt schon das Alte Testament Diese archaische Auffassung mischt sich mit einem bildhaft allegorischen topos der mittelalterlichen Predigt: die Sünde als Aussatz der Seele.” See Cormeau and Stürmer, Epoche, 146. See also Brody, Leprosy, 60-106.

- si hete gar ir gemüete mit reiner kindes güete an ir herren gewant, daz man si zallen ziten vant under sinem fuoze. mit süezer unmuoze wonte si ir herren bi. dar zuo liebet er ouch s! (321-25).

- Among the vernacular literary genres in which encounters do occur between knights and young maidens, the sexual play and license of the pastourella may be ruled out immediately. And although there is a real resonance with the playful juxtaposition of courtly love, humor, and childlike innocence that so dominates the Obilot episode (including the gift ο fa ring) in Wolfram’s Parzival, social class plays no role; Gawan and Obilot are both of the nobility. I am in no way presuming anachronistic influence here. But Hartmann could have been familiar with similar tales within the cycle of Gawan episodes in Arthurian literature.

- Jacobus and Ryan,77ie Golden Legend, 101-04; here 102.

- She is one of many “schoeniu kint” (beautiful children, 299), but her ability to “rehte güetlichen gebären” (to conduct herself with proper bearing, 304-05) distinguishes her from the others. She attends to him “mit ir güetlichen pflege” (with good-hearted service, 310). She is “sin kurzwile gar” (even a means of innocent pleasure, 320), both for her “genaeme” (pleasant demeanor) and for the “rainer kindes güete” (pure goodness of a child, 322) with which she devotes herself to Heinrich.

- See “Beata Peccatrix” in Susan Haskins, Mary Magdalen: Myth and Metaphor (London: HarperCollins, 1993), 131-88. Especially useful for the reception of Mary Magdalene in the German Middle Ages is Madeleine Boxler,””ich bin ein predigerin und appostlorin”: die deutschen Maria Magdalena-Legenden des Mittelalters (1300-1550): Untersuchungen und Texte. Deutsche Literatur von den Anfängen bis 1700, 22 (Bern and New York: Lang, 1996).

- “er dühte sie viel reine, swie starke ir daz geriete diu kindische miete, iedoch geliebete irz aller meist von gotes gebe ein süezer geist” (344-48).

- “Wan ez hete diu vil süeze ir lieben herren vüeze stände in ir schozen. man möhte wol genözen ir kintlich gemüete hin zuo der engel giiete” (461-66).

- “Si bereite aber ein bat mit weinenden ougen: wan si truoc also tougen nähen in ir gemüete die aller meiste güete, die ich von kinde ie vemam. Welch kint getete och ie alsam” (518-23)?

- “Wanswenneer hie geringet und üf sin alter bringet den lip mit micheler not, sö muoz er liden doch den tot” (601-04).

- “unser leben und unser jugent ist ein nebel und ein stoup” (722-23). “wirt er mir liep, daz ist ein not:

- wirt er mir leit, daz ist der tot. Sö hän ich iemer leit und bin mit ganzer arbeit gescheiden von gemache mit meniger hande sache diu den wiben wirret und si an vreuden irret” (765-72).

- “sö lätz an iuwern hulden stän daz ich ouch diu beide von dem tiuvel scheide und mich gote müeze geben, ja ist dirre werlte leben niuwan der sele Verlust” (684-89).

- “Ez ist mir komen üf daz zil, des ich got iemer loben wil, daz ich den jungen lip mac geben umbe daz ewige leben” (606-10).

- See Jacobus and Ryan, The Golden Legend, Vol. 2, 334-41; here 336. Although Catherine was “well educated in the liberal disciplines” (335), nothing in her training should have enabled her to best the wisest philosophers of the empire. Hence the power relationship “young girl-philosopher” corresponds to Hartmann’s “young girl -parent.”

- Robert Mills offers an interesting reading of many of the motifs under discussion here in Robert Mills, “Can the Virgin Martyr Speak?,” Medieval virginities, ed. Ruth Evans, Sarah Salih, and Anke Bernau, Religion & Culture in the Middle Ages (Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 2003), 187-215; here 189-95. See also Alexander Joseph Denomy, The Old French Lives of Saint Agnes and Other Vernacular Versions of the Middle Ages. Harvard Studies in Romance Languages, XIII (Cambridge,: Harvard University Press, 1938).

- Jacobus and Ryan, The Golden Legend, 102.

- Ibid.: ‘”Is there anyone whose ancestry ismore exalted, whose powers are more invincible, whose aspect is more beautiful, whose love more delightful, who is richer in every grace?’ Then she enumerated five benefits that her spouse had conferred on her and confers on all his other spouses: he gives them a ring as an earnest of his fidelity, he clothes and adorns them with a multitude of virtues, he signs them with the blood of his passion and death, he binds them to himself with the bond of his love, and, and endows them with the treasures of eternal glory. ‘He has placed a wedding ring on my right hand,’ she said, ‘and a necklace of precious stones around my neck, gowned me with a robe woven with gold and jewels, placed a mark on my forehead to keep me from taking any lover but himself, and his blood has tinted my cheeks. Already his chaste embraces hold me close, he has united his body to mine, and he has shown me incomparable treasures, and promised to give them to me if I remain true to him.'”

- “im gät sin phluoc harte wol, sin hof ist alles rates vol, da enstirbet ros noch daz rint, da enmüent diu weinenden kint, da enist ze heiz noch ze kalt, da enwirt von jären nieman alt (der alte wirt junger), da enist deheiner slahte leit, da ist ganziu vreude äne arbeit” (779-88).

- Despite all of the references to the potential of sainthood just noted, Hartmann is careful to include some signs that would support the audience’s doubt. The dynamic flow of the peasant maiden’s rhetoric begins with her determination to sacrifice herself for Heinrich and, given his healing, for her parents. Yet it makes her fate on earth into its chief concern until the bridegroom-soliloquy stresses the depravity and spiritual dangers posed by life more than the glory of the Bridegroom, as is the case in Agnes’ vita. The girl’s concluding words even propose alimit to selflessness, something no saint would ever countenance: “Whoever provides so much happiness to another such that he himself becomes unhappy, and whoever elevates another such that he humiliates himself, he is wearing too much the yoke of fidelity” / ” swer den andern vreuwet so, daz er selbe wirt unfrö, und swer den andern kroenet und sich selben hoenet, der triuwen si joch ze vil” (823-27).

- “Do si daz kint sähen zem töde also gähen, und ez so wislichen sprach unde menschlich reht zerbrach, si begunden ahten under in, daz die wisheit und den sin niemer erzeigen künde dehein zunge in kindes munde, si jähen, daz der heilic geist der rede waere ir volleist, der ouch sant Niklauses pflac, dö er in der wagen lac, und in die wisheit lerte, dazer ze gote kerte sine kintliche güete” (855-75).

- Lexer, Handwörterbuch, 377. Lexer defines “reht” as “die Gesamtheit der rechtlichen Verhältnisse jemands, was man zu fordern und zu leisten hat.” Examples: “kristenlichez recht” is the sacrament, “geistliches reht” is investiture, “menschlichezreht begehen” is a synoym for suicide, and “weiblihes recht” is menstruation. The word field seems to indicate that the qualities the parents have in mind are god-given as a part of nature.

- Gerhard Eis, “Salernitarischesund Unsalernitarisches im ‘Armen Heinrich ‘des Hartmannvon Aue,” Forschungen und Fortschritte 31 (1957): 77-81, argues against earlier interpretations that saw precise parallels between the peasant daughter’s behavior and that of the martyrs. But enough of a suggestion is there to leave the question open to the audience’s speculation.

- Jacobus and Ryan, The Golden Legend, 154-57; here 155. See also the words of St. Agnes, “I will not sacrifice to your gods, and no one can sully my virtue because I have with me a guardian of my body, an angel of the Lord” (Jacobus and Ryan,77 ie Golden Legend, 101-04; here 103.

- Martha Easton, “Pain, torture and death in the Huntington Library Legenda aurea,” Gender and Holiness Men, Women, and Saints in Late Medieval Europe, ed. Samantha Riches and Sarah Salih (London and New York: Routledge, 2002), 49-64; here 53.

- Ibid., 53.

- Ibid.

- Every commentator who has written on this story has attempted to supply the missing motives here for Heinrich’s change of heart. For helpful discussions of the dualistic and gradualistic positions, see Cormeau and Störmer, Epoche, 156-57; Hasty, Adventures, 75-77; Eva-Maria Carne, Die Frauengestalten bei Hartmann von Aue: Ihre Bedeutung im Aufbau und Gehalt der Epen. Marburger Beiträge zur Germanistik, 31 (Marburg: N. G. Elwert, 1970), 53-55; and most recently, Classen, “Herz und Seele,” 10-12.

- “swaz dir got hat beschert, daz lä allez geschehen” (1254-55).

- “dö erkande ir triuwe und ir not cordis speculator, vor dem deheines herzen tor vürnames niht beslozzen ist. slt er durch sinen süezen list an in beiden des geruochte, daz er si versuochte reht also volleclichen sam Jöben den riehen, do erzeicte der heilic Krist, wie liep im triuwe und bärmde ist, und schiet si dö beide von allem ir leide und machete in da zestund reine unde wol gesunt” (1356-70).

- Goodich, Vita perfecta, 190-93.

- Klaus Klein, “Meinrad,” Die deutsche Literatur des Mittelalters: Verfasserlexikon, ed. Kurt Ruh et al. 2., völlig neubearb. Aufl. (Berlin and New York: W. de Gruyter, 1987), Vol. 6, 319-22.

Contribution (229-246) from Childhood in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, edited by Albrecht Classen (Walter de Gruyter, 07.18.2005), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported license.