The dividing line did not run between individual gods, but between human beings and gods.

By Dr. Michael Lipka

Professor of Religious Studies

University of Patras

Since they were conceptualized as human beings, Roman gods had a place in this world, in which they moved freely. This conclusion is unavoidable, if we consider that all Roman gods could be invoked, and that invocation implied spatial proximity to the invocator.1 Apart from this, at least the major gods were conceptualized as connected to specific locations, normally marked as such by an altar, a temple, or in some other way. These locations I will call ‘spatial foci’. They are mostly represented by archaeological remains. However, by relying on archaeology, we unduly overemphasize the spatiality of major official divine concepts, which were more likely than private cults to be permanently conceptualized by specifically marked space.

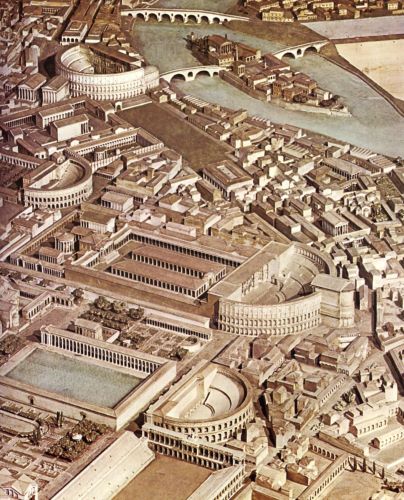

The sacred landscape of Rome was complex, time-bound and notoriously anachronistic. It was complex because its parameters were not absolute and necessarily recognizable as such. Rather, it was intrinsically relative and existent only within the full semiotic system of the topography of the city. Furthermore, it was time-bound, because the city itself developed rapidly, especially during the peak of urbanization from ca. 200 B.C.–200 A.D. It was notoriously anachronistic because the semiotic system underlying it was highly conservative and did not keep pace with the actual urban development (for instance, the pomerium was still remembered, when it had long become obsolete in the imperial period in terms of urban development; and the festival of the Septimontium was still celebrated separately by the communities that had long since merged into the city of Rome).

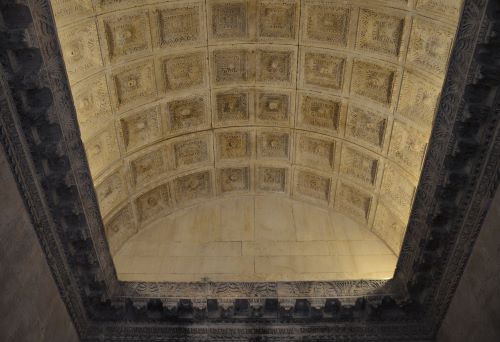

It is not always easy to pin down the relation to space of divine concepts in so inconsistent and fluid a semiotic environment. The allocation of specific space to a divine concept was determined by mutually competing factors such as the status and motives of the founder of the cult, the availability of and historical connection with a specific place, the money to be invested, the function of the god, general religious restrictions imposed by parameters such as the pomerium and other regulations of the augural law, etc. This daunting plethora of factors makes it easy to overlook the fact that one element is common to public cults (and is often adopted in the private sphere too): the architectural language of space. For it is scarcely self-evident that the large variety of divine concepts in the city was marked by more or less the same architectural forms, in one way or another already present in the most important spatial focus of pagan divine concepts ever created in Rome, i.e. the temple of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitol. One may argue that in the case of altars, the margin for variation was narrow due to the simplicity of the architectural type. However, this explanation cannot hold true of the temple, which was anything but a simple structure. Characterized by a frontal colonnade on a podium to be reached over a stairway and supporting a triangular pediment, which was normally adorned with some sort of sculpture or other decoration, its homogeneous appearance was not intended to express the differences among the various divine concepts worshipped in it, but to set it off from profane architecture.2 In terms of architectural forms, then, all public cults were essentially equal and clearly marked off from the various building-types of human beings. Given this basic dichotomy, the actual architectural forms in each category could differ, i.e. each architectural detail could be modified or substituted for another, as long as the remaining details sufficed to provide the relevant spatial concept of either profane or divine architecture. The fact that, architecturally speaking, the dividing line did not run between individual gods, but between human beings and gods, explains the public outcry when Cae-sar erected a pediment, characteristic of divine spatial concepts, over the façade of his private residence.3 By doing so, he in fact challenged this dichotomy, in order to underpin his super-human claims.

The more important a divine concept was felt to be, the more firmly it was grounded in the sacred landscape of the city. Gods that represented only a slight or no specific local affiliation were notoriously ephemeral and specialized. Most striking is the group of ‘functional’ gods, who, as their name indicates, were predominantly conceptualized on the basis of function. They rarely received official recognition in urban topography, i.e. a spatial focus, or in the calendar, i.e. a temporal focus. Nor were they characterized by particular rituals or a specific iconography. Another case in point is a number of antiquated deities, kept alive by pontifical tradition, though virtually forgotten by the people due to the fact that they were no longer present in urban topography. One may refer to the goddess Fur(r)ina: Varro mentions the goddess and her priest in connection with the festival of the Fur(r)inalia (July 25). But he also acknowledged that, in his day, the name of the deity was hardly known to anyone.4 A further case is that of Falacer, of whom virtually nothing is known apart from the existence of his flamen.5

It is of specific relevance to the formation of ‘gods’ by spatial foci to note that during the Republican period, augurally constituted space, such as a cella of a public temple, could typically be dedicated to just one deity at a time.6 The exact process of constituting augural space is thereby somewhat obscure, because the knowledge of the augural discipline was jealously guarded by the augurs themselves and passed on only by oral transmission.7

In the pagan world, the cult statue of a specific god (meaning: the iconographic focus of a specific cult) was directly linked to the spatial focus of the god. In other words, no cult statue could function as such independently of or outside the spatial context in which it was placed. Sylvia Estienne pointed out after an investigation of such potentially ‘isolated’ cult statues that “it is not so much the statue that makes the cult place, but rather the place itself that marks the statue as a cult object.”8 The two concepts of place and statue are linked up to form the new concept of ‘cult place’, with ‘place’ being the dominating factor. Its dominance is due to its lack of ambiguity: divine space, normally marked unequivocally by some sort of architecture, could scarcely be taken for something else, whereas a statue could always be seen as mere decoration.

The principle of spatiality is widely applied elsewhere too. The proximity of a statue to the spatial focus of a cult was an indicator of the degree to which it was intended to serve as an iconographic focus of the cult. For instance, Caesar placed an image of Cleopatra next to the cult image of Venus Genetrix, because he wanted to assimilate his mistress to the goddess.9 In the same vein he placed a statue of himself in the temple of Quirinus (and that meant no doubt next to the cult image), adding the inscription “to the invincible god”.10 On the other hand, when Agrippa intended to place a statue of Augustus in the newly erected Pantheon in 25 B.C., the emperor rejected the honour. Agrippa, in turn, set up a statue of Caesar instead, while statues of the emperor and himself were erected in the anteroom of the building.11 The message was plain: while Caesar had already gained divinity and hence was entitled to associate with the gods directly in the “holiest”, innermost part of the sanctuary, Augustus and Agrippa were still human and therefore to be located in the periphery of the “holy” center.12 Meanwhile, low-profile Tiberius accepted the erection of his statues in temples on the condition that they were placed not among the cult images of the gods, but in the temple decoration (inter ornamenta aedium).13 Fine examples of the deliberate juxtaposition of representations of historical persons and spatial foci of a god are the two altars of Mercy and Friendship, flanked by statues of Tiberius and Seianus, following a senatorial decision in 28 A.D.14 According to contemporary sources, it was a mark of restraint that only two bronze statues of Trajan (in contrast to the large number of Domitian’s effigies) were erected in the Capitoline area, and more importantly, not in the cella, but in the vestibule.15 The underlying principle of spatiality is ominipresent: the closer to the divine in spatial terms, the more divine in conceptual terms.

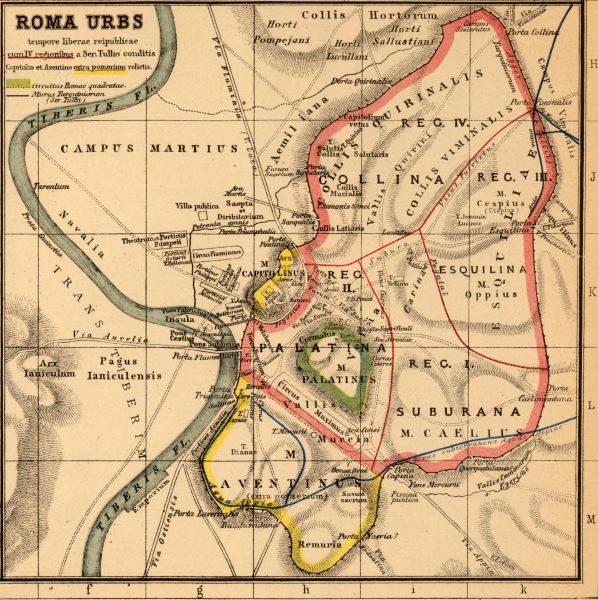

Inaugural thinking, the border of the city was not the city wall (which was built according to strategic considerations) but rather an augurally defined strip of land which surrounded the city and was referred to as the pomerium. It formed the limit of the augural ‘map’ (auspicia urbana). Essentially, this line did not differ from the border line of any inaugurated place, which means that its exact course had to be clearly visible: in other words, no buildings were supposed to be built on or directly next to it.16 The earliest pomerium included the Palatine and not much more.17 According to tradition, Titus Tatius later added the Forum and the Capitol, while Servius Tullius included the Quirinal, Viminal and Esquiline.18 Sources report further modifications from Sulla’s time onwards.19 Surprisingly, the Aventine was excluded from the pomerium, at least until the first century A.D., when it had in any case lost all religious significance.20

The long-standing view that foreign cults, when introduced to Rome, were given a place outside the pomerium during the Republic has been challenged by Ziolkowski, who has argued that the prime parameter in choosing the location for a temple was the availability of suitable space regardless of the pomerium line. Ziolkowski showed that the traditional ‘Roman’ gods occupied the more central areas in urban topography from prehistoric times, while the lack of space resulting from the increasing urbanization led to the accommodation of new gods in the periphery of the existing settlements.21 On occasion, the actual sphere of competences of a specific deity may have determined the choice of location, as Vitruvius claimed.22 For instance, the extra-pomerial location of healing gods, such as Apollo in the Campus Martius and Aesculapius on the Island in the Tiber, could be interpreted as an attempt to avert from the old city diseases that had been associated with these deities. Furthermore, the two healing gods were situated not only outside the pomerium, but virtually next to each other, with the temple of Aesculapius separated from the temple of Apollo by the Tiber.23 But again, in his stress on the importance of divine functions concerning the distribution of sanctuaries Vitruvius is at least partly contradicted by Roman evidence.24

Interestingly, Vitruvius regards the city wall—not the pomerium—as the basic topographical demarcation line.25 His claim is supported by the fact that cults of some of the oldest and most prominent Roman gods such as Iuppiter Elicius, Ceres, Diana and Iuno Regina26 were situated outside the pomerium, that is to say, on or next to the Aventine hill, though inside the city walls (which included the hill as early as the archaic period).27 Again, one should not overstress the importance of the city wall in these contexts, but it would seem only natural that cults essential to the religious functioning and well-being of the city (Iuppiter Elicius, Ceres, Diana) should be situated within the walls, if only for reasons of control and protection.

The most important god of Roman public life over the centuries was undoubtedly Iuppiter. When the Romans conceptualized this divine form, they conceptualized it as locally bound to a number of places in the city. The most important spatial focus of the cult of the god was the temple area on the Capitol. It was not only the size of the area, but also the architecture of the temple itself and the rich offerings displayed around it that rendered its spatial position paramount, not only among all Jovian temples, but in general among all sacred areas in the city. Besides this, its geographical position—set high above the Forum Romanum to the east and the commercial markets (Forum Holitorium and Forum Boarium) to the south—highlights the spatial focus of Jovian worship in comparison to the spatial foci of other gods. But Jovian worship did not focus only on the sanctuary of the Capitoline triad, but also on the entire Capitoline hill. It is not by chance that we find an impressive number of other Jovian sanctuaries in the area.28 They were placed as close as possible to their source of power.

While the reason for the location of the oldest form of Iuppiter on the Capitoline, that of Iuppiter Feretrius, is unknown (though well in line with the general tendency to worship Iuppiter on hill tops), it is likely that the location of the temple dedicated to Iuppiter, Iuno and Minerva was a secondary choice. The triad was also worshipped on the Quirinal (Capitolium Vetus).29 Since the appearance of the same triad at two places cannot be coincidence, one has to conclude that it was deliberately transferred, or better still (since the Capitolium Vetus still appears in the Regional Catalogues of the fourth century A.D.), duplicated on the Capitol or vice versa on the Quirinal. If the Quirinal triad was the earlier one (but there is so far no way to prove this), the reason for this duplication may have been a deliberate act of political instrumentalization of the Quirinal triad. While the various autonomous settlements in the area were gradually synoecizing, a political and economical centre emerged around the Capitoline area in the seventh century. Naturally, the god that came to embody the idea of this centralized urban structure had to be located at its very center. In brief, if my assumption of the priority of the Quirinal triad is correct, the location of the Capitoline triad was dictated by, and resulted from, political conditions.

Indeed, piety played at most a minor role in duplicating a specific cult outside its original spatial setting. We need only refer to the two known spatial foci of the cult of Quirinus. The no doubt older one was situated on his hill, the Quirinal, while the other, the ‘doublet’, was to be found in the political centre, i.e. in the Forum.30 The same may be said of the cult of Isis. Epigraphical evidence suggests that Isis was linked to a specific place on the Capitoline from the middle of the first century B.C. at the latest (see below). This Capitoline cult appears to have been ‘duplicated’ in the so-called Iseum Metellinum.31 It is tempting to follow Coarelli in suggesting that this Iseum belonged to the first half of the first century B.C. (rather than to the imperial period, as commonly suggested) and to regard Q. Caecilius Metellus Pius (cos. 80 B.C., died 64/63 B.C.) as its founder. It was erected, according to Coarelli, in order to celebrate the military achievements of Metellus’ father, Metellus Numidicus, in the war against Jugurtha.32 Even if this reconstruction of events is hypothetical, the very characterization of the Iseum as Metellinum suggests a political reason, i.e. the (self-) promotion of the family of the Metelli, for its erection. In the same vein, we may point to the countless doublets of the Capitoline temple of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus in the market places of Roman colonies at later times. Their location in the political centre of their cities was clearly a means of political propaganda: were it otherwise, we would wonder why such Capitolia were only very exceptionally situated away from the political centres of the relevant cities.33

Space was also a constituent concept of ‘unofficial’ gods and their cults, such as that of Bacchus at the beginning of the second century B.C. Here, it is the Aventine hill that was particularly connected with the cult of the god, perhaps originally as an unofficial offshoot of the cult of Liber, who was worshipped there as part of the Aventine triad from the beginning of the fifth century B.C. at the latest. It was in the vicinity of the Aventine, i.e. outside the pomerium, that the grove of Stimula (= Semele), with a shrine (sacrarium) dedicated to the goddess or her divine son (or possibly both), was located.34 It is telling that contentious divine concepts such as that of Semele could be derived from official gods such as the Aventine triad by the principle of spatiality, i.e. by positioning their cultural centre in close local proximity. In a sense, the cult of Semele was just the ‘other’, ‘dark’ side of the Aventine triad, which was located virtually next door to her.

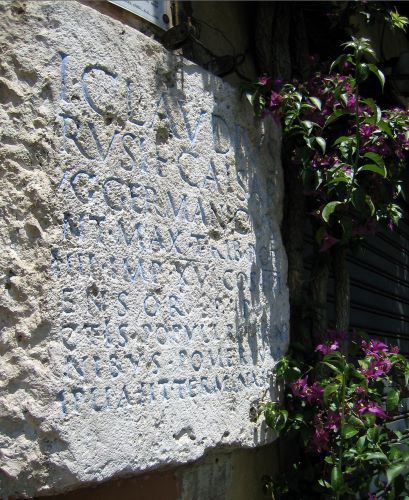

In terms of spatial setting, recently imported deities in Rome, with the exception of the Christian god, followed the same pattern as the traditional gods. Most of all, they were linked to specially established areas. Apparently, the first spatial focus of the cult of the Egyptian Isis was situated on the Capitoline. It is of little significance whether shrines or altars were erected there35 or, for that matter, a temple in her name.36 Epigraphic evidence dating from the mid-first century B.C. at the latest attests to the existence of priests of Isis Capitolina. Given that this form of Isis (with the epithet ‘Capitolina’) is locally bound, it is obvious that there was a spatial focus of the cult of the goddess on the Capitol with a priest conducting the cult.37 Considering the repeated expulsions of the goddess from inside the pomerium,38 and, during the first century B.C., explicitly from the Capitol region, it is also clear that the cult began on the Capitol as a private foundation, i.e. it was situated on private property. This dovetails with the fact that in the middle of the first century B.C., some areas of the Capitol were in private hands.39 Considering the private nature of the cult, one should note that the location of this precinct—adjacent to the highest state god and situated above the old city centre—is both a rare and an expensive privilege. This suggests that some of its adherents were of financial ease. Perhaps in the wake of repeated expulsions of Isis from the city area, the goddess was eventually relegated to a new precinct in the Campus Martius during the final years of the first century B.C. (Isis Campensis).40

If we turn to imperial worship, a slightly different picture emerges. On the one hand, the appearance of the emperor in various spatial settings was modelled on that of the traditional gods; while on the other, due to a certain reluctance to display the emperor’s divinity in the capital, these places functioned only indirectly as spatial foci. The most important indication of such ‘indirect’ focalization is the absence of a temple. This situation changed at the moment of the emperor’s death, when as a rule a temple was erected in his name.

‘Indirect’ spatial focalization can be illustrated by the worship of Augustus at the crossroads: shortly before 7 B.C., Augustus reorganized the administrative map of the metropolis by dividing it into 4 regions (regiones) and 265 residential districts (vici). In each district the emperor established one or more shrines (compita) at which the Lares of the imperial house, that is to say the Lares Augusti, were worshipped (the worship of his own genius is likely, but less certain). In doing so, Augustus spectacularly modified the age-old cult of the Lares Compitales who were traditionally worshipped at the crossroads and had their own festival, the Compitalia or Laralia. Given the numerous districts and the possibility that more than a single shrine was erected in each, there can be little doubt that the Augustan Lares were, from now on, present in this new—divine—context throughout Rome.41 Nor was it by chance that the emperor himself paid for the expenses of the new cult statues and possibly the altars.42

While Augustus and his successors remained fond of such assimilation, they were disinclined towards direct identification with the divine in Rome during their own lifetime. In a passage already mentioned, Augustus rejected the erection of his statue in the main room of the Pantheon and its name Augusteum. Instead, his effigy was set up in the ante-chamber of the building (while a statue of Caesar was placed in the main room).43 In a similar vein, Augustus dedicated a temple to Apollo next to his Palatine residence in 28 B.C. This location automatically led to a conceptual assimilation of the princeps to the very god he had chosen as his tutelary deity. No wonder then that the temple was to operate as a focal point of Augustan propaganda, both culturally (with a library of Greek and Roman authors attached to it), politically (with its central role during the Secular Games in 17 B.C. and senatorial meetings convened in it) and religiously (with the Sibylline books stored in it).44 In spatial terms, the temple was connected to Augustus’ residence via private corridors, so that the princeps could approach the god without stepping out in the open.45 In other words, “the princeps not only lived next to, but close to and together with his tutelary deity.”46 Spatial proximity here as elsewhere suggested conceptual similarity, fully in line with the principle of spatiality. Even more importantly, the motivation of this assimilation to the divine is apparent: an implicit super-human outlook of the ruler could only serve to underpin his power-position within the state. But Augustus, having learned his lesson from Caesar’s assassination, was cautious enough not to provoke stout Republicans by turning assimilation into identification.

While there was no explicit spatial focus for the divine concept of Augustus in the capital during his lifetime, after his death he was honoured with the erection of two major sanctuaries in Rome. A sacrarium on the Palatine was consecrated in the early 30’s A.D. and later transformed into a templum under Claudius.47 Additionally, the temple of Divus Augustus, vowed by the senate in 14 A.D. on the precedent of the temple of Divus Iulius, was inaugurated as late as 37 A.D. under Caligula.48 Throughout Italy, a number of similar Augustea are attested, some of them doubtless already erected during the emperor’s lifetime.49

One of the reasons for the paramount importance of spatial foci in conceptualizing a Roman god was their relative continuity and exclusiveness. By continuity, I mean the fact that once a place was consecrated to a deity, it normally remained in its possession; by exclusiveness, that it remained exclusively in its possession. These principles were in force at least as long as the augural discipline was observed.

Earlier in the Republic, however, spatial foci of gods were not always irrevocably fixed. For instance, an existing spatial focus could be cleared by summoning a deity therefrom and relegating it to another location (exauguratio). When the Capitoline temple was built, a number of gods had to be exaugurated. However, Terminus and Iuventus (some sources also include Mars) resisted and were integrated into the new sanctuary of Iuppiter.50 In practical terms, the reluctance to relocate Terminus may well have been due to his functional focus as the god of ‘boundaries’, but function was hardly a reason for preserving the spatial focus of the worship of Iuventus (or Mars, if indeed he was involved) on this spot. Possibly, we have to include Summanus in the group of gods that could not be summoned from the Capitol.51

Under certain conditions a god could ‘trespass’ on ground consecrated to another god. One may refer, for instance, to the building of temple B (Temple of Fortuna huiusce diei, built at the end of the second century B.C.) in the same area as temple C (Temple of Iuturna[?], built in the mid-third century B.C.) in the sacred area of Largo Argentina.52 Furthermore, we know that Cn. Flavius dedicated a temple of Concordia in the Volcanal (in area Vulcani) at the end of the fourth century B.C.53 Unfortunately, in neither of the above cases is there clear evidence for the exact nature of the ‘overlap’ of spatial foci of the gods in question.

A complete abolition of a spatial focus is possible, though rare (unless the cult was officially banned, as in the case of the Bacchanalia). Cicero did actually achieve the demolition of the sanctuary of Libertas in 57 B.C. It had been erected on his private precincts by Clodius a year earlier, but had been consecrated in violation of pontifical law.54 The temple of Pietas, built and dedicated to the goddess at the beginning of the second century B.C., was apparently torn down in 44 B.C., when a theatre (the later Theatre of Marcellus) was erected on the same site.55 Whether these deities received sanctuaries located elsewhere is unknown. However, it is rather unlikely, as they are never mentioned again. Besides this, they had been established on rather flimsy political grounds and for personal reasons in the first place.

The vast majority of spatial foci of Roman cults were undeniably stable and relatively exclusive. If we concentrate on these, there is an obvious interaction between spatial and functional foci. Indeed, three categories may be distinguished here: first, gods with related functional foci and worshipped in distinct sanctuaries. Secondly, gods with related functional foci and worshipped in distinct cellae within the same sanctuary or (ignoring the augural discipline) in the same cella but in the form of different cult statues. And thirdly, gods with related functional foci that had merged to such a degree that they were worshipped as a single god in the form of a single cult statue rather than as distinct deities. In this order, the three categories represent an increasing degree of assimilation.

1. Distinct temples would normally suggest a less direct relationship of the gods in question. Such a relationship is therefore often hard to prove. It is obvious in cases where functional foci had led to hypos-tasization, for instance where a temple dedicated to a hypostasis of a major god was built in the vicinity of a temple of his/her ‘parent’ god (hyperstasis).56 Turning to the worship of distinct gods, two examples should at least be mentioned: Apollo the ‘healer’ had his temple on the bank of the Tiber. It was situated virtually opposite the temple of Aesculapius (himself a healing god of paramount importance and located on the Island in the Tiber). Also, a sanctuary of Carmenta, a goddess of birth and fertility, was situated next to the temple of Mater Matuta, a goddess of matrons, both buildings being located at the foot of the Capitol. Possibly, the two temples complemented each other also in ritual terms.57

2. The second category, i.e. distinct gods with related functional foci and housed in the same cella/temple, is much better attested. It is worth noting that in this category the functional relationship might often be expressed by fictitious links of divine kinship, adopted from—or at least modelled on—Greek concepts. I will restrict myself to the most striking case, the Capitoline triad. The combination of Iuppiter and Iuno is clearly influenced by the functional foci of the Greek couple, Zeus and Hera. Minerva, i.e. Greek Athena (Polias), as daughter of Iuppiter and—according to Greek thinking—protectress of cities par excellence, is hardly surprising within this group of tutelary gods.58 This is not to say that the triad as such originated from Greece, but that it was motivated by the interaction of functional foci of Greek gods, whatever the routes from which they arrived in Rome, and whatever the Romans eventually understood these Greek concepts to represent. Wissowa’s argument is still valid: had the triad merely been adopted from a Greek environment, one would expect its cult to be under the control of the II/X/XVviri sacris faciundis. However, this was not the case.59

A special case of divine groups that were based on complementarity of functional foci, and whose cult statues were housed next or very close to each other, were gods accompanied by their so-called divine ‘consorts’. For where complementary functional foci were sex-related and could not easily be brought into line with the existing sex-related foci of a deity, they could be subsumed under the cult of an ‘auxiliary’ deity of the other sex, which was then normally worshipped as a ‘consort’. It was not unusual for such ‘consorts’ to gain considerable independence over time. For example, Sarapis received increased popularity after the ascent of his even more popular female companion Isis in the first century A.D. He became virtually her match from the second century A.D. on. Similarly, one may cite Attis, the consort of Magna Mater, whose worship boomed in the Middle Empire. Their joint cult dates back to the Republican period, but became conspicuous only from the first century A.D. onwards.60

Another noteworthy incident of the influence of functional complementarity on the spatial setting of gods is the joint spatial conceptualization of divinized emperors. Until the end of the second century A.D., the divinity of the deceased emperor was regularly marked by a temple. But with the number of Divi increasing and available urban space dramatically shrinking, it became expedient to restrict the number of spatial foci of the imperial cult. As a consequence, cult statues of the Divi were more and more placed at existing spatial foci (aedes, templa, porticus) of earlier Divi such as that of Divus Augustus on the Palatine or Divus Titus in the Campus Martius.61

3. We have a small number of examples of the third category, the complete merger of spatial, functional and other conceptual foci of two gods. A case in point is Semo Sancus Dius Fidius.62 The latter is a composite divine name originally representing two independent deities, Semo Sancus and Dius Fidius. It was to Dius Fidius alone that a temple on the Quirinal was initially dedicated in the first half of the fifth century B.C., as borne out by the oldest written evidence.63 Thus one can accommodate more easily the information that the temple was allegedly built by Tarquinius Superbus (and consecrated by Spurius Postumius in 466 B.C.),64 while the transfer of Sancus from Sabine territory to Rome was traditionally associated with the Sabine king Titus Tatius.65 The hypaethral shape of the Quirinal temple,66 too, could well support a dedication to Dius Fidius, the god of oaths par excellence, alone, for according to Cato, it was forbidden to take an oath to the god under a roof.67 However, Semo Sancus, a god connected with lightning, would potentially be a strong candidate for a hypaethral temple as well. The fact is that in the classical period it was no longer clear which of the two deities should be addressed on the anniversary of the temple (June 5).68

Another case of such divine assimilation, albeit much less clear, might be that of Iuppiter Feretrius. Though the god could also be (and is normally) interpreted as an early Jovian hypostasis, his peculiar iconographic focus (a flint-stone) in combination with the fact that he is the only Jovian hypostasis with a clearly distinct temporal and personnel focus (ludi Capitolini, fetiales), as well as the obscure etymology of the epithet Feretrius suggest that the god is in fact the result of an assimilation of two originally distinct deities, Iuppiter and (an otherwise unknown) Feretrius. The god would then find a perfect parallel in Iup-piter Summanus and other similar cases.69

Synagogues are attested in Rome at least from the beginning of the first century A.D.70 However, the paramount spatial focus of the Jewish cult was, of course, the temple in Jerusalem with its numerous rituals performed by professional priests. When the temple was destroyed by the Romans in 70 A.D., much of its function and liturgy was transferred to the synagogues of the diaspora, whose significance as spatial foci thus considerably increased. Henceforth, the worship of the Jewish god became focused not on space (i.e. the temple in Jerusalem), but on ritual. An outcome of this spatial ‘defocalization’ of the cult of the Jewish god was the standardization of the synagogal liturgy.71

Early Christianity was initially closely bound up with Judaism, which furnished a considerable percentage of early Christian proselytes. This meant that the temple in Jerusalem must initially have been regarded by many Christian proselytes as a spatial focus of the cult of their god. However, we find already in the gospel of Mark (ca. 60–75 A.D.) the notion that the temple was nothing more than a place of prayer, a temporary building of stone, liable to destruction.72 According to the writer of Acts (ca. 80–90 A.D.), Stephen quoted Isaiah to support his view that god could not be locked up in a building.73 With the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem in 70 A.D., the Christian cult lost its spatial focus for the next two hundred years to come. Its new concept was summarized by Minucius Felix (at the end of the second century A.D.): “what temple could I built for him [scil. the Christian god], when this whole world as formed by his hands cannot contain him?”74 In a similar vein we find Justin Martyr (died 165 A.D. in Rome) saying:

“The god of the Christians is not constrained by place, but, being invisible, fills heaven and earth, and is worshipped and glorified by believers everywhere.”75

While the important members of the traditional Roman pantheon were conceptualized by spatial foci of their cults, Roman Christianity was deliberately elusive in terms of space. The only possible exception is the tomb, allegedly of Peter, found under the basilica of St Peter (where a form of veneration may possibly have taken place in the second century A.D.).76 Meanwhile, when in the middle of the second century A.D. Justin Martyr was asked by the Roman prefect where the Christians gathered in the capital, his answer was as short as it was tell-ing: “wherever each of us wants to and can. You may think we gather at one specific spot. However, you are wrong.”77 The fact seems to be that the Christian god was initially worshipped in exclusively private settings, at locations temporarily employed for religious observances, either multipurpose buildings or cemeteries. Here, meetings were convened, normally at least once a week on Sunday.78 The first instances of Christian buildings designed for permanent religious use are to be found at the beginning or middle of the third century A.D. not in the capital or Italy, but in the Roman East (Edessa, Dura Europos).79 No house-churches of any kind are so far archaeologically traceable in Rome before the early fourth century.80

This spatial elusiveness of early Christianity was not a disadvantage. In fact, it made the Christian cult virtually immune to any kind of public interference and, at the same time, a very marketable and flexible merchandise that could be ‘traded’ virtually everywhere without capital investment. I contend (and will support my contention below) that this spatial independence characteristic of the Christian cult is a main reason for the spread of Christianity in the pre-Constantine era.

In Rome—as in the rest of the Roman world—the systematic ‘spatialization’ of Christianity was virtually invented by Constantine the Great, who thus adopted the pagan practice of attributing specific space to divine concepts and applied it to his new god (clearly not only for reasons of piety). The first official Roman church was the Basilica Constantiniana (San Giovanni in Laterano) built shortly after the ruler’s formal conversion in ca. 312 A.D. The very dimensions of this build-ing were indicative of a new beginning. With a length of some 100 meters and width of almost 60, it by far surpassed the dimensions of the Republican temple of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus (ca. 62 meters × 54 meters). Holloway estimates that it could house 3,000 worship-pers.81 But not only did Constantine allocate specific urban space to his new official cult, he also set a precedent for a new architectural type of building to mark this space, the basilica. Inspired by the forms of profane civil buildings and palatial or classical hypostyle architecture, this new edificial type combined pagan traditionalism with Christian innovation. The altar, at the centre of the basilica, was a reminder of the essentially pagan spatial concept that lay behind it.82 In later years, Constantine built a church of even greater dimensions, Old St. Peter’s, which was finished around 330. It was the first basilica to be built over a tomb of a martyr,83 soon to be followed by iconographic foci of the cults of the martyrs in Rome.84 Other basilicas founded by Constantine, situated outside the Aurelian Walls, followed suit.85 Constantine’s building activities formed the beginning of the large-scale spatialization of the Christian god in the fourth century A.D. and later.86

In conceptual terms, it is fair to say that Christianity had long been space-indifferent. This indifference was due to the very doctrine of monotheism, in which any emphasis or focus on a specific space actually constituted a paradox: given the universal existence, power, and presence of the one god, it was neither reasonable nor desirable to single out specific spatial units for worship. The other cause of the Christian indifference to space was money: most early Christians did not have the financial means to make available and embellish a specific spatial area for the worship of their god. It was Constantine who had both the means and the motive for changing this situation. By introducing the notion of spatial focalization for the Christian god, he adopted the heathen attitude towards divine space.

The development of the spatial conceptualization of the concept of ‘god’ may thus be divided broadly speaking into three stages. First came paganism, characterized by a regular attribution of specific space to specific divine entities. In terms of architectural forms, such space did not differ essentially from one deity to another (if we exempt special cases such as the ‘caves’ of Mithras). The usual constituents of divine space were an altar and a temple, apart from secondary accessories more directly linked to the nature of the individual god, such as a cult statue with a specific iconography or the ‘hearth’ of the temple of Vesta. The normal way to express the gradation of importance within the hierarchy of the various gods was not architectural form, but size, building material and the technical execution of the spatial markers. Still, bulk and craftsmanship did not necessarily reflect the importance of a cult, as is immediately apparent from the inconspicuous buildings of such prodigious cults as that of Iuppiter Feretrius or the temple of Vesta. Generally speaking, it is fair to say that space transformed in order to indicate divinity (most notably also divinity of the emperor) normally remained indistinct with regard to the individuality of the gods concerned. It is this indistinctiveness that makes the work of modern archaeologists so dauntingly difficult, whenever they are called to determine the owner deity of a temple without further evidence. Scores of unidentified temple structures in cities like Ostia or Pompeii, where architectural remains abound while the epigraphical evidence is often lacking, are a case in point.

The second stage is the period from the beginning of Christianity to the reign of Constantine. This period is characterized by two competing concepts of space, the traditional pagan one and the new Christian concept of divinity without any particular reference to space. The latter had three notable advantages over its competitor: it was cheap, it was immune to foreign interference (no temples meant: no temples could be destroyed), and it was easily transferable from one place to another. On the other hand, the traditional pagan concepts of space as constituents of a ‘god’ had to compete not only with Christianity, but also with the disintegrative forces of the spatial markers of the imperial cult. One may doubt whether Christianity would have managed to eventually triumph over paganism, had it not been assisted by the dissolving forces of the imperial cult.

The last stage is inaugurated by Constantine and characterized by a synthesis of the two competing concepts of ‘spatialization’ and ‘non-spatialization’ of the divine. Constantine realized that the majority of his subjects were still pagans and that the adoption of and the emphasis on the concept of ‘space’ in conceptualizing a divine entity would facilitate a quicker conversion of the masses as well as control of their ritual activities. At the same time, he acknowledged previous Christian indifference or even aversion to spatial fixation by avoiding the traditional architectural form of the temple.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Chapter 1.1 (11-30) from Roman Gods: A Conceptual Approach, by Michael Lipka (Brill, 04.30.2009), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license.