Trump mocking a disabled reporter / Duke University, Creative Commons

President Donald Trump’s popularized “political incorrectness” has become a signifier allowing for backstage, or overt, racist sentiments to become steadily normalized as logical in the public frontstage of political discourse and social media.

By Dr. Jessica Gantt-Shafer

Associate Professor of Communication

Colorado Mountain College

Abstract

President Donald Trump’s popularized “political incorrectness” has become a signifier allowing for backstage, or overt, racist sentiments to become steadily normalized as logical in the public frontstage of political discourse and social media. This normalization is possible under the guise of neoliberal truth telling. In the current context of neoliberalism, touting postracial “colorblindness” and achieved equalities, there is subsequent Trump-backed whitelash against “political correctness,” or an acknowledgement of inequality, in US public discourse. Highly racialized public issues such as immigration and relations between the US and Mexico lead to conversations in which “politically incorrect” white-centric racialized language is used, which has roots in the narratives of neoliberal postracialism and white superiority. Thematic analyses of popular media examples of Trump’s anti-political correctness (PC) rhetoric alongside qualitatively gathered positive social media responses to his “incorrectness” on Twitter exemplify how neoliberal “postracial” ideology can be used inversely to solidify feelings of white superiority and overt racist beliefs.The continued normalization of Trump’s version of “politically incorrect” ideology and language both on and offline can lead to increased racial violence and the continued creation of neoliberal policy with racially disparate impacts.

Introduction

Greensboro Coliseum Special Events Center for a Donald Trump rally on June 14, 2016 / WUNC, Creative Commons

In January 2016, CNN produced a three minute video about first-time US voters who were “all-in for Donald Trump.” The featured voters—three young, white men—appeared delighted to have found a candidate who was not concerned with “political correctness” and was unafraid to say what they believed “ordinary citizens” in the United States think and say (CNN Politics, 2016). Two months later, in early March 2016, for twenty-four hours the public Snapchat mobile application showed live videos from Trump rallies in which similar young white men in Make America Great Again hats chanted “build that wall” outside a rally. Later, supporters inside the rally cheered in unison with Trump as he declared the wall should be “ten feet higher!” White supporters in these videos seem happy to dismiss the idea of being “politically correct,” which according to Trump hinders progress and wastes valuable time (Trump, 2016). These supporters are encouraged to believe they are speaking objective truths about issues like immigration to the dismay of the “politically correct,” who either intentionally obscure truth for political gain or have not yet faced up to reality. Donald Trump’s popularized version of “political incorrectness,” or supposed truth telling as per his supporters, embodies Feagin’s (2014) white racial frame. The white racial frame is a neoliberal worldview that “interprets and defends white privileges and advantaged conditions as meritorious” and accents white virtue in opposition to the inferiority and deficiencies of racially oppressed people of color (Feagin, 2014, p. 26). I argue Trump’s use of the term “political incorrectness,” as situated in the neoliberal white racial frame, has become a signifier in current politics as a means through which backstage, or overt, racism and bigotry can be communicated with an illusion of subtlety by white citizens in the public frontstage of social media and political discourse. Goffman’s (1959) theory of social interaction includes the frontstage, or public self, and the backstage, or the private self. Picca and Feagin (2007) extend this theory into the context of experiences with racism and racist speech in the public, multicultural frontstage and the private, ethnically homogenous backstage. In this article, I explore how Goffman’s (1959) frontstage–backstage theory, and Picca and Feagin’s (2007) use of this theory for interracial interaction, can help to more deeply conceptualize the ways in which racism is expressed on social media in a neoliberal age of “whitelash” against “political correctness” and the political establishment. This article adds to analyses of critical race theory and theories of racism as manifest in public social media in Trump’s America.

Before winning the 2016 presidential election, Donald Trump was known in popular culture as a business mogul and star of the reality television show “The Apprentice,” in which he coined the phrase “You’re fired!” to dispense of unworthy competitors in a race to prove business know-how and personal finesse. Situated in the same neoliberal, egotistical frame of personal branding and self-made success, Trump’s political messaging focused on the traditional

conservative values of “economic nationalism, controlled borders, and a foreign policy that puts American interests first” (Shenk, 2016). Trump announced he was running for president on July 16, 2015, in a speech in which he referred to his alleged business success (“I will be the greatest jobs president that God ever created”) and declared the United States had become a “dumping ground for everybody else’s problems” (TIME Staff, 2015). He also infamously stated that when Mexico “sends” immigrants to the United States, they are “sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with them. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists” (TIME Staff, 2015). While many read these racist comments as tending toward extremism, in an era ridden with fears of refugees, globalization, and the mindset that fostered Great Britain’s “Brexit” from the European Union, Trump was able to overcome criticism and emerge in the conservative white sphere as a brash straight-shooter, a neoliberal truth teller—the “politically incorrect” candidate who was going to get things done. Trump also emerged victorious as the 45th President of the United States. As situated in a pro-white worldview, using the term “political incorrectness” has become a signifier in President Trump’s political context as a means through which backstage, overt white racism, and bigotry can be communicated in the public frontstage of social media as supposed cathartic and, importantly, no-nracially motivated truth telling.

In this article, I first briefly address the long debate over “political correctness” and whether promoting certain language enables or restricts critical thinking and problem solving. I then review theories of the white racial frame, colorblind racism, aversive racism, symbolic racism, and front and backstage performances of racism as manifest in contemporary US neoliberal discourse. Next, a thematic analysis of examples of Trump’s rhetoric on “political incorrectness” and Twitter responses from supporters show how Trump’s “political incorrectness” is reified by Twitter users, which continues to normalize and reify the neoliberal and racist ideology behind the “incorrectness.” Finally, the implications of the normalization of Trump’s neoliberal, racist “incorrectness” are considered.

The Debate over Political Correctness

Greensboro Coliseum Special Events Center for a Donald Trump rally on June 14, 2016 / LSE Blogs, Creative Commons

Geoffrey Hughes (2010) notes “political correctness” entered popular lexicon in the United States in the late 1980s due to public debates on college campuses, with many politicians, public intellectuals, and students weighing in on discussion of the term (p. 3). A historical argument against “political correctness” has been one of censorship and the notion that social norms dictating what is considered respectful, inclusive, and acceptable language would hinder productive discussion about difficult issues. Additionally, there is valid concern over who gets to decide what counts as “politically correct” language (Hughes, 2010). Due to these concerns, popular news media have questioned the nature of “political correctness.” Richard Bernstein (1990) wrote in The New York Times about what some feared to be a “hidden radical agenda in university curriculums” driven by a “liberal fascism” that demanded changes such as adding minority group histories and feminist studies to core curriculum.

Scholars have also joined the debate, including Peter Drucker (1998) who asserted that, based on its history, political correctness is a “purely totalitarian concept” meant to suppress thinking not beneficial to the political aims of those in power (p. 380). Trump, like many before him, agrees with this notion. As is shown in the data, Trump often suggests being “politically correct” is not an effort to use language that includes different peoples and acknowledges systemic injustices, but rather a weak bureaucratic sugarcoating of inherent truths—pandering to populations for the sake of a political career. Even the construction of the term “political correctness” appears to assume a difference between being correct, or speaking truth, and being politically correct, or speaking for political gain. In this dichotomy, as interpreted by politicians like Trump, it would seem there is little room for inclusive and progressive ways of speaking; either you speak the blunt (white) truth or you speak politically savvy inclusive language.

However, Angela McRobbie (2009) argues the concern over “political correctness” has grown far beyond any progress made by the notion itself. She describes how the growing concern over the idea of “political correctness” entails “some sense in which quite reasonable and acceptable ideas like gender equality, ideas which most people would now find acceptable, have been somehow distorted, taken too far, abused and turned into something monstrous, dogmatic, and authoritarian” (McRobbie, 2009, p. 37).

While in theory political correctness can be wielded by those in power to silence subversive thoughts, I agree with McRobbie (2009) and posit the current interpretation of political correctness propagated by Trump suggests that reasonable ideas, like anti-racism and gender equality, have become dogmatic and monstrous. Trump’s championed “political incorrectness” and pro-white truth telling is inherently attached to practices of continued oppression and

silencing of already marginalized groups—those still without power—under the guise of evening the score against the PC police. Trump’s rhetoric denouncing “political correctness” is not a new argument, but it has been massively popularized in his campaign for the presidency.

Critical Race Theory and Contemporary U.S. Racial Discourse

OpenDemocracy, Creative Commons

In order to address the pro-white nature of Trump’s “political incorrectness,” we must first account for contemporary forms of racism that allow for white media users to proliferate his “politically incorrect” and racially charged rhetoric without a sense of shame or fear of repercussions. The term racism as used in this article is situated in Feagin’s (2014) white racial frame. This frame encompasses a racist worldview that diminishes other groups while reinforcing whiteness as superior. The white racial frame is both individually enacted, via interpersonal prejudice and racist thinking, and systematically perpetuated, via societal exclusion from institutions such as equitable education or a fair housing market (Feagin, 2014). A common individual enactment of the white racial frame can be described through Kinder and Sears’ (1981) symbolic racism, or an “abstract, moralistic resentment of blacks”—and, as a result over time, other minorities—that correlates to assumed white superiority rather than actual or perceived threats by minority groups (Kinder & Sears, 1981, p. 427).

Because whites in the United States exist in a multiracial society that has in recent decades suggested is it politically and socially correct to inhibit overt racism in the public sphere, Picca and Feagin’s (2007) study, which used students’ private journal entries about their experiences with racism, connects the white racial frame and symbolic racism to the notions of back and frontstage presentation of the self (Goffman, 1959). In his influential book, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Erving Goffman (1959) applied the analogy of theatrical performance to social interaction, noting how at the root of enacting the self in human interaction is the fear of being embarrassed or performing in a way not socially acceptable. Thus, applying Goffman’s (1959) performance framework to the racialized US context, Picca and Feagin (2007) differentiate the white performance in the backstage, a space in which it appears only whites or “whiteminded” people are present, from the performance in the frontstage, a space with “diverse and multiracial populations” as an audience (p. 16). Picca and Feagin (2007) found the white racial frame is still regularly communicated blatantly in the backstage among white peers, as white participants documented exchanges of racist jokes and epithets. However, in the multiracial frontstage, whites typically attempted to conceal racist beliefs and deferred to neoliberal language. This neoliberal frame assumes an equitable postracial society where all individuals are on equal societal footing and, thus, personally responsible for all that happens to them. To attempt to display belief in and approval of this postracial reality, there is a tendency to use “colorblind” language in the public sphere.

Bonilla-Silva (2014) describes “colorblind racism” as contemporary racism that continues despite an apparent decrease in openly racist individuals. In a colorblind racist society, there is a “historicization of the problem of racism” by whites when interacting in the multiracial frontstage (Van de Mieroop, 2016, p. 3). Rather than espousing outright and outspoken bigotry, Gaertner and Dovidio (2005) describe how whites often act as aversive racists—or progressive people who “endorse fair and just treatment of all groups” but also “unconsciously harbor feelings of uneasiness toward blacks, and thus try to avoid interracial interaction” (p. 619). When interracial interaction does occur, or frontstage interaction, aversive racists are primarily concerned with “avoiding wrongdoing in interracial interactions” and tend toward colorblind notions of racial equality to avoid acknowledging systemic injustice (p. 619). This again alludes to Goffman’s (1959) highlighted fear of embarrassing the self. In the white backstage, racial slurs and jokes can be made. In the multiracial frontstage, though, these jokes are typically avoided and, instead, colorblind language and rationale are used to understand racial difference. This aligns with the supposed dichotomy of political correctness: actual truth talk in the backstage, “political correctness” in the front.

So, if white people are averse to discussing race productively in the frontstage, yet comfortable making or allowing racist slurs, jokes, and stereotypes in the backstage, possibly only the threat of public shame keeps whites from openly discussing and having their deeply held racial beliefs exposed in the frontstage. Recent disavowals of “political correctness” by figures like Trump, however, have emboldened backstage racism to return to the frontstage. This “incorrectness” is situated in a neoliberal belief that racial (and other) equality has been achieved in the United States. Thus, if citizens believe figures like Trump who suggest racialized groups, like immigrants, are inferior in morality or achievement to the white majority, in a neoliberal reality these citizens can also believe the discrepancies are based on the racialized other’s individual and cultural inferiority to whiteness. Bringing white racism to the forefront in this manner dismisses continued structural inequality and normalizes racist thinking as logical. This bringing back of backstage racist feelings to the frontstage is justified under the guise of being honest and simply “telling it like it is,” which creates an illusion of subtlety in expressing racist interpretations of issues. An important aspect of Trump’s “political incorrectness” is this subtleness with which many white supporters believe they can communicate about race. To apply this logic to the media examples from the beginning of this article, the illusion of subtlety allows people to chant “ten feet higher” rather than racist epithets about the Latinx[1] population and immigrants. According to Trump and other “politically incorrect” speakers and citizens, the wall needs to go up and it needs to be higher—ten feet higher—in order to protect (white) America. This “politically incorrect” way of speaking positions a white racist and individualist truth as communally validated in the frontstage. The audience is not necessarily cheering against Mexicans, but rather for border security.

In Trump’s damning of “political correctness,” it is crucial again to note the “politically correct” language he renounces is not serving the powerful, as Drucker (1998) feared. Instead, Trump’s “political incorrectness” reflects a white-centric neoliberal reality and serves the dominant white US hegemony. This sense of incorrectness as truth telling allows for backstage racist sentiments to become normalized as logical in the public frontstage. Symbolic, aversive, backstage, and other contemporary manifestations of both colorblind and overt racism are already deeply problematic. Yet, immediate and grave concerns arise when the President is celebrated by white citizens as he repositions racist framing as truth telling at the forefront of public discourse.

Methods

Donald Trump’s quotes and tweets are widely distributed online and are given positive support by whites. Hundreds of tweets agreeing with Trump with regard to immigration, Mexico, and “political incorrectness” are created each day (over one dozen were created during the writing of this article). Trump referred to “political correctness” when discussing myriad issues in the 2016 presidential race, but as a focal point for data collection in this article, I focus on the issues of immigration and United States–Mexico relations. Not only were these issues consistently highlighted by Trump’s campaign, but the issue of Mexican and Latinx immigration is a focal point for racist framing due its long history of being racialized in public discourse. Mexican immigrants have been framed in US public dialogue as peon laborers turned illegal aliens (Flores, 2013). Metaphorically, Latinx immigrants have been described as a disease within the national body, a “brown tide” of floodwaters overcoming the sacred US white home, and as “lowly steerage-dwellers” weighing down the lifeboats of an already strained ship (Santa Ana, 2002, p. 293). Thus, Trump’s popular rhetoric concerning the notion of “political incorrectness” as related to Mexican and Latinx US immigration directly relates to neoliberal and racialized discourse in the United States.

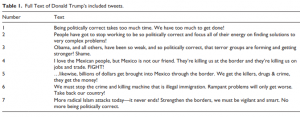

Because this article focuses on the increasing normalization of Trump’s anti-PC rhetoric in the United States on his journey from the fringe to mainstream politics, qualitative data collection was geographically restricted to the United States and only included if posted from his announcement of his candidacy on June 16, 2015, to his selection as the official Republican Party nominee on July 19, 2016. I began by seeking popular media examples of Trump’s views on “political correctness” during this period. As a sample of his “incorrectness” when discussing racialized issues, included are a January 2016 interview Trump gave on CBS’s Face the Nation, a January 2016 political ad from his campaign titled “Political Correctness,” and seven of the most popular tweets from his personal Twitter account during the data collection period referring to political correctness and United States– Mexico relations.

As daily news makes us aware, President Trump is active on Twitter. Headlines in The New York Times quote Trump’s tweets, and The Atlantic runs an active Trump Tweet Tracker, explaining the context and supposed reasoning behind each of Trump’s tweets. According to public data collected on the open Twitter analytics program Twitonomy, at the time of writing, Donald Trump’s Twitter account boasts over 29.7 million followers with 96% of his Tweets being retweeted over 16million times and 96% of his tweets being favorited by other users between December 2015 and July 2016, the time span in which Trump went from a fringe candidate to the Republican Party nominee. Trump’s included tweets have anywhere from 8,000 to 100,000 likes and retweets, which offer a glimpse into the enormous popularity of Trump’s personal account. Additionally, positive Twitter user responses to Trump’s tweets were collected to show ways in which Trump’s neoliberal “incorrectness” is supported. Like Petray and Collin (2017) in their study of Twitter users and tweets responding to #WhiteProverbs, in collecting positive responses to Trump’s tweets I did not aim for a systematic sampling of all tweets responding to or disagreeing with Trump’s “incorrectness,” nor for statistical significance (p. 3). Rather, I gathered tweets qualitatively from users interacting with Trump as a “central node” on Twitter and reifying Trump’s “political incorrectness” as part of popular political logic and discussion. On Twitter, I first searched for tweets responding to Donald Trump that included any combination of the following terms: Trump, politically correct, political correctness, immigration, and Mexico. I first utilized the “Top” public posts function of Twitter as part of this search, aiming to include highly popular Liked and Retweeted tweets responding to and supporting Trump’s “incorrectness.” In order to condense an always growing data set, I limited the search to the same time period during which I gathered media examples from Trump (June 16, 2015, to July 19, 2016). Then, every fifth public tweet containing one or more of the listed search times and responding to and supporting Trump during the data collection period was captured until a sample of 50 tweets was assembled. I then employed thematic analysis, or a method for “identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data” (Braun & Clarke, 2006, p. 6), to examine Trump’s rhetoric and the response of his supporters online. I found thematic elements in Trump’s neoliberal and racist rhetoric on “political incorrectness,” and then sought out the continuation and expansion of those themes in his supporters’ rhetoric.

Examples of Trump’s “Political Incorrectness” in the Media

Trump in a ceremony for Navajo Code Talkers in which he again chided Elizabeth Warren as “Pocahontas” / Susan Walsh, AP

I begin with examples of documented statements by Donald Trump about his approach to “political correctness,” United States–Mexico relations, and immigration. Trump’s depiction of “political correctness” suggests “PC language” disrupts neoliberal progress and beats around the bush concerning major threats to the nation. For Trump, being “politically incorrect,” or normalizing backstage racist beliefs in the frontstage, means embodying a neoliberal ideology,

facing dire realities head on, and speaking “truth” about what needs to be done to fix problems that are real and imminent. His dismissal of “PC culture” and his approach to immigration fall primarily into two themes: a sense of urgency and a need for improved national security. Both these themes resonate with deep white fears of majority–minority groups dismantling white supremacy, and in turn impacting the rationality of a white, neoliberal ideology. A sense of urgency stretches across Trump’s discussion of “political correctness,” with emphasis on the inability to get important tasks done when constantly trying to be “politically correct.” Due to an inability to discuss problems in his “incorrect” way, Trump suggests we can no longer make progress with regard to policy. In an interview on CBS’s Face the Nation in January 2016, Trump noted his Ivy League education and belief in his ability to play the political game, stating “I can be the most politically correct person with you. Here’s the problem with political correctness, it takes too long. We don’t have time. We don’t have time” (Trump, 2016). To give an example of the time and effort wasted on “political correctness,” Trump recalls a story from a news conference at which a reporter interrupted his discussion of “anchor babies,” or a pejorative term for children born in the United States with undocumented parents. The reporter told Trump the term was derogatory, and Trump asked the reporter what he should call these children instead. As Trump tells his story of their interaction, he states “[the reporter] gave me like a seven or eight word answer. I said we don’t have time for that. I’m sorry. We don’t have time for that” (Trump, 2016). The time spent on acknowledging and addressing racism in language, institutions, and ways of thinking is unnecessary and wasteful in a neoliberal reality.

Also in January 2016, Trump’s campaign created a 27-s political ad titled “Political Correctness” in a series of videos called “On the Issues” posted to his campaign website and YouTube channel. In the ad, Trump again draws attention to his education and political acumen, but states being “politically correct” and speaking in the way he was taught in the Ivy League “just takes too much time. It takes too much effort.” This effort is wasted, he says, as we have to “get things done in this country and you’re never going to get it done if we just stay politically correct” (Donald J. Trump for President, 2016). Again, in neoliberal thinking, the playing field has been equalized for all and individuals bear the responsibility of their lives, so extra time (or money) spent on “politically correct” issues, like improving relations with Mexico or creating a path to citizenship for DREAMers is wasteful.

On his Twitter feed, Trump offers regular reminders the current political system is broken due to its “political correctness” and lack of urgency and expediency. A tweet from January 2016 (see Table 1) simply reads as follows: (1) “Being politically correct takes too much time. We have too much to get done!”[2] Another tweet from December 2015 states: (2) “People have got to stop working to be so politically correct and focus all of their energy on finding solutions to very complex problems!” When examined through the neoliberal white racial frame, Trump suggests in these examples that taking time for “political correctness,” or including the experiences and concerns of non-dominant and non-white groups must be eschewed in order for (white) goals to be accomplished efficiently. As for the second theme, examples from Trump’s Twitter feed also showcase his belief that “political correctness” must be shunned in the name of national security. A tweet from March 2016 reads: (3) “Obama, and all others, have been so weak, and so politically correct, that terror groups are forming and getting stronger! Shame.” As he has repeatedly done in the public sphere, Trump sees “political correctness” as a frontstage performance by liberal politicians and their supporters that embodies a weakness—an unwillingness to speak truth. When leaders are “weak,” or do not attend to a neoliberal, white-centric worldview, Trump claims they damage national security.

In terms of the threat of non-white immigration specifically, when talking about Mexico in June and July 2015, Trump wrote on Twitter that he (4) loves “the Mexico people,” but that the United States is losing (4) “jobs and trade” to Mexico who is “not our friend.” According to Trump, Mexico is (4) “killing us at the border,” as (5) “billions of dollars get brought into Mexico through the border” while the United States gets “killers, drugs & crime.” For these reasons, Trump tweeted we (6) “must stop the crime and killing machine that is illegal immigration” and, most ominously, “take back our country.” In a succinct message in January 2016, Trump simply wrote: (7) “Strengthen the borders, we must be vigilant and smart. No more being politically correct.” These tweets about border and national security reflect the neoliberal belief that immigrants, despite being given the same opportunities and choices in life as regular US citizens, chose to break the law and come to the US out of selfishness and greed. Therefore, these immoral people might be dangerous, and it is logical that policies should be more punitive toward those who have deemed themselves unworthy through their own individual decisions. Once “political correctness” is quashed, and we stop wasting time discussing contextual factors for immigration, we can get down to business defending our prosperous, neoliberal, self-made (white) citizens.

Example of Users Echoing Trump’s “Incorrectness” Documents in the Online Frontstage

If Trump’s rhetoric was ignored, his “political incorrectness” touted in television interviews, political ads, and daily tweets might not warrant close scrutiny. However, Trump became the 45th President of the United States, and the neoliberal beliefs he espoused during his campaign are now a fixture in mainstream media and public dialogue.

Through the sample of 50 response tweets, Trump’s neoliberal “political incorrectness” and stance on immigration are echoed and expanded on by Twitter users. There is the sense of urgency to tell the “truth” and “keep” the country, and the condemnation of the naivety and weakness of “politically correct” politicians that threatens national security and subsequently the livelihood of citizens. Interestingly, some folks supporting Trump’s “incorrectness” acknowledge there were convinced to support his policies almost solely through his brash “truth telling.” While I thematically analyzed 50 total examples, I include representative quotes from 15 here, which can be viewed in their entirety in Table 2.

Of the sample of tweets responding to and supporting Trump, users echoed the need for urgency in ending “political correctness.” PC culture must be stopped quickly in order to address pressing issues such as national security, and, as one user wrote, (1) “birth rates, immigration and appeasement” of minority populations. Again, in a neoliberal mind frame, marginalized groups have been given equal opportunities (the Civil Rights movement, the

DREAM Act, minority scholarships, etc.), and, thus, are at fault for any of their own shortcomings. Therefore, politicians must stop wasting time on “political correctness,” or appealing to minority groups, and instead attend to the concerns of the (white) nation directly. Supporters mention politically correct culture must be stopped if we (2) “want to keep our country,” be able to speak without walking on (3) “politically correct eggshells,” and rid ourselves of (4) “dangerously naive politicians.” Tweets concerned with urgency and “keeping the country” undoubtedly arise from nativist and pro-white ideologies, but the tweets are attending to these ideologies without using any overtly racist language or epithets. Rather, the Twitter users are echoing Trump, and concerned with the fate of the country in the hands of current politicians who waste time either not seeing or not speaking the “truth.”

As for immigration and national security, Trump’s descriptions of politicians as naive, weak, and unable or unwilling to speak truthfully about immigrants are reiterated. One user writes politicians and the politically correct are (5) “out in force to attack Trump for telling the truth about the ILLEGAL immigrants from Mexico.” The focus on the illegality of some migrants’ crossing of the border has often been situated in a highly neoliberal frame, in which the context for the decision is negated and the decision to cross the border was simply made by an immoral individual who might potentially do other illegal or dangerous things once in the United States. When discussing these immigrants and Trump’s politically incorrect language, another user agrees Trump is being attacked simply for being honest, stating Trump (6) “makes a True statement that Mexico is sending their Human Debris across the border and the Politically Correct come out in force.” Additionally, another user acknowledges their own apparent “incorrectness” when writing in support of Trump. The tweet reads: (7) “OK this isn’t going to be Politically Correct. Do you think Mexico gives 2 sh*ts about us? They are raping our economy. VOTE TRUMP! Save USA.” These users agree Trump (8) “gives the American people a voice” and speaks a “truth” they believe has been ignored in recent political culture. The questions to be answered, of course, are: Who all is to be included in “the American people?” Whose “truth” will be amplified by Trump’s “incorrectness?” If “we” want to keep our country, who is included in us?

An interesting finding throughout the sample was a stated willingness to support Trump based solely on his “politically incorrect” truth telling and dedication to anti-PC political action. One user states they understand why some citizens might not like Trump, but you (9) “CAN NEVER SAY HE IS OFF TARGET ON IMMIGRATION.” Another user identifies in their tweet as a Democrat, but says Trump will likely get their vote because they are (10) “tired of politically correct liars.” Another tweet identifies Trump as (11) “brash, not politically correct, and a blow hard,” but the user vows they will still vote for him because he “loves our country, and will stop immigration!” Several other users state their simple belief in Trump’s ability to (12) “help THE U.S. overall in immigration, economy, and trade” and (13) improve “homeland security” through his willingness to speak and act “incorrectly.” Because he is (14) “Not a Career Politician, Not Owned, Not Politically Correct,” it seems Trump will act on the “truth” he speaks. Even as some of these tweets admit Trump is not an easy character to like or a particularly steady role model, there is still a draw to the “truth” he speaks that resonates with the users’ and their ideology.

Some of these Twitter users will argue the policy changes they desire are tied mainly to economic or national security concerns. The demand from one user, as they acknowledge their own “political incorrectness,” for a (15) “COMPLETE TIME OUT FROM ALL IMMIGRATION” is not a policy rooted in racism, but a pragmatic national security concern. Yet, the “truth” encapsulated in Trump’s pragmatic “political incorrectness” and suggested policies is one of neoliberal and racist framing. In this frame, due to cultural trends such as minority scholarship programs and an emphasis on “colorblindness” leveling the racial playing field, white citizens have proven their merit and superiority over other groups. Twitter users recognized that Trump is a politician who was willing to use neoliberal language, acknowledge this proven superiority, and center a neoliberal white-centric narrative at the federal level of US politics.

Conclusion and Implications

The implications for the normalization of backstage racism in the frontstage are vast and difficult to correlate with cultural phenomena such as the rise of Trump’s campaign and

subsequent presidency. However, many are concerned about what it means for our society if racially charged beliefs enter the public and interracial frontstage discussion under the comfortable neoliberal guise of logical thinking or truth telling. If our social interaction is performance based on trying to avoid embarrassment (Goffman, 1959), what does the mainstream acceptance and celebration of President Trump’s rhetoric mean for citizens learning what is acceptable in public dialogue? If a neoliberal, racist interpretation of truth is accepted as objective or rational by a critical mass of citizens, it becomes reasonable for politicians like Trump to, once again in US history, tout and create neoliberal policy that will continue to perpetuate a racially stratified nation. As white superiority and symbolic racism, or the abstract hatred of the other, are amplified in the frontstage, there are real implications for non-white others, including Latinx immigrants, who are steadily demonized in a neoliberal pro-white version of reality, which can lead to more hate crimes and the creation of more punitive policy.

President Donald Trump has widely popularized the notion of “political incorrectness” as truth telling, which, in actuality, normalizes backstage racist framing of issues like immigration in the public neoliberal frontstage. The idea that being “politically correct,” or acknowledging systemic oppression, ignores white concerns and panders to marginalized groups is situated in a pro-white neoliberal worldview. As previously argued, neoliberal language’s illusion of subtlety, which can be enhanced by online anonymity, might embolden people in espousing thoughts they call “politically incorrect,” rather than racist. Trump’s popularization of neoliberal “incorrectness” allows whites to more comfortably espouse racist interpretations of issues and yet still believe they are not racially motivated—or at least not entirely. Rather, like Trump on his own Twitter feed, they are motivated by neoliberal arguments of achieved racial equality and finally speaking the “truth” about groups who do not make the cut. If Trump is celebrated in the public sphere for being “politically incorrect,” an individual could also reasonably expect to be celebrated for it. The individual and the President are not bigots, as “politically correct” people might suggest, they are just speaking the “truth” and willing to do something about it. In this neoliberal version of truth, individual and systemic racism are not included.

Alex Nogales, President and CEO of the National Hispanic Media Coalition, plainly stated his views of Trump’s “incorrectness.” Speaking to his experience with hate crimes committed against the Latinx population, Nogales noted, “in the community, we know that hate speech has consequences” (Llenas, 2015). Roger C. Rocha, Jr., president of the League of United Latin American Citizens, echoed Nogales’s concerns for Trump’s disregard of the Latinx community. Rocha stated: “it is obvious that Trump’s vision of making America great does not include Latinos” (Llenas, 2015). The Foreign Relations Department of the Mexican government echoed sentiments from many trying to fight the initial tide of Trump popularity. The department stated Trump’s stances on immigration and the United States–Mexico border “reflect prejudice, racism or plain ignorance” (Mexico Slams, 2015). They continued by stating, “anyone who understands the depth of the U.S.-Mexico relationship [realizes] that those proposals are not only prejudiced and absurd, but would be detrimental to the well-being of both societies” (“Mexico Slams,” 2015).

Nonprofit, anti-racist organizations have also tracked how the renormalization of backstage racist sentiment via neoliberal framing has been affecting current US society. An annual review conducted by the Southern Poverty Law Center found that in 2015 hate and extremist groups in the United States, often identifying as anti-PC, patriotic, and anti-government, rose by 14%, with particularly “significant increases among Klan groups” (Potok, 2016). The Southern Poverty Law Center cites Trump’s campaign, which began halfway through 2015, and his popularity as contributing factors in the recent growth of white extremism and the normalization of white supremacy as a casual neoliberal reality. Additionally, in early 2016, the Southern Poverty Law Center conducted a survey of approximately 2,000 K-12 teachers to investigate the impact campaign rhetoric was having in the classroom. The survey found more than two-thirds of the teachers reported “mainly immigrants, children of immigrants, and Muslims” had “expressed concerns or fears about what might happen to them or their families after the election” (Costello, 2016). An additional third of teachers reported an increase in observed “anti-Muslim or anti-immigrant sentiment” in their classrooms (Costello, 2016).

These trends continue to be monitored into Trump’s presidency. While again it is difficult or even impossible to link findings directly to a specific cultural phenomenon like Trump’s rise to mainstream acceptability, the experiences of these teachers speak to the notion that citizens and their children might learn vicariously via a successful public figure how to express racist sentiments in ways accepted or even rewarded in public. While this article includes examples from folks on Twitter responding to, supporting, and normalizing Trump’s neoliberal, racist thoughts on immigration and the non-white other online, the implications for the normalization of white supremacist thinking across a mass of white citizens has before ripped into the physical lives of minority citizens

Future Research

Future research of these phenomena could extend into the sexist and openly misogynistic aspects of the neoliberal frame as embodied in Trump’s “political incorrectness.” As an example, an additional, infamous tweet from Trump not included in the sample referenced an interaction he had with Fox News debate moderator Megyn Kelly. He wrote: “I refuse to call Megan Kelly a bimbo, because that would not be politically correct. Instead I will only call her a lightweight reporter!” The neoliberal frame’s assumed dominance does not end with race or whiteness. The frame includes aspects of masculinity, heteronormativity, wealth, and a white US Christian hegemony that should continue to be analyzed in Trump’s “politically incorrect” rhetoric and tweets, and positive responses from his supporters online

Finally, as stated above, future research can continue to track the normalization and impacts of neoliberal thinking and, thus, backstage overt racism coming once again comfortably into the frontstage not only on Twitter but also recorded on other social media or in-person. An example of this neoliberal “truth telling” moving comfortably beyond Twitter, but still being documented via social media, could be found in Snapchat live Stories from Trump rallies. The Snapchat “Story” feature culls a stream of audience photographs and videos from a live event. On March 2, 2016, photograph and video content from people attending Trump’s campaign rallies were included as a Story for users to view. In one video, young white men are filmed jumping up and down chanting “build that wall.” In a second video, Trump is shown speaking onstage. As he directs the crowd with his hands, the crowd cheers “ten feet higher” in unison. The crowd is raucous and the person filming is also jumping up and down.

These actions are similar to other scenes at passionate political rallies, but the rhetoric displayed as acceptable and even joyful has severe implications for race relations. On Twitter, the race of the user cannot be verified. The Snapchat live videos, on the other hand, documented stark video footage of rallies where the racial make-up of the majority white crowd is difficult to ignore. Future research could consider the implications inherent in users’ willingness to move from written tweets to recorded videos, and how this willingness to show one’s face signifies how neoliberal logic provides an increasingly comfortable rationalization for overt racist behavior.

Notes

- “Latinx” is used as “the ‘x’ makes Latino, a masculine identifier, gender-neutral” (Reichard, 2015).

- Tweets are quoted and correlated to Tables 1 and 2, as exhibited by Cisneros and Nakayama (2015) in their article that also gathered and quoted publicly available Twitter data.

References

Bernstein, R. (1990, October 28). Ideas and trends; the rising hegemony of the politically correct. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1990/10/28/weekinreview/ideas-trends-the-rising-hegemony-of-the-politicallycorrect.html?pagewanted=all

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2014). Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in the United States (4th ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101.

Cisneros, J. D., & Nakayama, T. (2015). New media, old racisms: Twitter, Miss America, and cultural logics of race. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 8, 108-127.

CNN Politics. (2016, January 12). These first-time voters are allin for Donald Trump. CNN. Retrieved from http://www.cnn.com/videos/politics/2016/01/12/donald-trump-young-votersorigwx-js.cnn.

Costello, M. (2016). The Trump effect: The impact of the presidential campaign on our nation’s schools. Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved from https://www.splcenter.org/sites/

default/files/splc_the_trump_effect.pdf. Donald, J. Trump for President. (2016, January 28). Political correctness [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SYIinBKejnM&index=7&list=PLKOAoICmbyV3Q7PLQnzDfpqzXrCWRTTE8.

Drucker, P. F. (1998). Political correctness and American academe. Society, 35, 380-385.

Feagin, J. R. (2014). Racist America: Roots, current realities, and future reparations (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Flores, L. A. (2003). Constructing rhetorical borders: Peons, illegal aliens, and competing narratives of immigration. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 20, 362-387.

Gaertner, S. L., & Dovidio, J. F. (2005). Understanding and addressing contemporary racism: From aversive racism to the common ingroup identity model. Journal of Social Issues, 61, 615-639.

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Hughes, G. (2010). Political correctness: A history of semantics and culture. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Kinder, D. R., & Sears, D. O. (1981). Prejudice and politics: Symbolic racism versus racial threats to the good life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40, 414-431.

Llenas, B. (2015, August 21). Latino groups warn Trump’s immigration rhetoric could inspire more hate crimes. Fox News. Retrieved from http://latino.foxnews.com/latino/politics/2015/08/21/latino-groups-warn-trump-immigration-rhetoric-could-inspire-more-hate-crimes/.

McRobbie, A. (2009). The aftermath of feminism: Gender, culture and social change. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Mexico slams Trump’s border plan, says itreflects ‘racism or plain ignorance’. (2015, August 20). Fox News. Retrieved from http://latino.foxnews.com/latino/politics/2015/08/20/mexicoslams-trump-border-plan-says-it-reflect-prejudice-racism-orplain/?intcmp=related.

Petray, T. L., & Collin, R. (2017). Your privilege is trending: Confronting whiteness on social media. Social Media + Society, 3, 1-10. doi:10.1177/2056305117706783.

Picca, L. H., & Feagin, J. (2007). Two-faced racism: Whites in the backstage and frontstage. New York, NY: Routledge.

Potok, M. (2016, February 17). Editorial: A year of living dangerously. Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved from https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/2016/

editorial-year-living-dangerously.

Reichard, R. (2015, August 29). Why we say Latinx: Trans & gender non-conforming people explain. Latina. Retrieved from http://www.latina.com/lifestyle/our-issues/why-we-say-latinxtrans-gender-non-conforming-people-explain.

Santa Ana, O. (2002). Brown tide rising: Metaphors of Latinos in contemporary American public discourse. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Shenk, T. (2016, August 16). The dark history of Donald Trump’s rightwing revolt. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/news/2016/aug/16/secret-history-trumpismdonald-trump. TIME Staff. (2015, June 16). Here’s Donald Trump’s presidential announcement speech. TIME. Retrieved from http://time.com/3923128/donald-trump-announcement-speech/.

Trump, D. (2016, January 3). Donald Trump on political correctness: It takes too long (J. Dickerson, interviewer). YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5DoPeuOU9mg.

Van de Mieroop, K. (2016). On the advantage and disadvantage of black history month for life: The creation of the post-racial era. History & Theory, 55, 3-24.

Originally published by Social Media + Society (SM + S) (July-Sep. 2017, 1-10) under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.