From the 1630s to 1650, following the arrival of French settlers, the Wendat Confederacy faced a number of challenges.

By Linda Sioui

Anthropologist

Member, Huron-Wendat First Nation of Wendake

By Dr. Annette de Stecher

Associate Professor, Critical Museology, Visual Arts of America

University of Colorado Boulder

Introduction

From the 18th century and earlier, First Nation Wendat women of Wendake, Québec have been experts in the challenging techniques of moosehair and porcupine quill embroidery. They transform materials harvested from the land into exquisite embroidered works of art in brilliant colors and complex motifs on hide and birchbark. Beautifully worked items such as trays and moccasins can be seen in museums across the United States, Canada, and Europe.

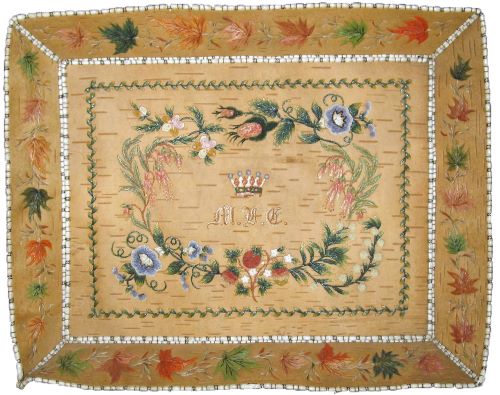

The Elgin Trays served Wendat diplomacy as adapted to the Victorian era. French fur traders and settlers were the first Europeans to arrive in the region that is today known as Québec. Following the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in Québec City on September 13, 1759, the region became a British colony. Lord Elgin was Governor General of Canada, the head of the British settler administration, from 1847 to 1854. During this period, he and Lady Elgin, his wife, each received a tray from the Wendat Nation. The trays, designed to honor the recipients, are primarily made of birch bark. Complex moosehair and porcupine quill-embroidered arrangements executed in vivid detail depict leaves and floral motifs that frame Lord and Lady Elgin’s initials and their family heraldry.

Though the trays are attributed to Wendat artist Marguerite Vincent “Lawinonkié,” there were many noted embroidery artists in Wendake, and she may have commissioned another woman to make the trays. Marguerite Vincent “Lawinonkié,” the half-sister of Grand Chief Nicolas Vincent “Tsawenhohi,” was from a family of hereditary chiefs, and she was the wife of Paul Picard “Hudawathont,” a prominent business leader from Wendake. She was born at the Bay of Quinte on the north shore of Lake Ontario in 1783. An outstanding artist and craftswoman, she mastered and taught moosehair and quill embroidery to other Wendat women and excelled at embroidery work on clothing and objects for sale.

The Wendat First Nation

Moosehair and porcupine quill embroidery have origins in the long history of the Wendat Nation, which consisted of a confederacy of several nearby nations. Their ancestral homeland was located in the area south of Lake Huron’s Georgian Bay in what is today Ontario, Canada, as well as along the shores of the Saint Lawrence River. The Wendat grew corn, squash, and beans (the “Three Sisters”), as well as tobacco. In addition to hunting on their own, they also traded their agricultural produce for game, hide, and furs with allied Indigenous nations to the north. Today the Wendat Nation is known as the “Huron-Wendat Nation.” In the early 17th century, French explorer Samuel de Champlain named these semi-sedentary and agricultural people “Huron” from the French hure for a boar’s head, alluding to the hairstyle of Wendat men.

From the 1630s to 1650, following the arrival of French settlers, the Wendat Confederacy faced a number of challenges: there were diverging interests with the arrival of Christianity; there were conflicts and wars with the Haudenosaunee; and the unfathomable tragedy of two-thirds of the Wendat population dying from smallpox within a decade. As a result, the Wendat Confederacy split up into several groups. Some were adopted by the Haudenosaunee and other neighboring First Nations. Others made their way westward to the Petun (or Tionontati), a cousin nation, to later form the Wyandotte people. Meanwhile, Wendat converts to Christianity arrived in the Québec City area, finally settling in 1697 on the site currently known as Wendake.1 According to Wendat oral tradition, the Wendat people originated from the region of the Saint Lawrence River valley before they lived on the Georgian Bay, and thus this relocation was seen as a return.2 This Wendat community—those who converted to Christianity and were living in the Québec City area—produced the magnificent moosehair and quill embroidery so admired by European newcomers.

Upon settling in the Québec City region in 1650, the Wendat resumed their farming traditions.3 However, by the early 18th century, they had begun shifting from their agricultural practices to hunting, fishing, and harvesting medicinal plants. From the 1700s, the Wendat continued their own cultural traditions and hunters traveled great distances over their territories. The community also adapted elements of French visual culture while using traditional Native materials, such as quill, moosehair, brain-tanned hide, and vegetable dyes. Wendat artists continued their ancient embroidery traditions and integrated European embroidery stitches into their repertoire, drawing on European church textiles and techniques used by theUrsuline convent nuns in Québec. The Elgin Trays are an extension of this practice.

At the start of the 19th century, European settlers and colonial authorities began appropriating Wendat lands. Wendat women realized their nation’s livelihood was threatened. They had already developed a European market for their embroidered arts in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, and they expanded this market and their traditional arts in the 19th century. By drawing on their traditional forms, they created highly successful commercial wares and souvenir arts and brought new sources of income to their community. Located on the Saint Lawrence River, a major route to the Great Lakes, Québec City was one of the main port cities in North America and provided a steady community of European buyers. Located eight miles from Québec City, the village of Lorette, later known as Village des Hurons, and today known as Wendake, became a popular tourist spot for the many visitors who flocked to Québec City. The Wendat people responded by producing moccasins, mittens, snowshoes, ash baskets, and souvenirs, which they sold to visitors.

Wendat artists produced more and more elaborate work using leather, red or black fabric, and birch bark. They embroidered complex stylized and naturalistic floral motifs on men’s and women’s clothing for ceremonial use in their community and as souvenirs. Towards the second half of the 19th century, thanks to the spirit of initiative and entrepreneurship of Marguerite Vincent “Lawinonkié,” the production of tourist art increased, ensuring Wendat families a livelihood. She was instrumental in providing Wendat families with arts and crafts work at a time when Wendat people were struggling to survive due to settler encroachment on their lands and later, colonial government regulations prohibiting access to their traditional hunting territories.

The Elgin Trays and Wendat Diplomatic Traditions

The trays memorialized the formal visits made by Wendat delegations to Lord Elgin, Lord and Lady Elgin’s visit to Lorette, and the harmonious relations between Lord and Lady Elgin and the Wendat Nation. In addition, they acted as personal souvenirs to Lord and Lady Elgin, reflecting all aspects of Wendat ceremonial arts tradition.

In Wendat diplomatic protocols presentation gifts affirmed alliances with other Indigenous nations. The Elgin Trays continued this tradition in an innovative adaptation of Wendat diplomatic artwork, designed to meet the changing circumstances caused by European settlement. The trays’ use of the heraldic thistle (which is found in the coat of arms of James Bruce, 8th Earl of Elgin), is unusual in the tradition of Wendat moosehair-embroidered bark work. The iconography of the trays, the heraldry, and the association of motifs combining Wendat traditional beliefs with motifs symbolizing European nations place these trays within the sphere of Wendat diplomacy.

Lady Elgin’s Tray

In Lady Elgin’s tray, the initials of her title appear in the center of the tray below a coronet. These initials may stand for Mary Lambton Elgin, Lambton being Lady Elgin’s family name before she married. A precisely placed border of maple leaves floats down each side panel, the leaves represent the colors of the seasons: pale green, dark green, and autumnal shades.

In the center of the tray, a border of small green leaves provides edging around a garland formed by groupings of blue morning glory, three strawberries (each at different stages of ripeness), a spray of white strawberry flowers, and what may be a rose.4 The blossoms, stems, and leaves are balanced in a play of light and dark colors, with heavy and light forms that create rhythm through regular repetition, suggesting gentle, constant movement. Strawberries and strawberry flowers are an important sacred symbol of Wendat spiritual traditions and cosmology. Elements from Lord and Lady Elgin’s coat of arms, brought together with the strawberries, demonstrates the esteem and respect of the Wendat Nation toward the recipients, as well as an alignment of both cultures in this gift.

Lord Elgin’s Tray

In Lord Elgin’s tray, each side has a border of small green leaves. In the center of the tray, the initials of his title, E & K, Earl of Elgin and Kincardine, are embroidered under an earl’s coronet. The initials are surrounded by a garland of lavender thistles and white and pink flowers, stitched with fine detail in an exquisite example of naturalistic floral style. The interconnected elements form harmonious color arrangements with a strong sense of life and movement. The thistle is the emblem of Scotland and of the Scottish Order of the Thistle. Lord Elgin, a Scotsman, was a member of this order of chivalry; by including the thistle motif the Wendat artist recognized and honored both Lord Elgin and his nation.

The Order of the Thistle is the greatest order of chivalry in Scotland. The order recognizes sixteen Knights with the highest honor in the country and Scottish men and women who have held public office or who have contributed in a particular way to national life.

The coronets and initials demonstrate Wendat familiarity with European heraldry, and the association of thistle and strawberry suggests they were also familiar with the symbolic meanings Europeans associated with flowers.5 Lord and Lady Elgin would have recognized the thistle motif and the coronets’ heraldic notation, and, as Wendat presentation speeches that accompanied gift giving often explained the symbolic meanings of gifts, they may also have had some understanding of the significations of the strawberry flowers, symbolizing understanding between two national identities.6

Diplomatic Guests: Lord and Lady Elgin Visit Chief Francois-Xavier Picard “Tahourenché”

The trays, which were received by Lord and Lady Elgin between 1847 and 1854, were an important diplomatic gift at a pivotal time in relations between the British colonial government and Indigenous communities. Between 1837 and 1854 a major shift took place in colonial policy toward Indigenous peoples in Canada, the consequences of which are felt today. Colonial legislation attempted to move Indigenous peoples from a nation-to-nation relationship and a position as military allies essential to the stability of the British colony in North America, to a position as subjects. The British colonial government was focused on policies of assimilation and moving toward industrial schools, the forerunners of residential boarding schools. In this same period, late 18th-century educational strategies and early 19th-century land rights strategies initiated by Wendat chiefs moved forward, as community members worked to further Wendat interests and boundaries of geography and culture. Wendat and British interests were in opposition. The Elgin Trays, as diplomatic gifts, followed Wendat traditions to maintain good relations with allied nations.

Residential schools were church-run and government-administered institutions that aimed to assimilate Indigenous children into settler-colonial society by removing them from their families and communities. Day schools were government-run, on-reserve institutions attended by children during the day. Residential and day schools composed of segregated, federally administered systems that caused lasting cultural harms and trauma in Indigenous communities. Survivors of both types of institutions have been part of settlement agreements with the federal government to compensate for the harms experienced.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Étienne-Thomas Girault de Villeneuve, “Des Hurons,” The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents. Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New-France, 1610–1791, volume LXX, edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites (Burrows, Cleveland: 1900 [1762]), pp. 204–09.

- Jean-François Richard, “Territorial Precedence,” Ontario Archaeology, volume 96 (2016), pp. 29, 30. See also Jonathan Lainey, “Les liens historiques des Hurons-Wendats avec les Iroquoiens de Saint-Laurent: Une réflexion,” Les Iroquoiens du Saint-Laurent: Peuple du maïs, edited by Roland Tremblay (Montréal: Pointe à Calliéres et les Editions de l’Homme, 2006), pp. 128–29.

- Denis Delâge, “La tradition de commerce chez les Huron de Lorette,” Recherches Amérindiennes au Québec, volume 30, number 3 (2000), p. 35.

- William A. Niering and Nancy C. Olmstead, National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Wildflowers (New York: Alfred K. Knopf, 1995), p. 475.

- Ruth Phillips, Trading Identities: The Souvenir in Native North American Art from the Northeast, 1700–1900 (Montreal; Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1999), pp. 182–88.

- Marguerite Vincent Tehariolina, La Nation huronne (Québec: Editions du Pélican, 1984), pp. 322–29.

Bibliography

- Canadian Museum of History

- Watch Linda Sioui, “The Huron-Wendat Craft Industry from the Nineteenth-Century to Today”

- Denis Delâge, “La tradition de commerce chez les Huron de Lorette,” Recherches Amérindiennes au Québec, volume 30, number 3 (2000), pp. 35–51.

- Annette De Stecher, Wendat Women’s Arts (Montreal; Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2022).

- Girault de Villeneuve and Étienne-Thomas, “Des Hurons,” The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents: Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New-France, 1610–1791, volume LXX, edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites (Cleveland: Burrows Publishing, 1901), pp. 204–09.

- Ruth Phillips, Trading Identities: The Souvenir in Native North American Art from the Northeast, 1700–1900 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1998).

- Marie-Paule Robitaille, “Vêtement d’appartenance,” Continuité, number 146 (2015), pp. 46–49.

- Georges E. Sioui, Huron-Wendat: The Heritage of the Circle (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1999).

- Linda Sioui, La Réaffirmation de l’Identité Wendate / Wyandotte à l’heure de la Mondialisation (Wendake: Editions Hannenorak, 2012).

- Bruce Trigger, Children of Aataentsic: A History of the Huron People to 1660 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1976).

Originally published by Smarthistory, 05.09.2024, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.