The origins, rise, regulation, and persistence of monopolies in the United States.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The history of monopolies in the United States is a saga of economic ambition, political pushback, legal innovation, and the perpetual tension between free enterprise and market control. From the industrial giants of the 19th century to the digital behemoths of the 21st, monopolistic practices have shaped the trajectory of American capitalism, sparked antitrust movements, and fueled ongoing debates about the balance between economic efficiency and public interest. Here I explore the origins, rise, regulation, and persistence of monopolies in the United States.

Early Foundations: Monopoly Fears in a New Republic

The apprehension toward monopolies in the early United States was deeply rooted in colonial experience and Enlightenment ideals. American colonists had long resented the monopolistic privileges granted by the British Crown to companies such as the East India Company, which controlled vast swaths of trade and imposed taxes without local consent. This legacy of economic concentration under monarchical rule shaped the new nation’s suspicion of concentrated economic power. The Founding Fathers, many influenced by classical republicanism, viewed monopolies not only as threats to free markets but also to political liberty, fearing that unchecked economic dominance could translate into tyranny. Thomas Jefferson famously warned against the “interests of wealth and power” that might coalesce to undermine the democratic project, emphasizing that economic pluralism was essential for political freedom.1

During the nascent years of the Republic, the economy was largely agrarian and decentralized, limiting the scope and scale of monopolistic enterprises. Nevertheless, some state governments granted exclusive charters or privileges to corporations for infrastructure projects such as turnpikes, canals, and ferries, which were often considered natural monopolies due to the high costs of entry and management. These charters, while limited in duration and scope, occasionally sparked local opposition rooted in fears that they would give undue influence to private interests at the expense of public good. The balance between encouraging economic development through infrastructure and preventing monopolistic exploitation became a key concern, especially as the nation sought to connect its vast territories and foster commerce.2

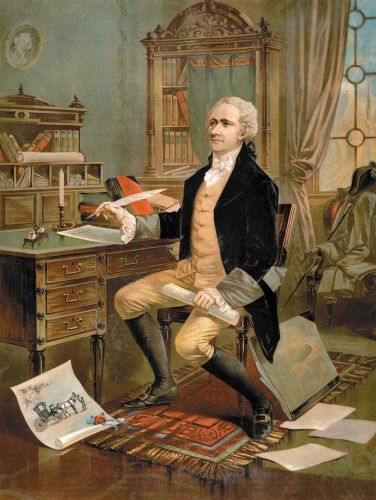

Moreover, the early legal and political frameworks of the United States reflected a cautious approach to economic concentration. The Constitution itself did not explicitly address monopolies, but its grant of commerce power to Congress opened the door for future regulatory action. Early debates in the First Congress about trade regulation, tariffs, and navigation laws hinted at an underlying unease with market domination. Influential thinkers like Alexander Hamilton advocated for a strong federal government to nurture industry and commerce but also warned against the dangers of corporate collusion and monopolistic schemes. These tensions underscored the ambivalence in early American political economy between encouraging growth and guarding against the concentration of market power.3

The memory of British monopolies and mercantilist policies also informed early American attitudes toward economic regulation. Many in the new republic equated monopolies with the abuses of the colonial period, associating them with privilege, corruption, and the subversion of free enterprise. This suspicion was not merely economic but deeply political, tied to the revolutionary ideals of equality and republicanism. As such, early state and local governments experimented with laws that prohibited monopolistic practices, although enforcement was uneven and often limited by the practical realities of the economy. The result was a patchwork of early anti-monopoly sentiments that would later crystallize into more comprehensive federal policies.4

The philosophical foundations laid in this period helped shape the Progressive Era’s later assault on trusts and monopolies. The early republic’s fear of concentrated economic power became institutionalized in legal doctrines and public attitudes, contributing to the emergence of antitrust legislation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By linking economic concentration to threats against democracy itself, the new nation established a legacy that would inform debates about market regulation for centuries. This foundational period thus set the stage for the complex interplay of corporate power, government intervention, and public interest that characterizes the American experience with monopolies.5

The Gilded Age and the Rise of Corporate Giants

Overview

The Gilded Age, spanning roughly from the 1870s to the turn of the 20th century, was marked by extraordinary economic expansion and the rapid consolidation of industries under the control of a small number of powerful corporate leaders. This period witnessed the transformation of the United States from a predominantly agrarian society to an industrial superpower, fueled by innovations in steel production, oil refining, railroads, and finance. Central figures such as John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and J.P. Morgan became emblematic of this era’s economic might. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, in particular, came to dominate the oil industry by employing aggressive tactics such as horizontal integration—buying out competing refineries—and vertical integration—controlling every stage from extraction to distribution. By the 1880s, Standard Oil controlled more than 90 percent of the oil refining capacity in the United States, effectively monopolizing the market and exerting enormous influence over prices and supply.6 Meanwhile, Andrew Carnegie revolutionized the steel industry by introducing new production methods and consolidating operations to achieve unprecedented economies of scale. His company eventually became U.S. Steel after a merger orchestrated by J.P. Morgan in 1901, forming the first billion-dollar corporation in American history.7 These industrial giants capitalized on the relative absence of federal regulation and leveraged legal mechanisms such as trusts to coordinate operations and stifle competition, fostering an environment where economic power was centralized to an extraordinary degree.

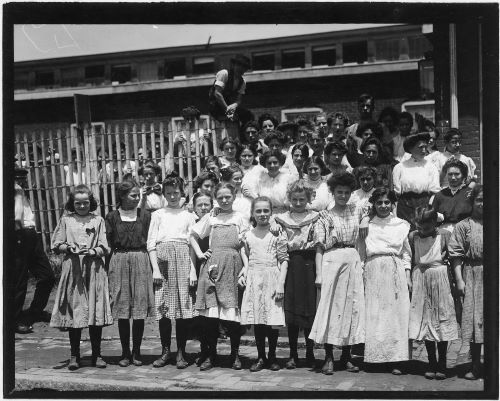

The immense concentration of wealth and corporate power during the Gilded Age provoked significant social and political backlash. Critics labeled these titans of industry “robber barons,” accusing them of exploitative labor practices, ruthless competition, and manipulation of markets to enrich themselves at the public’s expense. The monopolistic behavior of trusts, including collusive price-fixing and barriers to market entry, stifled innovation and harmed consumers, fueling growing demands for government intervention. This period also saw the rise of labor unions and populist movements that challenged the dominance of big business and called for reforms to curb corporate excesses. Politically, the federal government began to respond with legislation aimed at regulating monopolies, most notably with the passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890. Although initially weakly enforced, this law laid the groundwork for future efforts to dismantle monopolies and restore competitive markets. The Gilded Age thus represents a crucial era in American economic history, illustrating both the extraordinary capacities of industrial capitalism and the urgent need for regulatory frameworks to balance private power with the public interest.8

The following men formed “trusts,” conglomerates that allowed companies to legally coordinate operations and fix prices without formally merging. The rise of trusts led to higher consumer prices, stifled competition, and corruption in government through lobbying and favoritism.

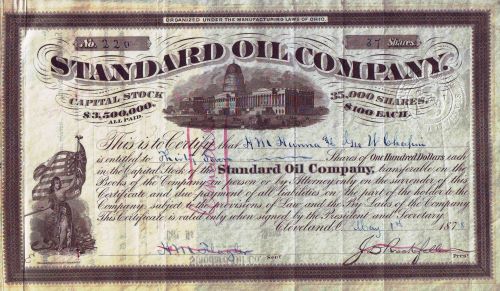

John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil

John D. Rockefeller, often regarded as the quintessential industrial titan of the Gilded Age, built Standard Oil into one of the most powerful and controversial corporations in American history. Founded in 1870, Standard Oil grew rapidly through a combination of ruthless business tactics and innovative management strategies. Rockefeller’s approach to business emphasized efficiency, cost-cutting, and aggressive consolidation. He pioneered the use of horizontal integration by systematically buying out competing refineries to control market share and eliminate competition. Equally important was his application of vertical integration—Standard Oil gained control over every aspect of the oil supply chain, including production, transportation, refining, and distribution. This comprehensive control enabled the company to drastically reduce costs and undercut competitors on price.9 Rockefeller also employed secret rebates and preferential rates from railroads to further disadvantage rivals, tactics that sparked public outrage and accusations of unfair competition. Through these methods, Standard Oil came to dominate nearly 90 percent of the U.S. oil refining industry by the 1880s, positioning Rockefeller as one of the wealthiest men in the world and cementing the company’s near-monopoly on the oil business.10

The immense concentration of economic power in Standard Oil and Rockefeller’s personal fortune made him a lightning rod for criticism. Public perception of Standard Oil oscillated between admiration for its efficiency and innovation and condemnation of its monopolistic practices. Reformers and journalists, including Ida Tarbell, one of Rockefeller’s fiercest critics, exposed the company’s ruthless tactics in her groundbreaking 1904 work, The History of the Standard Oil Company. Tarbell’s detailed investigation illuminated the opaque operations and anti-competitive strategies that allowed Standard Oil to crush rivals and control prices, galvanizing the growing public demand for regulation. In response to mounting political pressure and legal challenges, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1911 that Standard Oil violated the Sherman Antitrust Act and ordered its dissolution into 34 independent companies. Despite this breakup, many of these successor companies, such as ExxonMobil and Chevron, remain dominant players in the global energy sector, underscoring Rockefeller’s enduring legacy in shaping modern corporate America.11

Andrew Carnegie and U.S. Steel

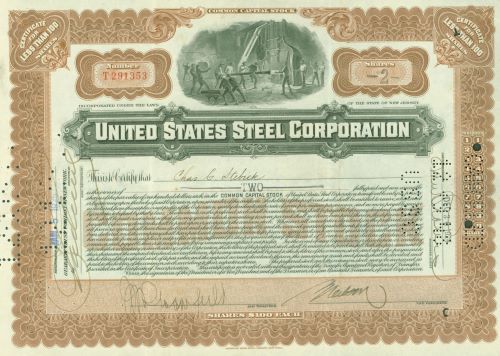

Andrew Carnegie emerged as the dominant figure in the American steel industry during the late 19th century, revolutionizing production and business organization. Carnegie’s rise was propelled by his mastery of the Bessemer process, which allowed steel to be produced more quickly and cheaply than before. His company, Carnegie Steel, aggressively pursued vertical integration by controlling every stage of production—from iron ore mines and coal fields to railroads and shipping lines—thereby reducing costs and improving efficiency. Carnegie was also known for his innovative management techniques, emphasizing cost-cutting, technological advancement, and economies of scale. By the 1890s, Carnegie Steel had become the largest and most profitable industrial enterprise in the world, supplying steel to rapidly growing sectors such as railroads, construction, and manufacturing.12 Carnegie’s business practices, however, were not without controversy; his ruthless approach to labor relations culminated in the violent 1892 Homestead Strike, which exposed tensions between capital and labor during the Gilded Age. Despite these conflicts, Carnegie’s success symbolized the transformative power of industrial capitalism and laid the groundwork for the modern steel industry in America.13

In 1901, Andrew Carnegie sold his steel empire to the financier J.P. Morgan for $480 million, one of the largest business deals in history at the time. This sale led to the creation of U.S. Steel, the first billion-dollar corporation in the United States, with Morgan orchestrating the consolidation of Carnegie Steel with several other steel companies. U.S. Steel quickly became a dominant force in the industry, controlling about two-thirds of the nation’s steel production. Under Morgan’s leadership, the corporation epitomized the era’s trend toward industrial consolidation and the formation of monopolies or oligopolies, raising new concerns about corporate power and market competition. U.S. Steel’s creation marked a turning point in American business, showcasing the tremendous scale and concentration of capital that defined the early 20th-century economy. It also set the stage for increasing government scrutiny and antitrust efforts, which sought to balance the benefits of large-scale production with the risks of monopolistic dominance.14

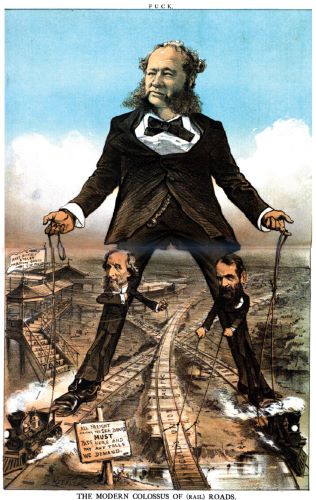

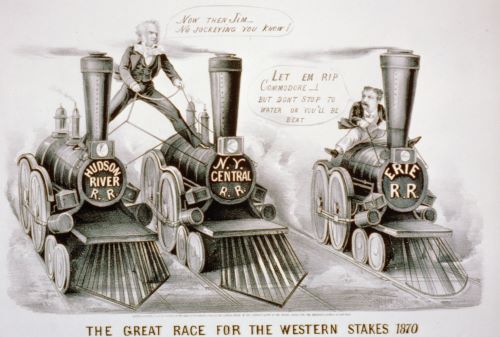

Cornelius Vanderbilt and the Railroad Empire

Cornelius Vanderbilt, often dubbed the “Commodore,” was a towering figure in the 19th-century transportation industry who played a crucial role in shaping America’s railroad system. Originally making his fortune in steamboats, Vanderbilt shifted his focus to railroads in the 1860s, recognizing the transformative potential of rail transport in the rapidly industrializing nation. He aggressively consolidated several competing lines to create a more efficient and expansive network, reducing costs and improving reliability. His most significant achievement was the creation of the New York Central Railroad, which connected New York City with the Great Lakes region and was pivotal in facilitating commerce and passenger travel across the Northeast and Midwest. Vanderbilt’s approach to business was characterized by his fierce competitiveness and strategic vision, which included cutting fares to outmaneuver rivals and investing heavily in infrastructure improvements such as better tracks and faster trains. His leadership helped to standardize and modernize railroad operations during a critical period of economic growth, fostering greater regional integration and fueling the expansion of American markets.15

Despite his successes, Vanderbilt’s railroad empire was not without controversy. His monopolistic tactics, including ruthless price wars and secret rebates, often sparked public outcry and legal challenges. Vanderbilt’s dominance over key transportation corridors enabled him to exert enormous influence over commerce and politics, raising early concerns about the concentration of economic power in private hands. His business practices contributed to the broader pattern of railroad consolidation in the Gilded Age, which eventually led to increased calls for government regulation. The Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, the first federal law to regulate railroads, emerged in part as a response to the abuses and excesses exhibited by powerful railroad magnates like Vanderbilt. Although Vanderbilt died in 1877, his legacy endured through the vast railroad networks he forged, which became the backbone of America’s industrial economy and set precedents for corporate organization and control in the decades that followed.16

J.P. Morgan: Banking Power and Industrial Consolidation

John Pierpont Morgan was one of the most influential financiers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, whose banking empire played a critical role in shaping the trajectory of American capitalism. Morgan’s approach combined vast financial resources with strategic vision to stabilize and consolidate fragmented and struggling industries. Unlike many industrial magnates who built wealth through direct production, Morgan specialized in high finance, underwriting, and corporate restructuring. His firm, J.P. Morgan & Co., became the preeminent banking institution in the United States, serving as a central force behind major mergers and acquisitions that created industrial giants. Morgan was instrumental in orchestrating the consolidation of competing firms, exemplified by his leadership in the formation of U.S. Steel in 1901—the first billion-dollar corporation—which combined Andrew Carnegie’s steel operations with several other companies into a vast monopoly. This pattern extended beyond steel to railroads, electricity, and finance, where Morgan’s interventions often prevented bankruptcies and market panics by injecting capital and reorganizing debt, stabilizing markets and enabling growth.17

Morgan’s dominance in banking and corporate consolidation was not without controversy, however. His immense power sparked fears about the concentration of economic influence in the hands of a few financiers, leading to growing public and governmental scrutiny. Morgan’s role during the Panic of 1907, when he personally coordinated efforts by bankers to shore up collapsing institutions and restore confidence in the financial system, underscored both the indispensability and risks of such concentrated control. Critics argued that Morgan’s oligarchic grip over key sectors hindered competition and threatened democratic oversight of the economy. These concerns contributed to the early 20th century’s progressive push for financial regulation, culminating in legislation such as the Federal Reserve Act of 1913, which aimed to create a more transparent and controlled banking system. Nevertheless, J.P. Morgan’s legacy remains foundational in the history of American finance, symbolizing the power and complexity of modern capitalism during a period of rapid industrial expansion and corporate transformation.18

James Buchanan Duke and the Tobacco Industry

James Buchanan Duke was a pivotal figure in the transformation of the American tobacco industry at the turn of the 20th century. Duke’s success stemmed largely from his innovative approach to cigarette manufacturing and aggressive business consolidation. Early in his career, he recognized the potential of the cigarette as a mass-market product, especially with the advent of the Bonsack machine, which mechanized cigarette production and drastically lowered costs. Duke quickly adopted this technology, enabling his company to produce cigarettes on an unprecedented scale and outcompete smaller rivals. His vision extended beyond manufacturing; he strategically invested in marketing, pioneering advertising campaigns that increased cigarette consumption nationwide. By the 1890s, Duke’s firm had become the dominant player in tobacco manufacturing. He also aggressively pursued horizontal integration, consolidating competing companies under the American Tobacco Company umbrella, which by 1890 controlled nearly 90 percent of the cigarette market.19 This consolidation not only brought enormous wealth to Duke but also intensified public concerns about monopolies and corporate power in everyday consumer goods.

The dominance of Duke’s American Tobacco Company triggered significant legal and political backlash, culminating in landmark antitrust actions. Like Standard Oil, the American Tobacco Company became a symbol of monopoly excess, accused of using predatory pricing, secret rebates, and other anti-competitive tactics to crush competition and control supply chains. The 1911 Supreme Court ruling that found the company in violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act led to its breakup into several regional firms, marking a significant moment in the federal government’s efforts to regulate monopolies and restore competitive markets. Despite the dissolution, the companies that emerged from the breakup continued to influence the tobacco industry for decades, and Duke’s legacy as a business innovator and titan of industry remains influential. His ability to combine technological innovation, strategic marketing, and aggressive consolidation exemplifies the complex dynamics of monopoly power in America’s Gilded Age economy.20

The Progressive Era and Antitrust Action

Overview

Public outcry against the unchecked power of monopolies gave rise to the Progressive Era (1890s–1920s), a transformative period in American history marked by widespread social, political, and economic reform. Alarmed by the dominance of corporate titans such as Standard Oil, U.S. Steel, and the American Tobacco Company, reformers, journalists, and politicians began to rally against the perceived injustices and corrupting influence of concentrated economic power. Muckraking journalists like Ida Tarbell and Upton Sinclair exposed the exploitative practices and unethical behavior of major corporations, galvanizing public opinion and fueling demands for change. Politicians such as President Theodore Roosevelt responded by embracing a more active role for the federal government, promoting policies aimed at trust-busting, regulating industry, and protecting consumers and workers. Landmark legislation, including the Sherman Antitrust Act and later the Clayton Antitrust Act, was passed to curb monopolistic practices and restore competitive markets. These efforts reflected a broader societal push for transparency, accountability, and fairness in both business and government, laying the groundwork for modern regulatory frameworks and a more balanced relationship between private enterprise and public interest.

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890

The Sherman Antitrust Act, enacted by Congress in 1890, was the first major piece of federal legislation aimed at curbing the power of monopolies and maintaining competitive markets in the United States. Named after Senator John Sherman of Ohio, a prominent advocate for economic fairness, the Act reflected growing public and political concern over the rise of powerful trusts that stifled competition and manipulated markets for their own gain. It declared illegal “every contract, combination… or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States,” as well as attempts to monopolize any part of interstate or foreign trade.21 While the language of the law was intentionally broad to allow for judicial interpretation, it initially lacked clear mechanisms for enforcement and was often applied inconsistently. Nevertheless, the passage of the Act marked a significant shift in the federal government’s role in regulating the economy, laying a legal foundation for future antitrust actions and demonstrating a new willingness to challenge the dominance of corporate giants.22

Despite its symbolic importance, the Sherman Act was initially weak in practice. Federal courts often interpreted its provisions narrowly, and early enforcement efforts were sporadic. In fact, in the 1895 United States v. E.C. Knight Co. case, the Supreme Court ruled that manufacturing was not considered interstate commerce and therefore outside the Act’s jurisdiction—an interpretation that severely limited its impact.23 However, the political climate began to shift with the rise of the Progressive Era, particularly under President Theodore Roosevelt, who used the Act more aggressively to break up monopolies like the Northern Securities Company in 1904. Over time, the Sherman Act evolved into a central tool for trust-busting and maintaining economic fairness, especially as it was later supplemented by stronger measures such as the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 and the Federal Trade Commission Act. While originally a blunt and underutilized instrument, the Sherman Act ultimately became a cornerstone of American antitrust policy and a defining feature of the federal government’s efforts to preserve competition in the face of growing industrial consolidation.24

Theodore Roosevelt and the “Trust Buster”

Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th President of the United States, earned the nickname “Trust Buster” for his unprecedented efforts to regulate large corporations and curb the power of monopolies during the Progressive Era. Although Roosevelt did not oppose big business in principle—he believed in its efficiency and inevitability in a modern industrial economy—he insisted that it must operate within the bounds of public accountability and fairness. His administration drew a distinction between what he termed “good trusts” that acted responsibly and “bad trusts” that exploited the public and stifled competition. Roosevelt’s most famous antitrust action came in 1902 when his Justice Department filed suit against the Northern Securities Company, a massive railroad trust controlled by J.P. Morgan, James J. Hill, and E.H. Harriman. The Supreme Court ruled in 1904 that the company violated the Sherman Antitrust Act, forcing it to dissolve—an outcome that stunned the financial elite and signaled a new era of federal intervention.25 This bold move won Roosevelt popular acclaim and firmly established the executive branch’s power to challenge corporate consolidation.26

Roosevelt’s trust-busting campaign was not limited to symbolic gestures; it marked a fundamental shift in the federal government’s regulatory posture. Under his presidency, 44 antitrust suits were brought against powerful corporations, including American Tobacco, Standard Oil, and several beef and railroad companies. Yet Roosevelt also supported the idea of regulating corporations rather than simply dismantling them, believing that federal oversight through newly empowered agencies could ensure responsible corporate behavior. His support for the creation of the Department of Commerce and Labor in 1903, which included a Bureau of Corporations tasked with investigating monopolistic practices, reflected his pragmatic approach to reform.27 Roosevelt’s actions helped redefine the relationship between business and government, moving beyond laissez-faire policies toward a model in which the state served as a referee in the marketplace. His legacy as a trust buster thus lies not only in the number of cases prosecuted but in the broader assertion that corporate power must be balanced by the public interest—an idea that would shape American regulatory policy well into the 20th century.28

The Clayton Antitrust Act and the Federal Trade Commission

The Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 was passed as a supplement to the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, aimed at strengthening federal antitrust enforcement and addressing the legal loopholes that allowed monopolistic practices to persist. Drafted by Alabama Congressman Henry De Lamar Clayton, the Act clarified and expanded the prohibitions outlined in the Sherman Act, explicitly outlawing price discrimination, exclusive dealing contracts, tying agreements, and mergers or acquisitions that substantially lessened competition or created a monopoly.29 One of its most significant provisions was the exemption of labor unions and agricultural organizations from being considered illegal combinations in restraint of trade—a response to years of judicial hostility toward organized labor under the Sherman Act. This protection, championed by progressive politicians and labor leaders, helped shift the balance of power slightly in favor of workers and farmers, reflecting the broader Progressive Era ethos of curbing corporate abuse and protecting democratic values.30 Although the law was not a panacea, it represented a critical evolution in antitrust policy by targeting specific behaviors and closing regulatory gaps that corporate lawyers had previously exploited.

Alongside the Clayton Act, Congress also created the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in 1914 through the Federal Trade Commission Act. The FTC was established as an independent federal agency tasked with preventing unfair methods of competition and deceptive business practices. Unlike earlier enforcement mechanisms that relied primarily on court action, the FTC provided a more proactive and investigative approach to antitrust regulation. The Commission was granted broad authority to issue cease-and-desist orders, conduct investigations, and monitor corporate conduct, offering a more flexible and administrative alternative to litigation.31 Under President Woodrow Wilson, who viewed economic regulation as essential to safeguarding democracy, the FTC embodied the Progressive vision of a modern regulatory state equipped to manage the complexities of industrial capitalism.32 Over time, the FTC became a cornerstone of American economic oversight, adapting its scope to new market realities such as advertising, data privacy, and digital commerce. Together, the Clayton Act and the FTC marked a maturation of antitrust policy, signaling the federal government’s deeper commitment to economic fairness and institutional accountability in the face of corporate concentration.

Mid-20th Century Consolidation and Regulation

Overview

The Great Depression and World War II shifted the federal government’s focus from antitrust enforcement to economic stabilization. While large corporations remained dominant, the postwar boom relied on regulated capitalism and strong labor protections.

United States v. AT&T (1974–1982)

The landmark antitrust case United States v. AT&T (1974–1982) marked a pivotal moment in the evolution of antitrust enforcement in the modern era, targeting one of the most powerful and entrenched monopolies in American history. For much of the 20th century, the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T) had maintained a government-sanctioned monopoly over the nation’s telephone service. Through its control of both local and long-distance networks, as well as its ownership of Western Electric and Bell Labs, AT&T exercised near-total dominance over telecommunications infrastructure, manufacturing, and innovation. By the 1970s, however, technological changes and rising consumer complaints prompted renewed scrutiny. The Department of Justice filed suit in 1974 under the Sherman Antitrust Act, alleging that AT&T had used its monopoly power in local telephone services to stifle competition in the emerging markets for telecommunications equipment and long-distance services, thus violating antitrust laws.33 The case was poised to be one of the most complex in antitrust history, involving thousands of documents, expert witnesses, and an industry central to national communications.

Rather than proceed with a lengthy trial, AT&T and the federal government reached a consent decree in 1982, fundamentally reshaping the telecommunications landscape. Under the agreement, AT&T agreed to divest its 22 local Bell Operating Companies, resulting in the creation of seven Regional Bell Operating Companies—often called the “Baby Bells.” In exchange, AT&T retained its long-distance services and equipment manufacturing arm, Western Electric.34 The breakup, which took effect on January 1, 1984, was hailed as a victory for antitrust enforcement and competition. It opened the door to new market entrants, spurred innovation, and played a foundational role in the development of the modern internet and mobile communications industries. Critics, however, argued that the fragmentation led to service inefficiencies and consumer confusion in the short term, and that telecommunications would again become concentrated through mergers in the decades that followed. Nonetheless, United States v. AT&T became a defining case in the history of antitrust law, demonstrating that even century-old, quasi-public monopolies were not immune from government intervention when competition and innovation were at stake.35

U.S. v. IBM (1969–1982)

The antitrust case United States v. IBM, filed in 1969, was one of the longest and most complex legal battles in American antitrust history. The U.S. Department of Justice accused International Business Machines Corporation (IBM) of engaging in monopolistic practices in the electronic data processing (EDP) market, specifically mainframe computers, which were the dominant computing systems at the time. The government alleged that IBM had systematically used its size and market power to exclude competitors, notably by bundling hardware, software, and services in ways that made entry difficult for smaller firms.36 At its height, IBM controlled nearly 70% of the mainframe computer market, and the government feared that such dominance threatened innovation, pricing, and market diversity. The suit, filed under the Sherman Antitrust Act, sought the divestiture of parts of IBM and other structural remedies to restore competition.37 However, the case proceeded slowly, partly due to the complexity of the technology involved and the sheer volume of evidence—over 100 witnesses testified, and the trial record exceeded 100,000 pages.

After 13 years of litigation, the Justice Department abruptly dropped the case in 1982, concluding that market conditions had changed enough to make the pursuit of a legal remedy unnecessary. By then, the computing industry was evolving rapidly, with the rise of minicomputers, personal computers, and new competitors like Digital Equipment Corporation and Apple eroding IBM’s dominance. Critics argued that the case had been overtaken by technological shifts and that the government had failed to articulate a clear remedy, while others contended that the prolonged legal pressure may have curbed IBM’s most aggressive competitive practices even without a formal judgment.38 Some economists and legal scholars viewed the case as a cautionary tale of the limits of antitrust litigation in fast-moving technology sectors, where the pace of innovation can outstrip regulatory processes. Still, U.S. v. IBM remains historically significant as an example of the federal government’s willingness to challenge a tech giant long before the digital age. It also set important precedents for how courts and regulators approach competition issues in industries defined by complex, evolving technologies.39

The Rise of Deregulation and Neoliberalism

The late 1970s and early 1980s marked a significant shift in U.S. economic policy, characterized by a growing embrace of deregulation and the rise of neoliberal economic thought. Neoliberalism, a term popularized in political and academic discourse, describes a set of policies that favor free-market capitalism, reduced government intervention, privatization, and deregulation. Although the intellectual roots of neoliberalism can be traced to postwar economists like Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman, its ascent in American policymaking accelerated during the presidencies of Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan.40 Carter, often seen as a transitional figure, oversaw the deregulation of key industries such as airlines, trucking, and railroads, arguing that excessive government control stifled innovation and competition. These moves were supported by economists across the political spectrum and represented a growing consensus that certain New Deal-era regulations had become outdated in a rapidly changing global economy.41

Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980 marked the full-throated embrace of neoliberal ideology at the federal level. Reagan’s administration launched a concerted campaign to scale back regulatory oversight, cut taxes, and promote market-driven solutions to economic challenges. His economic team, influenced heavily by supply-side economics, argued that reducing the size and scope of the federal government would unleash entrepreneurial energy and drive economic growth. Reagan famously declared in his inaugural address that “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem,” crystallizing the neoliberal view that state intervention often did more harm than good.42 This ideological stance translated into concrete policies, such as the dismantling of certain environmental regulations, the weakening of labor protections, and a dramatic reduction in antitrust enforcement. Agencies like the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice Antitrust Division adopted a more lenient approach to corporate consolidation, shifting the burden of proof to regulators and emphasizing economic efficiency over market structure.43

One of the most significant consequences of this shift was a redefinition of antitrust doctrine itself. Influenced by scholars from the Chicago School of Economics, particularly Robert Bork, antitrust enforcement during the Reagan era and beyond prioritized consumer welfare—primarily measured through prices—over concerns about market concentration or corporate power. Bork’s 1978 book, The Antitrust Paradox, became the intellectual foundation for this new approach, arguing that antitrust law had strayed from its purpose and needed to be recalibrated to avoid punishing firms simply for being large or efficient.44 As a result, mergers and acquisitions that would have raised red flags in previous decades were now routinely approved if there was no direct evidence that consumers would be harmed through higher prices. This narrow interpretation of antitrust law allowed corporations to grow significantly in size and scope, laying the groundwork for the megamergers of the 1990s and the emergence of corporate behemoths in the 21st century.

The neoliberal turn also had profound political and cultural implications. As markets were increasingly viewed as self-regulating and inherently just, public trust in government institutions declined, and the role of the state as a protector of economic fairness eroded. Labor unions, once a powerful counterweight to corporate influence, saw their membership and bargaining power diminish rapidly during this era. Meanwhile, financial deregulation opened the door to increased speculation, risky investment practices, and the concentration of wealth in the financial sector.45 While proponents of deregulation touted rising productivity and consumer choice, critics noted that these gains were unevenly distributed, contributing to growing income inequality, weakened labor protections, and reduced accountability for corporate malfeasance. The hollowing out of regulatory institutions made it increasingly difficult for the government to respond to corporate abuses, as was seen in the lead-up to the financial crisis of 2008.

Despite its critics, the neoliberal framework became deeply embedded in American economic policy across both Republican and Democratic administrations. Bill Clinton’s presidency, for example, embraced a form of “Third Way” neoliberalism, evident in policies such as the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act, the promotion of free trade agreements like NAFTA, and the continuation of relaxed antitrust enforcement.46 Clinton’s administration argued that globalization and deregulated markets were essential for U.S. competitiveness in the new economy, further blurring the line between center-left and center-right economic agendas. Even as economic inequality worsened and the social safety net came under increasing strain, neoliberalism retained its dominance in political discourse. It wasn’t until the 2008 financial crisis and the rise of new populist and progressive movements in the 2010s that serious challenges to neoliberal orthodoxy began to reemerge. Yet by that time, decades of deregulation had already profoundly reshaped the American corporate landscape and altered the public’s expectations of what government should or could do to regulate monopolies and protect the public interest.

21st-Century Tech Monopolies

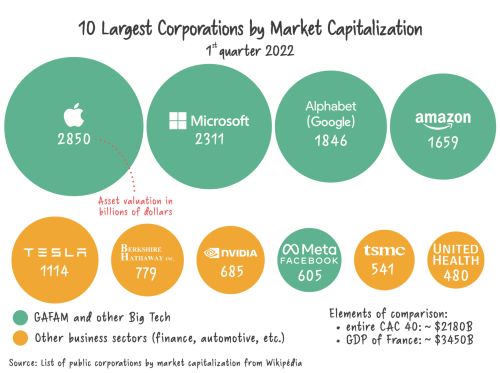

In the 2000s and 2010s, the monopoly conversation returned, this time focusing on Big Tech. Companies like Google, Amazon, Facebook (now Meta), Apple, and Microsoft came to dominate their respective markets.

In the 21st century, a new breed of monopolies has emerged, rooted not in traditional manufacturing or railroads but in the digital architecture of the modern economy. Companies like Google, Amazon, Apple, Meta (formerly Facebook), and Microsoft have come to dominate sectors ranging from search and e-commerce to mobile operating systems, cloud computing, and digital advertising. Unlike their industrial-era predecessors, these tech giants benefit from powerful network effects, in which the value of a service increases as more people use it. For example, the more users on Facebook, the more attractive it becomes to both users and advertisers, reinforcing its dominance and making it difficult for new competitors to gain a foothold. Similarly, Google’s dominance in search feeds directly into its supremacy in online advertising, as it collects massive amounts of user data to refine ad targeting.47 These network effects, compounded by high switching costs, data accumulation, and platform dependencies, enable tech monopolies to entrench themselves in ways that traditional antitrust tools struggle to address. As legal scholar Tim Wu argued, these companies have used their gatekeeping positions to control access to digital markets, often steering users, competitors, and even regulators toward outcomes that serve their interests.48

Moreover, many of these companies operate as multi-sided platforms—intermediaries between users and third-party vendors—giving them disproportionate leverage over entire ecosystems. Amazon, for example, not only hosts millions of third-party sellers but also competes directly with them through its private-label products, often using data from its own marketplace to undercut competitors.49 Apple similarly controls both the hardware and software environments of its devices, extracting a 30% commission from app developers via its App Store, a practice challenged in high-profile lawsuits like Epic Games v. Apple. While these behaviors echo classical monopolistic practices, their legal implications are murkier under the current consumer welfare framework, which tends to assess harm primarily through price effects. Many digital services are free at the point of use, complicating efforts to prove anticompetitive harm. Nonetheless, critics argue that these firms exhibit monopsony power—dominance over suppliers and labor markets—as well as political and cultural influence that rivals that of nation-states.50 Antitrust reformers, including the FTC under Chair Lina Khan, have begun rethinking regulatory approaches, emphasizing structural separations and platform neutrality. Still, addressing tech monopolies will require a fundamental reimagining of antitrust for the digital age, one that accounts for network-driven dominance, data asymmetries, and the societal costs of digital centralization.51

Conclusion

The history of monopolies in the United States is cyclical: from their explosive emergence in the Gilded Age, to Progressive-era regulation, to mid-century complacency, to the modern resurgence of corporate giants in new forms. What has remained consistent is the American public’s ambivalence—sometimes admiration, sometimes outrage—toward wealth and power concentrated in the hands of a few.

In an economy increasingly defined by information, automation, and data, the old debates about Standard Oil and railroads have evolved into questions about search engines, cloud computing, and digital privacy. Whether modern antitrust efforts will succeed in curbing these new monopolies remains to be seen, but history suggests that monopolistic dominance, when left unchecked, inevitably triggers a reaction. The American story of monopolies is, ultimately, a story of power—and the enduring struggle to ensure that power serves the many, not the few.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, ed. William Peden (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1955), 157–159; Richard R. John, Network Nation: Inventing American Telecommunications (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010), 34–36.

- Robert E. Wright, The Political Economy of the Early Republic: Essays on the Economic History of the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 45–48; John Lauritz Larson, Internal Improvement: National Public Works and the Promise of Popular Government in the Early United States (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 75–78.

- Alexander Hamilton, “Report on Manufactures,” in The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, ed. Harold C. Syrett, vol. 7 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961), 349–360; Ronald P. Formisano, The Transformation of Political Culture: Massachusetts Parties, 1790s–1840s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 22–26.

- Alfred D. Chandler Jr., The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1977), 12–15; Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (New York: W.W. Norton, 2005), 110–112.

- Charles W. McCurdy, The Anti-Monopoly Tradition and the Rise of the Progressives (New York: Columbia University Press, 1969), 5–10; Thomas K. McCraw, Prophets of Regulation (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984), 40–42.

- Ron Chernow, Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. (New York: Random House, 1998), 321–325; Matthew Josephson, The Robber Barons: The Classic Account of the Influential Capitalists Who Transformed America (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1934), 128–132.

- David Nasaw, Andrew Carnegie (New York: Penguin Press, 2006), 412–420; Chandler Jr., The Visible Hand, 95–102.

- McCurdy, The Anti-Monopoly Tradition and the Rise of the Progressives, 35-40; McCraw, Prophets of Regulation, 55–60.

- Chernow, Titan, 287-300; Josephson, The Robber Barons, 133-138.

- Robert H. Wiebe, The Search for Order, 1877–1920 (New York: Hill and Wang, 1967), 115–117; William L. Barney, The History of Standard Oil Company (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1905), 102–110.

- Ida M. Tarbell, The History of the Standard Oil Company (New York: McClure, Phillips & Co., 1904), 450–475; Alfred D. Chandler Jr., Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990), 205–210.

- Nasaw, Andrew Carnegie, 355-370; Chandler Jr., The Visible Hand, 115-120.

- Joseph F. Wallace, The Homestead Strike: Labor Conflict at the Carnegie Steel Company (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1990), 45–58; David Brody, Labor in Crisis: The Steel Strike of 1919 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1965), 12–18.

- Harold C. Livesay, Andrew Carnegie and the Rise of Big Business (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1980), 198–210; Richard R. John, American Business and Public Policy: The Changing Relationship (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990), 70–75.

- T.J. Stiles, The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009), 290–310; Maury Klein, The Life and Legend of Jay Gould (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986), 150–160.

- Richard White, Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2011), 205–215; H. Roger Grant, The Railroad and the American People (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012), 134–140.

- Jean Strouse, Morgan: American Financier (New York: Random House, 1999), 245–270; Harold C. Livesay, J.P. Morgan: Banker to a Growing Nation (New York: Columbia University Press, 1983), 182–200.

- Niall Ferguson, The House of Rothschild: Volume 2: The World’s Banker, 1849–1999 (New York: Penguin Press, 1998), 310–315; Charles W. Calomiris and Gary Gorton, The Origins of Banking Panics: Models, Facts, and Bank Regulation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 90–95.

- Robert F. Bruner and Sean D. Carr, The Panic of 1907: Lessons Learned from the Market’s Perfect Storm (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2007), 45–50; Allan M. Brandt, The Cigarette Century: The Rise, Fall, and Deadly Persistence of the Product That Defined America (New York: Basic Books, 2007), 36–48.

- Jonathan D. Moreno, The American Tobacco Industry and the Rise of Corporate Power (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), 112–125; McCraw, Prophets of Regulation, 92-97.

- Hans B. Thorelli, The Federal Antitrust Policy: Origination of an American Tradition (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1955), 227–230.

- William Letwin, Law and Economic Policy in America: The Evolution of the Sherman Antitrust Act (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965), 63–70.

- United States v. E.C. Knight Co., 156 U.S. 1 (1895).

- Marc Winerman, “The Origins of the FTC: Concentration, Cooperation, Control, and Competition,” Antitrust Law Journal 71, no. 1 (2003): 1–97.

- Edmund Morris, Theodore Rex (New York: Random House, 2001), 155–160.

- Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States (New York: Harper Perennial, 2003), 352–355.

- Gabriel Kolko, The Triumph of Conservatism: A Reinterpretation of American History, 1900–1916 (New York: Free Press, 1963), 98–102.

- Richard Hofstadter, The Age of Reform: From Bryan to F.D.R. (New York: Vintage Books, 1955), 144–148.

- Winerman, “The Origins of the FTC,” 33-36.

- Ellis W. Hawley, The New Deal and the Problem of Monopoly: A Study in Economic Ambivalence (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1966), 18–21.

- William E. Kovacic, “The Federal Trade Commission and Congressional Oversight of Antitrust Enforcement,” Tulane Law Review 72, no. 3 (1998): 659–663.

- Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., The Age of Roosevelt: The Coming of the New Deal (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1959), 102–106.

- Steve Coll, The Deal of the Century: The Breakup of AT&T (New York: Atheneum, 1986), 18–22.

- Gerald R. Faulhaber, “The AT&T Divestiture: Lessons Learned,” Federal Communications Law Journal 55, no. 1 (2002): 5–12.

- Thomas G. Krattenmaker, Telecommunications Law and Policy (Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 1998), 102–109.

- James W. Cortada, IBM: The Rise and Fall and Reinvention of a Global Icon (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019), 205–210.

- Richard J. Barber, “United States v. IBM: The Evidence, the Issues, and the Outcome,” Antitrust Law Journal 61, no. 2 (1993): 345–349.

- Steve Lohr, Go To: The Story of the Math Majors, Bridge Players, Engineers, Chess Wizards, Maverick Scientists and Iconoclasts — The Programmers Who Created the Software Revolution (New York: Basic Books, 2001), 156–160.

- William E. Kovacic and Carl Shapiro, “Antitrust Policy: A Century of Economic and Legal Thinking,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 14, no. 1 (2000): 43–45.

- Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (New York: Picador, 2007), 43–45.

- McCraw, Prophets of Regulation, 284-290.

- Ronald Reagan, “Inaugural Address,” January 20, 1981, in Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Ronald Reagan, 1981 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1982), 1.

- William E. Kovacic, “The Modern Evolution of U.S. Competition Policy Enforcement Norms,” Antitrust Law Journal 71, no. 2 (2003): 377–381.

- Robert H. Bork, The Antitrust Paradox: A Policy at War with Itself (New York: Basic Books, 1978), 7–11.

- David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 31–38.

- Elizabeth Warren, “The Coming Collapse of the Middle Class,” Speech at UC Berkeley, March 2007, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=akVL7QY0S8A.

- Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (New York: PublicAffairs, 2019), 85–91.

- Tim Wu, The Curse of Bigness: Antitrust in the New Gilded Age (New York: Columbia Global Reports, 2018), 47–52.

- Lina M. Khan, “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox,” Yale Law Journal 126, no. 3 (2017): 710–805.

- Zephyr Teachout, Break ‘Em Up: Recovering Our Freedom from Big Ag, Big Tech, and Big Money (New York: All Points Books, 2020), 132–136.

- Rebecca Allensworth, “The New Antitrust Federalism,” Vanderbilt Law Review 102, no. 4 (2020): 1399–1431.

Bibliography

- Allensworth, Rebecca. “The New Antitrust Federalism.” Vanderbilt Law Review 102, no. 4 (2020): 1399–1431.

- Barber, Richard J. “United States v. IBM: The Evidence, the Issues, and the Outcome.” Antitrust Law Journal 61, no. 2 (1993): 343–373.

- Barney, William L. The History of Standard Oil Company. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1905.

- Bork, Robert H. The Antitrust Paradox: A Policy at War with Itself. New York: Basic Books, 1978.

- Brandt, Allan M. The Cigarette Century: The Rise, Fall, and Deadly Persistence of the Product That Defined America. New York: Basic Books, 2007.

- Brody, David. Labor in Crisis: The Steel Strike of 1919. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1965.

- Bruner, Robert F., and Sean D. Carr. The Panic of 1907: Lessons Learned from the Market’s Perfect Storm. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2007.

- Calomiris, Charles W., and Gary Gorton. The Origins of Banking Panics: Models, Facts, and Bank Regulation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Chandler Jr., Alfred D. Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990.

- ———. The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1977.

- Chernow, Ron. Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr.. New York: Random House, 1998.

- Coll, Steve. The Deal of the Century: The Breakup of AT&T. New York: Atheneum, 1986.

- Cortada, James W. IBM: The Rise and Fall and Reinvention of a Global Icon. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2019.

- Faulhaber, Gerald R. “The AT&T Divestiture: Lessons Learned.” Federal Communications Law Journal 55, no. 1 (2002): 5–35.

- Ferguson, Niall. The House of Rothschild: Volume 2: The World’s Banker, 1849–1999. New York: Penguin Press, 1998.

- Formisano, Ronald P. The Transformation of Political Culture: Massachusetts Parties, 1790s–1840s. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983.

- Grant, H. Roger. The Railroad and the American People. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012.

- Hamilton, Alexander. “Report on Manufactures.” In The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, edited by Harold C. Syrett, vol. 7, 349–360. New York: Columbia University Press, 1961.

- Harvey, David. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Hawley, Ellis W. The New Deal and the Problem of Monopoly: A Study in Economic Ambivalence. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1966.

- Hofstadter, Richard. The Age of Reform: From Bryan to F.D.R.. New York: Vintage Books, 1955.

- Jefferson, Thomas. Notes on the State of Virginia, edited by William Peden. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1955.

- John, Richard R. American Business and Public Policy: The Changing Relationship. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990.

- ———. Network Nation: Inventing American Telecommunications. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Josephson, Matthew. The Robber Barons: The Classic Account of the Influential Capitalists Who Transformed America. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1934.

- Khan, Lina M. “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox.” Yale Law Journal 126, no. 3 (2017): 710–805.

- Klein, Maury. The Life and Legend of Jay Gould. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986.

- Klein, Naomi. The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. New York: Picador, 2007.

- Kolko, Gabriel. The Triumph of Conservatism: A Reinterpretation of American History, 1900–1916. New York: Free Press, 1963.

- Kovacic, William E. “The Federal Trade Commission and Congressional Oversight of Antitrust Enforcement.” Tulane Law Review 72, no. 3 (1998): 659–707.

- ———. “The Modern Evolution of U.S. Competition Policy Enforcement Norms.” Antitrust Law Journal 71, no. 2 (2003): 377–408.

- Kovacic, William E., and Carl Shapiro. “Antitrust Policy: A Century of Economic and Legal Thinking.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 14, no. 1 (2000): 43–60.

- Krattenmaker, Thomas G. Telecommunications Law and Policy. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 1998.

- Larson, John Lauritz. Internal Improvement: National Public Works and the Promise of Popular Government in the Early United States. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

- Letwin, William. Law and Economic Policy in America: The Evolution of the Sherman Antitrust Act. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965.

- Livesay, Harold C. Andrew Carnegie and the Rise of Big Business. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1980.

- ———. J.P. Morgan: Banker to a Growing Nation. New York: Columbia University Press, 1983.

- Lohr, Steve. Go To: The Story of the Math Majors, Bridge Players, Engineers, Chess Wizards, Maverick Scientists and Iconoclasts — The Programmers Who Created the Software Revolution. New York: Basic Books, 2001.

- McCraw, Thomas K. Prophets of Regulation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984.

- McCurdy, Charles W. The Anti-Monopoly Tradition and the Rise of the Progressives. New York: Columbia University Press, 1969.

- Moreno, Jonathan D. The American Tobacco Industry and the Rise of Corporate Power. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989.

- Morris, Edmund. Theodore Rex. New York: Random House, 2001.

- Nasaw, David. Andrew Carnegie. New York: Penguin Press, 2006.

- Reagan, Ronald. “Inaugural Address,” January 20, 1981. In Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Ronald Reagan, 1981. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1982.

- Schlesinger, Arthur M. Jr. The Age of Roosevelt: The Coming of the New Deal. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1959.

- Stiles, T.J. The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009.

- Strouse, Jean. Morgan: American Financier. New York: Random House, 1999.

- Tarbell, Ida M. The History of the Standard Oil Company. New York: McClure, Phillips & Co., 1904.

- Teachout, Zephyr. Break ‘Em Up: Recovering Our Freedom from Big Ag, Big Tech, and Big Money. New York: All Points Books, 2020.

- Thorelli, Hans B. The Federal Antitrust Policy: Origination of an American Tradition. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1955.

- United States Supreme Court. United States v. E.C. Knight Co., 156 U.S. 1 (1895).

- Wallace, Joseph F. The Homestead Strike: Labor Conflict at the Carnegie Steel Company. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1990.

- Warren, Elizabeth. “The Coming Collapse of the Middle Class.” Speech at UC Berkeley, March 2007. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=akVL7QY0S8A.

- White, Richard. Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2011.

- Wiebe, Robert H. The Search for Order, 1877–1920. New York: Hill and Wang, 1967.

- Wilentz, Sean. The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln. New York: W.W. Norton, 2005.

- Winerman, Marc. “The Origins of the FTC: Concentration, Cooperation, Control, and Competition.” Antitrust Law Journal 71, no. 1 (2003): 1–97.

- Wright, Robert E. The Political Economy of the Early Republic: Essays on the Economic History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Wu, Tim. The Curse of Bigness: Antitrust in the New Gilded Age. New York: Columbia Global Reports, 2018.

- Zinn, Howard. A People’s History of the United States. New York: Harper Perennial, 2003.

- Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. New York: PublicAffairs, 2019.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.17.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.