The paradox of proscription was that it cloaked illegality in the garments of law. Citizens were not murdered in defiance of the state; they were murdered by the state.

Originally published by Brewminate, 04.14.2024, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.

Introduction

In the tumultuous politics of the late Roman Republic and early Empire, few instruments embodied both the brutal pragmatism and the systemic fragility of the state more than the proscription. The proscription1 (literally, “a posting up” of names) was the public declaration that a citizen had been marked as an enemy of the res publica and placed outside the law. To appear on such a list was to suffer civic death: confiscation of property, loss of legal protection, and authorization for one’s killing with the promise of reward for the perpetrator. The practice struck at the heart of Roman notions of citizenship, which ideally conferred protection under the law and participation in the civic community. To be proscribed was not merely to be punished; it was to be erased.

The earliest and most infamous waves of proscription were conducted by Lucius Cornelius Sulla in 82 BCE, following his civil war victory. The precedent he set, legalizing murder and plunder under the guise of restoring order, was revived in even bloodier fashion by the Second Triumvirate in 43 BCE, when Marcus Antonius, Octavian, and Lepidus turned political purges into a mechanism for both vengeance and war financing. These episodes were not isolated aberrations. Rather, they revealed a structural weakness in the Republic: the weaponization of legality itself to serve factional ends. Even after Augustus claimed to have ended the age of proscriptions, the logic of declaring “enemies of the state” survived in subtler forms through treason trials (maiestas) and the symbolic penalties of damnatio memoriae.2

What follows argues that proscription was both a political weapon and a social rupture. It functioned as an expedient solution to crises of legitimacy, while at the same time eroding the very civic bonds upon which legitimacy rested. By tracing the practice from Sulla’s precedent, through the Triumviral carnage, to its transformation under the Julio-Claudians,3 we can better understand how the Republic’s internal violence facilitated its transformation into autocracy. The proscriptions illuminate the shifting boundaries of Roman citizenship,4 the tenuous balance between legality and force, and the enduring vulnerability of states when power is unmoored from consensus and vested instead in sanctioned elimination.

Origins and Legal Framework

Although the proscriptions of Sulla and the Triumvirs loom largest in Roman memory, the practice did not emerge ex nihilo.5 Roman political culture already contained mechanisms for excluding or declaring enemies. As early as the Republican struggles against internal insurrection and treason, the Senate could declare a citizen an hostis publicus (public enemy), which stripped him of civic protections and authorized his death without trial. This was an extraordinary weapon that rested less on codified statute than on the Senate’s authority to define political conflict as existential threat. The senatus consultum ultimum supplied a procedural framework that instructed magistrates to protect the state by any means necessary, even when ordinary safeguards were suspended.6

The proscriptio radicalized these earlier precedents. Instead of a temporary declaration against a specific rebel, proscription institutionalized exclusion in a public and bureaucratic way. Names were posted in the Forum, possessions were confiscated and auctioned, and rewards were offered to informers or assassins.7 In effect, proscription fused the Roman tradition of declaring an hostis with the older civic penalty of interdictio aquae et ignis (banishment), and then sharpened both into a mechanism of political terror.8

The symbolism of being named was central. Roman civic life depended on visibility, on recognition in courts, assemblies, and inscriptions. To have one’s name fixed to a tablet as an enemy inverted the meaning of civic record: the written word, usually a vehicle of honor and memory, became an instrument of erasure.9 As François Hinard emphasizes, proscription was not only a juridical procedure but also a ritualized act of exclusion that transformed private vendetta into public duty by mobilizing collective participation in killing.10

Sulla’s Proscriptions (82 BCE)

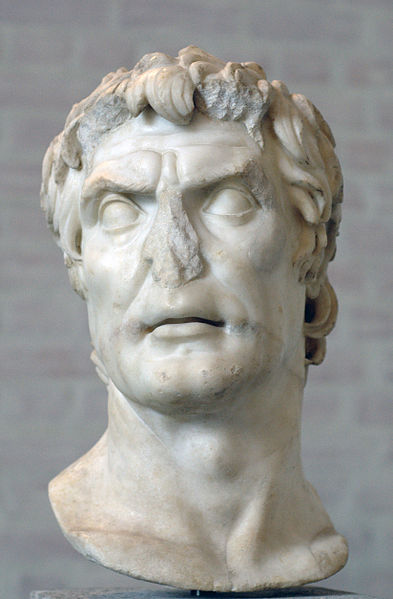

The first large-scale deployment of proscription in Roman history came under Lucius Cornelius Sulla, following his victory in the civil war of 83–82 BCE. Having marched on Rome twice and defeated the Marian faction at the Colline Gate, Sulla faced both the practical challenge of rewarding his veterans and the political need to eliminate opponents. His solution was the proscription list, a measure that fused political purging with economic redistribution.11

According to Appian, Sulla began by posting the names of eighty men, but within days the number swelled, ultimately reaching hundreds.12 Plutarch suggests that around 1,500 were executed in Rome and Italy, though precise figures remain uncertain.13 What is clear is the deliberate expansion of the lists, as enemies of varying political affiliations, personal rivals, and wealthy landholders were marked for elimination. The policy thus exceeded any narrow conception of justice: it was a program of terror and enrichment.

The mechanics were stark. Proscribed individuals were denied all legal recourse, their property confiscated and auctioned, often at bargain rates to Sulla’s supporters.14 Rewards were promised to anyone who killed a proscribed man or betrayed his hiding place, and penalties threatened for those who offered shelter. Families of the proscribed were disqualified from public office, ensuring the destruction of their political legacy.15

The consequences were profound. First, the proscriptions destabilized the senatorial aristocracy by eliminating old families and replacing them with novi homines who had profited from confiscations. Second, the moral authority of law itself was undermined: murder was not only permitted but legalized and rewarded.16 Third, the precedent ensured that future leaders would see mass political killing as a legitimate instrument of statecraft. As Arthur Keaveney has argued, Sulla’s proscription was not merely the product of personal cruelty but an institutionalized mechanism that permanently altered Roman politics.17

The Second Triumvirate’s Proscriptions (43 BCE)

If Sulla’s proscriptions shocked Rome, those of the Second Triumvirate terrified it anew. In 43 BCE, Marcus Antonius, Octavian, and Marcus Lepidus formed an alliance to avenge Julius Caesar’s assassination and secure their dominance over the state. Their compact was sealed not only in political agreements but in lists of enemies. As Appian vividly recounts, the Triumvirs each conceded the lives of personal friends to secure the deaths of their rivals.18 In this gruesome calculus, familial loyalty was subordinated to political expediency, and private vendetta merged with collective purge.

The scale of the Triumviral proscriptions dwarfed even Sulla’s. Ancient sources estimate that as many as 300 senators and 2,000 equites were proscribed.19 While these numbers may reflect rhetorical exaggeration, the breadth of the purge is undeniable. The infamous case of Cicero—hunted down and executed in December 43 BCE—became emblematic of the Republic’s demise. Plutarch and others emphasize that Cicero’s inclusion was a matter of personal vendetta by Antony, reluctantly accepted by Octavian in exchange for his own concessions.20

The mechanics of the lists largely followed Sullan precedent: posted names, legal outlawry, property confiscations, and rewards for informers. Yet there was a crucial addition. The Triumvirs used proscriptions explicitly as a means of financing war against Brutus and Cassius. The confiscated wealth of the proscribed was funneled into military expenditures, turning political killings into fiscal policy.21 This “monetization of death,” as François Hinard terms it, gave the proscriptions a new and chilling efficiency.

The social consequences were equally devastating. Once again, the aristocracy was decimated, and Roman elites learned that political fortune was precarious, dependent not on law but on proximity to power. Moreover, the alliance between Antony, Octavian, and Lepidus was cemented through the blood of shared enemies, yet also undermined by the moral stain of mass killing. As Cicero’s death demonstrated, the Republic’s last great voice for constitutionalism had been silenced, paving the way for autocracy.22

Imperial Adaptations: Julio-Claudian Uses of Proscription

With the rise of Augustus, the overt practice of proscription formally ceased. In his Res Gestae, Augustus claimed that he “spared all citizens who sought pardon,” a rhetorical contrast to the bloody precedent of the Triumvirate.23 Yet beneath this veneer of clemency, the logic of proscription, the marking of citizens as enemies and the removal of rivals through state sanction, remained embedded in imperial politics.

Instead of openly posting names, the Julio-Claudian dynasty adapted proscription into subtler forms of exclusion. One such adaptation was the treason trial (maiestas), which proliferated under Tiberius. What had begun as a legal category for betraying the Roman state expanded into an elastic charge that could encompass offensive speech, failed loyalty, or personal slights against the emperor.24 The accused, if convicted, faced confiscation of property and social obliteration, echoing the material and symbolic erasure of Republican proscriptions.

Caligula and Nero intensified these practices, transforming treason charges into tools of personal vendetta. In Tacitus’s Annals, the repeated theme is not justice but the emperor’s paranoia, driving prosecutions that enriched imperial coffers and silenced dissent.25 The victims of maiestas trials, like the proscribed before them, became examples to terrify the rest of the elite.

Another adaptation was damnatio memoriae, the official erasure of an individual from public commemoration. While not always accompanied by execution, it symbolically reproduced the same function as proscription: the obliteration of civic identity. Inscriptions were defaced, statues destroyed, names excised.26 Augustus himself had wielded similar symbolic gestures by casting Antony’s memory as treacherous, a moral rather than legal continuation of the Triumviral purge.

These imperial measures reveal the continuity of the proscription’s core logic. Though Augustus and his successors no longer nailed names in the Forum, the category of the “enemy of the state” endured, reshaped to fit a monarchy that sought to clothe repression in legality and ritual. As Barbara Levick observes, the Principate institutionalized the power to exclude while disguising it in procedures that appeared judicial rather than arbitrary.27

Social, Political, and Economic Consequences

The immediate effect of proscriptions, whether under Sulla or the Triumvirs, was the elimination of political opponents. But the deeper impact lay in the long-term transformation of Roman society. The redistribution of wealth and property was perhaps the most tangible consequence. Confiscated estates were sold at auction, often at discounted prices, to supporters of the ruling faction.28 This process not only enriched allies but also destabilized traditional aristocratic lineages. Families who had occupied the Senate for generations were extinguished or financially ruined, while novi homines, new men enriched by confiscations, rose rapidly in prominence.29

This reshaping of the Roman elite had lasting political implications. By creating new client networks dependent on their largesse, Sulla and later the Triumvirs bound economic survival to political loyalty. The effect was to erode the independence of the aristocracy and deepen the factionalization of Roman politics. As Andrew Lintott has argued, this linkage of violence to property rights undermined the very foundations of the Republic, in which wealth had once been a stabilizing factor in elite consensus.30

The psychological and cultural effects were no less significant. Proscription fostered a climate of fear and distrust, in which betrayal became a survival tactic. Neighbors denounced neighbors; freedmen betrayed patrons; even family members were tempted by the rewards offered for informing.31 The civic ideal of amicitial, the bonds of friendship and reciprocity, was shattered, replaced by suspicion. The Republic’s political culture, already fraying under the pressures of civil war, was corroded by the normalization of legalized murder.

The longer-term consequence was the delegitimization of Republican government itself. If citizenship could be revoked at a stroke, if law was manipulated to sanction violence, then the distinction between magistracy and tyranny collapsed. Cicero’s lament that “no house, no roof, no walls, no solitude could protect against treachery” speaks to the pervasive insecurity of the period.32 The Republic’s claim to provide civic security was fatally compromised, clearing the ideological ground for the Principate. In this sense, proscriptions were not only a symptom of crisis but a cause of systemic collapse.33

Comparative and Theoretical Perspectives

The Roman experience of proscription has often been invoked in later discussions of political violence. Its defining features (the formalization of outlawry, the public posting of names, the seizure of property, and the incentivization of betrayal) resonate with episodes of repression across history. François Hinard, in his seminal study, calls proscriptions “the institutionalization of terror.”34 They demonstrate how states can transform personal enmity into public duty, creating a machinery in which political elimination is not only permitted but mandated.

A useful comparative lens is the French Revolution’s Jacobin Terror (1793–94), during which lists of suspects were compiled, property confiscated, and executions framed as acts of civic purification.35 Like the Romans, the Jacobins fused legality with violence, using tribunals to cloak executions in the forms of law. Similarly, in the twentieth century, Stalin’s purges employed public denunciations and quotas of “enemies of the people,” echoing the Roman principle that the state’s survival justified the eradication of large segments of its own citizenry.36

These parallels highlight an enduring political pattern: the rhetoric of necessity legitimizes extraordinary violence. Once a community accepts that certain individuals are “enemies of the state,” the line between legality and murder dissolves. In Rome, the posting of names in the Forum symbolized this dissolution. In later contexts, newspapers, radio broadcasts, and modern media have served similar roles in broadcasting who may be targeted with impunity.

Theoretically, proscription raises fundamental questions about sovereignty. As Carl Schmitt famously argued, the sovereign is he who decides on the exception, the suspension of normal law in the name of preserving order.37 The Roman proscriptions embody this principle: legality itself was repurposed to suspend the protections of citizenship. What results is a paradox: violence is legalized, but in legalizing violence, law is emptied of its restraining function.

Thus, while uniquely Roman in form, proscriptions represent a recurring phenomenon in the history of political repression. They illustrate the vulnerability of any system, republican or otherwise, when emergency powers become instruments of factional or personal survival.

Conclusion

The Roman practice of proscription was at once a tool of immediate political survival and a mechanism that corroded the foundations of the Republic. Beginning with Sulla, who institutionalized outlawry on an unprecedented scale, through the Second Triumvirate’s even broader purge, and into the subtler adaptations of the Julio-Claudian emperors, proscription reveals how legality could be weaponized to sanctify violence. Its impact was not confined to the elimination of rivals. It reshaped aristocratic society through the redistribution of property, sowed distrust within the civic body, and habituated Romans to the idea that politics could legitimately be conducted through sanctioned killing.38

The paradox of proscription was that it cloaked illegality in the garments of law. Citizens were not murdered in defiance of the state; they were murdered by the state, in accordance with decrees and lists posted in the Forum. The practice demonstrates the fragility of republican forms when civic trust is undermined and when legality itself becomes the instrument of factional dominance. As Cicero’s fate shows, even the most prominent defenders of the Republic could be rendered enemies by decree.39

In broader historical perspective, the Roman proscriptions anticipate later episodes of political purging, from revolutionary France to twentieth-century totalitarian regimes. The enduring lesson is stark: when law is transformed into a tool for exclusion and elimination, the civic community ceases to function as a body of citizens and becomes instead a hierarchy of survival. Rome’s descent into autocracy cannot be understood apart from this phenomenon. Proscription was both a symptom of the Republic’s crisis and one of the decisive forces that brought it to an end.40

Appendix

Footnotes

- Appian, The Civil Wars 1.95–104.

- Plutarch, Life of Sulla 31–32.

- Cicero, Philippics 2.67; see also Catherine Steel, Cicero, Rhetoric and Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 113–15.

- François Hinard, Les proscriptions de la Rome républicaine (Rome: École Française de Rome, 1985), 45–47.

- Harriet I. Flower, Roman Republics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 150–54.

- Andrew Lintott, The Constitution of the Roman Republic (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 90–92.

- Appian, Civil Wars 1.95–96.

- W. Lintott, “The Quaestiones Perpetuae,” in The Cambridge Ancient History, 2nd ed., vol. 9, The Last Age of the Roman Republic, 146–43 B.C., ed. J. A. Crook, Andrew Lintott, and Elizabeth Rawson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 76–77.

- Harriet I. Flower, Roman Republics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 148.

- François Hinard, Les proscriptions de la Rome républicaine (Rome: École Française de Rome, 1985), 31–35.

- Arthur Keaveney, Sulla: The Last Republican (London: Routledge, 1982), 117–18.

- Appian, Civil Wars 1.95–103.

- Plutarch, Life of Sulla 31–32.

- Cicero, De Officiis 2.7; see also Andrew Lintott, Violence in Republican Rome (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999), 116–17.

- Appian, Civil Wars 1.96; François Hinard, Les proscriptions de la Rome républicaine (Rome: École Française de Rome, 1985), 65–67.

- Harriet I. Flower, Roman Republics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 151.

- Keaveney, Sulla, 121–22.

- Appian, Civil Wars 4.5–6.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History 47.6; Appian, Civil Wars 4.5.

- Plutarch, Life of Cicero 46–48.

- Hinard, Les proscriptions de la Rome républicaine, 145–50.

- Catherine Steel, Cicero, Rhetoric and Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 183–85.

- Augustus, Res Gestae Divi Augusti 2; see also Alison Cooley, Res Gestae Divi Augusti: Text, Translation, and Commentary (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 39–40.

- R. A. Bauman, The Crimen Maiestatis in the Roman Republic and the Augustan Principate (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1967), 80–84.

- Tacitus, Annals 1.72; 6.7.

- Harriet I. Flower, The Art of Forgetting: Disgrace and Oblivion in Roman Political Culture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 105–10.

- Barbara Levick, Tiberius the Politician (London: Routledge, 1976), 163–65.

- Appian, Civil Wars 1.96; 4.5.

- Plutarch, Life of Sulla 31; Harriet I. Flower, Roman Republics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 152.

- Andrew Lintott, Violence in Republican Rome (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999), 118–20.

- François Hinard, Les proscriptions de la Rome républicaine (Rome: École Française de Rome, 1985), 201–3.

- Cicero, Philippics 2.67.

- David Shotter, The Fall of the Roman Republic (London: Routledge, 2005), 89–92.

- François Hinard, Les proscriptions de la Rome républicaine (Rome: École Française de Rome, 1985), 9.

- Timothy Tackett, The Coming of the Terror in the French Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015), 210–14.

- Robert Conquest, The Great Terror: A Reassessment (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990), 77–82.

- Carl Schmitt, Political Theology, trans. George Schwab (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 5–7.

- David Shotter, The Fall of the Roman Republic (London: Routledge, 2005), 94.

- Plutarch, Life of Cicero 47.

- Harriet I. Flower, Roman Republics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 154.

Bibliography

- Appian. The Civil Wars. Translated by John Carter. London: Penguin, 1996.

- Augustus. Res Gestae Divi Augusti. In Cooley, Alison. Res Gestae Divi Augusti: Text, Translation, and Commentary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Bauman, R. A. The Crimen Maiestatis in the Roman Republic and the Augustan Principate. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1967.

- Cassius Dio. Roman History. Translated by Earnest Cary. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1914–27.

- Cicero. De Officiis. Translated by Walter Miller. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1913.

- Cicero. Philippics. Translated by D. R. Shackleton Bailey. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009.

- Conquest, Robert. The Great Terror: A Reassessment. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Flower, Harriet I. Roman Republics. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

- Flower, Harriet I. The Art of Forgetting: Disgrace and Oblivion in Roman Political Culture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

- Hinard, François. Les proscriptions de la Rome républicaine. Rome: École Française de Rome, 1985.

- Keaveney, Arthur. Sulla: The Last Republican. London: Routledge, 1982.

- Levick, Barbara. Tiberius the Politician. London: Routledge, 1976.

- Lintott, Andrew. The Constitution of the Roman Republic. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Lintott, Andrew. Violence in Republican Rome. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1999.

- Lintott, A. W. “The Quaestiones Perpetuae.” In The Cambridge Ancient History, 2nd ed., vol. 9, The Last Age of the Roman Republic, 146–43 B.C., edited by J. A. Crook, Andrew Lintott, and Elizabeth Rawson, 74–102. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Plutarch. Lives. Translated by Bernadotte Perrin. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1914.

- Schmitt, Carl. Political Theology. Translated by George Schwab. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- Shotter, David. The Fall of the Roman Republic. London: Routledge, 2005.

- Steel, Catherine. Cicero, Rhetoric and Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Tacitus. Annals. Translated by A. J. Woodman. Indianapolis: Hackett, 2004.

- Tackett, Timothy. The Coming of the Terror in the French Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.06.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.