The history of Big Tobacco demonstrates that denial was never merely rhetorical improvisation in the face of crisis. It was structurally integrated.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Denial, Doubt, and the Public Narrative

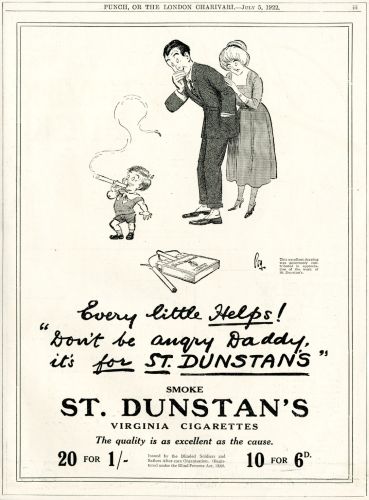

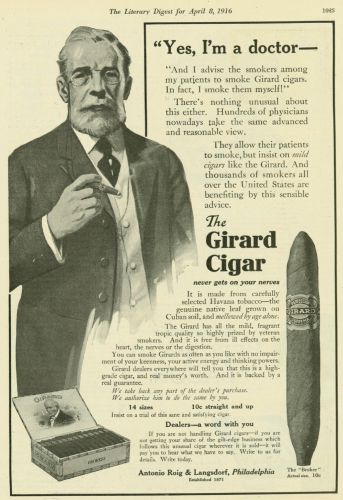

For much of the twentieth century, the American tobacco industry publicly framed cigarette consumption as a matter of personal choice rather than engineered dependency. Smoking was presented as a lifestyle preference, a symbol of sophistication, independence, relaxation, and even modern identity. Advertising campaigns associated cigarettes with physicians, athletes, film stars, and soldiers, embedding the product within narratives of trustworthiness and patriotism. Print ads and televised commercials rarely addressed health concerns directly; instead, they normalized daily use as an ordinary and even desirable component of adult life. Corporate statements emphasized consumer freedom, market competition, and individual responsibility, reinforcing the idea that smoking was a voluntary act undertaken by informed adults. As scientific research increasingly linked smoking to lung cancer and cardiovascular disease, tobacco executives insisted that causation remained uncertain and that alternative explanations warranted continued debate. The dominant narrative positioned consumers as autonomous actors exercising rational judgment in a marketplace of lawful products. By foregrounding choice and minimizing structural influence, the industry cultivated a moral framework in which continued smoking appeared to be a personal decision rather than the outcome of deliberate product engineering.

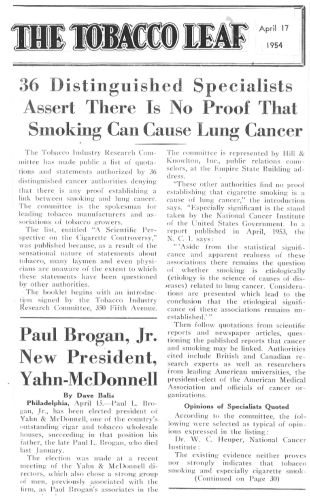

This rhetoric of choice was reinforced by a systematic cultivation of doubt. Following the landmark 1964 Report of the Surgeon General, which concluded that cigarette smoking was causally related to lung cancer in men and associated with other serious diseases, tobacco companies did not concede the point. Instead, they amplified claims of scientific controversy. Industry-funded research initiatives emphasized ambiguity, alternative explanations, and methodological limitations. Public statements stressed that the science was unsettled, encouraging consumers to interpret warnings as provisional rather than definitive. Doubt functioned as strategy, extending the life of a profitable product by reframing risk as debate.

Within this public narrative, addiction was either denied outright or recharacterized as habit. Corporate leaders testified before Congress that nicotine was not addictive in the pharmacological sense, maintaining that smokers could quit if sufficiently motivated. The language of habit preserved the logic of personal responsibility. If smoking persisted, it was because individuals chose to continue, not because products were designed to foster dependence. This framing insulated corporations from moral and legal accountability by displacing causation onto consumer behavior. The emphasis on voluntary choice obscured the structural features of cigarette design that enhanced nicotine delivery and reinforced repeated consumption.

The eventual release of internal tobacco industry documents would expose a stark divergence between public rhetoric and private knowledge. Corporate memoranda revealed that nicotine’s addictive properties were well understood and actively studied decades before public admission. Strategies to calibrate nicotine levels and sustain long-term use were discussed as business imperatives. The gap between external denial and internal recognition reframed the historical debate. What had been presented as uncertainty and individual choice emerged as coordinated narrative management. Denial and doubt were not defensive reactions to incomplete science; they were integral components of a broader architecture designed to preserve consumption and delay accountability.

Nicotine as Design Variable: The Engineering of Addiction

As public controversy intensified in the mid-twentieth century, internal tobacco research increasingly treated nicotine not as a fixed property of tobacco leaf but as a controllable design variable central to corporate survival. Far from viewing addiction as incidental, company scientists and executives analyzed nicotine delivery as foundational to long-term market stability and revenue predictability. Internal memoranda described cigarettes explicitly as “nicotine delivery devices,” underscoring the recognition that consumer loyalty depended upon sustaining pharmacological satisfaction rather than merely brand imagery. Research divisions monitored nicotine absorption rates, smoker behavior, and patterns of quitting, integrating chemical knowledge with marketing strategy. The chemical composition of smoke, the speed at which nicotine reached the bloodstream, and the sensory experience of inhalation became subjects of deliberate experimentation. Addiction, in this framework, was not a regrettable side effect of tobacco consumption but the economic engine that ensured repeat purchase behavior. Product design was inseparable from profit logic, and nicotine was calibrated accordingly.

Nicotine levels could be manipulated through blending practices and agricultural selection. Companies experimented with different tobacco strains and curing processes to optimize nicotine yield. More significantly, technological adjustments to cigarette construction altered how nicotine was delivered to the bloodstream. The addition of ammonia compounds, for example, increased the alkalinity of smoke and facilitated faster absorption of free-base nicotine. This engineering intensified the drug’s impact while preserving the appearance of conventional cigarette design. Product modification was calibrated to sustain dependency even as public discourse emphasized moderation and choice.

Flavoring agents and chemical additives further refined the experience of consumption, particularly in ways that expanded the consumer base. Harshness, throat irritation, and unpleasant taste could discourage new smokers, especially adolescents and first-time users who lacked tolerance for strong smoke. Internal research identified methods to smooth inhalation and mask bitterness, lowering the sensory barrier to initiation. Menthol and other additives made cigarettes more palatable and easier to inhale deeply, enhancing nicotine delivery while diminishing immediate discomfort. Such refinements were not merely aesthetic adjustments but strategic interventions designed to increase the likelihood of continued use after experimentation. By modifying flavor and texture, companies aligned product chemistry with behavioral objectives: ease of entry, rapid reinforcement, and long-term maintenance of consumption. The cigarette became a technologically managed object in which chemistry and marketing converged to embed addiction within ordinary use.

Light and low-tar cigarettes illustrate another dimension of engineered design. As health concerns mounted, companies marketed filtered and “light” brands as safer alternatives. Yet internal testing revealed that smokers compensated by inhaling more deeply or smoking more cigarettes to maintain nicotine intake. Ventilation holes in filters diluted machine-measured tar but did not meaningfully reduce exposure for human users. Product architecture preserved addictive potential while cultivating an illusion of reduced risk. The appearance of reform coexisted with maintenance of dependency.

Internal documents demonstrate that corporate knowledge of nicotine’s addictive properties preceded public acknowledgment by decades. Research divisions studied pharmacological mechanisms and consumer behavior, correlating nicotine yield with brand loyalty and cessation rates. Executives discussed the importance of retaining “replacement smokers” to offset mortality and quitting. Such language underscores the centrality of addiction to long-term profitability. The sustained investment in chemical manipulation and product refinement cannot be reconciled with public claims that smoking was merely habit or preference.

By treating nicotine as a manipulable design variable, the tobacco industry embedded dependency within the architecture of its product in a manner that extended beyond chemistry alone. The cigarette was not simply a rolled tobacco leaf but a technologically calibrated device optimized for initiation, reinforcement, and sustained use. Engineering decisions influenced how easily smoke could be inhaled, how quickly nicotine reached the brain, and how reliably cravings would return. These decisions were informed by internal knowledge of pharmacology and consumer behavior, revealing a systematic alignment between product design and addictive outcome. When later litigation exposed these practices, the legal implications were substantial: harm could no longer be attributed solely to consumer choice or ignorance. It was traceable to deliberate design strategies supported by internal research and corporate awareness. In this light, addiction emerged not as an unintended byproduct of tobacco consumption but as an engineered outcome embedded in product architecture and maintained through calculated innovation.

Youth as Market Strategy: Targeting the Malleable Consumer

As internal research clarified the centrality of addiction to profitability, tobacco executives increasingly recognized that long-term revenue depended upon early initiation. Company memoranda referred to adolescents as “replacement smokers,” a term that acknowledged the inevitability of attrition through illness, cessation, and death among older consumers. Market stability required continuous recruitment to sustain sales volumes over decades. Youth were not incidental participants in cigarette consumption but structurally necessary to its perpetuation within a declining adult population. Initiation during adolescence dramatically increased the likelihood of sustained use into adulthood, ensuring durable brand loyalty and extended purchasing life cycles. Internal analyses tracked the age at which smokers first experimented and correlated earlier initiation with stronger dependence and lower cessation rates. The strategic importance of young consumers became embedded in corporate planning, aligning product development and promotional strategies with the goal of capturing loyalty before competing influences could intervene.

Advertising campaigns reflected this orientation in both imagery and placement. Promotional materials emphasized independence, rebellion, athleticism, attractiveness, and social belonging, themes particularly resonant with adolescent identity formation. Campaigns associated smoking with maturity and autonomy, subtly framing cigarette use as a marker of transition into adulthood. Cartoon mascots such as Joe Camel blurred the line between adult product and youth-friendly branding, generating widespread recognition among children and teenagers and normalizing cigarette imagery in youth culture. Promotional events, sponsorships, and point-of-sale displays were positioned to maximize visibility in convenience stores, sporting venues, and media environments frequented by younger audiences. While companies publicly denied targeting minors and maintained that advertising was directed at existing adult smokers, internal marketing research frequently analyzed youth smoking patterns, brand recognition, and susceptibility to promotional themes. The architecture of promotion aligned product visibility with the psychological vulnerabilities of adolescence, leveraging aspiration and peer identification to facilitate early experimentation.

Product design complemented marketing strategy. Flavorings such as menthol reduced harshness and facilitated inhalation among new smokers. Slim and flavored varieties were tailored to specific demographic segments, including young women. Packaging aesthetics and brand identity cultivated aspirational associations that extended beyond nicotine’s pharmacological effects. The ease of initiation was not merely a marketing achievement but a design objective. Lowering sensory barriers increased the probability that experimentation would transition into regular use. In this convergence of product modification and targeted messaging, youth emerged as a central focus of corporate strategy.

Legal proceedings in the late twentieth century increasingly scrutinized this alignment between marketing and vulnerability. Evidence presented in litigation demonstrated that companies understood the relationship between early initiation and lifelong addiction. Courts and regulatory bodies concluded that youth were not accidental consumers but foreseeable and intended participants in the cigarette market. This recognition marked a critical expansion of corporate accountability. By identifying deliberate targeting of malleable populations, legal reasoning connected internal knowledge with public harm. The exploitation of youthful vulnerability was reframed not as incidental oversight but as integral to the architecture of addiction.

Internal Knowledge and Suppressed Evidence

The public narrative of uncertainty surrounding smoking’s health risks was increasingly at odds with the tobacco industry’s internal research by the mid-twentieth century. Corporate laboratories conducted extensive studies on nicotine pharmacology, carcinogenic compounds in smoke, patterns of inhalation, and consumer dependency. Internal memoranda and research summaries acknowledged that nicotine exerted physiological effects consistent with addiction, including reinforcement mechanisms and withdrawal symptoms, even as executives publicly denied such conclusions. Scientists within company research divisions analyzed absorption rates, behavioral conditioning, and the neurological effects of repeated exposure. This divergence between private recognition and public denial was not incidental or momentary. It reflected a sustained strategy to manage risk perception while preserving profitability. Internal documentation demonstrates that corporate leadership understood both the addictive properties of nicotine and the mounting epidemiological evidence linking smoking to cancer, heart disease, and respiratory illness. Rather than disclose these findings transparently, companies calibrated their public messaging to emphasize uncertainty, thereby insulating themselves from regulatory and legal consequences.

Research findings that threatened sales were often compartmentalized or reinterpreted. Rather than publicly conceding risk, companies funded alternative studies designed to emphasize ambiguity or methodological limitations. Scientific consultants were retained to question causation and highlight confounding variables. Industry organizations created to appear independent served as vehicles for disseminating counter-narratives. The goal was not necessarily to disprove the health consequences of smoking but to prolong uncertainty. Delay functioned as protection. As long as controversy could be sustained, regulation could be postponed and consumer behavior maintained.

Internal communications reveal awareness of the legal implications of addiction research. Memoranda advised caution in phrasing and documentation, recognizing that written acknowledgment of nicotine’s addictive properties could expose companies to liability. Some research initiatives were structured to minimize discoverability, and sensitive findings were shielded within corporate hierarchies. This pattern suggests not mere oversight but calculated management of information. The architecture of suppression paralleled the architecture of addiction: both were designed to stabilize revenue by controlling knowledge.

The release of millions of internal documents during the Minnesota Tobacco Trial in the 1990s exposed this concealed landscape to public scrutiny. Emails, research reports, strategic memoranda, and marketing analyses revealed sustained awareness of addiction and deliberate efforts to shape public understanding. Executives discussed nicotine dependence as a business asset while publicly denying its addictive nature. Internal conversations acknowledged the importance of youth initiation, even as advertising campaigns avoided overt references to minors. These documents contradicted decades of sworn testimony and promotional claims. Courts, journalists, and policymakers could now compare external statements with internal deliberations, revealing patterns of deception and strategic omission. The evidentiary weight of this material transformed the legal terrain, shifting debates from abstract accusations to documented proof of knowledge, concealment, and coordinated messaging.

The exposure of suppressed evidence marked a decisive moment in the reconfiguration of corporate accountability. Addiction and disease were no longer framed solely as outcomes of consumer misjudgment or unfortunate risk-taking. They were connected to documented internal awareness and strategic obfuscation that extended across decades. The tobacco industry’s handling of scientific knowledge demonstrated how institutional design can encompass not only product engineering but also information management and narrative control. Suppression became part of the broader architecture sustaining dependency and delaying reform. In revealing the sustained gap between private knowledge and public narrative, litigation reframed responsibility in terms that incorporated deliberate design, intentional youth targeting, and calculated concealment. The recognition that harm was foreseeable and internally acknowledged fundamentally altered the moral and legal evaluation of corporate conduct.

The Architecture of Doubt: Scientific Manipulation and Delay

Beyond product engineering and internal suppression, the tobacco industry constructed an external architecture of doubt designed to influence public perception, scientific discourse, and regulatory response over decades. Rather than directly refute mounting epidemiological evidence linking smoking to cancer and cardiovascular disease, companies adopted a strategy of amplification: emphasizing uncertainty wherever possible. Public relations campaigns framed smoking-related disease as a matter of ongoing scientific debate rather than established fact, even after major medical bodies reached consensus. Corporate statements highlighted complexity, statistical variability, and the need for “more research,” positioning the industry as responsible and methodical rather than defensive. By insisting that science was incomplete, executives cultivated the impression that regulatory action would be premature and potentially unjust. This posture allowed companies to continue marketing aggressively while appearing engaged in good-faith inquiry. Doubt was not merely rhetorical; it was institutionalized as a strategic resource deployed to slow the translation of scientific findings into public policy.

Industry-funded research organizations played a central role in this strategy. Bodies such as the Tobacco Industry Research Committee were established to sponsor studies that emphasized alternative explanations for rising cancer rates, including genetic predisposition, air pollution, or lifestyle variables. Funding frequently flowed toward projects unlikely to produce definitive conclusions, thereby sustaining ambiguity rather than resolving it. Corporate executives understood that the mere existence of ongoing research could be invoked as evidence that questions remained unsettled. The objective was not necessarily to generate conclusive counter-evidence but to maintain the perception of controversy within media and legislative arenas. By selectively promoting findings that minimized risk and downplaying those that confirmed harm, the industry shaped the informational environment encountered by consumers and policymakers alike. The cultivation of scientific plurality functioned as a protective buffer, shielding corporate practices from swift regulatory intervention and reinforcing the narrative of uncertainty.

Lobbying efforts reinforced this architecture. Tobacco companies invested heavily in influencing legislators and regulatory agencies, emphasizing the economic importance of the industry and the potential costs of stringent controls. Campaign contributions and coordinated messaging ensured that policymakers encountered persistent arguments about personal responsibility and market freedom. By intertwining economic impact with scientific uncertainty, the industry complicated regulatory momentum. Delay became strategy. Each additional year of uncertainty translated into sustained revenue and continued recruitment of new consumers.

The manipulation of doubt extended into media strategy. Advertisements and public statements often juxtaposed warnings with reassurances, suggesting that risks were exaggerated or statistically marginal. Corporate spokespersons appeared in televised hearings and interviews to question methodological standards or highlight dissenting experts. The repetition of doubt across platforms normalized skepticism. Consumers confronted not a clear narrative of risk but a contested terrain in which conclusions appeared unsettled. This environment of ambiguity dampened urgency and diffused accountability.

The architecture of doubt operated as a structural complement to the engineering of addiction. While product design secured dependency at the level of chemistry and behavior, public narrative management secured time at the level of regulation and litigation. By cultivating uncertainty and leveraging institutional inertia, tobacco companies postponed regulatory intervention and legal liability for decades, preserving profits while harm accumulated. The deliberate synchronization of scientific manipulation, media messaging, and political lobbying demonstrates that doubt was not accidental byproduct but coordinated strategy. The eventual unraveling of this architecture through litigation and document disclosure revealed that delay had been purposeful rather than incidental. In exposing the strategic manufacture of doubt, courts and regulators recognized that manipulation of scientific discourse itself constituted part of the broader institutional design sustaining harm and obstructing accountability.

Legal Reckoning: From Personal Choice to Corporate Design

The legal reckoning that emerged in the 1990s and early twenty-first century marked a decisive break with decades of deference to the rhetoric of personal choice. For much of the twentieth century, litigation against tobacco companies faltered on the argument that smokers assumed known risks when they chose to purchase and consume cigarettes. Defense attorneys emphasized warning labels, public health campaigns, and the widespread cultural normalization of smoking as evidence that consumers acted voluntarily. The framing of addiction as habit reinforced this argument, suggesting that cessation depended on willpower rather than chemical manipulation. Courts often accepted this reasoning, viewing tobacco as a lawful product used by informed adults. However, the release of internal industry documents fundamentally altered the evidentiary landscape. Plaintiffs and state attorneys general could now demonstrate not only knowledge of health risks but deliberate manipulation of nicotine delivery, coordinated misinformation campaigns, and strategic targeting of youth. The legal focus shifted from consumer autonomy to corporate design and deception. What had once been characterized as individual misjudgment increasingly appeared as the predictable outcome of engineered dependency and concealed knowledge.

The 1998 Master Settlement Agreement between major tobacco companies and forty-six states institutionalized this transformation. The agreement imposed substantial financial penalties, restricted certain advertising practices, and funded public health initiatives. More importantly, it acknowledged that the industry’s conduct extended beyond ordinary commercial activity. Marketing practices directed at youth were curtailed, and internal documents were made publicly accessible. The settlement did not eliminate smoking or dissolve tobacco corporations, but it represented formal recognition that harm had been facilitated by corporate strategy rather than solely by consumer decision.

Federal litigation further consolidated this shift. In United States v. Philip Morris USA Inc. (2006), the Department of Justice successfully argued that tobacco companies had engaged in a decades-long scheme to deceive the public about the health risks and addictiveness of cigarettes. The court concluded that the industry had violated federal racketeering statutes by coordinating misinformation campaigns and suppressing evidence. Judicial findings emphasized that addiction was not an unforeseen outcome but a foreseeable and intended result of product design and marketing practices. By centering internal knowledge and deliberate conduct, the ruling reframed accountability in structural terms.

The legal reckoning transformed the conceptual vocabulary of responsibility in American corporate law. Cigarette consumption could no longer be understood purely as an exercise of personal freedom detached from corporate influence. Courts and policymakers recognized that product architecture, marketing strategy, and information management formed an integrated system sustaining addiction over generations. Responsibility expanded beyond isolated acts of false advertising to encompass the coordinated design of products and narratives that fostered dependency while obscuring risk. This shift did not eliminate debates over personal agency, but it recalibrated the balance between consumer choice and corporate accountability. By acknowledging engineered addiction and deliberate delay, late twentieth-century litigation established a precedent for evaluating harm through the lens of institutional design rather than individual intent alone. In doing so, it reshaped not only tobacco regulation but broader understandings of how corporate structures can generate foreseeable injury.

Conceptual Shift: Addiction as Engineered Outcome

The cumulative exposure of internal documents, scientific manipulation, youth targeting, and coordinated denial produced a conceptual transformation in how addiction itself was understood. For decades, public discourse framed smoking as a risky but voluntary habit, sustained by personal weakness or social influence. The emerging legal and historical record disrupted this framing by demonstrating that dependency had been anticipated, studied, and cultivated within corporate research divisions. Addiction ceased to appear as an unfortunate side effect of consumer behavior and emerged instead as a predictable result of deliberate design. This shift reoriented moral and legal analysis from the psychology of the smoker to the architecture of the product.

Important to this transformation was the recognition that nicotine delivery could be engineered to optimize reinforcement with remarkable precision. The cigarette became visible not as a simple agricultural commodity but as a technologically refined device engineered to manage dosage, speed, and sensory impact. Chemical additives, filter ventilation, flavor modification, paper porosity, and calibrated nicotine absorption formed an integrated system structured to sustain craving and minimize barriers to repeated use. Internal research analyzed how rapidly nicotine reached the brain, how sensory smoothness influenced inhalation depth, and how product variation could maintain brand loyalty across demographic groups. The addictive outcome was not incidental to product success; it was embedded within a coordinated set of design decisions shaped by pharmacological knowledge. In this light, repeated consumption reflected not merely individual inclination but structured biochemical reinforcement intentionally engineered to sustain dependence. The locus of responsibility accordingly migrated from the willpower of the smoker to the deliberate strategies of the manufacturer.

The exposure of internal knowledge further solidified this shift by demonstrating alignment between scientific awareness and corporate strategy. When courts and scholars documented that executives understood addiction as essential to long-term profitability, the narrative of uncertainty collapsed under documentary evidence. Internal correspondence revealed acknowledgment that nicotine was the primary reason consumers continued smoking, even as public statements avoided such admissions. Research divisions tracked addiction metrics and discussed the maintenance of “replacement smokers” as necessary to offset cessation and mortality. The internal articulation of nicotine as indispensable to market survival undercut public claims that smoking was simply a matter of taste or adult preference. Addiction became legible as intended effect rather than accidental correlation. The coherence between product architecture, youth marketing, and scientific suppression revealed systematic coordination rather than fragmented oversight. This documentary alignment provided the evidentiary foundation for reclassifying smoking-related harm as the foreseeable outcome of intentional institutional design.

The broader implication extended beyond tobacco. By establishing that corporate actors could deliberately structure products to cultivate dependency while publicly denying it, litigation reframed the meaning of accountability in modern markets. Addiction was no longer solely a medical or behavioral phenomenon; it was a design outcome capable of legal evaluation. The recognition that harm can be embedded within architecture expanded regulatory logic to consider foreseeability, internal awareness, and intentional calibration. Corporate responsibility now encompassed not only overt misrepresentation but also the structured creation of dependency.

The conceptual shift from addiction as habit to addiction as engineered outcome marked a pivotal moment in late twentieth-century regulatory thought and corporate jurisprudence. It redefined the boundaries between consumer autonomy and corporate power, emphasizing that choices are shaped within environments structured by design rather than exercised in isolation. By situating dependency within product architecture, courts and scholars illuminated the mechanisms through which institutional systems can manufacture predictable harm while maintaining the façade of individual freedom. This reframing altered not only tobacco regulation but broader debates about pharmaceuticals, food systems, and digital platforms, where questions of engineered engagement and dependency increasingly arise. The tobacco litigation era crystallized a principle with enduring relevance: when dependency is deliberately constructed, internally understood, and economically incentivized, responsibility attaches not merely to consumption but to the architecture that makes such consumption persistently probable.

Enduring Legacies: Product Architecture and Modern Corporate Accountability

The tobacco litigation era did not simply regulate a single industry; it reshaped the grammar through which courts, regulators, and scholars evaluate corporate responsibility. By demonstrating that addiction could be engineered, internally studied, and publicly denied, the tobacco cases established a model for interrogating product architecture rather than merely consumer conduct. This legacy persists in contemporary debates over pharmaceuticals, processed foods, digital platforms, and other industries where dependency and behavioral conditioning are implicated. The conceptual apparatus forged in tobacco litigation provides a framework for examining whether harm is incidental or embedded within design.

In pharmaceutical regulation, scrutiny increasingly extends beyond labeling and warnings to the structure of dosage systems, marketing practices, and distribution channels. The opioid crisis prompted examination of how promotional strategies, risk minimization campaigns, and formulation decisions contributed to widespread dependency. Investigations focused not only on what companies claimed publicly but also on internal assessments of addiction potential and misuse patterns. Litigation and regulatory review examined whether dosage strength, extended-release mechanisms, and marketing narratives amplified foreseeable harm. As with tobacco, the question became whether institutional design shaped consumption trajectories in ways that corporate actors understood. Courts and policymakers began to evaluate the alignment between internal research and external representation. The tobacco precedent normalized this form of architectural inquiry.

Food systems and consumer goods industries likewise face questions about engineered consumption. High-sugar and high-fat products have been analyzed in terms of formulation, portion sizing, and marketing toward children. While these debates remain legally and scientifically complex, the underlying principle echoes tobacco litigation: when products are structured to maximize repeat use while minimizing awareness of risk, accountability extends beyond individual choice. The inquiry shifts from “Did consumers know?” to “How was the product designed to influence behavior?” This reframing owes much to the jurisprudential developments of the late twentieth century.

Digital platforms introduce another frontier in which engagement metrics, algorithmic curation, and interface design shape user behavior. Features engineered to maximize screen time or interaction can produce patterns of dependency analogous, though not identical, to chemical addiction. Scholars increasingly employ the language of architecture and design to analyze how platforms incentivize continued use. While legal doctrine in this domain remains unsettled, the tobacco cases provide a historical template for connecting internal research, behavioral targeting, and foreseeable harm. The conceptual shift from habit to engineered outcome informs these emerging debates.

Corporate accountability today operates within a landscape partially shaped by tobacco’s legal reckoning. Companies are expected to anticipate foreseeable harms arising from design decisions and to disclose internal knowledge relevant to consumer safety. Regulatory bodies increasingly scrutinize how research findings are communicated and whether risk disclosures align with internal assessments. The possibility that internal documents may become public evidence exerts a disciplining effect on corporate strategy and communication. Legal analysis now considers whether institutional incentives encourage the suppression or distortion of knowledge. Public expectations regarding transparency have shifted accordingly. Corporations operate under the assumption that design decisions, marketing data, and internal correspondence may later be subject to judicial review. The language of foreseeability and architecture has become embedded in regulatory culture. Institutional architecture is no longer shielded entirely by appeals to consumer autonomy.

The enduring legacy of tobacco litigation lies in its redefinition of responsibility as structural rather than purely individual. By revealing how product design, marketing strategy, and information management can converge to produce predictable dependency, the cases expanded the scope of legal and ethical evaluation in American jurisprudence. Responsibility is now understood to include not only overt deception but also the deliberate calibration of systems that influence behavior. Modern corporate accountability incorporates analysis of internal knowledge, risk assessment processes, and incentive structures that shape design choices. The recognition that dependency can be engineered reshaped regulatory logic across sectors. Courts increasingly examine how foreseeable harm intersects with strategic decision-making within corporations. The tobacco precedent underscores that institutional power carries obligations proportional to its capacity to shape consumer environments. It also illustrates how delay and doubt can function as strategic tools within corporate systems. Contemporary legal debates about digital engagement, pharmaceutical marketing, and consumer product safety echo the structural reasoning first crystallized in tobacco cases. Although industries differ in substance and scale, the governing principle endures. When harm is embedded within architecture, and when internal awareness accompanies that design, accountability extends to the institution itself. The shift from personal fault to structural responsibility remains one of the most consequential legacies of late twentieth-century tobacco litigation.

Conclusion: Institutional Design and the Politics of Denial

The history of Big Tobacco demonstrates that denial was never merely rhetorical improvisation in the face of crisis. It was structurally integrated into the organization of research, marketing, and public communication. Product design engineered dependency, while narrative design engineered delay. Addiction and uncertainty operated in tandem, reinforcing one another across decades. Public controversy masked internal coherence. What appeared as fragmented dispute was sustained by coordinated institutional strategy.

The legal exposure of internal documents disrupted this architecture by collapsing the distance between knowledge and narrative. Courts confronted evidence that addiction was understood, cultivated, and publicly minimized. The defense of personal choice proved insufficient once design intent and youth targeting were documented. Responsibility shifted from the psychology of smokers to the architecture of corporate decision-making. The politics of denial gave way to the jurisprudence of design.

This shift has broader implications for how modern societies evaluate harm. When institutions possess the technical capacity to shape behavior at scale, claims of neutrality demand scrutiny. The tobacco precedent demonstrates that foreseeability and internal awareness matter as much as overt misrepresentation. Design choices embed incentives, shape consumption patterns, and influence vulnerability. The language of habit obscures structural influence. By reframing addiction as engineered outcome, courts introduced a durable analytical tool for assessing corporate power. Denial can function as architecture, not merely speech. When doubt is systematically cultivated, it becomes part of the institutional mechanism sustaining harm.

Institutional design stands at the center of contemporary debates about accountability. The tobacco industry revealed how dependency, youth targeting, scientific manipulation, and narrative control can converge into a coherent system that resists reform for generations. Legal reckoning did not eliminate corporate power, but it altered the framework through which that power is judged. Responsibility now attaches not only to what institutions say but to how they structure products, incentives, and knowledge flows. The politics of denial operates most effectively when architecture remains invisible. The historical record of tobacco litigation exposes that invisibility as constructed rather than natural. In doing so, it affirms a principle with enduring relevance: when harm is foreseeable, internally recognized, and embedded within design, accountability must reach the institution itself. Corporate strategy cannot be insulated indefinitely by appeals to consumer autonomy or scientific ambiguity. Structural power carries structural responsibility.

Bibliography

- Brandt, Allan M. The Cigarette Century: The Rise, Fall, and Deadly Persistence of the Product That Defined America. New York: Basic Books, 2007.

- —-. “Inventing Conflicts of Interest: A History of Tobacco Industry Tactics.” American Journal of Public Health 102:1 (2012), 63-71.

- Dani, John A. and David JK Balfour. “Historical and Current Perspective on Tobacco use and Nicotine Addiction.” Trends in Neuroscience 34:7 (2011), 383-392.

- Master Settlement Agreement, 1998.

- McCaffree, Donald Robert and Neeraj R. Desai. “Is Big Tobacco Still Trying to Deceive the Public? This Is No Time to Rest on Our Laurels.” CHEST Journal 153:5 (2018), 1085-1086.

- Oreskes, Naomi, and Erik M. Conway. Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Climate Change. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2010.

- Proctor, Robert N. Golden Holocaust: Origins of the Cigarette Catastrophe and the Case for Abolition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

- United States v. Philip Morris USA Inc., 449 F. Supp. 2d 1 (D.D.C. 2006).

- U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1964.

- Wailoo, Keith. Pushing Cool: Big Tobacco, Racial Marketing, and the Untold Story of the Menthol Cigarette. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.18.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.