The encomienda offers a historical example of how institutions claiming neutrality or benefit can embed exploitative feedback loops within their design.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Benevolence as Political Language

Spanish expansion into the Americas in the sixteenth century required more than ships, soldiers, and settlers. It required justification. Conquest, labor extraction, and the reordering of indigenous societies demanded an intellectual framework capable of reconciling imperial ambition with Christian moral doctrine. The language of benevolence emerged as a crucial tool in this effort. Rather than presenting domination as naked force, imperial defenders framed Spanish authority as guardianship, discipline, and civilizing instruction. Violence and labor were recast as necessary instruments in the elevation of supposedly inferior peoples. In this rhetorical transformation, coercion was not denied; it was moralized.

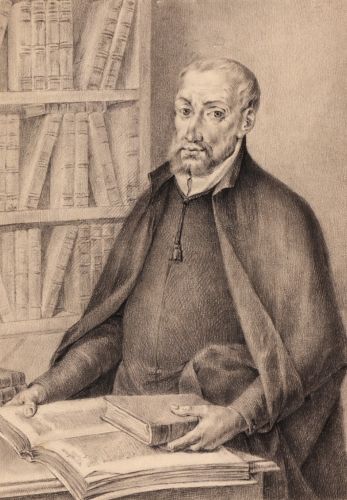

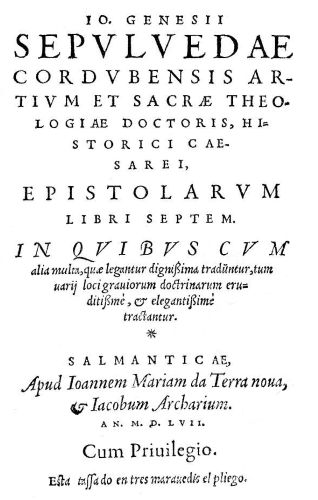

Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda stands among the most prominent articulators of this framework. Drawing upon Aristotelian notions of natural hierarchy and Thomistic theology, Sepúlveda argued that certain peoples were naturally suited to tutelage under more “civilized” rulers. Indigenous societies of the Americas were depicted as rational but deficient, capable of improvement under firm supervision. In Democrates Segundo, O De Las Justas Causas, Sepúlveda adapted Aristotle’s concept of natural slavery to the New World, contending that Spanish rule could be justified as a corrective response to perceived barbarism and moral disorder. War and subjugation were framed not as aggression but as instruments of moral reform. Within this schema, labor obligations were not exploitation but corrective discipline, a means by which indigenous communities might be habituated to industriousness and Christian virtue. Spanish oversight appeared as a beneficent intervention designed to cultivate order, Christianity, and productivity. The moral vocabulary of improvement obscured the asymmetry of power embedded within the arrangement, transforming coercive hierarchy into a purportedly natural and providential relationship.

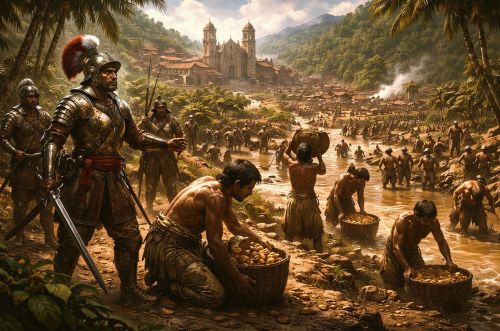

The encomienda system embodied this rhetoric in institutional form. Under its provisions, Spanish settlers were granted rights to tribute and labor from indigenous communities while assuming responsibility for their protection and Christian instruction. The formal structure emphasized reciprocity: guardianship in exchange for service. Yet this apparent balance concealed a profound structural inequality. Tribute quotas and labor drafts were not occasional impositions but recurring requirements that tied indigenous communities to Spanish authority in durable ways. The system’s defenders could claim benevolence because the language of obligation was framed as paternal care rather than extraction.

To examine benevolence as political language is to recognize its function within imperial governance. The encomienda did not operate despite moral justification; it operated through it. Assertions of protection and improvement provided legitimacy to a system whose architecture embedded dependency into everyday life. Because guardianship was presented as a moral duty, structural coercion could be interpreted as temporary discipline rather than enduring subordination. Harm could be portrayed as the result of individual excess rather than institutional design, allowing officials to attribute suffering to rogue encomenderos instead of to tribute structures or labor cycles themselves. Only when critics began to interrogate the system’s recurring demands and structural incentives did the limits of the benevolence narrative become visible. In the early Spanish Empire, the language of guardianship did not merely accompany exploitation. It translated domination into a moral register that made it administratively durable and politically defensible.

Legal and Theological Foundations: Sepúlveda’s Defense of Hierarchy

Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda’s defense of Spanish dominion rested upon a synthesis of classical philosophy and Christian theology that sought to provide legal coherence to imperial expansion. At the center of his argument stood Aristotle’s doctrine of natural hierarchy, particularly the notion that some human beings were “slaves by nature,” lacking the rational capacity to govern themselves fully. Sepúlveda did not merely cite Aristotle; he adapted him. Indigenous peoples of the Americas were described as possessing reason in a diminished or immature form, sufficient for instruction but insufficient for autonomous political life. This formulation allowed Sepúlveda to avoid denying indigenous humanity outright while still justifying Spanish tutelage. Hierarchy became not an accident of conquest but a reflection of natural order.

The theological dimension of this hierarchy reinforced its legal implications. Drawing upon Thomistic interpretations of just war, Sepúlveda contended that war against indigenous societies could be justified if it aimed at correcting grave moral failings or idolatry. Conquest, in this framework, served as an instrument of spiritual and moral reform rather than mere territorial acquisition. The Spanish Crown was positioned not simply as a sovereign authority but as a divinely sanctioned agent of Christian civilization. Intervention could be portrayed as restorative rather than disruptive. Coercion, when exercised to eliminate practices deemed barbarous or sinful, was framed as a form of charity aimed at salvation. The logic was circular but internally consistent: indigenous societies were deficient; deficiency justified intervention; intervention promised improvement. Within this structure, violence could be recoded as discipline, and discipline as benevolence. By embedding imperial action within a teleology of Christian advancement, Sepúlveda endowed Spanish authority with moral inevitability.

Sepúlveda’s arguments also engaged with debates over sovereignty and political community. Indigenous polities were characterized as lacking the structures necessary for legitimate self-rule according to European standards of governance. Practices such as human sacrifice were invoked as evidence of moral deficiency, reinforcing claims of inferiority. By depicting indigenous societies as unstable or unjust, Sepúlveda implied that Spanish governance introduced order rather than disruption. The encomienda system, when viewed through this lens, appeared as an extension of legitimate authority rather than as an arbitrary imposition.

Important to Sepúlveda’s reasoning was the distinction between domination and guidance. Spanish authority was cast as corrective, not exploitative. Labor obligations imposed upon indigenous communities could be interpreted as pedagogical tools, designed to instill discipline, industriousness, and Christian virtue. The asymmetry of power was reframed as necessary supervision, analogous to that of a guardian over a ward or a teacher over a pupil. This rhetorical distinction proved crucial in insulating the system from moral scrutiny. If inequality was temporary tutelage, then resistance could be characterized as ingratitude or disorder rather than as protest against coercion. By emphasizing instruction over extraction, Sepúlveda’s framework obscured the economic incentives embedded within imperial policy. The language of guidance masked the structural permanence of dependency, rendering long-term subordination compatible with claims of moral responsibility.

The legal and theological foundations constructed by Sepúlveda did not operate in isolation from administrative practice. They furnished imperial officials with an intellectual vocabulary capable of legitimizing institutional arrangements already in place. The encomienda system drew strength from these arguments, which translated extraction into obligation and hierarchy into providential design. In grounding imperial authority in natural and divine order, Sepúlveda provided more than defense; he supplied a framework within which structural exploitation could be rendered morally intelligible.

Institutional Design: How the Encomienda System Functioned

The encomienda system translated ideological justification into administrative practice. At its core, the Crown granted individual Spaniards, known as encomenderos, the right to receive tribute and labor from designated indigenous communities. These grants did not transfer ownership of land in theory, nor did they formally enslave the indigenous population. Instead, the arrangement established a structured obligation: indigenous communities were required to provide labor, goods, or monetary tribute, while the encomendero assumed responsibility for protection and Christian instruction. The system’s language emphasized stewardship rather than possession. Yet this distinction, while legally significant, did little to alter the asymmetry of power embedded within its design.

Tribute obligations were rarely incidental or sporadic. They were regularized through administrative expectations that defined quotas, cycles, and labor drafts. Indigenous communities were compelled to allocate a portion of their population to work in mines, fields, or domestic service under Spanish supervision. This labor extraction disrupted existing economic patterns and redirected productivity toward colonial demands. Because tribute requirements were ongoing, communities could not easily reconstitute autonomous systems of subsistence or trade. Recurrence, not exception, defined the relationship. Dependency emerged from repetition.

The institutional framework also relied upon the preservation of indigenous communal structures, but in altered form. Rather than dismantling native leadership outright, Spanish authorities frequently co-opted local elites, incorporating them into the system as intermediaries responsible for organizing tribute and labor. This strategy reduced administrative burden while embedding colonial oversight within preexisting hierarchies. Indigenous leaders were placed in the position of enforcing obligations upon their own communities, collecting tribute, assigning laborers, and ensuring compliance with Spanish demands. Such arrangements blurred the line between traditional authority and colonial enforcement. Authority was reoriented rather than erased. The system maintained the appearance of continuity while redirecting its function toward imperial extraction. By channeling colonial control through indigenous structures, the encomienda entrenched dependency without requiring constant direct supervision from Spanish officials.

Christian instruction functioned as both obligation and justification. Encomenderos were formally charged with ensuring the spiritual education of those under their supervision. In practice, religious conversion was intertwined with labor discipline. Attendance at doctrinal instruction occurred alongside work requirements, and mission settlements often reorganized indigenous populations into concentrated reductions that facilitated oversight. Spiritual tutelage and economic obligation operated within the same administrative framework. The promise of salvation coexisted with the demand for tribute, reinforcing the paternal language that framed dependency as guidance.

Youth vulnerability intensified the system’s reach. Younger members of indigenous communities were particularly susceptible to assimilation within mission settlements and labor drafts. Removal from traditional kin networks at formative stages made cultural and linguistic continuity more fragile. Instruction in Christian doctrine often targeted children and adolescents, whose habits and beliefs were considered more malleable. At the same time, working-age youth represented essential labor power for mines and agricultural estates. The regular extraction of young laborers strained demographic stability and undermined generational reproduction of indigenous authority structures. Because tribute cycles were continuous, this disruption did not occur once but repeatedly, embedding instability within the social fabric. Institutional design exploited formative stages of life, aligning economic extraction with cultural transformation.

The functioning of the encomienda reveals that exploitation was not merely the result of individual cruelty but of administrative structure. The system’s durability derived from its formalization of reciprocal language combined with recurrent extraction. Even well-intentioned encomenderos operated within an arrangement that required sustained tribute and labor to justify its existence. By preserving indigenous communities as tribute-bearing units, the Crown ensured a stable source of labor without overtly declaring enslavement, thereby maintaining legal distance from the harsher realities of forced service. Dependency was constructed through quota, supervision, and repetition, making harm predictable rather than accidental. The architecture of the system made exploitation routinized and defensible within the language of imperial stewardship, allowing responsibility to be diffused while the structure itself remained intact.

Dependency by Design: Psychological and Social Conditioning

The encomienda system did not rely solely on legal obligation or military force. Its durability depended upon psychological and social conditioning that reshaped how indigenous communities understood authority, labor, and survival. Tribute cycles established a rhythm of expectation in which compliance became routine. Because obligations recurred predictably, resistance required sustained disruption rather than momentary defiance. Repetition normalized subordination. The system trained communities to anticipate demand and to reorganize daily life around colonial extraction.

Religious instruction deepened this conditioning. Missionary activity was formally distinct from encomienda administration, yet in practice the two operated in tandem and often in overlapping spaces. Christian doctrine framed obedience to Spanish authority as compatible with spiritual salvation, presenting hierarchy as part of a divinely ordered cosmos rather than as a product of conquest. Sermons, catechisms, and sacramental participation introduced new moral vocabularies that linked discipline with virtue. The language of guardianship and tutelage encouraged acceptance of inequality as temporary guidance necessary for spiritual maturation. Confession reinforced internalized accountability, directing moral reflection inward rather than toward institutional structures. In this setting, compliance could be understood not only as pragmatic but as righteous. Spiritual and economic dependency intertwined, each reinforcing the other within a single institutional environment that fused salvation with submission.

Social reorganization further entrenched dependency. Indigenous populations were frequently concentrated into reducciones, settlements designed to facilitate oversight, conversion, and labor mobilization. These reorganized spaces disrupted traditional patterns of kinship, authority, and subsistence. Physical proximity under Spanish supervision made collective resistance more difficult while simplifying tribute collection. Communal life was reshaped to align with administrative convenience. The alteration of space functioned as a tool of governance, narrowing the autonomy of communities and embedding oversight into daily routines.

The erosion of traditional leadership structures compounded this transformation. Although local elites were incorporated as intermediaries, their authority became contingent upon compliance with Spanish demands rather than on reciprocal obligations to their communities. Indigenous leaders were incentivized to fulfill tribute quotas to preserve their position and avoid punishment. This shift altered the basis of legitimacy. Authority no longer derived primarily from communal consensus or ancestral standing but from alignment with colonial expectations. Leaders who resisted risked removal or marginalization, while those who cooperated could retain limited privileges within the imposed system. Authority shifted from reciprocal community stewardship to enforcement of external obligation. This restructuring weakened alternative sources of legitimacy that might have challenged colonial authority and redirected internal power dynamics toward maintenance of extraction. Social conditioning operated not only at the level of individual laborers but within the very mechanisms of communal governance, embedding colonial priorities into indigenous political life.

Dependency became systemic rather than episodic. Psychological adaptation to recurring demands, religious reframing of hierarchy, spatial concentration, and leadership co-optation produced a feedback loop that stabilized extraction. Communities adjusted to the rhythms imposed upon them, often out of necessity rather than consent. The system did not require constant overt violence because its design structured expectations and incentives in ways that made compliance appear rational. Dependency was sustained not by illusion alone but by the deliberate alignment of institutional pressures with social survival.

Youth and Vulnerability: The Targeting of Malleable Populations

Youth occupied a particularly vulnerable position within the encomienda system. Although tribute obligations were formally assigned to communities, the labor demands that sustained colonial extraction frequently fell upon young and physically capable individuals. Adolescents and young adults represented essential productive capacity, adaptable to mining, agriculture, and domestic service. Their relative physical resilience made them attractive targets for labor drafts, while their social position within kin networks rendered their removal destabilizing. The system’s reliance on recurring tribute cycles ensured that youth were not incidental participants but structural necessities.

Missionary efforts amplified this vulnerability by focusing intensely on the formation of young minds. Catechetical instruction, schooling in Christian doctrine, and participation in liturgical life often concentrated on children and adolescents. Youth were perceived as more malleable, more receptive to religious discipline, and more likely to internalize new cultural norms. Conversion functioned as both spiritual transformation and social reorientation. As young people absorbed Spanish language, ritual, and moral vocabulary, generational continuity within indigenous communities weakened. Cultural transmission, once anchored in precolonial cosmologies and social practices, became increasingly mediated through colonial frameworks.

The disruption of generational structures carried long-term consequences. When working-age youth were repeatedly mobilized for tribute labor, family economies suffered and demographic balances shifted. Agricultural cycles were interrupted, and communal labor obligations were redistributed unevenly, placing strain on elders and younger children who remained behind. Prolonged absence from home limited the transfer of skills tied to traditional subsistence practices and ceremonial life. In mining regions especially, labor drafts exposed young workers to physically hazardous environments, disease, and exhaustion, reducing life expectancy and weakening the capacity for community reproduction. The erosion of intergenerational continuity meant that knowledge systems, leadership preparation, and kinship networks could not be sustained without distortion. Pressures compounded, producing structural fragility within indigenous societies that extended far beyond the immediate period of labor extraction. Institutional design intersected with biological and social vulnerability in ways that reshaped both present stability and future continuity.

The language of tutelage provided moral cover for these disruptions. Spanish defenders of the system described indigenous youth as in need of guidance, discipline, and instruction, portraying supervision as a benevolent investment in their moral development. The rhetoric of protection implied that exposure to Spanish authority would cultivate order and Christian virtue. Yet this paternal framing masked the structural incentives driving labor allocation. The promise of moral formation coexisted with economic necessity, and instruction rarely displaced extraction as the primary institutional priority. Youth were targeted not solely because they required education but because they represented adaptable and renewable labor power within a growing colonial economy. By conflating guidance with obligation, imperial administrators could present recurring labor drafts as components of civilizing pedagogy rather than as mechanisms of resource transfer. Benevolence and utility converged in the same administrative calculus, rendering exploitation defensible within a language of improvement.

By concentrating labor demands and cultural transformation upon younger generations, the encomienda system embedded dependency across time. Youth exposed to recurring cycles of tribute and instruction matured within an environment structured by colonial expectation. Their adulthood unfolded within the parameters set by imperial governance rather than by preexisting communal autonomy. The targeting of malleable populations ensured that dependency would not be confined to a single generation. Institutional design extended its reach forward, shaping not only immediate compliance but the social reproduction of subordination.

Critique and Exposure: Las Casas and Structural Accountability

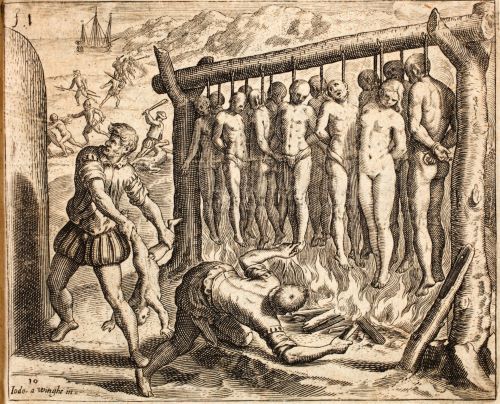

The most forceful contemporary challenge to the encomienda system emerged from Bartolomé de las Casas, whose critique shifted attention from isolated acts of cruelty to the structure that enabled them. Las Casas did not deny that individual encomenderos committed abuses, but he insisted that violence, demographic collapse, and coercive labor were predictable outcomes of the system itself rather than aberrations within it. In A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies, he documented recurring patterns of forced labor, dispossession, brutality, and depopulation that unfolded across multiple regions of the Americas. The repetition of these patterns, in his view, exposed the inadequacy of attributing suffering to personal excess alone. Tribute requirements and labor drafts created conditions in which abuse was structurally incentivized. By foregrounding recurrence rather than exception, Las Casas reframed the moral debate. The problem, he argued, lay not only in misconduct but in the architecture of tribute and labor that rewarded extraction and normalized coercion.

The Valladolid debate of 1550–1551 crystallized this confrontation. Sepúlveda defended hierarchy and coercive tutelage as morally justified, while Las Casas contended that indigenous peoples possessed full rational capacity and could not be subjected to forced subordination. Although the debate did not produce a definitive institutional transformation, it marked a significant intellectual turning point. For Las Casas, exploitation flowed from structural incentives embedded in the encomienda. If tribute quotas and labor drafts were sustained by economic reward, then even well-intentioned overseers would perpetuate harm. Accountability required interrogation of institutional design rather than reliance on improved personal virtue.

Las Casas’s critique also exposed the disjunction between legal rhetoric and lived reality. While encomienda grants emphasized protection and Christian instruction, the demographic devastation of indigenous populations revealed a stark contradiction between promise and outcome. Forced labor in mines and agricultural estates, combined with disease, displacement, and overwork, produced catastrophic decline that could not plausibly be dismissed as accidental. The persistence of these consequences across diverse colonial contexts suggested structural causation rather than localized failure. Las Casas advanced an early argument for what might be termed institutional responsibility: when predictable harm accompanies a recurring administrative pattern, the pattern itself must be scrutinized. By shifting attention from individual morality to systemic design, he challenged imperial authorities to confront the possibility that guardianship language functioned as cover for extraction. His intervention pressed the Crown to acknowledge that benevolent intent, even if sincerely professed, could not absolve a structure that consistently generated suffering.

Although reform efforts such as the New Laws of 1542 attempted to curb excesses and limit the inheritance of encomiendas, resistance from colonial elites blunted their impact. Structural incentives remained powerful, and enforcement proved uneven. Nevertheless, Las Casas’s intervention altered the moral vocabulary of imperial governance. By directing critique toward systemic design, he made it increasingly difficult to dismiss suffering as accidental or aberrational. The encomienda system could no longer be defended solely by appealing to benevolent intention. The debate revealed that institutional architecture, not individual disposition alone, determined the persistence of exploitation.

Reform, Resistance, and the Limits of Change

The mounting criticism of the encomienda system, particularly from figures such as Bartolomé de las Casas, compelled the Spanish Crown to confront the growing dissonance between imperial rhetoric and colonial reality. Reports of demographic collapse, forced labor, and endemic abuse reached royal authorities with increasing urgency. The Crown, mindful of both moral responsibility and political legitimacy, sought to assert greater oversight over colonial administration. Reform was framed as a corrective to excess, not as a repudiation of imperial authority. The goal was to preserve sovereignty while mitigating the most visible manifestations of exploitation.

The New Laws of 1542 represented the most ambitious reform effort of the period. Among their provisions was the prohibition of indigenous enslavement and the attempt to end the inheritance of encomiendas upon the death of their holders. By limiting perpetuity, the Crown aimed to prevent the consolidation of quasi-feudal power structures in the colonies and to reassert direct royal authority over subject populations. The laws sought to restore indigenous communities to more explicit royal protection and to reduce the autonomy of encomenderos whose economic power had begun to rival administrative oversight. In principle, these reforms acknowledged that structural incentives embedded within the encomienda encouraged abuse and demographic decline. They marked a rare moment in which imperial legislation recognized that recurring harm flowed from systemic design rather than from isolated misconduct. Yet the language of reform continued to balance correction with preservation, seeking to temper extraction without dismantling imperial control itself.

Resistance from colonial elites, however, revealed the depth of institutional entrenchment. Encomenderos viewed reform as a direct threat to economic security and social status. In Peru, opposition escalated into armed rebellion under Gonzalo Pizarro, demonstrating that vested interests would not yield without confrontation. Even where outright revolt did not occur, enforcement proved inconsistent. Colonial officials, often themselves beneficiaries of the system, hesitated to dismantle arrangements that underpinned local economies. Reform collided with material incentives deeply embedded in colonial society.

The encomienda system did not disappear so much as evolve. Alternative labor arrangements, such as repartimiento systems, emerged in different regions, modifying but not eliminating extraction. Tribute obligations persisted, though sometimes under altered legal frameworks that claimed closer alignment with royal supervision. These transitions allowed the Crown to assert reformist intent while maintaining steady flows of labor and revenue. The formal weakening of hereditary encomiendas did not automatically translate into indigenous autonomy. Instead, colonial administration recalibrated mechanisms of control, dispersing authority more broadly while preserving dependency at the community level. Institutional resilience lay in adaptability. By reshaping the form of extraction without relinquishing its substance, the empire sustained its economic foundations while publicly affirming moral concern.

These developments underscore the limits of reform when structural incentives remain intact. The Crown could legislate moral correction, but enforcement depended upon administrative will, local compliance, and the continued profitability of colonial production. Where mining, agriculture, and tribute fueled imperial wealth, resistance to meaningful transformation proved persistent and rational from the perspective of colonial stakeholders. Reform initiatives frequently sought compromise, attempting to reconcile humanitarian rhetoric with fiscal necessity. The resulting measures mitigated the most egregious abuses while preserving the broader architecture of dependency. Structural extraction endured because it was interwoven with imperial finance, social hierarchy, and political authority. Dependency, once institutionalized, proved resistant not only to critique but to incremental legislative adjustment.

The history of reform within the encomienda system illustrates a broader dynamic of institutional endurance. Critique exposed harm and prompted legal adjustment, yet structural dependency proved difficult to eradicate. Resistance by entrenched interests constrained transformation, while the Crown’s reliance on colonial productivity tempered its willingness to enforce sweeping change. Reform altered the language and occasionally the mechanics of extraction, but it did not fundamentally sever the relationship between labor obligation and imperial authority. The limits of change lay not in the absence of awareness but in the persistence of design.

Enduring Legacies: Structural Echoes in Contemporary Latin America

Although the encomienda system formally disappeared centuries ago, its structural imprint did not vanish with it. Institutions rarely dissolve without transmitting elements of their design into successor arrangements. In much of Latin America, the early embedding of hierarchical labor relations, tribute logic, and racialized stratification shaped subsequent social formations in ways that were subtle but durable. The transition from encomienda to hacienda, repartimiento, and later estate systems did not represent a rupture but an evolution in administrative technique. While legal terminology changed and formal obligations were modified, patterns of concentrated authority over land and labor often persisted beneath the surface. Early colonial governance normalized asymmetrical relationships between elite overseers and subordinated communities, embedding dependency within economic and social structures. The durability of these arrangements suggests that institutional architecture, once naturalized through repetition and moral justification, can influence developmental trajectories long after its original legal form has ended.

One of the most visible legacies lies in patterns of land inequality. Colonial systems tied indigenous labor to elite control, even when formal ownership structures differed from later estate models. Tribute relationships and administrative privileges facilitated consolidation of land and authority in the hands of colonial elites and their descendants. As encomienda grants evolved into more entrenched landholding systems, the foundations for large estates were strengthened. In several countries across the Andes and Mesoamerica, highly unequal land distribution remains a defining feature of agricultural life. Contemporary land reform debates frequently trace their historical origins to colonial-era arrangements that privileged elite extraction over communal autonomy. Although modern inequality cannot be reduced solely to encomienda, early institutional design contributed to structural imbalances in property and labor relations that proved resistant to reversal and reform.

Racialized hierarchy also endures as a social reality. The encomienda reinforced a stratified colonial order in which Spanish and creole elites occupied positions of authority while indigenous populations were subordinated economically and politically. Over generations, this hierarchy crystallized into caste systems and later into racialized class stratification. Today, indigenous communities in many Latin American nations continue to experience disproportionate poverty, limited access to education, and underrepresentation in political institutions. These disparities reflect layered historical processes, yet colonial institutionalization of inequality established durable foundations for exclusion.

Economic orientation offers another line of continuity. The encomienda system integrated indigenous labor into extractive colonial economies focused on mining and export agriculture. Wealth flowed outward to imperial centers, while local diversification remained secondary. Even after independence, many Latin American economies continued to rely heavily on commodity extraction and export dependence. Modern debates surrounding resource nationalism, mining regulation, and agrarian reform often unfold within structural conditions shaped during the colonial period. The persistence of extractive economic models cannot be attributed to encomienda alone, but the early prioritization of externalized profit over internal development formed a powerful precedent.

Political culture likewise bears traces of colonial paternalism. The language of guardianship, tutelage, and benevolent oversight that justified encomienda reappeared in later forms of centralized authority. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, political leaders frequently framed hierarchical governance as necessary guidance for populations portrayed as unprepared for full autonomy. While such rhetoric evolved in secular rather than explicitly theological terms, the logic of protective hierarchy remained recognizable. Centralized authority was often defended as stabilizing, corrective, or developmental, echoing earlier justifications that equated control with improvement. These recurring patterns do not indicate simple replication of colonial ideology, but they suggest that institutional narratives of benevolent dominance can become embedded within political culture. Institutional memory, even when implicit, shapes how authority is articulated and legitimized across generations.

None of these continuities imply historical inevitability. Latin America’s contemporary conditions are shaped by industrialization, global markets, Cold War interventions, democratic transitions, and internal reform movements. Yet the early embedding of dependency and hierarchy within colonial governance influenced the parameters within which later change unfolded. The encomienda did not singlehandedly determine modern inequality, but it contributed to structural patterns that proved remarkably persistent. Institutional architecture, once aligned with economic incentive and cultural normalization, can cast a long shadow across centuries.

Conclusion: Institutional Architecture and the Politics of Benevolence

The history of the encomienda system demonstrates that exploitation can be embedded within institutional architecture while being defended through the language of benevolence. Spanish imperial authorities did not typically deny that labor was extracted or that hierarchy structured colonial life. Rather, they reframed these realities as components of guardianship and civilizing mission, situating coercion within a narrative of moral responsibility and Christian obligation. Ideology and administration operated in tandem. Legal theory, theological justification, tribute quotas, missionary activity, and communal restructuring formed an integrated design that rendered dependency durable. The system’s coherence lay in its ability to align moral vocabulary with economic necessity, presenting recurring extraction as protective oversight. Harm was not an unintended byproduct but a foreseeable consequence of recurring institutional patterns that privileged imperial stability over indigenous autonomy. The politics of benevolence transformed asymmetry into order and dependency into governance.

By tracing the arguments of Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda alongside the administrative functioning of encomienda, the distinction between individual abuse and systemic design becomes central. Exploitation persisted not merely because some encomenderos were cruel, but because the system rewarded extraction and normalized asymmetry through routine practice. Tribute cycles, labor drafts, youth targeting, and religious conditioning reproduced vulnerability across generations. Even reform efforts struggled to dismantle dependency because they operated within a framework that continued to prioritize imperial productivity and colonial hierarchy. The Crown could condemn excess while maintaining the structures that incentivized it. Institutional stability proved more resilient than moral discomfort, and legal modification often preserved the core logic of extraction. Responsibility cannot be confined to personal disposition; it must be located within the architecture that structured incentives and expectations.

The intervention of Bartolomé de las Casas marked a critical intellectual shift toward structural accountability. By exposing the recurring nature of demographic decline and forced labor, he challenged the adequacy of benevolent rhetoric. Yet the endurance of modified extraction systems after reform underscores the limits of critique when economic incentives remain intact. Institutional change required more than condemnation; it demanded transformation of the architecture itself. Without such restructuring, dependency adapted and persisted under new legal forms.

The encomienda offers a historical example of how institutions claiming neutrality or benefit can embed exploitative feedback loops within their design. Benevolence, when coupled with structural asymmetry, becomes a political instrument capable of sustaining domination. The politics of guardianship provided legitimacy, while administrative repetition ensured continuity. Institutional architecture, not merely personal intention, shaped outcomes. In recognizing this dynamic, the history of the early Spanish Empire illuminates the enduring power of design in conditioning human behavior and distributing vulnerability.

Bibliography

- Aristotle. Politics. Translated by C. D. C. Reeve. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1998.

- Brunstetter, Daniel R. and Dana Zartner. “Just War against Barbarians: Revisiting the Valladolid Debates between Sepúlveda and Las Casas.” Political Studies 59:3 (2011), 733-752.

- Gibson, Charles. The Aztecs under Spanish Rule: A History of the Indians of the Valley of Mexico, 1519–1810. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1964.

- Hanke, Lewis. All Mankind Is One: A Study of the Disputation between Bartolomé de Las Casas and Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda in 1550 on the Religious and Intellectual Capacity of the American Indians. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1974.

- —-. The Spanish Struggle for Justice in the Conquest of America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1949.

- Las Casas, Bartolomé de. A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. Translated by Nigel Griffin. London: Penguin Books, 1992.

- Lockhart, James. The Nahuas after the Conquest: A Social and Cultural History of the Indians of Central Mexico, Sixteenth through Eighteenth Centuries. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1992.

- —-. Spanish Peru, 1532–1560: A Colonial Society. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1968.

- Orías, Paola A. Revilla. “Moving to Your Place: Labour Coercion and Punitive Violence against Minors under Guardianship (Charcas, Sixteenth through Eighteenth Centuries).” International Review of Social History 68:S31 (2023), 93-108.

- Pagden, Anthony. The Fall of Natural Man: The American Indian and the Origins of Comparative Ethnology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- —-. Spanish Imperialism and the Political Imagination: Studies in European and Spanish-American Social and Political Theory 1513-1830. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990.

- Romero-Toledo, Hugo. “Producing Territories for Extractivism: Encomiendas, Estancias and Forts in the Long-Term Political Ecology of Colonial Southern Chile.” Land 12:4 (2023), 857.

- Sepúlveda, Juan Ginés de. Democrates Alter, sive de justis belli causis apud Indios. Rome, 1550.

- Yeager, Timothy J. “Encomienda or Slavery? The Spanish Crown’s Choice of Labor Organization in Sixteenth-Century Spanish America.” The Journal of Economic History 55:4 (1995), 842-859.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.18.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.