“Nothing of comparable size, vocality, or persistence had ever happened before.”

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The Stonewall Riots of June 1969 have become a foundational rallying point for the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement in the United States and beyond. What began as a spontaneous eruption of resistance to police harassment in New York City’s Greenwich Village evolved into a global symbol of queer resilience, solidarity, and liberation. The legacy of Stonewall endures not only in the historical memory of pride parades and public commemorations, but in the shifting discourse on civil rights and the ongoing struggle for equality. This essay explores the historical significance of the riots, their transformative impact on LGBTQ+ activism, and their evolving place in cultural and political memory.

Historical Background

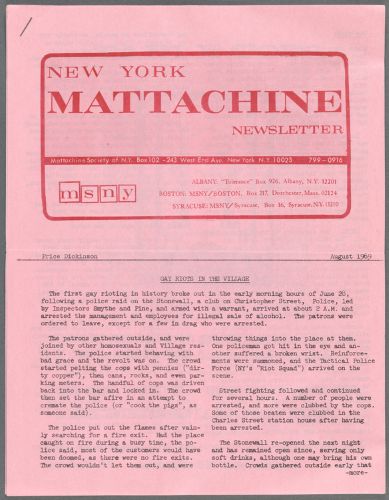

In the 1960s, homosexual acts were illegal in every U.S. state except Illinois, and same-sex relationships were heavily stigmatized. The LGBTQ+ community often gathered in clandestine spaces, such as bars and clubs, many of which operated without liquor licenses and under constant threat of police raids. The Stonewall Inn, located on Christopher Street, was one such bar run by the Mafia, serving as a rare refuge for marginalized queer individuals, including drag queens, transgender people, and homeless LGBTQ+ youth.

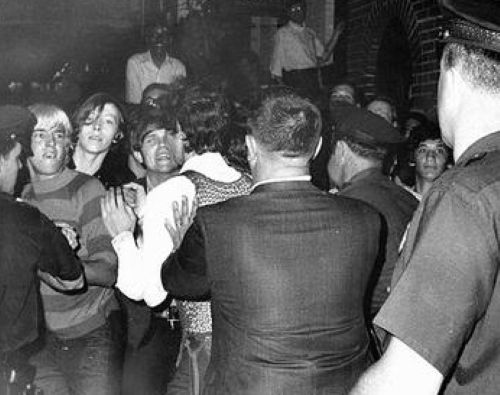

Police raids were common, and on June 28, 1969, a raid on the Stonewall Inn triggered a spontaneous uprising. For several nights, demonstrators clashed with law enforcement, throwing bottles, bricks, and resisting arrests. This defiance was unprecedented in scale and visibility. As historian Martin Duberman notes, “Nothing of comparable size, vocality, or persistence had ever happened before.”¹

Immediate Aftermath and the Rise of Gay Liberation

The Stonewall uprising galvanized LGBTQ+ individuals across the country. Within months, activists formed groups like the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) and the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA), which rejected the assimilationist strategies of earlier homophile organizations in favor of more radical, confrontational tactics.²

The first anniversary of the riots saw the organization of the Christopher Street Liberation Day March in 1970, recognized as the first Pride parade. The event was mirrored in cities like Los Angeles, Chicago, and San Francisco, institutionalizing public pride as a central element of queer identity and resistance.³

Political and Cultural Impact

The post-Stonewall era marked a decisive shift in LGBTQ+ politics. The movement diversified, addressing not only issues of decriminalization and discrimination but also broader questions of gender, race, and class. Stonewall’s most marginalized participants—particularly transgender women of color like Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera—became emblematic figures of intersectional activism.⁴

The riots also reframed public discourse on homosexuality. Rather than being pathologized or hidden, LGBTQ+ identities were asserted as valid and political. This visibility led to major legal and cultural shifts over the following decades, including the removal of homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders in 1973, and later milestones such as the legalization of same-sex marriage in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015).⁵

Stonewall in Historical Memory

The commemoration of Stonewall has itself become a site of contestation. As the LGBTQ+ movement gained mainstream acceptance, some critics argued that Pride events became commercialized and disconnected from their radical roots.⁶ Corporate sponsorships, law enforcement participation in Pride parades, and the marginalization of queer people of color have all been points of contention.

Nevertheless, the symbolic power of Stonewall remains potent. In 2016, President Barack Obama designated the Stonewall Inn and its surrounding area as a National Monument—the first U.S. federal monument dedicated to LGBTQ+ rights.⁷ This recognition underscored the event’s national and historical significance.

Global Influence

Stonewall’s legacy is not confined to the United States. The riots inspired LGBTQ+ movements worldwide, from London’s first Pride march in 1972 to more recent struggles in countries where homosexuality remains criminalized. The language of “Stonewall” is invoked globally as a metaphor for resistance, and June is internationally recognized as Pride Month in its honor.⁸

Continuing the Struggle

Despite significant progress, the struggle for LGBTQ+ rights is far from over. Transgender individuals, particularly trans women of color, continue to face disproportionate violence and discrimination. LGBTQ+ youth still experience high rates of homelessness and mental health issues, and many states in the U.S. have passed or proposed anti-LGBTQ+ legislation, particularly targeting transgender individuals.⁹

Stonewall’s enduring legacy lies in its reminder that progress is achieved through struggle, often led by the most marginalized. Its narrative challenges complacency and urges continued activism rooted in solidarity, inclusivity, and justice.

Conclusion

The Stonewall Riots were not the beginning of LGBTQ+ resistance, but they were a turning point that catalyzed a new era of visibility, pride, and activism. Their legacy is a complex tapestry of progress and setbacks, of celebration and struggle. As a symbol, Stonewall endures because it captures the spirit of defiance against systemic injustice—a defiance that remains as necessary today as it was in 1969.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Martin Duberman, Stonewall (New York: Dutton, 1993), 200.

- John D’Emilio, Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States, 1940-1970 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983), 234.

- Lillian Faderman, The Gay Revolution: The Story of the Struggle (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015), 143.

- Susan Stryker, Transgender History (Berkeley: Seal Press, 2008), 102–106.

- Susan Stryker, Transgender History.

- Sarah Schulman, Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993 (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021), 54.

- Barack Obama, “Presidential Proclamation – Establishment of the Stonewall National Monument,” The White House, June 24, 2016, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/06/24/presidential-proclamation-establishment-stonewall-national-monument.

- Michael Bronski, A Queer History of the United States (Boston: Beacon Press, 2011), 196.

- Human Rights Campaign, “State Equality Index 2023,” https://www.hrc.org/resources/state-equality-index.

Bibliography

- Bronski, Michael. A Queer History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press, 2011.

- Duberman, Martin. Stonewall. New York: Dutton, 1993.

- D’Emilio, John. Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States, 1940-1970. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983.

- Faderman, Lillian. The Gay Revolution: The Story of the Struggle. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015.

- Human Rights Campaign. “State Equality Index 2023.” https://www.hrc.org/resources/state-equality-index.

- Obama, Barack. “Presidential Proclamation – Establishment of the Stonewall National Monument.” The White House, June 24, 2016. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/06/24/presidential-proclamation-establishment-stonewall-national-monument.

- Schulman, Sarah. Let the Record Show: A Political History of ACT UP New York, 1987-1993. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021.

- Stryker, Susan. Transgender History. Berkeley: Seal Press, 2008.

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.19.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.