From Rome to today, damnatio memoriae reveals the universal struggle to control the past. It is a practice that transcends cultures and centuries, a reminder that memory is never neutral but always political.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Politics of Erasure

To erase a name, to smash a face from a monument, to blot out an inscription, these gestures reveal as much about the politics of memory as any act of construction. The Romans coined the term damnatio memoriae, the “condemnation of memory,” to describe the deliberate obliteration of a person’s presence from the collective record. Yet while the term is Latin, the practice was never uniquely Roman. Across cultures and centuries, rulers and communities have attempted to control history not only by building monuments but also by dismantling them.

The paradox is that erasure often preserves. Those whose names were struck from inscriptions, from Akhenaten to Trotsky, survive in historical consciousness precisely because efforts were made to silence them. Damnatio memoriae is less about forgetting than about shaping how future generations will remember.

Damnatio Memoriae in the Ancient World

Rome

The Roman world provides the most explicit articulation of damnatio memoriae as a formalized practice. When emperors fell, the Senate could decree that their memory be condemned. This meant their statues were pulled down, inscriptions mutilated, portraits defaced, and names chiseled from public records. Domitian, assassinated in 96 CE, was the object of such erasure: his images destroyed, his name scratched away, his reign re-narrated as tyranny.1 The act was performative, a way for the state to cleanse itself of his stain.

The case of Geta, murdered in 211 CE by his brother Caracalla, illustrates the brutality of erasure. Nearly every portrait of Geta in marble was hacked to remove his features, and inscriptions bearing his name were systematically altered.2 It was not enough to kill him; he had to be annihilated retroactively, removed from the fabric of Roman memory itself.

Egypt

Centuries earlier, pharaonic Egypt practiced its own form of memory condemnation. Hatshepsut, one of Egypt’s few female pharaohs, was deliberately effaced by her successor Thutmose III. Her cartouches were excised, her statues smashed, her monuments reinscribed.3 Akhenaten, the radical pharaoh who had sought to replace the traditional gods with Aten, fared similarly. After his death, his name was omitted from king lists, his temples dismantled, and his images destroyed. The damnatio memoriae of Akhenaten was theological as much as political: a divine correction aimed at restoring cosmic balance.

Mesopotamia and the Levant

The Mesopotamian kings who erected stelae to proclaim their deeds often faced successors eager to obliterate them. Names were scraped away, inscriptions mutilated, entire monuments repurposed. In the Hebrew Bible, the act of blotting out a name becomes a divine curse. Deuteronomy promises that the memory of Amalek would be erased from under heaven.4 The act of forgetting, therefore, was framed not only as a political tool but as a sacred punishment.

Greece

In democratic Athens, ostracism provided a more regulated version of political forgetting. Citizens inscribed names on shards of pottery, expelling individuals from civic life for a decade. While not exactly the destruction of images, it served as a form of sanctioned oblivion. Tyrants, by contrast, could see their statues toppled, their memorials dismantled. The politics of memory in Greece revolved around the tension between public sanction and popular fury.

Erasure in Asia: Dynasties and Forgetting

China

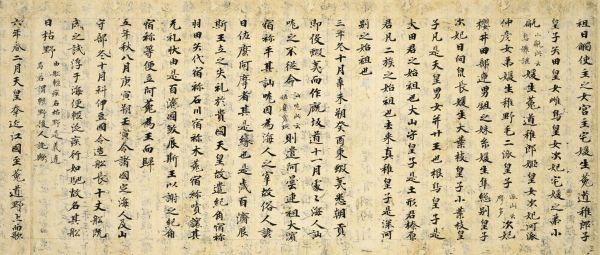

In imperial China, memory was inseparable from legitimacy. Dynasties rewrote history to buttress their authority. The Qin dynasty infamously ordered the burning of books and, according to tradition, buried scholars alive to erase Confucian teachings that threatened its ideological project.5 Later dynasties erased deposed rulers from official chronicles, retroactively redefining their reigns as illegitimate. The “Mandate of Heaven” was not only a theological concept but also a historiographical one: those who lost it could be excised from memory.

India and Japan

In India, rival dynasties frequently altered inscriptions to remove or overwrite the names of predecessors. Ashoka’s edicts provide a counter-example: instead of erasing, he inscribed a new moral order on stone, seeking to overwrite violence with memory of peace. In Japan, the Nihon Shoki chronicles reveal deliberate omissions, reshaping genealogies to legitimate ruling families while erasing rivals from the line of succession.

Medieval and Early Modern Variants

Christian Europe

The medieval West inherited the Roman impulse to erase. Chronicles often omitted heretics or political enemies, creating silences that spoke loudly of suppression. Richard II, after his deposition in 1399, had his image deliberately blackened and his reputation reframed as tyranny.6 Centuries later, Oliver Cromwell suffered posthumous execution: his body dug up, hanged, and beheaded, his skull displayed as a warning. Such acts were theatrical, designed to make memory itself a battlefield.

During the Reformation, erasure took visual form in iconoclasm. Protestant reformers smashed Catholic images; Catholics in turn sought to erase Protestant martyrs from their narratives. The destruction of stained glass and the mutilation of statues was not mere vandalism but a deliberate politics of memory.

Byzantine and Islamic Worlds

In Byzantium, iconoclasm intertwined theology and politics. Emperors who destroyed icons often faced damnatio themselves when their policies were reversed. In the Islamic world, caliphs who fell from favor could be erased from coinage or inscriptions. Shia and Sunni divisions generated selective remembering, elevating some figures while erasing others.

Indigenous Americas

Among the Maya, dynastic records inscribed on stelae reveal careful erasures when rulers were defeated. Entire glyphs were scratched away, leaving traces of deliberate forgetting. The Mexica similarly dishonored rivals after death, denying them the memorial rituals that sustained political legitimacy.

Modern Damnatio Memoriae

Revolutionary Erasures

The French Revolution exemplified modern erasure. Statues of kings were toppled, royal insignia effaced, streets renamed. Even the calendar was remade, with months stripped of Christian associations. Erasure became the foundation of new memory, a resetting of time itself.

Communist States

In the Soviet Union, damnatio memoriae took photographic form. Trotsky, once Lenin’s comrade, vanished from images and official histories after his fall. Nikolai Yezhov, head of the NKVD, was literally airbrushed out of photographs with Stalin.7 This visual manipulation was as effective as chiseling names from stone. North Korea continues the practice, rewriting genealogies and excising disfavored figures from its annals.

Nazi Germany and its Aftermath

The Nazis engaged in erasure by targeting Jewish culture: burning books, desecrating cemeteries, destroying synagogues. After 1945, Germany enacted its own counter-damnatio: banning Nazi monuments, outlawing swastikas, and forbidding commemoration of Hitler. Here, erasure became a moral imperative, a way of repudiating a past too terrible to celebrate.

Post-Colonial Erasures

The modern world abounds in examples. Statues of Cecil Rhodes fell in South Africa and Britain. King Leopold II’s monuments were attacked in Belgium. In the United States, Confederate memorials have been removed, bases renamed, and symbols contested. Iraq in 2003 offered one of the most televised damnation rituals of modern times: Saddam Hussein’s statue pulled down in Baghdad, an image meant to signal the erasure of a regime.

The Paradox of Forgetting

What unites these disparate examples is paradox. Erasure rarely achieves true oblivion. Akhenaten, remembered precisely because his name was struck from king lists, haunts Egyptology. Trotsky’s absence from photographs is more famous than his presence would have been. Confederate statues, once obscure, became global news when removed.

Damnatio memoriae thus produces memory even as it seeks to destroy it. The scar left by chisels, the empty pedestal, the airbrushed photograph; these absences testify more powerfully than monuments left untouched. To erase is to speak, to obliterate is to immortalize in absence.

Conclusion: Memory’s Fragile Endurance

From Rome to Baghdad, from the Maya to the Soviets, damnatio memoriae reveals the universal struggle to control the past. It is a practice that transcends cultures and centuries, a reminder that memory is never neutral but always political.

Yet erasure never triumphs fully. Memory is fragile, but it resists. The act of forgetting becomes its own kind of record, a testimony to the power that sought to silence. In the digital age, where archives proliferate and deletion is nearly impossible, the ancient impulse to erase remains, but its futility has never been clearer. The condemned will be remembered, if not in stone, then in the scars left by the chisel.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Harriet I. Flower, The Art of Forgetting: Disgrace and Oblivion in Roman Political Culture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 101–105.

- Eric R. Varner, Mutilation and Transformation: Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture (Leiden: Brill, 2004), 141–150.

- Joyce Tyldesley, Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh (London: Viking, 1996), 212–215.

- Deuteronomy 25:19.

- Mark Edward Lewis, Writing and Authority in Early China (Albany: SUNY Press, 1999), 56–62.

- Nigel Saul, Richard II (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 388–391.

- David King, The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin’s Russia (New York: Metropolitan Books, 1997), 44–51.

Bibliography

- Flower, Harriet I. The Art of Forgetting: Disgrace and Oblivion in Roman Political Culture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

- King, David. The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin’s Russia. New York: Metropolitan Books, 1997.

- Lewis, Mark Edward. Writing and Authority in Early China. Albany: SUNY Press, 1999.

- Saul, Nigel. Richard II. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

- Tyldesley, Joyce. Hatchepsut: The Female Pharaoh. London: Viking, 1996.

- Varner, Eric R. Mutilation and Transformation: Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture. Leiden: Brill, 2004.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.03.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.