The government conducted a census every five years.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Citizenship (civitas) in ancient Rome was a privileged political and legal status afforded to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Citizenship in ancient Rome was complex and based upon many different laws, traditions, and cultural practices. There existed several different types of citizenship, determined by one’s gender, class, and political affiliations, and the exact duties or expectations of a citizen varied throughout the history of the Roman Empire.

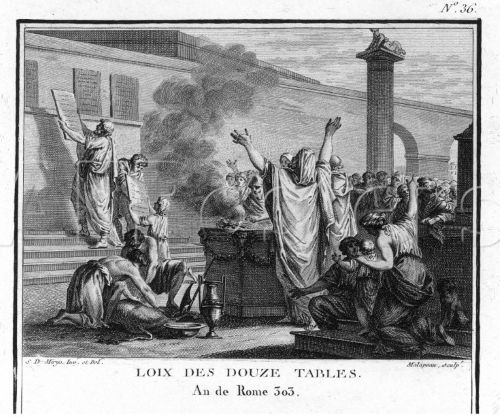

The Twelve Tables

The oldest document currently available that details the rights of citizenship is the Twelve Tables, ratified c. 449 BC.[1] Much of the text of the Tables only exists in fragments, but during the time of Ancient Rome the Tables would be displayed in full in the Roman Forum for all to see. The Tables detail the rights of citizens in dealing with court proceedings, property, inheritance, death, and (in the case of women) public behavior. Under the Roman Republic, the government conducted a census every five years in Rome to keep a record of citizens and their households. As the Roman Empire spread so did the practice of conducting a census.[2]

Roman citizens were expected to perform some duties (munera publica) to the state in order to retain their rights as citizens. Failure to perform citizenship duties could result in the loss of privileges, as seen during the Second Punic War when men who refused military service lost their right to vote and were forced out of their voting tribes.[2] Women were exempt from direct taxation and military service.[3] Anyone living in any province of Rome was required to register with the census. The exact extent of civic duties varied throughout the centuries.

Much of Roman law involving the rights and functions of citizenship revolved around legal precedents. Documents from Roman writer Valerius Maximus indicate that Roman women were in later centuries able to mingle freely about the Forum and to bring in concerns on their own volition, providing they acted in a manner that was becoming of their family and station.[3]

Much of our basis for understanding Roman law comes from the Digest of Emperor Justinian.[4] The Digest contained court rulings by juries and their interpretations of Roman law and preserved the writings of Roman legal authors.

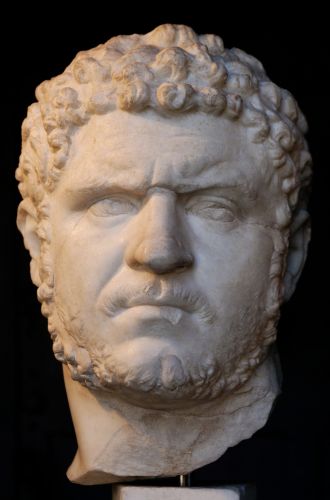

The Edict of Caracalla

The Edict of Caracalla (officially the Constitutio Antoniniana in Latin: “Constitution [or Edict] of Antoninus”) was an edict issued in AD 212 by the Roman Emperor Caracalla, which declared that all free men in the Roman Empire were to be given full Roman citizenship and all free women in the Empire were given the same rights as Roman women, with the exception of the dediticii, people who had become subject to Rome through surrender in war, and freed slaves. Before the edict of Caracalla generalized Roman citizenship to many provinces of the empire, civitas (Roman citizenship) was very exclused and it was first extended a significant number of inhabitants of the Province of Africa Preconsularis and Numidia, they were given Roman citizenship following the Punic Wars, such as the case of Iomnium and others[5]

By the century previous to Caracalla, Roman citizenship had already lost much of its exclusiveness and become more available between the inhabitants throughout the different provinces of the Roman Empire and between nobles such as kings of client countries. Before the Edict, however, a significant number of provincials were non-Roman citizens and held instead the Latin rights.

The Bible’s Book of Acts indicates that Paul the Apostle was a Roman citizen by birth – though not clearly specifying which class of citizenship – a fact which had considerable bearing on Paul’s career and on the religion of Christianity.

Types of Citizenship

Overview

Citizenship in Rome could be acquired through various means. To be born as a citizen required that both parents be free citizens of Rome.[6] Another method was via the completion of a public service, such as serving in the non-Roman auxiliary forces. Cities could acquire citizenship through the implementation of the Latin law, wherein people of a provincial city of the empire could elect people to public office and therefore give the elected official citizenship.[7]

The legal classes varied over time, however the following classes of legal status existed at various times within the Roman state:

Cives Romani

The cives Romani were full Roman citizens, who enjoyed full legal protection under Roman law. Cives Romani were sub-divided into two classes:

- The non optimo iure who held the ius commercii and ius conubii[a] (rights of property and marriage)

- The optimo iure, who held these rights as well as the ius suffragii and ius honorum (the additional rights to vote and to hold office).

Latini

The Latini were a class of citizens who held the Latin rights (ius Latii), or the rights of ius commercii and ius migrationis (the right to migrate), but not the ius conubii. The term Latini originally referred to the Latins, citizens of the Latin League who came under Roman control at the close of the Latin War, but eventually became a legal description rather than a national or ethnic one. The Latin rights status could be assigned to different classes of citizens, such as freedmen, cives Romani convicted of crime, or colonial settlers.

Socii

Under Roman law, citizens of another state that was allied to Rome via treaty were assigned the status of socii. Socii (also known as foederati) could obtain certain legal rights of under Roman law in exchange for agreed upon levels of military service, i.e., the Roman magistrates had the right to levy soldier from such states into the Roman legions. However, foederati states that had at one time been conquered by Rome were exempt from payment of tribute to Rome due to their treaty status.

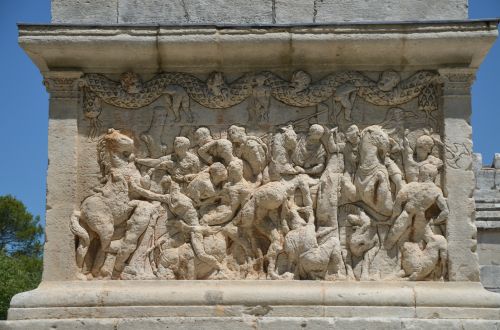

Growing dissatisfaction with the rights afforded to the socii and with the growing manpower demands of the legions (due to the protracted Jugurthine War and the Cimbrian War) led eventually to the Social War of 91–87 BC in which the Italian allies revolted against Rome.

The Lex Julia (in full the Lex Iulia de Civitate Latinis Danda), passed in 90 BC, granted the rights of the cives Romani to all Latini and socii states that had not participated in the Social War, or who were willing to cease hostilities immediately. This was extended to all the Italian socii states when the war ended (except for Gallia Cisalpina), effectively eliminating socii and Latini as legal and citizenship definitions.

Provinciales

Provinciales were those people who fell under Roman influence, or control, but who lacked even the rights of the foederati, essentially having only the rights of the ius gentium (rules and laws common to nations under Rome’s rule).

Peregrini

A peregrinus (plural peregrini) was originally any person who was not a full Roman citizen, that is someone who was not a member of the cives Romani. With the expansion of Roman law to include more gradations of legal status, this term became less used, but the term peregrini included those of the Latini, socii, and provinciales, as well as those subjects of foreign states.

Citizenship for Different Social Classes

Individuals belonging to a specific social class in Rome had modified versions of citizenship.

- Roman women had a limited form of citizenship. They were not allowed to vote or stand for civil or public office. The rich might participate in public life by funding building projects or sponsoring religious ceremonies and other events. Women had the right to own property, to engage in business, and to obtain a divorce, but their legal rights varied over time. Marriages were an important form of political alliance during the Republic. Roman women mostly remained under the guardianship of their father (pater familias) or their closest male agnate.[4]

- Client state citizens and allies (socii) of Rome could receive a limited form of Roman citizenship such as the Latin rights. Such citizens could not vote or be elected in Roman elections.

- Freedmen were former slaves who had gained their freedom. They were not automatically given citizenship and lacked some privileges such as running for executive magistracies. The children of freedmen and women were born as free citizens; for example, the father of the poet Horace was a freedman.

- Slaves were considered property and lacked legal personhood. Over time, they acquired a few protections under Roman law. Some slaves were freed by manumission for services rendered, or through a testamentary provision when their master died. Once free, they faced few barriers, beyond normal social stigma, to participating in Roman society. The principle that a person could become a citizen by law rather than birth was enshrined in Roman mythology; when Romulus defeated the Sabines in battle, he promised the war captives that were in Rome they could become citizens.

Rights

Roman citizens enjoyed a variety of specific privileges within Roman society. Male citizens had the rights to vote (ius suffragi) and hold civic office (ius honorum, only available to the aristocracy).[6] They also possessed ius vitae necisque, “the right of life and death.” The male head of a Roman family (pater familias) had the right to legally execute any of his children at any age, although it appears that this was mostly reserved in deciding to raise newborn children.[4]

More general rights included: the rights to property (ius census), to enter into contracts (ius commercii), ius provocationis, the right to appeal court decisions,[6] the right to sue and to be sued, to have a legal trial, and the right of immunity from some taxes and other legal obligations, especially local rules and regulations.

With regards to the Roman family, Roman citizens possessed the right of ius conubii, defined as the right to a lawful marriage in which children from the union would also be Roman citizens. Earlier Roman sources indicate that Roman women could forfeit their individual rights as citizens when entering into a manus marriage. In a manus marriage, a woman would lose any properties or possessions she owned herself and they would be given to her husband, or his pater familias. Manus marriages had largely stopped by the time of Augustus and women instead remained under the protection of their pater familias. Upon his death, both the men and women under the protection of the pater familias would be considered sui iuris and be legally independent, able to inherit and own property without the approval of their pater familias.[4] Roman woman however would enter into a tutela, or guardianship. A woman’s tutor functioned similarly to a pater familias, but he did not control the property or possessions of a woman and was generally only needed to give his permission when a woman wanted to perform certain legal actions, such as freeing her slaves.[4]

Officially, one required Roman citizenship status to enroll in the Roman legions, but this requirement was sometimes overlooked and exceptions could be made. Citizen soldiers could be beaten by the centurions and senior officers for reasons related to discipline. Non-citizens joined the Auxilia and gained citizenship through service.

Following the early 2nd-century BC Porcian Laws, a Roman citizen could not be tortured or whipped and could commute sentences of death to voluntary exile, unless he was found guilty of treason. If accused of treason, a Roman citizen had the right to be tried in Rome, and even if sentenced to death, no Roman citizen could be sentenced to crucifixion.

Ius gentium was the legal recognition, developed in the 3rd century BC, of the growing international scope of Roman affairs, and the need for Roman law to deal with situations between Roman citizens and foreign persons. The ius gentium was therefore a Roman legal codification of the widely accepted international law of the time, and was based on the highly developed commercial law of the Greek city-states and of other maritime powers. The rights afforded by the ius gentium were considered to be held by all persons; it is thus a concept of human rights rather than rights attached to citizenship.

Ius migrationis was the right to preserve one’s level of citizenship upon relocation to a polis of comparable status. For example, members of the cives Romani maintained their full civitas when they migrated to a Roman colony with full rights under the law: a colonia civium Romanorum. Latins also had this right, and maintained their ius Latii if they relocated to a different Latin state or Latin colony (Latina colonia). This right did not preserve one’s level of citizenship should one relocate to a colony of lesser legal status; full Roman citizens relocating to a Latina colonia were reduced to the level of the ius Latii, and such a migration and reduction in status had to be a voluntary act.

Romanization and Citizenship

Overview

Roman citizenship was also used as a tool of foreign policy and control. Colonies and political allies would be granted a “minor” form of Roman citizenship, there being several graduated levels of citizenship and legal rights (the Latin rights was one of them). The promise of improved status within the Roman “sphere of influence” and the rivalry with one’s neighbours for status, kept the focus of many of Rome’s neighbours and allies centered on the status quo of Roman culture, rather than trying to subvert or overthrow Rome’s influence.

The granting of citizenship to allies and the conquered was a vital step in the process of Romanization. This step was one of the most effective political tools and (at that point in history) original political ideas.

Previously, Alexander the Great had tried to “mingle” his Greeks with the Persians, Egyptians, Syrians, etc. in order to assimilate the people of the conquered Persian Empire, but after his death this policy was largely ignored by his successors.

The idea was not to assimilate, but to turn a defeated and potentially rebellious enemy (or their sons) into Roman citizens. Instead of having to wait for the unavoidable revolt of a conquered people (a tribe or a city-state) like Sparta and the conquered Helots, Rome tried to make those under its rule feel that they had a stake in the system.[7] The ability of non-Roman born individuals to gain Roman citizenship also provided increased stability for those under Roman rule, and the system of sub-division within the different types of citizenship allowed for Roman rulers to work cooperatively with local elites in the provinces.[7]

Romanitas, Roman Nationalism, and Its Extinction

With the settlement of Romanization and the passing of generations, a new unifying feeling began to emerge within Roman territory, the Romanitas or “Roman way of life”, the once tribal feeling that had divided Europe began to disappear (although never completely) and blend in with the new wedge patriotism imported from Rome with which to be able to ascend at all levels.

The Romanitas, Romanity or Romanism would last until the last years of unity of the pars occidentalis, a moment in which the old tribalisms and the proto-feudalism of Celtic origins, until then dormant, would re-emerge, mixing with the new ethnic groups of Germanic origin. This being observed in the writings of Gregory of Tours, who does not use the dichotomy Gallo-Roman-Frankish, but uses the name of each of the gens of that time existing in Gaul (arverni, turoni, lemovici, turnacenses, bituriges, franci, etc.), considering himself a Arverni and not a Gallo-Roman; being the relations between the natives and the Franks seen not as Romans against barbarians, as is popularly believed, but as in the case of Gregory, a relationship of coexistence between Arverni and Franks (Franci) as equals.

It must also be remembered that Clovis I was born in Gaul, so according to the Edict of Caracalla that made him a Roman citizen by birth, in addition to being recognized by the emperor Anastasius I Dicorus as consul of Gaul, so his position of power was reinforced, in addition to being considered by his Gallo-Roman subjects as a legitimate viceroy of Rome; understanding that the Romanitas did not disappear in such an abrupt way, observed its effects centuries later with Charlemagne and the Translatio imperii.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Pharr, Clyde; Johnson, Allan Chester; Coleman-Norton, Paul Robinson; Bourne, Frank Carde. “Ancient Roman statutes : translation, with introduction, commentary, glossary, and index”. avalon.law.yale.edu. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- Dolganov, Anna (2021). “Documenting Roman Citizenship”. In Ando, C.; Lavan, M. (eds.). Imperial and Local Citizenship in the Long Second Century. Oxford University Press. pp. 185–228.

- Chatelard, Aude; Stevens, Anne (2016). “Women as legal minors and their citizenship in Republican Rome”. Clio. Women, Gender, History (43): 24–47.

- Evans., Grubbs, Judith (2002). Women and the law in the Roman empire : a sourcebook on marriage, divorce and widowhood. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- KASTER, ROBERT A. (1 September 2023). Guardians of Language. University of California Press. pp. 352 & 466.

- Chatelard, Aude; Stevens, Anne (2016). “Women as legal minors and their citizenship in Republican Rome”. Clio. Women, Gender, History (43): 24–47.

- Martin, Jochen (1995). “The Roman Empire: Domination and Integration”. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE) / Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswissenschaft. 151 (4): 714–724.

- “Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, C , contŭbernālis , cōnūbĭum”. www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

Further Reading

- Atkins, Jed W. 2018. Roman Political Thought. Key Themes in Ancient History. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Cecchet, Lucia and Anna Busetto, eds. 2017. Citizens in the Graeco-Roman World: Aspects of Citizenship from the Archaic Period to AD 212. Mnemosyne Supplements, 407. Leiden; Boston: Brill.

- Gardner, Jane. 1993. Being a Roman Citizen. London: Routledge.

- Howarth, Randal S. 2006. The Origins of Roman Citizenship. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press.

- Nicolet, Claude. 1980. The World of the Citizen In Republican Rome. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Renz, Annemarie. 2023. Civitas Romana. Das Römische Bürgerrecht und die Römischen Bürgerrechte von 500 v. Chr. bis 500 n. Chr. [Civitas Romana. Roman civil law and Roman civil rights from 500 BC to 500 AD]. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Originally published by Wikipedia, 10.03.2004, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.