Probing beneath the surface of this “world of town-dwellers” and examining its economic underpinning.

By Dr. Anthony M. Snodgrass

Emeritus Laurence Professor of Classical Archaeology

University of Cambridge

“The Mediterranean world is a world of town-dwellers”—these were the magisterial opening words of R. G. Collingwood’s chapter on towns, in the then standard work on Roman Britain, nearly fifty years ago[1] It is one of those epigrammatic statements whose truth content is so high that it would be pedantic to quarrel over details. It must also serve as the main justification for a state of affairs long taken for granted: the corresponding urban bias of classical archaeology. The history of excavation in Greece has been a story of the unearthing of cities and towns, of the sanctuaries that in most cases lay within them, and of the graves and cemeteries that belonged to them. This tradition could therefore be justified in terms of historical reality, as well as by pointing to the rewards it has brought. It could also be justified in historiographical terms: to judge from the ancient sources, almost everything worth recording, except for the campaigns and battles, happened in the cities, in their political meeting places, their law courts, their sanctuaries, their markets. To anyone sharing the assumption that what is the business of ancient history is also the business of classical archaeology, it would have followed, until recent years, that archaeological fieldwork in Greece must be primarily, if not almost entirely, directed towards urban sites.

The study of ancient history in our own generation has concerned itself with a wider range of subjects than those that interested the ancient writers; and some of these wider topics involve the study of rural, at least as much as of urban, life. Agriculture and animal husbandry most obviously exemplify this, and the longer-established study of land ownership has an equally clear application to the rural sector; slavery, technology, and demography also have their rural aspects.

Furthermore, not even the most traditionally minded classical archaeologist will maintain that ancient historical texts are the only ones that concern him. There are also the ancient geographers, and beyond them the whole field of literature sensu stricto , into which rural life makes persistent, if usually brief, obtrusions. We may take a random example from the opening sentence of a Platonic dialogue: “Have you just come back from the fields, Terpsion, or have you been back a long time?”[2] We note that no third alternative is entertained as a possibility, and we are thus reminded that there is a life going on outside the city walls; only that life has little or no “history” in the conventional sense. Finally, excavation is not the only kind of fieldwork open to the archaeologist in Greece and, even if it were, I could conjure up again the ghost of Wilhelm Dörpfeld tirelessly turning over the soil of the Nidri Plain on Leukas, well away from any documented ancient site (though such laborious methods are neither feasible nor perhaps desirable today).

These are all reasons why the modern archaeologist of Greece, even if he takes a more traditional view than I do of the relationship between archaeology and history, might think of turning his attention to the rural landscape of Greece in antiquity. But, on the same hypothesis, he may not find so convincing the further argument that will form the main burden of this article: namely, that a strong incentive to examining rural ancient Greece is the very fact that our ancient sources do not display much interest in it. Some may question this last claim; others may contest the argument drawn from it; but the claim itself has first to be established.

Let me first make two exclusions so as to be clear as to what this claim does not embody. I am not speaking of any lack of response to the beauty of rural scenery: although a case could be maintained at length here, it is not part of my present purpose. Nor am I referring to any dearth of information on the technical practices of agriculture. For the ancient world as a whole, Latin writers more than make amends in both these areas for any earlier deficiencies on the part of Greek authors. I am concerned rather with questions about the nature of the ancient rural landscape of Greece: what did it look like, what was its condition in environmental terms, how far was it diversified, how far was it inhabited, and what went on there besides farming? What, in short, can we establish about the economic geography of rural Greece?

There is one empirical argument that can be advanced in support of the view that the ancient writers leave us very much in the dark on such matters. It is to cast our minds back to the days when the ancient writers formed virtually the only source of knowledge about rural Greece, ancient or modern. In these days of color photography and relatively easy foreign travel, it may require some effort for us to put ourselves in the position of our predecessors in classical studies, though it should not be too difficult for older readers, particularly those who lacked imaginative or well-traveled teachers, to cast their minds back to their childhoods. Today, most of us can mentally set any reference to the Greek landscape in the context of some sort of picture, at first or second hand, of that landscape as it is today. But of course this was not always so, and if we look back to the age of the Enlightenment, or of the Romantic movement, we can read in the pages of a Keats or a Hölderlin an image in words of the Greek landscape that was derived entirely from readings in ancient authors and contemporary expositions of them. However we allocate the responsibility for it, we must all agree that that image was a profoundly mistaken one.

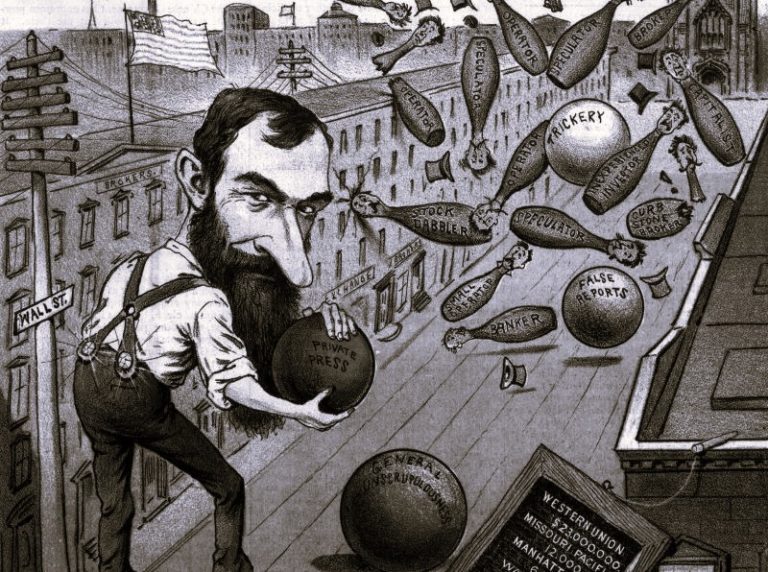

I am, of course, speaking from the standpoint of a northern European, and, as we shall see, this may be an important consideration. In dealing with the important question of how far the landscape of rural Greece today corresponds with that of antiquity, for example, the botanist Oliver Rackham describes a strand of thought that “arises from Western schoolboys and artists being educated in Classical literature, the setting of which is, unconsciously, transferred to the landscape of their own countries. The French or English visitor . . . expects to see heroes spearing the boar in noble forests and nymphs swimming in crystal fountains; finding instead the tangled prickly-oaks and trickling springs of the real Greece, he infers that the land has gone to the bad since Classical times.”[3] The last phrase shows how this delusion has become a serious matter; but first we must acknowledge the truth of Rackham’s previous point. That northern Europeans used to envisage the landscape of Greece in terms of that of their own countries can be shown, for example, by the green hills of Calauria and the dripping woods of elm and willow on Tenos traversed by Hölderlin’s Hyperion;[4] or by the somewhat absurd environmental settings given by Victorian painters to their classical subjects—as in Waterhouse’s Hylas (Figure 1), in which every detail would be more appropriate to southern England than to Greece.[5] Everyone will agree that such scenes are a travesty of the landscape of Greece as it is now . But what of the claim, less easily falsifiable, that it was once, in classical times, much more like this?

This view is a more widespread, respectable, and durable one. Although Rackham advances some substantial arguments for rejecting it, his main conclusion, that the degree of forestation in classical Greece was no greater than today, must rank as unorthodox even in 1983. The traditional view he criticizes derives some of its authority from a famous passage in the Critias (111b-c) in which Plato not merely describes the deforestation of Attica in earlier times, but actually spells out some of the accompaniments, such as the loss of rainfall. As Rackham observes, however, the meaning of this passage has been distorted. Plato has been called as a witness for a well-known ecological phenomenon: deforestation leading to erosion on the hill slopes, with all the ulterior consequences of that. What he actually describes is the reverse sequence, an inexorable and apparently natural denudation or erosion of the mountain soils of Attica, which in turn caused deforestation by loosening the tree roots. By ignoring a vital distinction between man-made and natural agencies, scholars have built up a largely theoretical jeremiad of cumulative degradation of the environment. “They have too easily supposed that a succession of builders of triremes, insouciant shepherds, marauding armies, Turkish maladministrators, and rapacious woodcutters—some of whom might otherwise be expected to undo the damage done by others—have reinforced one another and each contributed to a progressive decline.”[6] This, Rackham shows, is an improbable reconstruction, presupposing as it does a single-minded and uninterrupted process of destruction and making no allowance for the compensating processes of nature.

Plato’s words in the Critias , on the contrary, show primarily that, for a thoughtful Athenian of the fourth century B.C. constructing a mythical, not literal, account of his country’s prehistory, it was already reasonable to describe the landscape of Attica as resembling “the wasted skeleton of a sick man.” In other words, at a point only a quarter of the way through the life of the historical Greco-Roman culture, Plato’s readers could already recognize the treeless and stony bareness that many modern writers have first deplored and then blamed on the destructive activity of unenlightened (which means primarily post-classical) mankind. I find it easier to follow Rackham’s view, at least in the aspect of vegetation cover to which it mainly refers: that we should assume the rural landscape of ancient Greece to have resembled, in environmental terms, that of Greece today.

The reader who is prepared to share this assumption can then turn once again to classical literature and, if he looks widely and closely enough, find many features that will not be unfamiliar. A first point that emerges clearly is that the rural landscape, as today, was differentiated—one might say graded. The commonest distinction in the sources is between the oikoumene and the eskhata : between the part of the landscape where people lived, or at least worked, and the other region that existed not only all round the frontiers of Greece itself, but, on a microcosmic scale, round the territory of many individual Greek states—the sector devoted to hunting and pastoralism, warfare, and the training and initiation of the adolescent males. We are also given the impression, though less clearly, that this grading of the landscape was somehow less sharp than what we are used to in the wilder parts of northern Europe and North America. Even the eskhata were regularly, if sporadically, used for warfare and other purposes. In ancient as in modern Greece, little if any of the homeland was regarded as a total wilderness. With North America there is, of course, an enormous difference of scale, but this is not true of an area like the Highlands of Scotland. I doubt very much whether there was or is anywhere in Greece where the same thing could happen as occurred forty years ago in Sutherland: during World War II, a military airplane went missing and the searchers, entering the area where it was last reported, found a crashed plane dating from World War I, which had not been seen by anyone in the intervening thirty years. In Greece, one finds the traces of man (including ancient man) almost wherever one goes. For instance, the rocky cliff path that runs round the headland between Aigosthena and Kreusis on the Corinthian gulf, so precipitous that the guerrillas in World War II could, with a modest expenditure of gelignite, close it altogether for long periods, was used by sizeable armies in antiquity, including, on more than one occasion, the marches of King Kleombrotos before he led the last great Spartan army to defeat at Leuktra.

Then there is the question of the pattern of rural landholding. Let us focus for a moment on an image used by Sophokles near the beginning of the Women of Trachis . Deianeira, the wife of Herakles, is complaining that her husband’s questing life-style keeps him away from home for long periods. She waits anxiously for his return, and he hardly ever sees his children: “Like a farmer who has taken a distant field into cultivation, and sees it only just when sowing and harvesting” (32–33).

This image must have been at least as vivid for Sophokles’ audience as it is for us—more so, if we live in more northerly climes, since it describes a kind of farming not normally possible there. Sophokles was himself a landowner and (even if the play was actually produced after the Archidamian War had broken out, as is possible) probably three-quarters of the audience had firsthand experience of agriculture themselves. To this day, one can see pieces of marginal land in Greece that look as if they have been treated in the way this image describes, and some kind of crop still comes up; whereas away from the Mediterranean, there are always activities (winter plowing, fertilizing, weeding) that need to take place at periods other than seedtime and harvest. Thus even a dramatic poet can conjure up a glimpse of rural life.

But there is one further piece of information that may be squeezed out of this Sophokles passage, brief though it is. It seems to me to give the clear impression that the outlying field is at some distance from the farmer’s other land. Now, one of the constants all modern anthropological, economic, and juristic studies of Greece take almost for granted is the system of land-ownership. A given farmer’s landholdings are likely to be a number of small plots widely scattered over the landscape (Figure 2). Inasmuch as this is the direct result of the modern Greek system of partible inheritance, and inasmuch as there is clear evidence of the existence of a similar system in large areas of ancient Greece, it would seem to follow that an ancient Greek farmer, too, had to cope with this extraordinarily inconvenient circumstance. Most ancient written sources, assuming their readers’ familiarity with such matters, tell us relatively little about this in direct words, though there are inferences to be drawn from the Attic orators, for example. It is therefore valuable to find Sophokles implying the existence of such a system in fifth-century Athens.

But this interpretation of a poetic metaphor may already seem too literal-minded to some readers, so I shall turn instead to the place where we might naturally look first for full descriptions of the rural landscape: that is, to what might loosely be termed the geographers. I do so with hesitation, because there are many who know more than I about such writers, and I am also conscious of following, in fairly close succession, the learned Sather Lectures of Christian Habicht on Pausanias.[7] I have in the past six years had intensive experience of at least one region of rural Greece, Boeotia, in the course of carrying out an archaeological survey there, and this has involved the study of the ancient geographical texts. It is in fact on the ancient landscape of Boeotia (Figure 3) that I shall concentrate, beginning with the fullest surviving ancient treatment of it, the ninth book of Pausanias’s Description of Greece, written in the third quarter of the second century of the Christian era.

Let me try to anticipate one criticism by saying that, whatever the exact purpose for which Pausanias wrote his book was (and that is not quite so simple a question as it might seem), I fully appreciate that he was not setting out to throw light on the kinds of question that concern us here, so that it is unfair to tax him with omissions in this area. He evidently set out to describe the things most worth seeing in the mainland of Greece for the benefit of the reasonably well informed and intelligent traveler of the Roman imperial period. Most of his readers would doubtless have shared his own presupposition that this meant, almost exclusively, the monuments of Greece’s noble past, rather than of its subdued present; and they would quite certainly have shared his further assumption that the most interesting sights were, by and large, to be found in and around the cities. Pausanias does not, in any case, ignore the landscape outside the cities: on the contrary, he has a definite eye for certain kinds of natural feature. But I shall still argue that, for him, the rural landscape is largely a kind of void that intervenes between each city or sanctuary and its nearest neighbor; a void crossed by the lifeline of the road system (doubtless much improved under Roman rule), which enabled the traveler to pursue a linear course from starting point to destination, with little regard for the lateral and vertical dimensions. But, as often, it is better to exemplify than to generalize.

Let us see how Pausanias conducts his reader through Boeotia. He has already explained in his account of Attica (1.38.8) that Mount Kithaeron was “the border of Boeotia,” and he takes this up at 9.2.1, where he speaks of part of Kithaeron (the northern slopes, we are left to infer) being “Plataean ground.” He gives, in passing, an interesting glimpse of the agricultural practices of the Plataeans, though in the context of the years round 373 B.C. (9.1.3): in their justified suspicion of the Thebans, the Plataeans at this period did not venture out into their more outlying fields unless they had reason to think that a political assembly was being held in Thebes, which would occupy the attention of the Theban citizen army. This same historical narrative gives him occasion to mention that there were two alternative roads, one more direct than the other, from Plataea to Thebes, and presently he will himself introduce us to both of them (9.2.1, 3). Before even entering Plataea, he makes a first detour to Hysiai and Erythrai, and then characteristically retraces his steps. Each feature that he mentions is related to the road he is following (“on your right as you turn off”; “on your right on the way back”). There follows his description of Plataea, and then, at 9.4.4, we are on our way again. Our destination is Thebes, but it is not made clear (and the omission has cost gallons of modern ink) whether Pausanias’s mention of the spring Gargaphia, in the immediately preceding sentence, implies that it lay on or near this road (the spring had been one of the main landmarks in the famous battle of 479 B.C.).

As we follow Pausanias to Thebes, it is helpful to know that, in Boeotia as elsewhere in ancient Greece, many place-names were held to derive from the names of mythical personalities: thus, Plataea from the nymph Plataia, a daughter of the king Asopos who gave his name to a river, and who was supposed to have been a successor of a king Kithaeron who gave his name to the mountain, and so on. All this Pausanias faithfully reports (9.1.2). But consider his description of the next stage of the road:

On the way from Plataea to Thebes is the river Oeroë they say Oeroë was a daughter of Asopos. Before you cross the Asopos, if you turn downstream for forty stades [i.e., about eight kilometers], you come to the ruins of Skolos. . . . To this day, the river Asopos divides the territory of Plataea from that of Thebes.

Note that we are not given an overall distance (though we are told the length of the detour to Skolos). Pausanias makes it clear enough that you come to the river Oeroë before the river Asopos, but the careless reader might well take his story of the relationship between their two eponyms to imply that the former river is a tributary of the latter. This is not so: one flows westwards and the other eastwards. As for the Skolos detour, it has generated a long debate as to whether this sentence allows, or excludes, the possibility of Skolos itself, though reached by turning down the near bank of the river, lying on the far (i.e, northern) bank. In some opinions the likeliest site for Skolos, at the right distance from the main road, lies on the north bank.[8] This is one of the many topographical disputes arising from the fact that one cannot be sure that Pausanias has mentioned every significant detail; though as a matter of fact, any sort of firsthand familiarity with the Greek landscape, such as would give one a true picture of the small size and volume of such rivers as the Asopos, might lead one to doubt whether the crossing of such a stream would constitute a “significant” step.

It may seem less than just to contrast Pausanias with a man who has been called “the prince of travelers,” but a comparison of his account with that of William Martin Leake, who traversed the same road rather more than sixteen centuries later, will bring out some of what I miss in the former. Leake leaves Plataea with an initial detour in the opposite (i.e., southern) direction:

Dec. 29, 1805. From the upper angle of the ruins [i.e., of Plataea] I ride in twenty-three minutes, preceded by a man on foot, over the rocky slope of Cithaeron to the fountain Vergutiani, and thence ascend in five minutes to a projecting rock now serving as a shelter for cattle, in the middle of a natural theatre of rocks at the head of the verdant slope above the fountain. . . . Having descended from the fountain into the road which leads from Kokkla eastwards to the villages along the mountain side, I cross the branch of the Oeroë which, coming from Thebes, I called the first, and eight minutes further a hollow, the waters of which form a branch of the Asopus; its upper extremity is very near the sources of the easternmost branch of the Oeroë. Here, therefore, is exactly the partition of the waters flowing on the one side to the sea of Euboea, on the other to the Corinthiac Gulf.[9]

Notice how Leake first of all sets the season for his journey, an important detail for all questions of the level of lakes, the flow rate of rivers, the snow line, and so forth. Notice his use of orientation. Notice how phrases like “the verdant slope” or “a shelter for cattle” evoke both the landscape and its uses, besides making it easy for us to follow in his tracks. Notice his unwavering precision over journey times, making it possible to calculate distances. Notice finally how clearly he settles the matter of the direction of flow of the two rivers that arose in connection with Pausanias.

Despite obvious differences of purpose and background, there are many similarities between Pausanias and Leake. Both describe Greece primarily in terms of the traces of earlier periods; both do so with learning and honesty, and in a way that often makes us want to follow in their footsteps. Above all, both are supremely self-effacing: Pausanias would no more think of inserting into his account of the battle of Plataea the fact that he himself bore the same name as the victorious commander than Leake would of mentioning the day—presumably some time during the month of November 1805—when he received news of the battle of Trafalgar (although it had a certain relevance to his mission, which was to carry out a confidential survey of the geography of Greece, partly with a view to defending it against the French if the clash between the two powers spread there). The little that we know of Pausanias himself emerges entirely from a few casual hints dropped in the text of his book, and it is not much exceeded by what Leake reveals of his own views in his work. Finally, both men timed their journeys outstandingly well, Pausanias for the description of standing buildings that were soon to collapse, Leake for the detection of their remains before many of these were to vanish too.

But, from the excerpts that we have seen, it is the differences of approach that emerge more conspicuously. Leake, partly because of his mission, is more interested than Pausanias in the Greece of his own day; and he is perhaps typically British in relishing, or at least taking an interest in, the rural scene. But my motive for setting up the comparison between Pausanias and Leake is really to show that there is a possible alternative to the former’s approach; and that the outlook and interests of a Pausanias need not be regarded as permanently binding upon the archaeologist of Greece.

We do not need to follow Pausanias’s description of Boeotia sentence by sentence: much of the essential information can be conveyed by means of a map (Figure 4) containing only such information as he gives in his account, though incorporating one or two necessary principles, such as that of including the approximate compass directions, which are absent from his pages. In chapter 8 he at last enters Thebes, which he will use as the center for his three subsequent excursions into the Boeotian territory. Ten chapters are occupied with the description of the city itself. Then he embarks on the first excursion, which turns out to take us roughly northeastwards to the shore of the Euripos opposite Euboea, and occupies chapters 18 to 22 inclusive. The black circular symbols mark the towns (or more often the ruins of towns) that he passes through; black conical symbols are mountains, gray conical symbols rivers, with their direction of flow (also usually omitted by him); the sea, where he touches it, and the portions of lakes that he mentions, are shown by the gray areas, while dotted lines mark the few cases where he mentions territorial boundaries. Distance figures are intermittent, and the fragmentary appearance of the map as a whole reflects the virtual absence of lateral cross-references: for instance, in saying whether the coast reached on one journey is the same one as that reached at a different point on an earlier or later journey. On the first, eastward excursion, the omission of a distance figure has again led to difficulty in locating a site, Teumessos (Te). A little further on, at Mykalessos (My), there is a curious crux raised by Pausanias’s reference to a sanctuary of Demeter “by the sea of [or at] Mykalessos,” when other evidence makes it impossible to believe that Mykalessos was on the coast.[10] The fault here (if such it can be called) lies in a failure to distinguish between a town itself and an outlying part of its former territory.

The second excursion occupies but two chapters (23 and 24), and starts from the same gate of Thebes, on its eastern side. Yet, though Thebes was fabled for its possession of seven gates, we prove to be going in a quite different direction, rather west of north, to reach the Euripos again at two places, Larymna and Halai. As before, Pausanias makes detours but always retraces his steps to the main route of the excursion. The journey has the interest of including a boat crossing of an arm of Lake Kopais, between Akraiphnion and Kopai: here above all we would welcome an indication of the season of the journey, since it is unlikely that this area was more than seasonally covered by the lake in the second century A.D. One may remark on (some indeed have deplored) Pausanias’s omission of any mention of the Mycenaean fortress of Gla, and a further difficulty arises when Pausanias gives distance figures between two pairs of towns—eleven stades from Kopai to Olmones, seven from Olmones to Hyettos—which are improbably small, the second being well under a mile. Since the first and third of these places are definitely located, we can in fact state that either a textual corruption or a thoughtless error has occurred.[11]

The third and last excursion, which takes Pausanias out of Boeotia and into Phokis, starts from a different gate of Thebes and runs approximately westwards. It is much the longest, covering chapters 25 to 41 inclusive. It differs from its predecessors in its disjointedness: we start in the usual way by going as far as Onchestos, then retracing our steps for part of the way and turning off to Thespiai, the second main tourist attraction in ancient Boeotia. But then there are two abrupt leaps in space: first we jump to Kreusis, “the harbor of the Thespians,” which we learn can be reached from the Peloponnese by an unpleasant zigzag voyage round headlands. We are therefore on the Corinthian Gulf, and no doubt Pausanias visited this part of Boeotia on a separate journey by ship. From Kreusis, we sail westwards to the harbor of Thisbe, visit Thisbe itself, and then proceed to Tipha. This poses the most substantial topographic puzzle in the book: both the harbor of Thisbe and Tipha have been located, and there is no question but that, if sailing westwards, you would come to Tipha before and not after Thisbe.[12] The best explanation lies in the realization that a linear progression like Pausanias’s does not have to be in a straight line: both Tipha and Thisbe lie within a deep bay, and Pausanias’s course must have curved round and doubled back on itself after he entered the bay, although he does not tell us so.

There follows the second leap in space, the most abrupt of all. At 9.32.5 we are suddenly told: “Inland from Thespiai lies Haliartos.” It is more than four chapters since we left Thespiai, but what is more trying is that this move brings us within a bare two miles of a point that we reached even before that (9.26.4)—the sanctuary of Onchestos, which some travelers must have been surprised to find themselves in full view of without having been told of its proximity. From Haliartos, we go westwards to Koroneia and Orchomenos, again passing Lake Kopais, which however is only mentioned because in winter the south wind carries its waters over the territory of Orchomenos. We leave Boeotia by way of the towns of Aspledon, Lebadeia, and Chaeroneia, although in order to visit these places in this order from Orchomenos, one has to pursue a tortuous itinerary that would involve some retracing of steps.

What I hope mainly to have conveyed by this extensive summary of Pausanias’s route through Boeotia is its relentless linearity (the interruptions notwithstanding). His treatment of the landscape is for much of the time in one dimension: each place is further or nearer along the line of the road that he is following; when he makes a detour, he retraces his steps; different roads are not related to each other laterally, and not even three-term relations along a single road (“B is between A and C “) are used. Few if any orientations are given, and changes or reversals of direction are sometimes left for the reader to infer. The image that springs to mind is that of a man crossing a morass on lines of duckboards who does not venture on short cuts. It is interesting to find that Christian Jacob has suggested[13] that Pausanias may have habitually used, not a proper two-dimensional map, but an itinerary of the kind of which one precious example is preserved for us in the Peutinger Table (Figure 5), a thirteenth-century copy of a “world map” of about A.D. 300 that displays almost exactly the same kind of linearity, concentrating on progress forwards to the point where lateral relations become not only neglected but distorted (in Figure 5, for example, the position of Boeotia is at two quite different points along the two separate itineraries that lead to Athens).

I do not dissent from Jacob’s view that Pausanias’s topographical indications are nevertheless, in the main, effective for the traveler who shares his interests, though instances like the silence over the proximity of Onchestos and Haliartos are perhaps exceptions. But in a treatment such as Pausanias’s, the rural landscape cannot really emerge as a two-dimensional space. There are a few signs of interest in the rural scene, mostly directed at natural phenomena (as in the description of Mount Helikon), and on one occasion actually referring to landscape use (in the short but fascinating passage on the flood-control measures taken in the landlocked basin that lies between Thisbe and its harbor). But rural settlement, population, and agriculture are passed over in silence, requiring as they do an awareness of rural space .

To the obvious objection that I have unfairly imposed modern concerns on an ancient writer, and then compounded the offense by comparing him with a modern one, I reply by introducing a quite different comparison, with two earlier writers, Strabo and the author who for long went under the misleading appellation of pseudo-Dikaiarchos. Strabo, like Pausanias a Greek-speaking subject of the Roman Empire from Asia Minor, compiled his Geography over a longish period, beginning nearly two centuries before Pausanias. By comparison with the latter, he starts with one signal disadvantage: whereas no one can dispute the immediacy of some of Pausanias’s firsthand descriptions, “it is not possible to say with certainty whether Strabo ever saw any part of Boeotia”;[14] and similar doubts hang over other sections of his account of the Mediterranean world.

Once we look at Strabo’s Boeotia, however, through the medium of a map (Figure 6) corresponding to the earlier one for Pausanias, we find certain qualities that were missing in the other’s case. Strabo uses orientations; his Boeotia has two continuous coasts, and includes more features and places than are mentioned by Pausanias. The measurements that Strabo gives are not only linear ones along roads, but also cover distances across the sea (as between Boeotia and Euboea), and include a figure for the periphery of Lake Kopais. This last is always the hardest kind of measurement to calculate, and Strabo’s surprisingly high figure may be based on a painstaking coverage of every promontory and inlet: if so, it is the more impressive to find topographical work of this level being undertaken. Towns are given a rough grading according to size and prosperity. Strabo does not, like Pausanias, undertake his journeys radially

ally from Thebes; his purpose is different, even though his own description of what he is doing, periegesis tes choras , precisely recalls Pausanias’s title for his work. Strabo’s original plan is to cover the landscape by treating it as a series of regional groupings of towns and villages; the trouble is that he does not stick to this plan. After an exemplary account of the northeastern seaboard (9.2.6 onwards), he reasonably turns to the inland plains (9.2.15) and describes them. But then (9.2.21) he abruptly switches to using the long entry in the Homeric Catalogue of Ships (Iliad 2.494–516) as the basis of his account. The result is, as Paul Wallace observes, most unfortunate: the sequence of places in Homer is governed more by considerations of meter than by those of topography, and Strabo’s hitherto coherent sequence falls apart.[15] Even so, his account is more continuous than that of Pausanias, and his interest in natural features is deeper and more systematic. What he offers us is, in short, a true physical geography; in this respect, the rural landscape is covered in a degree of detail that roughly corresponds to Pausanias’s much fuller description of the urban scene. In cases where actual autopsy is important to the issue—as with the discrepancy over the disappearance (Strabo 9.2.33) or the survival (Pausanias 9.26.5, at a later date)—of the grove of Poseidon mentioned by Homer at Onchestos, we have good reason to trust Pausanias more. But there is a common negative feature of both accounts: Strabo, even in the first and more systematic part of his description, exhibits no more interest than Pausanias in the landscape as a field for, and in part the product of, human activity. On the economic geography of the countryside, both authors are essentially silent.

But is the whole search for information of this kind misconceived? Is it simply a product of anachronistic modern preconceptions? Surprisingly, perhaps, we are able to give a firm negative answer: there exists a little evidence to show that there were authors and readers in ancient Greece who shared, to some degree, these concerns. It is refreshing to turn to a third account of Boeotia that, although hasty and, in both senses of the word, partial, displays just such interests, and thus fills some of the gaps in Strabo’s and Pausanias’s descriptions. It is hard to believe that a writer whose work was once described by Wilamowitz as being almost without rival in the extant body of Greek literature for its richness of life, should have met with the relative neglect that has been the fate of Herakleides ho kritikos (or possibly ho Kretikos , the Cretan). His three surviving fragments were much discussed in the years between their detailed examination by Müller in Fragmenta Historicorum Graecorum in 1848 and the end of the nineteenth century; but since then there has been little, apart from the monograph Friedrich Pfister devoted to them in 1951.[16] In brief, because the fragments appeared in two manuscripts set among works ascribed to the philosopher Dikaiarchos, their author for years passed under the guise of “pseudo-Dikaiarchos.” It seems to have been F. Osann, in 1831, who first noticed that Apollonius, a Hellenistic writer on marvels, gave an almost verbatim quotation from one of these fragments, and ascribed it to an otherwise quite unknown Herakleides Kritikos. Much study was devoted to the dating of the fragments on their internal evidence: the upshot is that we can place them firmly within the time-span of 275–200 B.C., and more tentatively between c. 260 and 229 (perhaps even between 260 and 251 B.C.). Their author thus antedates Strabo by about the same margin as Strabo does Pausanias. We are concerned here only with fragment 1, an itinerary that proceeds from Athens to Chalkis by way of eastern and central Boeotia.

It is instantly clear that we are in the presence of an individualist and a humorist: quotations, off-the-cuff evaluative judgments (often derogatory), and downright gibes alternate with extremely observant description. Thus, as we set out on the road into Boeotia from Oropos:

From here to Tanagra it is 130 stades. The road runs through a landscape of olive groves and forest, entirely free of any fear of robbers. The town lies on a rocky eminence, with a white, clayey appearance, much beautified by the house porches with their votive pictures in encaustic technique. It is not particularly rich in locally grown produce, but its wine is the best in Boeotia.

This passage is quite typical. When Herakleides arrives at a town, he is mostly interested in describing the character and behavior of the people (particularly the women), often entertainingly. But it is his passages between the towns that are the revelation. Thus, from Tanagra to Plataea, “the road is lonely and stony, stretching out along Kithaeron”; from Plataea to Thebes, it is “smooth and level.” Thebes is placed in its environment: the city is built “on black earth”; “well-watered, green, with deep soil, it has the most gardens of any city in Greece.” These features, he goes on, and the abundance of local produce on sale, make it a pleasant summer resort; but in winter it is windy, snowy, and muddy. From Thebes to Anthedon, the road is “oblique but driveable, running through fields.” Anthedon has trees planted in its marketplace; rich in wine and seafood, it lacks corn because of the poverty of its soil; nearly everyone there is a fisherman, and many build their own boats. As for the land, it is not that the Anthedonians neglect it, but that they simply do not have it.

We could do with a lot more information of this kind. But at this point, to our dismay, our author pronounces: “That is what Boeotia is like. For Thespiai has ambitious menfolk, fine statues, and nothing else” (this last being apparently his apology for omitting to visit a major point of interest in Boeotia). There follows a barrage of devastating anti-Boeotian apophthegms, ending with Pherekrates’ “Keep away from Boeotia if you are wise.” We realize that, besides Thespiai, Herakleides is not going to take us to Koroneia, Orchomenos, or anywhere west of Thebes, and our only consolation is his parting description of the road along the shore from Anthedon to Chalkis, between the wooded, well-watered hills and the sea. The rarity of such description among Greek writers merely sharpens our sense of deprivation.

Such, at least, is my reaction. The existence of this fragmentary work proves that such an approach to the study of rural Greece could exist in antiquity; for even if Herakleides is dismissed as not being a “serious” author, his writings must have interested a certain readership. But more important is the fact that the virtual isolation of the work, in respect of its subject matter, among the surviving ancient sources means that, in pursuing the same approach today, we cannot use these sources as a framework. We shall, to be sure, be able to glean both information and insights from the literature—sometimes, as we have seen already, in rather unexpected places—but these will mostly come in fragmented form; we can, in a somewhat different way, use “universalizing” texts (for Boeotia, Hesiod’s Works and Days is the obvious example) to extract and apply more specific conclusions; but for much of the time, we shall inevitably be on our own.

Today, however, that will hardly constitute an argument against pursuing a line of archaeological enquiry—nor, for that matter, of historical enquiry. The true justification for studying rural ancient Greece is indeed, in a broad sense, historical. Once again, I cite the verdict of an earlier Sather lecturer, Moses Finley, in one of the central conclusions of his The Ancient Economy . Finley found that the view of the ancient city as primarily a center of consumption, founded on the work of Max Weber, was justified. He concluded that the survival of the city accordingly depended on four main variables; first among these was “the amount of local agricultural production, that is, of the produce of the city’s own rural area.”[17] This, to me, is justification enough. The archaeologist who pursues the study of rural Greece, rather than accepting the urban focus of interest of the ancient sources as a kind of datum, will in fact be probing beneath the surface of this “world of town-dwellers,” and examining its economic underpinning.

Endnotes

- In R. G. Collingwood and J. N. L. Myres, Roman Britain and the English Settlements (Oxford, 1936), 186.

- Theaetetus 142a.

- O. Rackham, “Observations on the Historical Ecology of Boeotia,” BSA 78 (1983): 345–46.

- Hyperion, oder Der Eremit in Griechenland (1797–99), ed. J. Schmidt (Frankfurt, 1979), 63 and 16.

- On J. W. Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs , see Richard Jenkyns, The Victorians and Ancient Greece (Oxford, 1980), 190, where he remarks that even the nymphs are “unmistakably English.”

- Rackham, “Observations” (cited in n. 3 above), 346.

- See, now, Christian Habicht, Pausanias’ Guide to Ancient Greece, Sather Classical Lectures, vol. 50 (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1985). I thank Professor Habicht very warmly for his generous loan, during my stay in Berkeley, of the then unpublished typescript of his lectures.

- See W.K. Pritchett, Studies in Ancient Greek Topography , vol. 1 (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1965), 107–9; vol. 2 (1969), 178–80.

- W.M. Leake, Travels in Northern Greece , vol. 2 (1835), 326.

- J. G. Frazer, Pausanias’ Description of Greece , vol. 5 (London, 1898), 66–70, gives what is still the fullest account of this matter.

- See R. Etienne and D. Knoepfler, Hyettos de Béotie et la chronologie des archontes fédéraux entre 250 et 171 avant J.-C. (BCH suppl. 3, 1976), 3–4, 19–29.

- See R. A. Tomlinson and J. M. Fossey, “Ancient Remains on Mt. Mavrovouni, South Boeotia,” BSA 65 (1970): 243–63, with a different explanation for Pausanias’s sequence, 243 n. 2; and on the place in general, E.-L. Schwandner, “Die boötische Hafenstadt Siphai,” AA (1977), 513–51.

- C. Jacob, “Paysages hantés et jardins merveilleux,” L’Ethnographie 76 (1981–82): 41.

- P. Wallace, Strabo’s Description of Boeotia (Heidelberg, 1979), 1; cf. 168–72.

- Ibid., 3.

- F. Pfister, Die Reisebilder des Herakleides , Sitzungsberichte, Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-Historische Klasse, no. 227, vol. 2 (Vienna, 1951), especially 17 (Osann’s identification of the author), 44–48 (his date), and 45 (citation of Wilamowitz).

- The Ancient Economy (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1973), 139.

Chapter three from An Archaeology of Greece: The Present State and Future Scope of a Discipline, by A.M. Snodgrass, published by University of California Press (1987) to the public domain.