Paracelsus’s homunculus straddles the line between science and magic.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

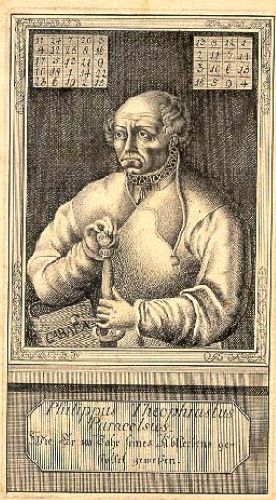

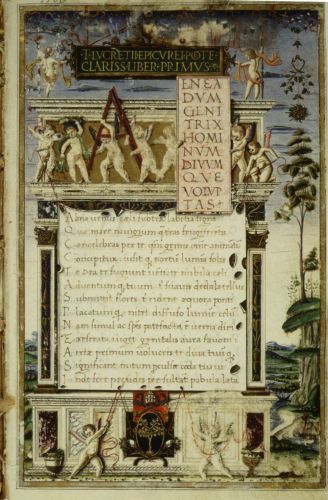

In the medieval and early modern period, the boundaries between science, mysticism, and religion were fluid and permeable. The physician, alchemist, and philosopher Theophrastus von Hohenheim—better known as Paracelsus (1493–1541)—embodied this synthesis. Rejecting the Galenic traditions dominant in contemporary medicine, Paracelsus sought to merge empirical observation with spiritual insight. His work De Natura Rerum (Of the Nature of Things), a series of treatises first printed in the late sixteenth century, epitomizes this endeavor. Among its most intriguing and controversial passages is a procedure Paracelsus claims can fabricate an “artificial man”—a homunculus. This essay explores that procedure in its historical, philosophical, and symbolic context, arguing that Paracelsus’s artificial man should be understood not only as a speculative alchemical product, but also as an expression of a broader vision in which man, nature, and the divine are intrinsically interwoven.

Paracelsus and the Alchemical Tradition

Paracelsus was a pivotal figure in the intellectual transformation of early modern Europe. Trained in both scholastic and folk medical traditions, he developed a unique philosophy that rejected the orthodox Galenic medicine of his time and embraced a radical vision of healing rooted in alchemical principles. Paracelsus’s understanding of nature, disease, and the human body was grounded in the belief that the universe was a living organism permeated by divine intelligence. He maintained that health was the harmonious balance of substances within the body and that disease was the result of chemical imbalances or external spiritual forces rather than humoral disorders.1 By combining his observations as a practicing physician with his mystical and theological convictions, Paracelsus helped to forge a new paradigm in which medicine, chemistry, and spiritual philosophy were inseparable. His work laid the foundation for what would become the “chemical philosophy,” a crucial forerunner to modern scientific thought.

Paracelsus’s contributions must be understood within the broader context of Renaissance alchemy, which was far more than a precursor to modern chemistry. Alchemy in the early modern period was a multifaceted discipline that merged experimental technique with metaphysical speculation. Rooted in ancient Hermetic, Neoplatonic, and Christian esoteric traditions, Renaissance alchemy pursued the transformation of both matter and the soul.2 Paracelsus was deeply influenced by this lineage but innovated upon it by emphasizing the practical and medical applications of alchemical processes. He proposed that the same forces responsible for transforming base metals into gold could be used to purify the human body and restore health. His famous concept of the tria prima—salt, sulfur, and mercury—was a reinterpretation of traditional alchemical elements, reflecting his belief that all substances and diseases had a chemical essence that could be discovered and manipulated.3 This shift from purely symbolic or speculative alchemy to one with therapeutic and empirical goals distinguished Paracelsus from many of his predecessors and contemporaries.

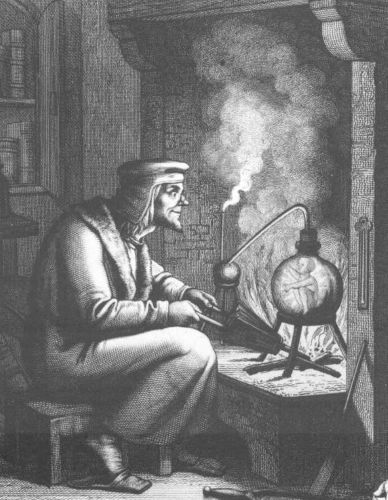

One of Paracelsus’s key innovations was his redefinition of the role of the alchemist. Rather than serving solely as a philosophical sage or metallurgical technician, the Paracelsian alchemist was a healer, prophet, and interpreter of divine wisdom embedded in nature. He likened the alchemist to Christ himself, acting as a mediator between the celestial and terrestrial realms.4 This elevated the status of the alchemist to a quasi-priestly figure whose labor mirrored divine creation. In this way, Paracelsus saw the alchemical process as both a physical and spiritual transformation—a kind of sacred science. The lapis philosophorum (philosopher’s stone), a central symbol in alchemical lore, was not just a substance that could transmute metals, but also a metaphor for the perfected soul. For Paracelsus, the successful alchemist had to be morally pure and spiritually attuned, for only then could he access the hidden properties of the cosmos.5 This ethical and mystical dimension reinforced the notion that true alchemy was a divine vocation rather than a mechanical or purely intellectual enterprise.

Despite his rejection of scholastic orthodoxy, Paracelsus was not opposed to reason or experimentation. On the contrary, he championed observation and experience over book learning, famously declaring that “the universities do not teach all things” and that the true source of knowledge was nature itself.6 His writings include case studies, chemical recipes, and astrological charts, all of which reflect an effort to systematically understand and manipulate natural processes. Yet this empirical approach was always grounded in a theologically inflected worldview. Nature, for Paracelsus, was a divine book written in symbols, and the task of the alchemist was to decode its language.7 This synthesis of empirical investigation with religious symbolism made Paracelsus a transitional figure between the medieval and modern worlds. His influence can be seen not only in the development of iatrochemistry (chemical medicine) but also in the later works of scientists such as Jan Baptist van Helmont and Robert Boyle, who built upon Paracelsian foundations while distancing themselves from its more mystical elements.

Paracelsus’s legacy within the alchemical tradition is thus complex and multifaceted. He helped shift alchemy from a speculative and often secretive art to a more accessible and practically oriented discipline. At the same time, he infused it with a new sense of spiritual purpose, drawing upon Christian theology, astrology, and esoteric philosophy to articulate a vision of the cosmos as a dynamic interplay of divine forces.8 His texts, often obscure and filled with allegorical language, resisted easy interpretation and were embraced by diverse audiences—from apothecaries and physicians to mystics and occultists. While many of his ideas were marginalized or ridiculed by Enlightenment thinkers, his holistic vision of nature and medicine continues to resonate in contemporary alternative medical and spiritual practices. By blending empirical inquiry with mystical insight, Paracelsus helped redefine the possibilities of human knowledge in an age on the brink of scientific revolution.

The Homunculus Procedure

The most infamous section of De Natura Rerum is Paracelsus’s description of the creation of a homunculus—a miniature human being created without female gestation. He writes:

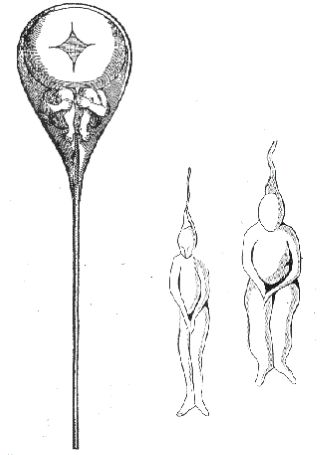

“Let the semen of a man be putrefied by itself in a sealed cucurbit for forty days with the highest degree of putrefaction in a horse’s womb, or at least so long until it begins to live, move, and be agitated, which can easily be seen. After this time, it will look somewhat like a man, but transparent, without a body. If, after this, it be daily nourished and fed, prudently and cautiously, with the arcanum of human blood, and be kept for forty weeks in the perpetual and equal heat of the horse’s womb, it becomes thence a true and living infant, having the same limbs as any child born of a woman, but much smaller.”9

The so-called homunculus procedure stands among the most provocative examples of Renaissance alchemical speculation. In this text, Paracelsus describes a method by which a miniature human being can be artificially generated from human semen, incubated in a sealed glass vessel within a horse’s womb, and nourished with human blood.10 The idea that life could be fabricated through alchemical means without the involvement of a female womb represented a radical departure from traditional notions of reproduction, which were deeply rooted in Aristotelian and Galenic biology. For Paracelsus, this experiment was not merely a curiosity; it was a testament to the belief that man, made in the image of God, could participate in divine creation through mastery of nature’s secret processes. The homunculus, as he described it, was both a symbol of this potential and a speculative entity reflecting the synthesis of mysticism, natural philosophy, and alchemical science.

Paracelsus’s instructions for creating a homunculus are notably detailed and alchemically specific. He prescribes that human semen be sealed in a cucurbit (a distillation flask) and buried in a pile of horse dung for forty days, simulating the natural warmth of the womb. After this incubation period, the material is said to become animated, at which point it should be carefully nourished with the arcanum of human blood for an additional forty weeks.11 These phases mirror the gestational stages of natural embryonic development, suggesting that Paracelsus was attempting an analog to divine generation using controlled alchemical procedures. The reliance on the number forty—frequently appearing in Biblical and mystical literature—reinforces the symbolic dimension of the experiment. The reference to human blood as nourishment alludes to the vitality and sacredness of blood in both Christian and alchemical traditions, where it is often linked to transformation, sacrifice, and life force.12 In effect, the homunculus becomes not just a material product, but a spiritual artifact created through ritualized engagement with nature’s creative energies.

While the procedure may strike modern readers as bizarre or fantastical, it must be contextualized within early modern understandings of reproduction and life. The theory of spontaneous generation—the belief that life could arise from non-living matter—was widely accepted until it was debunked in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.13 Within this framework, the notion that human life could emerge under specific alchemical conditions was not entirely implausible. Paracelsus believed that natural processes could be imitated and accelerated through the art of the alchemist, whose knowledge allowed him to replicate, and in some cases surpass, nature’s work.14 Furthermore, Paracelsus’s interest in the homunculus also reflected his broader quest to uncover the arcana—hidden powers or secrets—of the cosmos. Just as transmutation sought to refine base metals into gold, the creation of a homunculus represented the refinement of raw human essence into a perfected, albeit miniature, being. This approach illustrates how alchemy merged metaphysical beliefs with embryological speculation, creating a hybrid science grounded in mystery, experimentation, and divine aspiration.

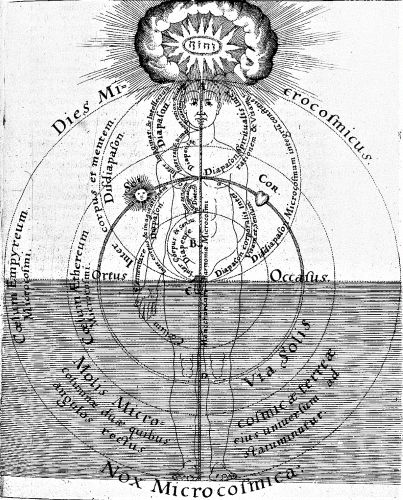

The theological implications of the homunculus procedure are equally significant. Paracelsus did not view the creation of artificial life as an affront to God’s order, but rather as a participation in it. According to his worldview, man was a microcosm (microcosmus) reflecting the macrocosm (macrocosmus) of the universe, and therefore endowed with the potential to reflect divine creativity.15 In this light, the creation of the homunculus was an act of sacred mimicry, echoing the divine act of breathing life into Adam. However, this also carried moral and spiritual risks. Paracelsus cautioned that only the virtuous, pious, and divinely inspired alchemist could undertake such an operation successfully. The creation of life outside God’s will—by an unworthy or impure operator—risked producing monstrosities or spiritual perversions.16 In this sense, the homunculus served as both a symbol of potential and a warning: human ingenuity, if misapplied, could transgress divine boundaries and invoke unforeseen consequences.

Despite its marginal position in Paracelsus’s larger corpus and the skeptical reception it received among later Paracelsians, the homunculus procedure has captured the modern imagination. It influenced literary figures such as Goethe, whose Faust Part II includes a homunculus created by Wagner, as well as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, where artificial life and the consequences of human hubris are central themes.17 In psychoanalytic terms, Carl Jung interpreted the homunculus as a symbolic expression of inner transformation and individuation, linking it to the filius philosophorum—the spiritual child born of the alchemical union of opposites.18 Thus, the homunculus endures not simply as a historical curiosity but as a potent metaphor for creation, transgression, and transformation. Though modern science has moved beyond such speculative physiology, Paracelsus’s vision of the homunculus continues to resonate in cultural narratives that grapple with the ethics of artificial life, technological power, and the limits of human knowledge.

Philosophical and Theological Underpinnings

Paracelsus’ concept of the homunculus was not merely an experimental curiosity, but rather an embodiment of deeply rooted philosophical principles, especially those deriving from Neoplatonism and Christian Hermeticism. The underlying idea that man is a microcosm (microcosmus) reflecting the divine structure of the cosmos (macrocosmus) was central to Paracelsus’s worldview. According to this schema, human beings not only mirrored the universe but also participated in its divine operations through reason and spiritual insight. Creating a homunculus, then, was not an act of prideful hubris, but a theologically inspired extension of humanity’s God-given role as steward and interpreter of nature.19 In this sense, Paracelsus’s homunculus served as a philosophical experiment in imago Dei—a testament to man’s ability to co-create under divine providence, reflecting the Renaissance aspiration to align natural philosophy with sacred purpose.

This theological conviction was undergirded by Paracelsus’s belief in natura naturans—nature as a living, creative force continually shaped by God. In contrast to mechanistic views of nature that would come to dominate Enlightenment thought, Paracelsus viewed the natural world as animated by spiritual intelligences and divine signatures (signatura rerum).20 These “signatures” indicated the inherent virtues and destinies of substances, enabling the alchemist—trained in divine correspondence—to decode and manipulate them toward divine ends. The homunculus, in this paradigm, was not merely an artificial entity, but a vessel for condensed divine essence. It could potentially embody the purest expression of nature’s generative power—if properly conceived through virtuous labor. Thus, the act of generating a homunculus became a sacred imitation of divine creation, requiring not only technical knowledge but moral purity and spiritual alignment with cosmic order.

Paracelsus’s theological anthropology further supports the legitimacy he granted to such creations. He rejected the Aristotelian model that confined generation to the unchangeable laws of biology and instead advocated for a theosophical model in which the human soul and body were products of multiple forces: celestial, elemental, and divine.21 This rejection of classical naturalism opened a conceptual space for human procreation through artificial means—so long as these means aligned with the principles of divine wisdom. In De Natura Rerum, Paracelsus emphasizes that the homunculus is not born from demonic intervention or necromancy, but through arcana naturae—hidden properties within nature, knowable only to the spiritually enlightened.22 Thus, he differentiates his work from magical traditions deemed heretical or occult in the pejorative sense. The homunculus was not a profane intrusion upon nature’s boundaries, but rather the culmination of pious engagement with divine secrets, available only to the philosophus sacer—the sacred philosopher.

Paracelsus’s homunculus also reflects an eschatological hope, deeply informed by Christian soteriology. In this vein, the homunculus can be read allegorically as a representation of the regenerated man—the inner Christ formed through the alchemical purification of the soul. The lapis philosophorum (philosopher’s stone), in Paracelsian thought, often took the form of a perfected inner being, symbolizing the union of opposites and the resolution of dualities.23 Similarly, the homunculus encapsulates the possibility of spiritual rebirth through alchemical practice, mirroring the Pauline ideal of the “new man” in Christ. This esoteric anthropology was closely linked to mystical Christianity, in which the transmutation of base matter was equated with the sanctification of fallen nature. Paracelsus’s creation of the homunculus was thus a dramatization of divine reconciliation and transformation, achievable not through institutional religion alone, but through intimate, experiential gnosis.

The homunculus should be situated within a broader Renaissance attempt to bridge science and theology in pursuit of divine wisdom. Paracelsus belonged to a tradition that saw no contradiction between revelation and experimentation, between piety and empirical inquiry. Indeed, his theological framework demanded that the alchemist be a theologian, a physician of both body and soul.24 In this light, the homunculus serves as both symbol and substance of the alchemist’s calling: to emulate divine creativity while maintaining reverence for cosmic order. As later thinkers like Jacob Boehme and the Rosicrucians interpreted it, the homunculus represented a sacramental understanding of knowledge—where spiritual purity and intellectual endeavor were intertwined. Rather than a monstrous creation, it was an emblem of the harmonization of human nature with divine purpose, realized through disciplined inquiry and mystical devotion.

Historical Context and Reception

The time during which Paracelsus introduced his homunculus concept, the first half of the sixteenth century, was a time marked by religious upheaval, medical revolution, and the expansion of natural philosophy. The Protestant Reformation had already challenged ecclesiastical authority, and with it, traditional cosmologies and understandings of nature. Humanist scholars and radical reformers alike called for the reevaluation of ancient authorities such as Galen and Aristotle.25 In this intellectually fertile environment, Paracelsus positioned himself as a prophetic reformer, not only of medicine but of natural science and theology. His homunculus, described in De Natura Rerum (c. 1537), emerged from this reformist agenda. It rejected scholastic adherence to ancient dogma and emphasized experiential knowledge—what Paracelsus called experientia—as the path to unlocking nature’s hidden truths.26 Alchemy, which Paracelsus considered a divine art, became the instrument through which humanity could imitate and understand divine creation, even to the point of generating life. This radical potential placed his work at the intersection of theological speculation and emerging scientific inquiry.

The reception of the homunculus idea in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was mixed, often filtered through the lens of alchemical literature and the broader Paracelsian movement. Paracelsus’s immediate followers—such as Oswald Croll, Gerard Dorn, and Martin Ruland—embraced the symbolic and metaphysical elements of his teachings, though few took the homunculus procedure literally.27 Many saw it as an allegorical representation of spiritual rebirth or philosophical transformation. At the same time, the notion of artificially creating life intrigued thinkers across Europe, especially as interest in experimental science grew. The homunculus became a point of fascination in early modern debates about generation, spontaneous life, and the limits of human art.28 However, its association with occult practices also drew criticism. By the late seventeenth century, as natural philosophy moved toward mechanistic and empirically grounded methods, figures like Thomas Browne and Robert Boyle dismissed the homunculus as emblematic of outdated magical thinking, albeit with some intellectual sympathy for its symbolic value.29

Despite skepticism among empirical philosophers, the homunculus endured in literature and esoterica, where it was often reinterpreted in light of psychological and spiritual ideas. German Romantic writers, especially Goethe, revived the figure in symbolic and dramatic forms. In Faust Part II, Goethe presents the homunculus as a transparent, brilliant creature generated in a laboratory, embodying the union of intellectual ambition and artificial life.30 This literary reimagining reflects the Enlightenment’s ambiguous relationship with pre-modern science: while rationalism triumphed in the academies, interest in the mystical and irrational persisted in cultural expression. The homunculus thus became a liminal figure, representing both the potential and the danger of scientific transgression. It straddled the line between parody and profundity, science and sorcery, offering a flexible symbol for the evolving anxieties and aspirations of modernity.

In occult traditions and esoteric Christianity, particularly among Rosicrucians and theosophists, the homunculus retained a privileged status as a symbol of the inner spiritual child—the purified self born through the opus alchymicum. Jacob Boehme, for instance, used language reminiscent of Paracelsus in his descriptions of the “new man” forged in the crucible of suffering and divine love.31 In this context, the homunculus was not a literal being but a philosophical metaphor for regeneration and spiritual evolution. This allegorical reading persisted well into the nineteenth century among Hermetic revivalists and even influenced psychoanalytic interpretations in the twentieth century. Carl Jung, in his exploration of alchemical imagery, identified the homunculus with the filius philosophorum, the symbolic child born from the union of opposites in the psyche.32 For Jung, Paracelsus’s homunculus was an early expression of the unconscious projection of individuation—an inward process of becoming whole that reflected outwardly in the myths of artificial life and spiritual rebirth.

Modern historians of science tend to view the homunculus as an illustrative case of the transition from mystical naturalism to mechanistic empiricism. Scholars such as Walter Pagel and Allen Debus have argued that while the homunculus may seem absurd from a modern biological perspective, it exemplifies a serious intellectual engagement with the boundaries of life, art, and nature.33 It also reflects the early modern effort to integrate empirical experimentation with theological significance—a hallmark of Renaissance science. Today, the homunculus is remembered less for its scientific feasibility than for its capacity to encapsulate a cultural moment in which science, magic, and religion were deeply intertwined. Paracelsus’s vision of artificial life anticipated later anxieties about the ethics of creation, echoed in narratives from Frankenstein to contemporary debates over artificial intelligence and synthetic biology. As such, the homunculus remains a potent symbol of human ambition, ingenuity, and the perennial tension between creator and creature.

Symbolism and Legacy

Paracelsus’ homunculus occupies a unique position in the symbolic landscape of Renaissance thought, embodying the complex interplay between human ingenuity, divine imitation, and the hidden operations of nature. On a symbolic level, the homunculus reflects the Paracelsian vision of humanity as microcosmus, a miniature of the greater macrocosmus, capable of shaping and reflecting the cosmic order.34 This microcosmic vision imbued the act of artificial generation with profound metaphysical meaning. The homunculus, rather than a mere laboratory curiosity, functioned as a material allegory for spiritual creation—the forging of a purer self from the raw material of nature. It became a cipher for the process of philosophical and spiritual refinement, comparable to the alchemical lapis philosophorum or the divine child (filius philosophorum) that emerges from the union of opposites in the alchemical wedding. In this symbolic register, the homunculus pointed to humanity’s latent divinity, a spark of creative fire capable of mirroring the generative act of God.

The iconography of the homunculus was deeply resonant with Renaissance and early modern concerns about the boundaries between natural and artificial, divine and human. It captured the fascination and anxiety surrounding man’s ability to manipulate life and matter, straddling the domains of theology, natural philosophy, and proto-science.35 The creation of the homunculus through unnatural but “naturalized” processes—decay, putrefaction, and transformation within the hermetically sealed vessel—evoked both disgust and wonder. Symbolically, it mirrored the alchemical doctrine that true regeneration must arise from death and corruption, echoing Christian themes of resurrection and rebirth. The sealed vessel (vas hermeticum) functioned as both womb and tomb, a microcosmic crucible where the death of the base gives rise to the birth of the perfected.36 In this context, the homunculus transcended literal interpretations, becoming a metaphor for personal transfiguration, intellectual enlightenment, and even divine illumination.

The legacy of the homunculus extended beyond the confines of Paracelsian circles and became a recurring symbol in literature, visual art, and philosophical discourse. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the homunculus was revisited with a blend of satire, reverence, and horror. Goethe’s Faust Part II famously reimagines the homunculus as a luminous, ethereal being born in a laboratory flask—an emblem of pure intellect and disembodied spirit.37 Goethe’s portrayal transformed the homunculus into a figure of aesthetic and philosophical modernity, encapsulating Enlightenment ideals about human rationality, autonomy, and control over nature, while simultaneously critiquing those ideals as spiritually sterile. Similarly, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, though not explicitly invoking the homunculus, echoes its themes in the creation of artificial life and the ethical dilemmas surrounding it. The literary homunculus thus evolved into a symbol of the Promethean impulse—the quest to become a creator—and its attendant dangers of overreach and alienation.

In esoteric and occult traditions, the homunculus continued to function as a spiritual symbol long after mainstream science dismissed it as pseudoscience. Rosicrucian and Hermetic writers treated the homunculus as an allegory for the creation of the “inner man,” the purified soul born from the spiritual and alchemical labor of the adept.38 The mystical child within, born from the union of spirit and matter, became a key trope in theosophical systems that sought to reconcile the material and the divine. In this tradition, the homunculus was less a creature of flesh and more a figuration of inner transformation—a step toward the magnum opus of human spiritual evolution. Even in contemporary New Age and occult discourse, references to the homunculus survive as part of symbolic systems tied to inner alchemy, shadow work, and Jungian individuation. Carl Jung himself identified the homunculus as a projection of the archetypal Self—the totality of the psyche striving for wholeness.39 As such, the homunculus became a permanent fixture in the symbolic vocabulary of spiritual psychology.

Today, the legacy of Paracelsus’ homunculus remains alive in both popular culture and academic discourse. It appears in discussions of artificial intelligence, bioengineering, and synthetic life as a historical antecedent of modern attempts to generate sentient or autonomous beings. The homunculus also provides a lens through which to examine humanity’s enduring fascination with creation, control, and the essence of life.40 In many ways, the homunculus anticipates contemporary debates about the limits of science and the ethical boundaries of innovation. Its symbolic richness allows it to be continually reinterpreted across disciplines—as a metaphor for human creativity, a cautionary tale of hubris, or an emblem of mystical transformation. Far from being a discarded relic of premodern science, the homunculus endures as a vivid reminder of the entanglement of myth, science, and the perennial human desire to transcend the given limits of nature.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Allen G. Debus, The Chemical Philosophy: Paracelsian Science and Medicine in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (New York: Science History Publications, 1977), 1:42–45.

- Lyndy Abraham, A Dictionary of Alchemical Imagery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 2–3.

- Jole Shackelford, A Philosophical Path for Paracelsian Medicine: The Ideas, Intellectual Context, and Influence of Petrus Severinus (1540–1602) (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 2004), 23–26.

- Bruce T. Moran, The Alchemical World of the German Court: Occult Philosophy and Chemical Medicine in the Circle of Moritz of Hessen (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1991), 38–41.

- Paracelsus. De Natura Rerum [Of the Nature of Things]. Translated by Arthur Edward Waite. London: George Redway, 1894.

- Paracelsus, Selected Writings, ed. Jolande Jacobi, trans. Norbert Guterman (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951), 47.

- Walter Pagel, Paracelsus: An Introduction to Philosophical Medicine in the Era of the Renaissance (Basel: Karger, 1958), 113–116.

- William R. Newman, Promethean Ambitions: Alchemy and the Quest to Perfect Nature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 108–112.

- Paracelsus, Of the Nature of Things, 154.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Abraham, A Dictionary of Alchemical Imagery, 28-30.

- William R. Newman, Promethean Ambitions, 132-135.

- Debus, The Chemical Philosophy, 105-108.

- Pagel, Paracelsus, 113.

- Moran, The Alchemical World of the German Court, 41-43.

- Goethe, Faust Part II, trans. Martin Greenberg (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), Act II.

- Carl G. Jung, Psychology and Alchemy, trans. R.F.C. Hull (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968), 162–165.

- Pagel, Paracelsus, 76-78.

- Abraham, A Dictionary of Alchemical Imagery, 177.

- Debus, The Chemical Philosophy, 120-123.

- Paracelsus, Of the Nature of Things, 154.

- Jung, Psychology and Alchemy, 162-165.

- Moran, The Alchemical World of the German Court, 47.

- Pagel, Paracelsus, 52-54.

- Paracelsus, Of the Nature of Things, 153.

- Debus, The Chemical Philosophy, 101-104.

- Newman, Promethean Ambitions, 137.

- Thomas Browne, Pseudodoxia Epidemica, ed. Robin Robbins (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), 106–108.

- Goethe, Faust Part II, Act II.

- Jacob Boehme, The Way to Christ, trans. Peter Erb (New York: Paulist Press, 1978), 93–95.

- Jung, Psychology and Alchemy, 163.

- Allen G. Debus and Walter Pagel, “The Paracelsian Interpretation of Nature,” Ambix 11, no. 3 (1963): 161–172.

- Pagel, Paracelsus, 78-80.

- Newman, Promethean Ambitions, 145.

- Abraham, A Dictionary of Alchemical Imagery, 202-203.

- Goethe, Faust Part II, Act II, Scene 2.

- Frances Yates, The Rosicrucian Enlightenment (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1972), 112.

- Jung, Psychology and Alchemy, 173-175.

- Ariela Freedman and Elizabeth Millán, eds., The Homunculus in Literature and Science, 1500–1900 (Leiden: Brill, 2019), 2–4.

Bibliography

- Abraham, Lyndy. A Dictionary of Alchemical Imagery. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Debus, Allen G. The Chemical Philosophy: Paracelsian Science and Medicine in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. 2 vols. New York: Science History Publications, 1977.

- Debus, Allen G., and Walter Pagel. “The Paracelsian Interpretation of Nature.” Ambix 11, no. 3 (1963): 161–172.

- Freedman, Ariela, and Elizabeth Millán, eds. The Homunculus in Literature and Science, 1500–1900. Leiden: Brill, 2019.

- Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. Faust Part II. Translated by Martin Greenberg. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001.

- Jung, Carl G. Psychology and Alchemy. Translated by R.F.C. Hull. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1968.

- Moran, Bruce T. The Alchemical World of the German Court: Occult Philosophy and Chemical Medicine in the Circle of Moritz of Hessen. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1991.

- Newman, William R. Promethean Ambitions: Alchemy and the Quest to Perfect Nature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

- Pagel, Walter. Paracelsus: An Introduction to Philosophical Medicine in the Era of the Renaissance. Basel: Karger, 1958.

- Paracelsus. De Natura Rerum [Of the Nature of Things]. Translated by Arthur Edward Waite. London: George Redway, 1894.

- Paracelsus. Selected Writings. Edited by Jolande Jacobi. Translated by Norbert Guterman. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951.

- Shackelford, Jole. A Philosophical Path for Paracelsian Medicine: The Ideas, Intellectual Context, and Influence of Petrus Severinus (1540–1602). Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 2004.

- Yates, Frances A. The Rosicrucian Enlightenment. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1972.

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.26.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.