It’s about the gap between our national conversation about health and the structures we actually fund and accept.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

When Rhetoric Meets a Ready-Made Tray

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has built much of his political identity around a populist critique of American health policy — a system he often describes as hijacked by corporate power, nutritional negligence, and government complicity. His rhetoric is rich with warnings about industrial food, pharmaceutical dependence, and the ways in which “Big Everything” has undermined both personal and public well-being. So it came as a surprise — and for many, a disappointment — when Kennedy recently praised Mom’s Meals, a publicly funded service that delivers ready-to-eat meals to seniors, people with chronic illness, and others eligible through Medicare Advantage and Medicaid waivers.

For someone who rails against the ultraprocessed food supply, Kennedy’s endorsement of a company serving shelf-stable Salisbury steak is more than a mixed message. It’s a telling crack in the logic of wellness populism, revealing the tension between rhetoric and the real-world systems candidates must engage with.

What Are Mom’s Meals?

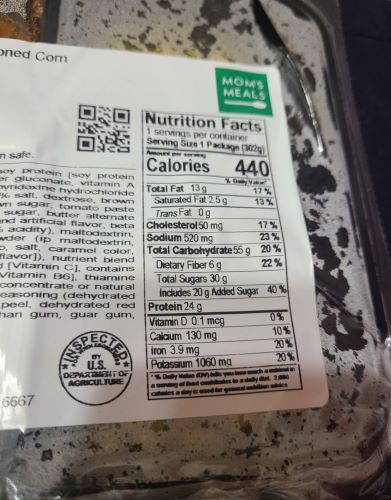

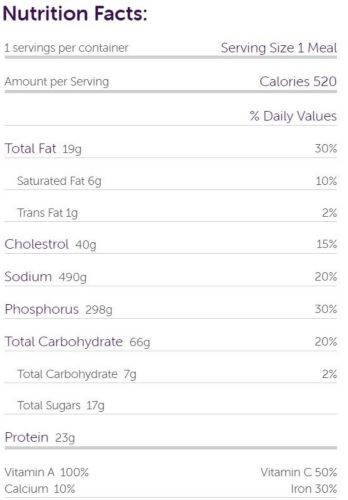

Mom’s Meals, a subsidiary of PurFoods, LLC, operates nationwide as a home-delivered meal service. While technically a private company, its model relies almost entirely on government reimbursement. Meals are “nutritionally tailored” to medical conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, or renal issues — at least according to government guidelines. But the meals themselves often fall short of the nutritional ideals Kennedy has long championed. Ingredient lists routinely include emulsifiers, stabilizers, artificial flavors, and preservatives. Sodium levels are often high, fiber content low, and the meals are designed not for culinary richness but for logistical convenience and low cost.

This puts Mom’s Meals squarely in the domain of ultraprocessed foods — a term that has become central to public health discussions over the last decade. These foods, heavily manipulated and chemically enhanced, have been associated with increased risks of obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and premature mortality. The growing body of research around ultraprocessed diets suggests that the issue isn’t just poor nutritional value, but the biological impact of industrial formulations on the gut, brain, and metabolism.

The Double Bind of Public Nutrition

Kennedy’s praise for the program might stem from compassion — a desire to acknowledge services that feed vulnerable people. But it’s hard to square that kindness with his stated convictions. A campaign grounded in the language of detox, ancestral diets, and decentralization cannot easily justify promoting a model that packages mashed potatoes in vacuum-sealed trays with modified food starch.

The real problem here is structural. Public nutrition programs in the United States are built on compromise: feed as many people as possible for as little money as possible, within the bureaucratic confines of standardized dietary guidelines. These guidelines — which Kennedy has criticized as outdated and corrupt — are the same ones that shape what Mom’s Meals is allowed to offer. In other words, the system isn’t broken because of Mom’s Meals — it’s broken in a way that produces them.

This tension isn’t unique to Kennedy. American food assistance has always been shaped by an uneasy alliance between public welfare and corporate interest. From school lunch programs to SNAP benefits, nutrition policy often dances around the question of real health outcomes in favor of cost efficiency, legal compliance, and industrial scalability.

Processed Compassion Isn’t Reform

Supporters might argue that Kennedy is simply being pragmatic — recognizing a well-meaning program in a deeply flawed system. But for a candidate campaigning on reformist authenticity, that’s a dangerous compromise. The risk isn’t just hypocrisy; it’s dilution. Every time a political figure champions clean food while validating processed models, it weakens the coherence of their message and raises doubts about what “reform” actually means in practice.

Mom’s Meals might deliver calories and meet bureaucratic checklists, but it doesn’t deliver the kind of nourishment Kennedy says he wants for America. It reflects the very conditions — systemic shortcuts, corporate partnerships, and minimal nutritional standards — that he claims are at the root of the country’s chronic disease crisis.

More to the point, for many who look to Kennedy as a voice of alternative health and medical freedom, his support for this program feels like a breach of trust. It’s not just a bad look — it’s a confusing one.

The Political Cost of Processed Optics

There is a broader lesson here, and it isn’t confined to Kennedy. Populist health rhetoric often collides with the realities of public service delivery. Campaigns can promise detoxification and decentralization, but voters still want real-world solutions — meals on the table, support when sick, help for their elders. When the political system offers only a choice between underfunded purity and overprocessed efficiency, most people will choose the tray of food that actually arrives.

But this trade-off shouldn’t be normalized. Candidates like Kennedy have an opportunity — and arguably a responsibility — to push beyond praising the band-aids. If the system only delivers cheap, processed nourishment to people who need real food, then it’s not a success story. It’s a failure of imagination.

Feeding People or Feeding the Machine?

Mom’s Meals is not a villain. In many ways, it’s a symptom. But its sudden spotlight in Kennedy’s campaign highlights a deeper issue: the gap between our national conversation about health and the structures we actually fund and accept.

Kennedy’s mistake may be forgivable, but it is not insignificant. At the heart of his platform is a plea for integrity — for aligning policy with principles. By promoting a program so clearly at odds with those principles, he risks becoming just another voice reshaped by the machinery of compromise.

In the end, the question isn’t whether we should feed people. It’s whether we’re willing to rethink what feeding them actually means.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.11.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.