Kunstmuseum St Gallen/Wikimedia Commons

If the thought of undergoing surgery fills you with dread, spare a thought for your forebears.

By Dr. Adam Taylor / 05.18.2017

Director of the Critical Anatomy Learning Centre

Senior Lecturer in Anatomy

Lancaster University

Surgeries and treatments come and go. A new BMJ guideline, for example, makes “strong recommendations” against the use of arthroscopic surgery for certain knee conditions. But while this key-hole surgery may slowly be scrapped in some cases due to its ineffectiveness, a number of historic “cures” fell out of favour because they were more akin to a method of torture. Here are five of the most extraordinary and unpleasant.

1. Trepanation

Trepanation (drilling or scraping a hole in the skull) is the oldest form of surgery we know of. Humans have been performing it since neolithic times. We don’t know why people did it, but some experts believe it could have been to release demons from the skull. Surprisingly, some people lived for many years after this brutal procedure was performed on them, as revealed by ancient skulls that show evidence of healing.

Although surgeons no longer scrape holes in peoples’ skulls to release troublesome spirits, there are still reports of doctors performing the procedure to relieve pressure on the brain. For example, a GP at a district hospital in Australia used an electric drill he found in a maintenance cupboard to bore a hole in a 13-year-old boy’s skull. Without the surgery, the boy would have died from a blood clot on the brain.

2. Lobotomy

It’s hard to believe that a procedure more brutal than trepanation was widely performed in the 20th century. Lobotomy involved severing connections in the brain’s prefrontal lobe with an implement resembling an icepick (a leucotome).

Antonio Egas Moniz, a Portuguese neurologist, invented the procedure in 1935. A year later, Walter Freeman brought the procedure to the US. Freeman was an evangelist for this new form of “psychosurgery”. He drove around the country in his “loboto-mobile” performing the procedure on thousands of hapless patients.

Instead of a leucotome, Freeman used an actual icepick, which he would hammer through the corner of an eye socket using a mallet. He would then jiggle the icepick around in a most unscientific manner. Patients weren’t anaesthetised – rather they were in an induced seizure.

Thankfully, advances in psychiatric drugs saw the procedure fall from favour in the 1960s. Freeman performed his last two icepick lobotomies in 1967. One of the patients died from a brain haemorrhage three days later.

Walter Freeman (left) and James Watts study an x-ray prior to conducting ‘psychosurgery’. Wikimedia Commons/Harris A Ewing

3. Lithotomy

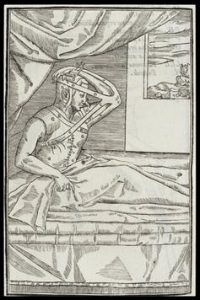

This Dutch blacksmith, Jan de Doot, removed his own bladder stone. Wikimedia Commons

Ancient Greek, Roman, Persian and Hindu texts refer to a procedure, known as lithotomy, for removing bladder stones. The patient would lay on their back, feet apart, while a blade was passed into the bladder through the perineum – the soft bit of flesh between the sex organ and anus. Further indignity was inflicted by surgeons inserting their fingers or surgical instruments into the rectum or urethra to assist in the removal of the stone. It was an intensely painful procedure with a mortality rate of about 50%.

The number of lithotomy operations performed began to fall in the 19th century, and it was replaced by more humane methods of stone extraction. Healthier diets in the 20th century helped make bladder stones a rarity, too.

4. Rhinoplasty (old school)

Syphilis arrived in Italy in the 16th century, possibly carried by sailors returning from the newly exploited Americas (the so-called Columbian exchange).

The sexually transmitted disease had a number of cruel symptoms, one of which was known as “saddle-nose”, where the bridge of the nose collapses. This nasal deformity was an indicator of indiscretions, and many used surgery to try and hide it.

A patient undergoing Tagliacozzi’s procedure for fixing saddle-nose. Wikimedia Commons/Wellcome Images

An Italian surgeon, Gaspare Tagliacozzi, developed a method for concealing this nasal deformity. He created a new nose using tissue from the patient’s arm. He would then cover this with a flap of skin from the upper arm, which was rather awkwardly still attached to the limb. Once the skin graft was firmly attached – after about three weeks – Tagliacozzie would separate the skin from the arm.

The were reported cases of patients’ noses turning purple in cold winter months and falling off.

Today, syphilis is easily treated with a course of antibiotics.

5. Bloodletting

Losing blood, in modern medicine, is generally considered to be a bad thing. But, for about 2,000 years, bloodletting was one of the most common procedures performed by surgeons.

The procedure was based on a flawed scientific theory that humans possessed four “humours” (fluids): blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile. An imbalance in these humours was thought to result in disease. Lancets, blades or fleams (some spring loaded for added oomph) were used to open superficial veins, and in some cases arteries, to release blood over several days in an attempt to restore balance to these vital fluids.

Bloodletting in the West continued up until the 19th century. In 1838, Henry Clutterbuck, a lecturer at the Royal College of Physicians, claimed that “blood-letting is a remedy which, when judiciously employed, it is hardly possible to estimate too highly”.

A barber surgeon’s bloodletting set. Anagoria/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Finally, one medical procedure, dating from one of the earliest Egyptian medical texts, that isn’t used anymore – and I can’t for the life of me think why – is the administration of half an onion and the froth of beer. It cures death, apparently.

Originally published by The Conversation under a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.