Registered Black voters had been removed from the rolls.

By Dr. Jerald Podair

Professor of History

Lawrence University

Introduction

Mose Norman, a Black registered voter, was ready to cast his ballot for presidential candidate Warren G. Harding.

But when he arrived at his polling place on Election Day, Nov. 2, 1920, in the orange grove town of Ocoee, Florida, near Orlando, Norman was turned away by white election officials because of supposed unpaid poll taxes. His name and the names of hundreds of other registered Black voters had been removed from the rolls by white poll workers.

The Black voters were told that only the notary public could verify their registrations, and he was out of town. When Norman and the other Black voters protested, the poll workers physically kicked them out of the building.

The racial tension only got worse as the day went on. In Ocoee, Election Day ended in a lynching.

In what became known as the largest incident of Election Day violence in U.S. history, the tragedy in Ocoee stands as a stark reminder of the racist barriers Black voters faced as they attempted to exercise their basic right to vote.

But while passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 outlawed the use of racist literacy tests and poll taxes to bar Black voters, that legislation was too late to help Ocoee’s Black residents. The majority of Black people in Ocoee in 1920 lost their homes, and as many as 60 of them lost their lives.

‘The Night the Devil Got Loose’

The violence in Ocoee was not surprising, given the white-supremacist Ku Klux Klan’s efforts to intimidate Black voters and their Republican allies before the election.

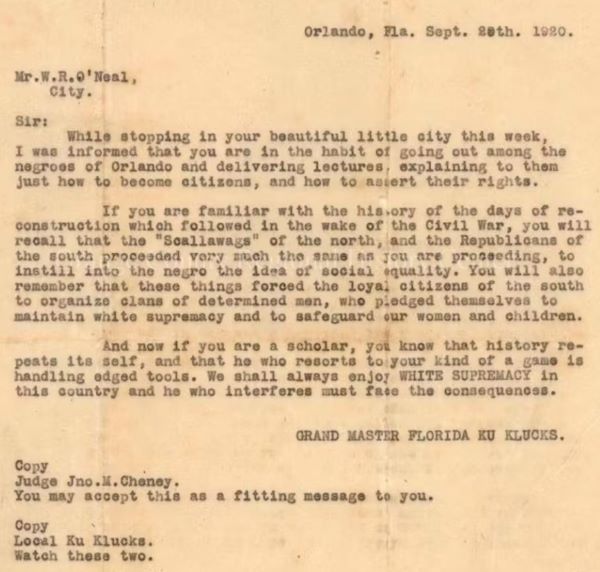

In addition to marches throughout the state, the Ku Klux Klan grand master in Florida sent a letter to Republican politician William R. O’Neal, who was openly courting Black voters in his bid to become a U.S. senator.

The letter threatened O’Neal if he continued “going out among the negroes of Orlando … explaining to them just how to become citizens, and how to assert their rights.”

The letter concluded: “We shall always enjoy WHITE SUPREMACY in this country and he who interferes must face the consequences.”

The local branch of the Ku Klux Klan in Ocoee also told a former judge that if any Black residents attempted to vote “… there would be serious trouble.”

For Norman, that trouble occurred after he tried again to vote at a different precinct in Ocoee. After being denied again, Norman was then assaulted by a local police officer. Somehow, Norman managed to escape and fled to the home of his friend July Perry, a successful Black businessman, community leader and voting rights advocate.

Perry was well known for paying the poll taxes of local Black voters who could not afford them.

But once Norman arrived at Perry’s house, a mob of white Ocoee residents and Ku Klux Klansmen tried to arrest both him and Perry. A gunfight ensued, leaving several white men injured and two dead. The remaining mob decided to burn down Perry’s home.

Norman escaped again, but police officers arrested Perry, his wife and their 19-year-old daughter. While the two women were driven to jail in a nearby city, Perry was taken to the Orange County jail. He was not there long.

The white mob rushed the jail, took Perry out, beat him and finally lynched him.

The mob then descended on Ocoee’s Black community, destroying most of the homes, churches and businesses.

“That’s the night the devil got loose in Ocoee,” recalled a survivor decades later.

Shortly after the election, more than 200 Black residents fled the city, never to return. Of the 255 Black residents listed in the 1920 U.S. census report, only two Black people remained.

The Federal Response

Shortly after Election Day, the NAACP, the nation’s leading civil rights organization, conducted an investigation into what happened in Ocoee.

Their findings were submitted to the U.S. House of Representatives Census Committee in December 1920 as part of a hearing on the violence in Ocoee and other efforts to suppress the Black vote.

“At the time that I visited Ocoee,” NAACP investigator Walter White wrote in December 1920:

“The last colored family of Ocoee was leaving with their goods piled high on a motor truck with six colored children on top. White children stood around and jeered the Negroes who were leaving, threatening them with burning if they did not hurry up and get away.”

But in its own investigation of Ocoee, the U.S. Department of Justice found “no attempt to intimidate any Negroes in the casting of their ballots, and that there was no interference with the voting of qualified Negroes.”

In addition, a Florida grand jury found “no evidence against any one or group of individuals as to who perpetrated the fatalities” that occurred on Nov. 2, 1920.

July Perry was no radical. He was a deacon in the church, a labor leader and a member of the local fraternal lodge. For him, the right to vote was central to what it meant to be as American as his white neighbors.

For that, Perry was lynched and his body hung from a light pole.

For July Perry’s heirs, the violent history of voting cannot be overlooked as legal challenges to the Voting Rights Act wind their way through the courts and voter identification requirements grow stricter.

For Black voters, the past is never past.

Originally published by The Conversation, 11.01.2024, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.