Exploring ancient Roman markets and meals.

By Dr. Douglas Kenning

Instructor of History

Osher Lifelong Learning Programs

The Fromm Institute for Lifelong Learning

Meals

Ientaculum

Breakfast was served around dawn, and tended to be a light meal, primarily of bread, sometimes dipped in wine or olive oil or honey, perhaps accompanied by cheese and olives. Midday lunch was small.

Cena

This was the main meal of the day.

Cena in the period of the Etruscan kings and early Republic was taken around 11:00 and was based around a basic starch in the form of a porridge, the puls, made from emmer, water, salt, and fat (olive oil if you could afford it), with an accompaniment of whatever vegetables were available. The richer classes ate their puls with eggs, cheese, and honey and (less often) with meat or fish.

Over the course of the Republic Period, the cena developed into two courses: a main course and a dessert with fruit and seafood (e.g. mollusks, shrimp). Then, as the Roman world expanded and Greek influences predominated, cena for the upper classes moved to the afternoon and grew into a large meal in three parts: first course (gustatio), main course (primae mensae), and dessert (secundae mensae). As a result, the vesperna appeared, a light evening meal or snack. This is the pattern in modern Italian society. In the lower classes, however, the evening cena was never abandoned because it corresponded more closely to the daily rhythms of manual labor

Into the Imperial Period, the cena moved back into the evening and a midday lunch reappeared, called the prandium. The prandium often was a kind of snack, consisting perhaps of leftovers from the night before or cold meat and bread.

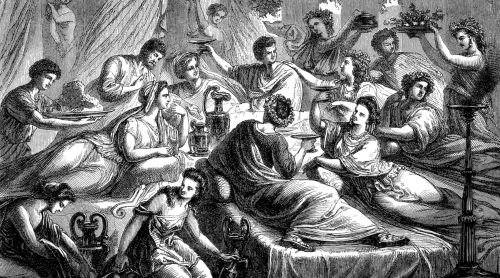

Among the members of the upper classes, it became customary to schedule all business obligations in the morning. After the prandium, the last of the day’s business would be concluded and men would gather at the public baths. In late afternoon, the cena would begin, which could last until late in the night, especially if guests were invited, and would often be followed by a comissatio (a round of drinks).1

Categories of Foods and Eating

Appetizers and Side Dishes

These often arrived at the cena table in multiple courses.

Cold clams and oysters (typically farmed), originally dessert dishes, later became starters. Stewed and salted snails, raw or cooked clams, sea urchins and small fish often began meals.

Among pulses, only lentils imported from Egypt were liked by the upper class. Everyone ate mushrooms, such as boletus, field mushroom and truffle.

The Romans pickled many things in vinegar, including escarole, zucchini, olives, chicory, chard, cardoons, mallows, broccoli, asparagus, artichokes, leeks, carrots, turnips, parsnips, beets, peas, green beans, radishes, cauliflower, cabbage, lettuces and field greens, onions, cucumbers, fennel, melons, capers and cress. Both the green and the white parts of chard were used.

Under the Empire, a taste for dormice developed, which were bred in special enclosures before being fattened-up in clay pots called gliraria. Small birds like thrushes fed both upper and lower classes.

Bread and Dairy

Barley and varieties of wheat has been used in baking at least since ca. 9,000 BCE (in Anatolia).

Up to the Roman Empire Period, bread could be made (flat, round loaves) only from emmer, (a cereal grain closely related to wheat). The upper classes consumed this, along with, eggs, cheese, honey, and milk. Beginning around the Christian era, bread began to be made of wheat. The bread was sometimes dipped in wine and eaten with olives, cheese, crackers, and grapes. By 100 CE there was rye and cultivated oats. Durham wheat necessary for pasta came to Italy through the Arabs seven hundred years later

Cheese was plentiful, popular, and sometimes the chief food of the poor.

Butter, that original gift of the Mongols, was almost unknown, Pliny calling it a food of the barbarians and Strabo that the people of the Pyrenees “their butter serves them as oil”. Instead, for the Greeks and Romans both, full-fat cream cheese or lard was used for baking and other purposes.

Fruit

Grapes for eating were a favorite, being sweet and plentiful, as were raisins. Also, pomegranates, quinces, apples, apricots, peaches, cherries, pears, plums, currants, strawberries, blackberries, medlars, elderberries, mulberries, citron, raspberries, and melons were grown. crab apples grew abundantly, as Cato observed, and the Romans took rapidly and happily to fruit culture, learning from the Etruscans. They took a very scientific approach to grafting and selecting for qualities; Pliny claims to have seen one tree with different branches bearing apples, cherries, grapes, pears, walnuts, and pomegranates (which is impossible, but suggestive of their skill). By the middle of the first century BCE, Varro could claim that all the Italian peninsula was one vast orchard The Romans also promoted an expanding luxury export trade in fruits, especially to north of the Alps.

In Greek and Roman theatres, vendors walked about selling dates, wrapped in gilded paper.

Figs were enjoyed plain for dessert or soaked in warm water and wine, then cooked separately and served as an accompaniment to pork.

Vegetables

The leaves of many shrubs and weeds were cooked to a mush and strongly spiced; examples are elder, mallow, orache, fenugreek, nettles, and sorrel.

By the Empire, decadent Romans considered common vegetables as food for peasants, and ceased to eat them (though exotic vegetables like asparagus were prized). The main exception was lettuce; its reputation as a sedative, made it a popular choice to finish a meal.

Spinach and eggplant did not arrive until the 9th century (through the Arabs). Tomatoes and potatoes, of course, came in modern times from the Spanish New World.

Meat and Fish

The upper classes ate as much meat as possible; Emperor Maximus ate forty pounds of meat a day. Like Henry VIII and for the same reason, he was huge.

Beef was not eaten widely, as cattle were needed to work, rather than being bred solely for their meat. Thus, those that were consumed mostly were old, their meat tough and needing long cooking. Better quality beef, though, often was available after religious sacrifices, and butcher shops tended to set themselves up near temples.

Pork was the most popular meat. All parts of the pig were eaten, and more unusual parts like the breasts and uteruses of young sows were considered specialties. Pig’s ears were also a delicacy. For special effects, whole pigs were stuffed with sausages and fruit, roasted and then served on their feet. When cut, the sausages would spill from the animal like entrails. Such a pig was called a porcus Troianus (“Trojan pig”), a humorous reference to the Trojan Horse.

Sausages, farcimen, were made of beef and pork according to an astonishing diversity of recipes and types. Particularly widespread was the botulus, a blood sausage somewhat like black pudding, and which was sold on the streets. The most popular type of sausage was the lucanica, a short, fat, rustic pork sausage, the recipe for which is still used today.

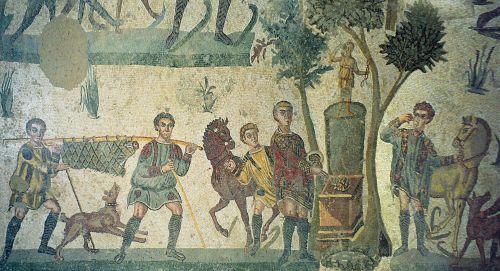

Game, of all sorts, the more exotic the better, stews of all manner of mixtures of meats, and decadent frivolities such as cow vulvas and teats, calves testicles.

Fish was a stable in the Republic, but less so under the Empire. Despite the vast resources of the Mediterranean, fish remained expensive. As with all foods, the Romans liked to try to farm it, but fish farming, in freshwater and saltwater ponds, was not hugely successful. During the Republic, the goatfish, mullus, was a luxury food, above all because its scales exhibit a bright red color when it dies out of water. For this reason these fish were occasionally allowed to die slowly at the table. At the beginning of the Empire era, however, this custom ceased among the aristocracy and became a sign of a parvenu.

Geese were bred for eating and sometimes fattened. Foie Gras the Romans learned from the Greeks and it became a great favorite; Pliny, Cato, Juvenal all wrote at length about stuffing geese (with dried figs mostly) and serving of goose liver (Juvenal suggested soaking it in milk and honey). So popular was the fig-feeding method (which made the birds highly diabetic) that “fig liver,” iecur ficatum, became the standard phrase for all foie gras. The Gauls learned the method, borrowing the word, ficatum, which became figido in the 8th Century, fedie in the 12th, then feie, finally foie. This is how the roman word for “fig” became the modern French word for “liver”

Chicken was rarer and more expensive than duck. Other birds like peacocks and swans were eaten on special occasions. Capons and poulards (spayed hens) were considered specialties. In 161 BCE the consul C. Fannius prohibited the consumption of poulards, though the ban was ignored.

Rabbits were bred widely. Newborn rabbits or rabbit fetuses, known as laurices, were considered a delicacy. Hares could not be domesticated, so were four times more expensive than rabbits. The shoulder of the hare was especially favored.

Spices

Garum was the universal sauce added to many dishes (like soy in East Asian dishes). It was prepared by subjecting salted fish remains (after cleaning), in particular mackerel intestines, to two to three months of heating, usually by exposure to the sun, as the protein-laden fish parts decomposed. The resulting mass was then filtered and the liquid traded as garum. Because of the stink, production of garum within the city was banned. Garum, supplied in small sealed amphorae, was used throughout the Empire and mostly replaced salt as a condiment. Compare the various dark fermented fish sauces of Southeast Asia (e.g. nam pla).

Spices, especially pepper but hundreds of other kinds too, were imported on a large scale and used copiously. Silphium was a popular plant-based spice that became extinct through over cropping. The inherent flavors of vegetables and meat were completely masked by the heavy use of garum and other seasonings. It is only a slight exaggeration that, in the finest dishes, a gourmet was pleased if he could tell neither by sight, nor smell, nor taste what the ingredients of a dish were.

Salt gave way to garum in most Roman dishes, but was absolutely necessary as a preservative.

Cinnamon as spice was not known until 3d or 4th Century CE, previously used as medicine (diarrhea), cordial, and aphrodisiac.

Drink

Wine fermentation was not controlled, making for a high alcohol content, so in the Greek way they mixed water into the wine immediately before drinking. Wine was sometimes adjusted and “improved” by its makers: instructions survive for making white wine from red and vice versa, as well as for rescuing wine that is turning to vinegar. Wine was also variously flavored. For example, there was passum, a strong and sweet raisin wine, for which the earliest known recipe is of Carthaginian origin; mulsum, a freshly made mixture of wine and honey; and conditum, a mixture of wine, honey and spices made in advance and matured. One specific recipe, conditum paradoxum, is for a mixture of wine, honey, pepper, laurel, dates, mastic, and saffron, cooked and stored for later use. Another recipe called for the addition of seawater, pitch and rosin to the wine. A Greek traveler reported that the beverage was an acquired taste. Sour wine mixed with water and herbs (posca) was a popular drink for the lower classes and a staple part of the Roman soldier’s ration.

Beer (cervesa), the drink of choice for thousands of years in Mesopotamia and Egypt, was considered vulgar by cultured Romans.

Desserts and Sweets

Lacking cane sugar, honey desserts were a standard of Roman feasts, honey to coat fruits, flowers, seeds, stems, to preserve them or for confectionery (as still defines many Mediterranean sweets). Cane sugar arrived first as a rumor. Alexander’s admiral, Nearchus, heard of a honey extracted by boiling a cane. Centuries went by. Then the major Roman writers began to comment on it. “There is a kind of solid honey called saccharon (from the Sanskrit, sarkara), which is found in the reeds of India and Arabia the fortunate. It resembles salt in consistency, and crunches in the mouth” wrote Dioscordies, Greek contemporary of Caesar Augustus. Pliny tells that that at this time it was used only to help medicine go down. Half a millennium would pass before the Arabs taught Europe to replace honey with sugar

In addition to honey, foods were sweetened with date syrup and other fruit syrups.

Walnuts, hazelnuts, almonds, chestnuts and pine nuts were popular dessert snacks. Roman bakers were famous for the many varieties of breads, rolls, fruit tarts, sweet buns and cakes, made of wheat and usually soaked in honey

The Poor and Markets

The lower classes consisted of peasants, artisans and smiths, legionaries (soldiers) and gladiators, and lowest of all, slaves. Both the rural poor, who would have had small subsistence farms, and the urban poor of Rome normally could not afford much more than salt fish, vegetables, fava beans, chickpeas, green peas and lupins (foods the moneyed classes disdained). Only on festival days or military triumphal parades would more meat be distributed to commoners. Never butcher beef, however, which was the height of luxury.

“The shops, rather stalls, on the ground floor of the . . . brick . . . Roman market halls opened straight on to the street. They sold the seasonable vegetables, fruit and flowers . . . as well as early produce. Displays spilled from shallow loggias and out into the street, itself crowded with shoppers, idlers, pickpockets, and people pushing handcarts.

On the first floor, where a gallery of arcades let the daylight into a succession of vaulted rooms, jars carefully labeled and ranged in order held wines and oils from all over the world. There were also smaller rooms where the wholesalers’ bookkeepers did their work.

Flights of stairs led up to the second and third floors, which were fragrant with spices, both familiar and rare, worth a fortune and requiring armed guards to protect them day and night. . . . .

The fourth floor was busy with the administrative staff of scribes working on the files . . . This part of the building accommodated offices of the annona, the social security organization which distributed grain to the poor, either free or at subsidized prices. The tax inspectors and security services also had their headquarters here. . . . Inspectors of weights and measures, brokers, traders and banking agents also went about their business on the fourth floor.”2

Endnotes

- Information taken from Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat, A History of Food, trans. Anthea Bell; Wikipedia: Ancient Roman Food; and Sarah Weise, Miami University, https://www.vroma.org/~plautus/foodweise.html.

- Quotations are from Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat, A History of Food, trans. Anthea Bell.

Originally published by the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute, Sonoma State University, to the public domain.