Black newspaper editors saw these emblems clearly for what they stood for – a lost cause.

By Dr. Donovan Schaefer

Associate Professor of Religious Studies

University of Pennsylvania

Introduction

In October 2023, nearly seven years after the deadly Unite the Right white supremacist rally, the statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee in Charlottesville, Virginia, was melted down. Since then, two more major Confederate monuments have been removed: the Confederate Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery and the Monument to the Women of the Confederacy in Jacksonville, Florida.

Defenders of Confederate monuments have argued that the statues should be left standing to educate future generations. One such defender is former President Donald Trump, the likely GOP presidential nominee in 2024.

“Sad to see the history and culture of our great country being ripped apart with the removal of our beautiful statues and monuments,” Trump tweeted in 2017. “The beauty that is being taken out of our cities, towns and parks will be greatly missed and never able to be comparably replaced!”

But since the end of the Civil War, journalists at Black newspapers have told a different story. Despite meager financing and constant threats, these newspapers represented the views of Black Americans and documented the nation’s shortcomings in achieving racial equality.

According to many of these writers, the statues were never designed to tell the truth about the Civil War. Instead, the monuments were built to enshrine the the myth of the “Lost Cause,” the false claim that white Southerners nobly fought for states’ rights – and not to preserve slavery.

In 1921, for instance, the Chicago Defender published an article under the headline “Tear the Spirit of the Confederacy from the South” and called for the removal of the statues from across the country because they “lend inspiration to the heart of the lyncher.”

‘Lost Cause’ Propaganda

For the last several years, I’ve studied the history of Confederate monuments by poring over the letters and records of the organizations that campaigned for their construction. My research students and I have also reviewed countless reactions to the monuments published in real time in Black newspapers.

What is clear is that from the late nineteenth century until today, Confederate monuments were part of a relentless propaganda campaign to restore the South’s reputation at dedication ceremonies, parades, reunions and Memorial Day events.

The dedication in Charlottesville of the Lee monument in 1924 – 100 years ago this May – was one such event.

Timed to coincide with a reunion of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, the speakers openly bragged about how they were sweeping Northern-authored textbooks out of Southern schools and replacing them with friendlier accounts of the Civil War.

In the weeks leading up to the dedication, members of the Ku Klux Klan paraded down Charlottesville’s Main Street in daylight and burned crosses in the hills at night.

The master of ceremonies of that unveiling was R.T.W. Duke, Jr., the son of a Confederate colonel who was a popular orator at events like these.

A few years earlier, Duke made his own views of the Civil War plain.

He told a crowd gathered at a Confederate cemetery in Richmond, Virginia, that he was “still a believer in the righteousness of what some of our own people now call the ‘rebellion.‘”

Duke further said “that slavery was right and emancipation a violation of the Constitution, a wrong and a robbery.”

A Critical Black Press

Contrary to the claims of today’s defenders of Confederate monuments, a review of Black newspapers going back to the 1870s conducted by my research team shows that Black journalists’ criticism of these memorials had already begun by the late nineteenth century.

The first truly national Confederate monument was the statue of Robert E. Lee in Richmond. It was unveiled before an audience of as many as 150,000 attendees on May 29, 1890, and provoked sharp alarm among Black commentators across the country.

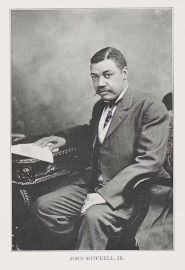

In a May 31, 1890, article, Richmond Planet editor John Mitchell, Jr. pointed out that Confederate flags and emblems far outnumbered U.S. flags at the unveiling.

“This glorification of States Rights Doctrine, the right of ‘secession’ and the honoring of men who represented that cause, fosters in this Republic the spirit of Rebellion and will ultimately result in handing down to generations unborn a legacy of treason and blood,” Mitchell wrote.

Mitchell further detailed the enthusiasm of the crowd assembled in Richmond.

“Cheer after cheer rang out upon the air as fair women waved handkerchiefs and screamed to do honor,” Mitchell wrote. But the South’s insistence on celebrating Lee “serves to retard its progress in the country and forges heavier chains with which to be bound.”

By reprinting articles from other Black publications, the Planet in 1890 effectively created a forum for commentary on the Richmond Lee statue from around the country.

An article republished from the National Home Protector, a Baltimore-based Black newspaper, also took aim at the statue.

“When the unveiling of the monument is used as an opportunity to justify the southern people in rebelling against the U.S. government and to flaunt the Confederate flag in the faces of the loyal people of the nation the occasion calls for serious reflection,” the article said.

The editors of the newspaper accused white Southerners of trying to use the glorification of Lee to resurrect the “corpse of rebellion.”

Writing Truth to Power

No one knows what the Black-owned Charlottesville Messenger said about the unveiling of the Lee monument in its city in 1924.

Only one copy of a single issue still exists. In fact, one of the only things known about the Messenger is that in 1921, the white-dominated Charlottesville Daily Progress reprinted a Messenger article that called for Black civil rights. The Black newspaper later retracted the story after receiving threats from white supremacists.

But we do know what other Black newspapers of this period were saying about Confederate monuments. For many Black editors, the monuments had become symbols of the violent backlash against Black citizenship by white Southerners.

In 1925, the Pittsburgh Courier, criticized the Confederate carving on Stone Mountain in Georgia, the site of the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan.

Taking square aim at the Lost Cause myth, the newspaper called Stone Mountain “a living monument of the cause to which white Southerners have dedicated their lives: human slavery and color selfishness.”

The Confederate monument on the side of Stone Mountain still stands today.

Telling the truth about American history requires transforming these memorials into true reflections of the seemingly never-ending battles initially fought during the the Civil War.

Originally published by The Conversation, 01.30.2024, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.