Friendship had an integral place in the formation of social bonds and political groupings.

By Dr. Julian P. Haseldine

Professor of History Emeritus

University of Hull

Abstract

This article proposes a model of political friendship in the European Middle Ages drawn from current research into medieval friendship networks. It reviews the main interpretive and methodological developments in network studies for this period, now emerging as a distinct research area from the more established fields of the theory and philosophy of friendship and the study of particular relationships and their emotional content. Recent research proposes friendship as a distinct category of social and political relations separate from patronage, kinship and other bonds, in ways which mark a break from earlier, anthropologically-based approaches. Medieval friendship was a formal, public bond to which collective and institutional relationships were integral and which was emotional but not private or individualistic. Trust-building is proposed as an interpretive framework which can account for the historical evidence of friendships in practice in ways which established models of spiritual, affective or instrumental friendship cannot. Finally, it is suggested that the apparent discontinuities with modern friendship relate more to differences in discourse and ethical framing than to the practical experience of friendly bonds, and that functional rather than theoretical studies of medieval friendship offer a basis for comparative study of modern and pre-modern friendship.

Introduction

The relationship between friendship and politics in medieval Europe can appear to be fundamentally different from that experienced in modern societies. Friendship has, for some time, been recognised by medievalists as having an integral place in the formation of social bonds and political groupings and as contributing to the creation and maintenance of political order (see Althoff 1990; Le Jan 1995; Mullett 1997; Haseldine ed. 1999). While this has parallels with emerging research into political friendship in modern societies, the ideology of friendship in the Middle Ages and its perceived ethical relation to politics were very different. We are also only just beginning to understand the nature of the structures created by friendship bonds and their practical impacts on political activity in the Middle Ages.

This essay proposes a model for political friendship as it functioned in the European Middle Ages, as this is emerging from current research into friendship networks, which, it is hoped, might stand as a basis for comparison with friendship structures and modes observed in other periods and regions, contributing thereby to the longer history of the experience of friendship and politics currently being developed through an increasing number of inter-disciplinary and multi-period projects and publications (see Classen and Sandidge eds. 2010; Descharmes et al. eds. 2011). This is distinct from the study of the theoretical and literary tradition of medieval friendship and from that of particular relationships and their emotional content, related but separate areas which have generated extensive literatures. This paper will assess some of the methods developed by medievalists to analyse friendship structures and will also suggest that the apparent radical discontinuities between pre-modern and modern experiences may relate more to changes in the articulation of idealised friendship and its ethical framing than to fundamentally different experiences of friendly bonds in practice.

True and False Friendships and Medieval Ideas of Friendship

The relationship between friendship and politics in medieval Europe was articulated explicitly as a positive one. Friendship, at least in its idealised ‘true’ form (amicitia uera, ‘true friendship’, in Latin), was regarded as integral to politics and as inherently ethically good. The medieval concept of friendship was derived from the classical tradition where true friendship was defined principally in relation to virtue and was seen as a strong personal bond but one which united the virtuous to the greater good and so as integrally related to political interactions and to what is often conceived of as the ‘public sphere’ in modern idiom (see Konstan 1997; McEvoy 1999; Burton 2011). Nor was there in principle any necessary tension between friendly bonds and patronage in ways which, in modern societies, have come to be problematised as nepotism or favouritism; indeed, supporting kin and friends was generally regarded as a duty. In the Middle Ages, an ideology of friendship developed which regarded the bond as an extension of the activity of God in the world, a theory again derived from ancient philosophies which saw it as a natural or physical force for universal harmony (see White 1992, pp. 17-19; Cassidy 1999, pp. 51- 59). Friendship was thus held to arise externally to the human mind and to represent the intersection of a universal moral order with humanity.

This standpoint underlies the common medieval formulations that one’s friends were simultaneously the friends of truth or the friends of God, often invoked in political conflicts where they functioned as markers of inclusion for élite political groupings and to invest partisan interests with universal moral claims (see Robinson 1978; Saurette 2010b; Haseldine 2010). Articulations of friendship in medieval sources also frequently make reference to the ancient tradition by allusion to or quotation from classical works, a phenomenon which has been extensively studied and which is part of the broader history of the reception of classical literature in the medieval West. This remains one of the most prolific areas of research into medieval friendship (see White 1992; McEvoy 1999; Cassidy 1999; Jaeger 1999, pp. 27-35; Sère 2007; Mews 2007; Nederman 2007). This allowed friendship to enter the political discourse readily, but at the same time, as we shall see, the invocation of this idealised friendship by contemporary actors can obscure more than it illuminates the formation and operation of actual friendship networks and the social contexts in which they arose.

There are very many different aspects of this theoretical tradition, but one in particular merits further note in the context of network analysis. It differentiated between truth and falsity in friendship on the basis not of emotional compatibility or feelings but of the effects of the friendship. False friendships were those which served only the mutual gain or pleasure of the participants and which worked against the common good. True friendships, those which furthered positive moral ends in society, were held to be unchanging and, as divinely inspired bonds among the virtuous, could exist independently of, or predate, personal acquaintance (see Haseldine 1994; Goetz 1999). Thus, for example, in the Middle Ages professions of friendship to virtuous strangers in letters were not uncommon and friendships between individuals and institutions were routine; at the same time betrayals of common interests were held to show that a supposedly true friendship had been false all along (Haseldine ed. 1999, pp.xvii-xviii; cf. Saurette 2010a, p.293). Emotional compatibility was something which true and false friendship could share equally and was not diagnostic of a ‘genuine’ relationship. This means that the sources tend to conceal the different origins of friendship relationships, articulating them all in similar ideal terms and thus making it difficult to detect different degrees of affection or acquaintance behind formally professed friendships. While, therefore, there was an acknowledgement of profound tensions between ideal and real friendships, these were very different from those which concern modern theorists, such as favouritism or nepotism.

Recently, students of modern society have sought to understand friendships in politics either in a more positive ethical light or from an analytically neutral position, developing models of embeddedness, trust and social capital to accord friendship an integral and structuring, rather than a marginal and corrupting, role in professional, social and political relationships, and questioning modern assumptions about the essentially ‘private’ nature of friendship or the existence of a ‘pure’ or ‘genuine’ sphere of personal bonds separately from other social or political contexts (see Lyon, Möllering and Saunders eds. 2012; Castigilione, Van Deth and Wolleb eds. 2008). Friendship is increasingly seen as an important part of our understanding of the political in many modern contexts (for a recent critique and references, see Devere 2011). Medievalists have had, in some ways, to approach the question from the opposite direction, using sources which articulate friendship as an inherently political phenomenon, transcending, sublimating or existing outside personal relationships.

Interpretations of Medieval Friendship

In his studies of the letters of St Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109), R. W. Southern noted the use of very similar, and highly affective, language directed apparently without distinction to recipients with very different degrees of personal acquaintance to the writer, from intimates to strangers. He postulated a well-known model of spiritual friendship as the sublimation of particular human bonds in the contemplative quest for God, in which friendship became an idea rather than an emotional bond and so a spiritual experience which could be shared beyond the sphere of strong personal ties (Southern 1963, pp.67-76; 1990, pp.138-165). One implication of Southern’s conclusions was that in any particular relationship personal affections could not be inferred from affectionate language without circularity of argument, as the language itself was evidently not restricted to one type of personal relationship. This called attention to what was to become one of the central issues in subsequent studies of medieval friendship networks – that there is no direct link between the nature of relationships and the vocabulary used to describe them.

In one of the most influential works on medieval friendship, Brian Patrick McGuire interpreted monastic friendship literature as evidence for the development over time of interest in human emotions, an argument which was also related in part to important debates over the medieval origins of Western individualism (McGuire 1988). Unlike Southern, McGuire did seek to identify personal emotional bonds and feelings on the basis of the language used; he also identified such relationships as genuine, in contrast to the instrumental relationships, lacking emotional content, which were also evident in the sources and whereby writers sought material aid or advantage. These are categories which, as noted above, are not explicitly recognised in medieval theory, although this in itself does not argue against our ability to detect such relationships, and the concepts of ‘affective’ and ‘instrumental’ friendships were to become an important part of the analysis of medieval friendship. In effect, while Southern had concluded that affective relationships were not semantically distinguished from other types in the written sources, McGuire sought to show that they could be. Such linguistic or semantic approaches, exploring the degree to which it is possible to determine genuine emotion or personal feelings in the light of linguistic and genre conventions, have been refined and developed as researchers have attempted to further our understanding of the relationship between language and affectivity (e.g. Canatella 2007; DeMayo 2007).

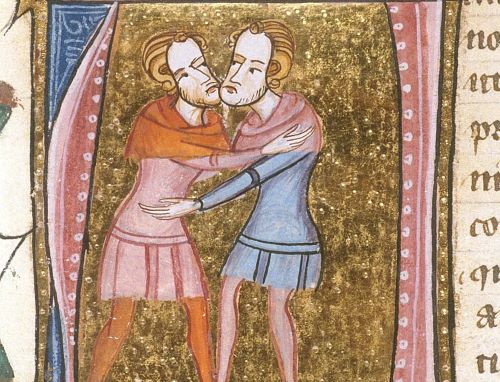

By contrast, C. Stephen Jaeger identified friendship as part of a wider tradition of love which was primarily public, was related to outward behaviour rather than inner feelings, was ethical not romantic, and had a social function in relation to honour and reputation. This ‘ennobling love’ existed distinctly from ideas about erotic or romantic love and dominated ancient and medieval discourses, as romantic or erotic love dominates the modern (Jaeger 1999). Both can be genuine and engage the emotions, and to take private emotional compatibility as definitive of genuine love or friendship is not to recognise a universal human experience but to impose a modern idealising discourse. Similarly, Gillian Knight’s semantic analysis of one of the most extensively studied and debated correspondences of the Middle Ages, that between Bernard of Clairvaux, the leading spokesman of the Cistercian Order, and Peter the Venerable, abbot of Cluny and head of Europe’s largest monastic congregation, takes the letters not as simple documents of a personal relationship but as strategic manipulations of the literary tradition of friendship whereby public and institutional conflicts were mediated through a language of private friendship (Knight 2002). The relations and rivalries between these two men and their orders have long been seen as dominating the religious politics of the twelfth century and Knight’s study effectively countered the traditional view that this was simply a case of private or personal feelings spilling out and influencing politics.

The concepts of instrumentality and affectivity have also been further refined. Historians had tended not to use the original concept, developed in the transactional analysis approaches of sociologists in the 1960s, which defined transactions between those involved in relationships as either communicative (exchanges of information) or instrumental (exchanges of goods and services), but rather to characterise whole relationships as affective or instrumental (an exception is Mullett 1997). The notion of a purely affective sphere of friendship existing outside, or independently of, other social contexts such as shared interest, common economic experience or allegiance, had been questioned by sociologists since Granovetter’s early, seminal studies of embeddedness (e.g. Granovetter 1985). Nevertheless, the recognition that bonds which may originate in ‘instrumental’ contexts, such as political allegiances or professional cooperation, can engender genuine affections, has only recently begun to influence historical analyses of friendship (see Jaeger 1999; Saurette 2005; Haseldine 2011). The same point has been made about exclusively or primarily textual relationships, such as exchanges of letters with little or no basis in personal acquaintance (Saurette 2010b; cf. ‘textual emotions’ in Mullett 2003, p.72).

It has also been shown that not all affectionate or intimate relationships were described as friendships in formal epistolary or diplomatic contexts, while many bonds which were not personally close were so-described (Haseldine 2006, pp. 249-53; 2011, p.257). The evidence thus indicates a more complex, non-exclusive dynamic between affectivity and instrumentality in historically documented relationships. Furthermore, and as in any society, most individual relationships were multiplex (e.g. Mullett 1988; 1997, pp.164-6), involving more than one source of obligation, where, for example, kin might also be allies, while most networks of formal friendship were also only one of a number of overlapping networks in which an individual or institution might participate and which were often articulated in the same or similar language as friendship (e.g. Ysebaert 2001, pp.436-51). These included patronage and kinship, but also very important in relation to friendship were master-pupil or intellectual relationships (e.g. Mews and Crossley eds. 2011; Grünbart 2005) and monastic confraternities, prayer associations and commemoration agreements (e.g. Althoff 1992; Jamroziak 2005, pp.203-18).

Historians have thus identified the language of friendship as evidence of effective bonds in all of the different contexts in which it is encountered, and as a meaningful, not a clichéd or empty, language simply because it does not reflect close personal intimacy. It has been seen to function as a language of inclusion, articulating and promoting group or institutional identity in ways which transcended simple instrumental strategies. The ethical norms it conveyed were in effect internalised by actors and affected their actions and their emotions, forming a currency of political discourse by which to critique behaviour and which was therefore effective beyond the sphere of personal likings. This applied whether the ideals were honoured or betrayed in any particular instances, and in this respect it functioned like other shared ideologies in other periods (Haseldine 1994). Furthermore, if the language were empty, and its use transparent, it could not have functioned socially in the specific ways evident in the sources, mediating honour and prestige (Jaeger 1999, pp.19-24, 150-4). More recently, Marc Saurette has developed the idea of affective strategies, manipulations, for political and institutional ends, of a love which was grounded in an emotional engagement which was genuine but which arose from collective or institutional identity, applying to the Cluniac monastic congregation Barbara Rosenwein’s concept of ’emotional communities’ (Saurette 2005, pp.27-168; cf. Rosenwein 2002).

Historians have thus identified the language of friendship as evidence of effective bonds in all of the different contexts in which it is encountered, and as a meaningful, not a clichéd or empty, language simply because it does not reflect close personal intimacy. It has been seen to function as a language of inclusion, articulating and promoting group or institutional identity in ways which transcended simple instrumental strategies. The ethical norms it conveyed were in effect internalised by actors and affected their actions and their emotions, forming a currency of political discourse by which to critique behaviour and which was therefore effective beyond the sphere of personal likings. This applied whether the ideals were honoured or betrayed in any particular instances, and in this respect it functioned like other shared ideologies in other periods (Haseldine 1994). Furthermore, if the language were empty, and its use transparent, it could not have functioned socially in the specific ways evident in the sources, mediating honour and prestige (Jaeger 1999, pp.19-24, 150-4). More recently, Marc Saurette has developed the idea of affective strategies, manipulations, for political and institutional ends, of a love which was grounded in an emotional engagement which was genuine but which arose from collective or institutional identity, applying to the Cluniac monastic congregation Barbara Rosenwein’s concept of ’emotional communities’ (Saurette 2005, pp.27-168; cf. Rosenwein 2002). categories, whereby some ‘informal’ friends were also formally acknowledged and others evidently were not (Haseldine 2006, pp.251-3). It would also allow us to determine the degree to which affectionate relationships contributed to larger networks, and to identify which formally acknowledged friendships were also based in emotional ties, even if, as recent network studies suggest, these were a minority.

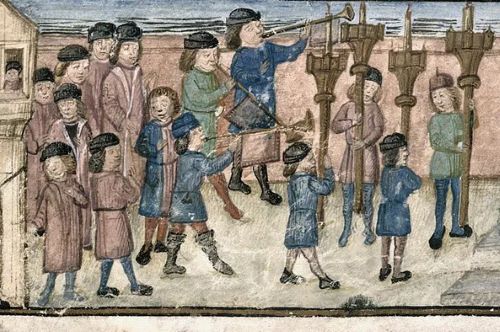

Meanwhile, the study of political friendship in the Middle Ages has grown rapidly. A number of earlier contributions had identified circles of friendship as effective in promoting political agendas at the highest levels (e.g. Robinson 1978; Feld 1985). In the 1990s friendship became prominent in the debates about the nature of the ‘state’ in the Middle Ages. Older models of medieval polities as comprising multiple dyadic bonds with few or no constitutional or overarching legal structures – such as the ‘feudal pyramid’ of early twentieth-century English historiography, the French ‘mutation féodale’, or the German Personenverbandsstaat – had already given way to an appreciation of more complex corporate, collective and legal structures, including friendship. Gerd Althoff’s analyses of gesture and ritual language in the communication of power, and the Spielregeln (‘rules of the game’) which governed this process, crucially identified friendship as one of a number of bonds employing ritual and gesture in carefully rehearsed and performed acts of communication intended to convey unambiguous messages to onlookers, and not unself-conscious actions revealing of individual psychologies. As such friendship was constitutive of political order (Althoff 1990; 1999). There is now a wellestablished historiography of political friendship for many regions and polities of medieval Europe (e.g. Sigurðsson 1999; Garnier 2000; van Eickels 2002; Oschema 2011). Much of the work in this area has promoted an approach to friendship as a separate category of social and political relations, with its own distinct articulation, in contrast to a long tradition of anthropological research, dating back as far as Mauss’s seminal essay on gift-exchange (Mauss 1923), which tended to see it as part of a matrix of inextricable and unself-conscious instrumental exchanges constitutive of pre-market social organisation (see Konstan 1997, pp.3-6).

In 2005 Margaret Mullett, whose early work had proposed a fundamental re-evaluation of friendship in the Byzantine Empire (Mullett 1988), identified a ‘new agenda’ emerging in medieval studies, concerned with the structural role of friendship in the formation of networks of allegiance and shared interest (Mullett 2005). The studies associated with this approach (see below, Analyzing medieval friendship networks p. 8-15), in some cases themselves inspired directly by Mullett’s methods, have sought to understand the processes of network formation and its impact on routine political activity beyond the high political or diplomatic sphere. A primary concern has been to interpret the language of friendship used in the sources by correlating it to the social, personal, institutional and political contexts in which it was deployed. Such studies to date have focussed on leading members of the monastic orders or of ecclesiastical élites, where the documentation is fullest, and especially on letter collections. A key feature of these approaches has been to attempt the analysis of whole networks and routine relations rather than to focus on the much smaller number of very well-documented relationships evidenced in richly expressive but atypical sources which have provided much of the evidence for the ideals of friendship.

The Nature of the Evidence and Methodology

Medieval friendship relationships are evidenced in many different types of source including letters, charters, legislative texts, treaties and agreements, records of cooperative groups (including sworn associations, prayer associations and confraternities), chronicles and other historical narratives, verse, hagiography, and philosophical and theological treatises. These each present particular source-critical questions but it is also possible to identify a number of general analytical problems which have been the focus of recent studies.

- The evidence relates predominantly to élite groups, with ecclesiastical and monastic figures disproportionately represented. There is evidence of friendships among non-élite groups, such as the conjurationes (sworn associations) discussed by Althoff, but these are known largely from indirect evidence concerned with their control or suppression (Althoff 1990, pp.119-33).

- The evidence is often preserved in self-consciously literary sources created at some later date. Letters are a case in point. Potentially they offer some of the richest evidence for friendship, simultaneously articulating the ideals of friendship and functioning as the medium for its cultivation. The overwhelming majority, however, survive not as originals but in the context of letter collections, highly selective literary enterprises often compiled late in an author’s life, or posthumously by former associates, and constructed deliberately to project a particular image of the author for posterity in ways now very well understood (see Constable 1976; Haseldine 1997; Ysebaert 2009). Such sources were drastically selective, preserving typically an average of five or fewer pieces of correspondence per year. Further, the principles of selection governing their compilation were rarely made explicit; they often privilege high-status connections or preserve examples of the writer’s erudition.

- References to, or invocations of, friendship are often governed by genre conventions which must be taken into account in assessing the nature of the relationships concerned. Letters again have posed particular problems: for example, a profession of friendship to a stranger by letter may be only a conventional accompaniment to a request for aid. Letter writing was also considered one of the formal rhetorical arts and was the subject of expository manuals which included model letters for different occasions; the ways in which writers used such manuals, and indeed the whole question of the influence and spread of this, the ars dictaminis (or dictamen), has yet to be fully explored (Ysebaert 2005, pp.296-300). Consequently, the study of epistolography, a well-developed field in its own right, has also become a central concern for the study of medieval friendship, and its relation to friendship has been discussed in detail (see Knight 2002, pp.1-23; Ysebaert 2009). For these reasons, the sources tend to stress ‘formal’ rather than ‘informal’ friendships, preserving selected examples of exemplary relationships, with reference to ideal friendship, and with the reputation of the author in mind. Friendships with virtuous strangers, for example, were often prioritised, and there is even one possible example of a posthumously invented friendship, that between Bernard of Clairvaux and one of his later biographers, where a forged letter may have been inserted into Bernard’s letter collection after his death to enhance the biographer’s credentials and authenticate his testimony (Bredero 1996, pp.102-118).

- For these reasons, the sources tend to stress ‘formal’ rather than ‘informal’ friendships, preserving selected examples of exemplary relationships, with reference to ideal friendship, and with the reputation of the author in mind. Friendships with virtuous strangers, for example, were often prioritised, and there is even one possible example of a posthumously invented friendship, that between Bernard of Clairvaux and one of his later biographers, where a forged letter may have been inserted into Bernard’s letter collection after his death to enhance the biographer’s credentials and authenticate his testimony (Bredero 1996, pp.102-118).

- Finally, it is difficult to establish to what extent different writers, sources and genres employed a shared or common definition of friendship or made similar assumptions about its nature. A researcher cannot, of course, as with living subjects, define friendship for the purposes of a particular study or elucidate by discussion with actors their understandings of the concept in order to compare the multiple and overlapping definitions of friendship current in medieval, as in any, society.

The medieval evidence thus presents, firstly, a number of problems related to incomplete data, and secondly, a particular problem of basic definition. Medievalists have in response developed a two-part methodology comprising, as expounded by Mullett, firstly the detection of relationship and secondly the detection of network (Mullett 2003; cf. 1988, pp.21-2). The first of these attempts to establish a working definition of friendship as it occurs in the sources, the second to analyse the structures and networks created by these bonds. These two stages are postulated to be logically sequential on the grounds that it is not possible to evaluate networks of friendship unless we understand to what sorts of relationship the terms we translate as ‘friendship’ refer.

Analysing Medieval Friendship Networks

When it comes to defining friendship, not only do we have no explicit and unambiguous definition common to all of the sources, but we also lack a complete picture of the activities and obligations associated with it. Many obligations, activities and exchanges have been observed to be associated with friendship (see below p. 12-13 s.iii), but we do not know either how consistently these activities, or any combinations of them, were associated with friendship bonds, or whether evidence for them can be taken as evidence of an acknowledged bond of friendship when they occur in the sources with no associated vocabulary of friendship. It is thus not possible to take as a starting point a coherent definition of friendship as defined by the researcher according to a particular model. Rather, the individual terms, activities and exchanges associated with those relationships which are termed friendships in the sources must be identified and correlated to build up a working knowledge of what the relationship involved in practice.

This method can employ both evidence internal to the sources, such as references to gift exchange or claims for material support made explicitly in the name of friendship, and external evidence, where there is, for example, evidence in one context of political cooperation between individuals who are elsewhere, or at other times, described as friends or refer to one another as friends. In addition, factors such as common institutional affiliations (membership of the same monastic community or order, for example), relative social status, and evidence for frequency of personal contact or proximity must be taken into account where the evidence permits. It is critical that no presumptions about the possible emotional basis of the relationships be made at this stage as this would create a circular argument for the reasons set out above. The key to defining friendship lies in tracing the complex connections between the use of the vocabulary of friendship, the attributes of the relationship, including the obligations, activities and exchanges associated with it, and the types of persons or institutions typically included. Once a practical definition of friendship as it was used has been established it should then be possible to analyse the networks and structures created by such bonds.

This method can employ both evidence internal to the sources, such as references to gift exchange or claims for material support made explicitly in the name of friendship, and external evidence, where there is, for example, evidence in one context of political cooperation between individuals who are elsewhere, or at other times, described as friends or refer to one another as friends. In addition, factors such as common institutional affiliations (membership of the same monastic community or order, for example), relative social status, and evidence for frequency of personal contact or proximity must be taken into account where the evidence permits. It is critical that no presumptions about the possible emotional basis of the relationships be made at this stage as this would create a circular argument for the reasons set out above. The key to defining friendship lies in tracing the complex connections between the use of the vocabulary of friendship, the attributes of the relationship, including the obligations, activities and exchanges associated with it, and the types of persons or institutions typically included. Once a practical definition of friendship as it was used has been established it should then be possible to analyse the networks and structures created by such bonds.

This stage of the detection of relationship is necessary because of the lack of a secure and coherent definition of friendship in the sources, as noted above, which could form the basis for the collection of relational data (or, to put it again in network-analytical terminology, because direct sociometric choice data (Scott 2000, p.42) is not available from medieval sources). If this method eventually permits a working definition of friendship, or of formal friendship, then it should be possible, as a next stage, to move on to construct a relational data set in which friendship, defined thereby and thus able to be treated as one distinct type of relationship, could be included alongside other relationships, such as patronage, kinship, allegiance, confraternity and so forth, and the patterns and structures of these relationships investigated using network-analytical techniques.

Finally, some of the standard manipulations of relational data, using what are termed adjacency matrices (Scott 2000, pp.38-49), could also resolve the key questions noted above, of multiplex relationships and of multiple networks, which are very difficult to assess discursively. Thus we could determine the degree to which friends in general tended also to be bound simultaneously by other ties, by deriving case-by-case matrices. Such matrices would present all of the possible relationships and, for each relationship, the numbers of pairs of actors who were involved both in that relationship and, by turn, in each of the other types of relationship. This would tell us which types of relationship were commonly held simultaneously and which were more commonly mutually exclusive, whether, for example, it was either common or rare for kin also to be formal friends, or allies, or for allies also to be kin, and so forth. We could also determine the ways in which individual actors’ different networking activities intersected or were interdependent, by deriving affiliation-by-affiliation matrices. Here the matrices would present all of the individual actors and allow the researcher to determine how many different relationships each pair shared, for example, whether most friends or only a few were also allies, or were also both allies and kin, or simultaneously allies, kin and confrères, etc., and how common such multiple bonds were. This could tell us the degree to which actors built up their networks in separate or in overlapping circles of acquaintance and would give a far more precise idea of the relative importance and function of friendship within an actor’s full range of social and political relations.

In fact, the first major attempt systematically to detect medieval relationships used transactional content analysis, long-established in the study of modern friendships before the development of the social network analytical methods described by Scott (Mullett 1997, applying the methods expounded in the seminal Boissevain 1974). However, both approaches, critically, avoid assigning relationships to pre-existing categories such as ‘true’ or ‘false’ or ‘affective’ or ‘instrumental’, looking instead for patterns of actions and language which can be seen to constitute similar relationships. Something similar to the use of variable analysis of attribute data to define relationships, followed by assessments of the patterns of the relationships so-revealed, has underpinned a number of recent studies. The first of this type, all using letter collections, proposed and correlated various measures such as relative social status, geographical location, and choice of vocabulary (McLoughlin 1990), types of epistolary relationship, and letter function (Haseldine 1994), and types of relationships (‘genres de relation’) between correspondents or third parties named in letters (Ysebaert 2001). These studies, each of which applied some of the same measures used in the preceding ones for the most direct comparisons, were followed by others using further correlations of language use, letter function and social context (e.g. Saurette 2005; 2010a; Haseldine 2006; 2011). One important finding of these studies has been that the use of the vocabulary of friendship can often be determined not by the nature of the underlying relationship between the correspondents but rather by the function of the letter, making the detection of relationship yet more complex.

A particular problem for network analysis in this area is that the nature of most medieval sources affects the completeness of the relational data which can be derived even more so than that of the attribute data. Most medieval sources are so constructed that they produce evidence which is, in network-analytical terms, ego-centred: letter collections, for example, are almost always collections of senders’ letters, in many cases lacking replies or letters received, while histories and chronicles often focus on the interests of one community or individual and were often the products of particular institutions whose interests they also promoted. Another problem is that of what we might term ‘silent actors’: there is evidence that friendship bonds were often only invoked in writing in times of need or crisis, suggesting that many more, if not most, actual friendships have gone unrecorded, while those living in close proximity may also have cultivated many more friendships without producing written records. As a result, we cannot see networks of potential communication channels, only those (and indeed only a few of those) which were actually acted upon. Thus, whole network data is usually unattainable and this limits our ability to analyse certain structural features of networks, such as cliques and clusters or density and centralisation, which are important in social network analysis (Mullett 1997, pp.163-72).

There have to date been relatively few applications of network analysis using relational data, as opposed to qualitative descriptions of circles or groups of friends, in medieval studies. Mullett’s use of transactional content analysis, with the associated conceptual vocabulary of zones and orders of relationship, was pioneering (Mullett 1997), and Grünbart has presented some sociometric star analyses of Byzantine letter collections, revealing the importance of teacherpupil relationships and of literary patronage in Byzantine political culture and noting the possibilities for further comparative analyses of similar collections (Grünbart 2005). There have been a number of analyses and descriptions of networks outside the ambit of friendship (mostly concerning patronage) which there is not space to list here, but the best discussion and example of network analysis, including the application of UCINET, the most effective software programme available for use by non-mathematicians, using pre-modern sources, although not specifically concerned with friendship, is Giovanni Ruffini’s study of the Oxyrhyncos papyri and related material (Ruffini 2008).

A Provisional Model

Overview

Research on friendship networks is thus emerging as a field distinct from the related studies of the literary tradition of friendship, of diplomatic friendship, and of particular relationships and their emotional content, and is characterised by attempts to analyse language use and practical interactions across whole networks. This has begun to reveal a number of features of friendship as a distinct category of social and political relations. These can conveniently be discussed in terms of i) source-critical, genre and semantic considerations; ii) the choice of friends; iii) practicalities of friendship relationships; iv) the broader purposes of the cultivation of friendships; and v) networks and structures.

Source-Critical, Genre, and Semantic Considerations

Friendship was articulated through a shared language which related to a distinct intellectual tradition of political friendship, and through a common ritual language intended to convey explicit messages. This language was not empty, meaningless or clichéd, for the reasons discussed above, but constituted a common ethical framework for mediating political and social relationships; it also involved a genuine emotional engagement but one which was not erotic or romantic (see Mullett 1988; Althoff 1990; Haseldine 1994; Jaeger 1999; Knight 2002; Saurette 2005; 2010b).

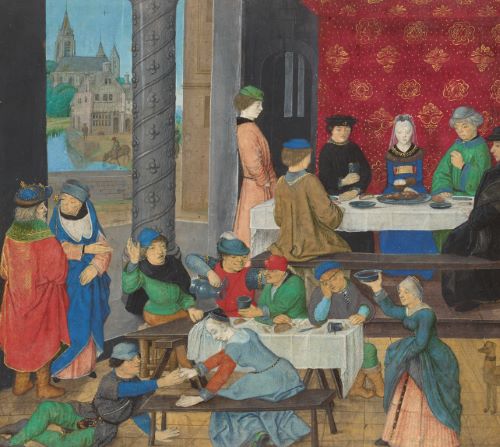

The sources can appear to reveal distinct spheres, or even cultures, of friendly interaction. These include diplomatic friendship, with a repertoire of gesture, ritual and physical contact; a literary, predominantly ecclesiastical bond formally cultivated through letters and with explicit reference to the classical literary tradition; sworn associations of allies, often mediated through monastic or ecclesiastical institutions in the form of prayer associations or through guilds, which consolidated local or regional mutual interest groups; and companionships in arms and other solidarities related to aristocratic military or ‘chivalric’ culture, commonly reflected in fictional relationships in poetic sources. However, these distinctions may be artefacts of the literary genres in which they are reflected and there are strong grounds for seeing friendship as a common élite or aristocratic culture (Jaeger 1999, pp.4-7). This is often concealed by the selective nature of the sources in the ways discussed above, but there is evidence, for example, of monastic leaders cultivating lay allegiances (e.g. Saurette 2010a) and of chivalric portrayals of friendships drawing on classical ideals (Legros 2001, pp.101-136).

What may be termed ‘formal’ friendship, in the sense suggested above, is not semantically distinguished from affective or other close bonds in any simple or obvious way. Firstly, affectionate language was commonly used to relatively distant acquaintances or to strangers (Southern 1963, pp.67-76; McLoughlin 1990), while intimates or kin were often excluded from formal designation as friends, or addressed as friends only at times of crises for the relationship or in the same political contexts as more personally distant acquaintances (Haseldine 1994; 2006; Mullett 1997, pp.197-222). Secondly, there is no close correlation between friendly or affectionate tone and uses of friend as a term of address (McLoughlin 1990; Haseldine 1994).

The uses of various terms usually translated as ‘love’ and which convey a range of nuance and meaning (e.g. amor, caritas or dilectio in Latin), and of the many common affectionate terms of address (e.g. carissimus – ‘dearest’ – in Latin) are complex and overlap with the use of terms translated as friend. The conceptual and semantic relationships between friendship and these various concepts of love are fundamental to the interpretations of medieval friendship discussed above and have also been an important part of many network analyses (e.g. McLoughlin 1990; Haseldine 1994; Knight 1997; Goetz 1999; Ysebaert 2001; 2005; Haseldine 2010; 2011)

The Choice of Friends

Friendships were largely exclusive in terms of social status and gender. The majority of those addressed as friends in letters were of equal status to, or higher than, the writers (e.g. McLoughlin 1990; Mullett 1997, pp.197-201); inclusion of those of lower-status could be a strategy to demonstrate humility or piety and the stated reason for the friendship was often the piety of the recipient (Haseldine 2010, pp.371-2). Male religious and ecclesiastical leaders extended friendship predominantly to fellow religious or ecclesiastics, and, with only very few exceptions, to men (Haseldine 1994; Mullett 1997, pp.197-201; Ysebaert 2001). The terms on which women were admitted to predominantly male circles of friendship is a critical question for further research and central to developing understandings of friendship (see Sandidge 2010).

Friendships could be formally requested, sometimes of strangers and sometimes via third-party mediators; personal acquaintance was only one, and not necessarily the most common, route in to formal friendship (Haseldine 1994, pp.252-8; ed. 1999, p. xix).

Friendships were routinely contracted between individuals and communities, most commonly monasteries (Haseldine 1993; Jamroziak 2005, pp. 131-202); in some cases such friendships were explicitly identified as institutional, as for example with those referred to by Peter the Venerable as ‘friends of Cluny’ (Saurette 2010a).

Some friendships could be inherited, such as institutional friendships where an abbot assumed a predecessor’s friendships, or individual, where, for example, friendship was requested of a newly elected bishop explicitly as a continuation of a friendship with his predecessor (Haseldine 2010, pp.375-7).

Practicalities of Friendship Relationships

Friendship involved practical mutual obligations but these were not always explicitly referred to in the sources (McLoughlin 1990, p.174). These included support or mediation in conflicts and disputes (e.g. Jamroziak 2005, pp.131-63; Saurette 2010a); furnishing information or advice (McLoughlin 1990; Mullett 1997 pp. 201-22; Ysebaert 2001); supporting the same party or cause in major political disputes (e.g. Robinson 1978; Feld 1985; McLoughlin 1990); or giving assistance in the composition and dissemination of writings, including polemical writings and those promoting corporate or institutional interests (e.g. Haseldine 2006, pp.271-2).

The cultivation or maintenance of friendships beyond the demands of immediate aid (the ‘servicing’ of relationships (Mullett 1997, p.204)) involved exchanges of material and spiritual benefits. In some contexts, gift exchange was central to friendship (Mullett 1997, pp.201-22; Sigurðsson 1999; Grünbart ed. 2011). In ecclesiastical and monastic contexts the idea of the gift was often translated into the exchange of spiritual benefits, including undertakings to offer prayers for the friend (a practice related to the important social institutions of confraternity, commemoration and prayer association noted above), and the exchange of letters of consolation or spiritual exhortation; the exchange of letters itself is also commonly articulated as a duty of friendship and the letter seen as a gift (e.g. Mullett 1997, pp.201-222; Saurette 2005, pp.45-9). Joking exchanges and mock rebukes for lapses in the duties of friendship were also common (Pepin 1983; Mullett 1997, pp.201-22).

Friends commonly petitioned one another for third parties or recommended others for patronage or advancement. The third-party beneficiaries were usually those in unequal relationships to the writers, such as junior members of their institutions, clients or dependents, or kin of lower status; here friendship can be seen to intersect with patronage (e.g. Mullett 1997, pp.221-2; Ysebaert 2001). Third parties also appealed to known friends of adversaries or judges for assistance in disputes even where the friends had no formal jurisdiction (Haseldine 2010, pp.383-4).

The Broader Purposes of the Cultivation of Friendships

Friendship served to facilitate contact: overtures of friendship functioned to establish new contacts (e.g. Haseldine 1994, pp.254-7; Ysebaert 2005, pp.285- 8), while affirmations of friendship served as an enabling discourse in dispute resolution and to address crises in existing relationships, allowing those involved to raise contentious or sensitive matters under the guise of friendly communication (Haseldine 1993; Knight 2002).

Friendships between monastic leaders could likewise mediate the relationships between their institutions or orders (Jamroziak 2005, pp.131-63), with ostensibly private friendships between leaders allowing them to raise matters of institutional or political conflict (Haseldine 1993; Knight 2002; cf. Saurette 2005, pp.55-128).

Appeals to friendship were used to legitimate demands or requests (Knight 2002; Saurette 2005, pp.67-74); the invocation of friendship in these contexts, however, could also be a genre convention and not necessarily a reflection of an existing obligation (Ysebaert 2001).

Friendship also functioned to establish or maintain bonds of shared interest where there was no immediate need or conflict, acting as a language of inclusion to establish group formation and identity (Haseldine 1994; Jamroziak 2005, pp.131-63; Saurette 2010a). At the same time, selective use of friendship language could serve to differentiate friends or to exclude others, thus functioning to display power (Saurette 2010b).

Friendship was also used to promote institutional interests and to propagate political or corporate ideals in the context of wider political agendas (e.g. Robinson 1978; Feld 1985; Saurette 2005, pp.27-54; 2010a). Letters of conversion or vocation are a case in point, where ostensibly private friendly letters exhorting monastic vocations or offering support in spiritual crises functioned to promote the claims and ideals of a particular monastic order in a period of intense competition among the orders (Knight 1997; Haseldine 2011). In some cases the use of the vocabulary of friendship was restricted to very specific contexts to the exclusion of others: in the case of Bernard of Clairvaux, for example, these included appeals to the papacy, the promotion of monastic reform agendas and literary production concerned with the projection of institutional ideals, while many vital institutional and personal supporters were not addressed as friends (Haseldine 2006).

Institutional friendships also functioned locally to mediate relations between religious institutions and the lay nobility, bridging lay-religious divisions under a language of Christian harmony and facilitating the mutual exchange of benefits (Saurette 2010a, p.305; cf. Jamroziak 2005, pp.131-202).

Two themes emerge from this. Firstly, the use of friendly language and the cultivation or invocation of friendships are determined by the purposes behind the communication – for example, conflict resolution, forming bonds of common interest, exerting soft or diplomatic power, or promoting institutional interests – and not by the nature of the underlying relationships. No one type of relationship, intimacy, allegiance, institutional affiliation or any other sort, is consistently included in or excluded from friendship, and with most authors only some intimates are called friends, and then often in the same contexts as more distant acquaintances. Secondly, the corporate nature of many friendships, and the many permutations of bonds between communities and between communities and individuals, suggest that collective bonds were integral to friendship not occasional exceptions or merely metaphorical extensions of friendly language. No one type of bond, affectionate or pragmatic, personal or political, collective or individual, is uniquely linked to formal friendship. Interpretations based primarily on any of these cannot therefore satisfactorily account for the evidence without accepting large numbers of exceptions and anomalies or by assuming that the language is being used arbitrarily.

Two themes emerge from this. Firstly, the use of friendly language and the cultivation or invocation of friendships are determined by the purposes behind the communication – for example, conflict resolution, forming bonds of common interest, exerting soft or diplomatic power, or promoting institutional interests – and not by the nature of the underlying relationships. No one type of relationship, intimacy, allegiance, institutional affiliation or any other sort, is consistently included in or excluded from friendship, and with most authors only some intimates are called friends, and then often in the same contexts as more distant acquaintances. Secondly, the corporate nature of many friendships, and the many permutations of bonds between communities and between communities and individuals, suggest that collective bonds were integral to friendship not occasional exceptions or merely metaphorical extensions of friendly language. No one type of bond, affectionate or pragmatic, personal or political, collective or individual, is uniquely linked to formal friendship. Interpretations based primarily on any of these cannot therefore satisfactorily account for the evidence without accepting large numbers of exceptions and anomalies or by assuming that the language is being used arbitrarily.

Networks and Structures

While we now have a good deal of research on memberships of friendship networks, and their modes of operation and impacts, we know far less about their internal structures, including specific features central to network analysis such as density, centrality or degrees of connectedness. This arises in part from the nature of the evidence, which produces data which is both incomplete and ego-centric, as discussed above.

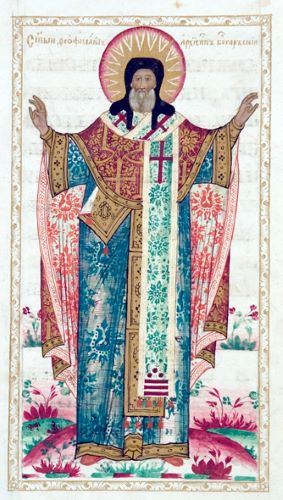

In the most comprehensive structural network study to date, based on the letters of the Byzantine archbishop Theophylact of Ochrid, Mullett demonstrated that the author was not central to the key networks evidenced but rather was accessing networks centred on the imperial capital from a marginal position to maintain influence, gather information and pursue patronage (Mullett 1997, pp. 196-201). This shows what can be achieved through the analysis of specific network features, as opposed to qualitative description, when surviving egocentred source material can make an author appear deceptively central to political activity.

Given the inherent limitations of the data which can be derived from medieval sources, and the common lack of evidence for whole networks, the most promising direction for research may be to compare the profiles of separate networks (on the basis of social and functional features of the sorts discussed above), and to analyse those structural features which can best be studied, and then to make comparative studies based on these analyses (cf. Grünbart 2005).

Conclusions

Medievalists have identified friendship as a formal bond which functioned in group formation, conflict resolution and diplomacy at individual and corporate levels. A lot has been established about its cultivation, operation and impact, while less is known about the structures of the networks themselves and their interconnections with other networks. Models of friendship based on particular types of relationship, whether affectionate, spiritual, allegiance or any other, cannot account coherently for the evidence of the incidence of friendship, but trust building offers an explanatory framework which can accommodate this evidence, accounting for the range of relationships accorded the status of friendships. This is specifically because it can account both for the diverse social and emotional origins of the relationships and for their common functions and the aims they promote.

What this language reflects is not a cynical or empty manipulation of ‘genuine’ personal bonds, but rather an equally genuine and emotionally engaging type of relationship, but one which is neither erotic nor romantic and which has been variously characterised as public, ethical, formal or ennobling. While this coexisted with a human experience of romantic or affective friendship, it was this other friendship which was the object of the dominant medieval ethical discourse. Conversely, modern discourses have elevated the private and affectionate to the status of emotionally genuine and treated political friendship with suspicion. This has served to emphasise discontinuities with pre-modern experience. In the modern context the recognition of a genuine and emotionally engaging but political, not romantic, friendship is only now emerging in the research literature. The two histories, of affectionate or romantic friendship and of political or trust-building friendship, do not preclude one another but changes in the uses of language and in the attribution of genuineness and falsity over time can obscure the common experiences behind each. This is not to propose an artificial or exaggerated notion of continuity across very different periods and cultures, but rather to suggest that a model of medieval friendship based on its practicalities and functions, rather than its theoretical or ethical framing, can offer a more promising basis for comparison with the sorts of modern social structures and networks now being identified as, or associated with, friendship.

References

- Althoff, G. (1990) Verwandte, Freunde und Getreue. Zum politischen Stellenwert der Gruppenbindungen im früheren Mittelalter. Darmstadt, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Althoff, G. (1992) Amicitiae und Pacta: Bündnis, Einung, Politik und Gebetsgedenken im beginnenden 10. Jahrhundert. Hannover, Hahnsche Buchhandlung.

- Althoff, G. (1999) Friendship and Political Order. In Haseldine (ed.) Friendship in Medieval Europe. Stroud, Sutton Publishing.

- Boissevain, J. (1974) Friends of Friends. Networks, Manipulators and Coalitions. Oxford, Blackwell.

- Bredero, A. H. (1996) Bernard of Clairvaux: Between cult and history. Edinburgh, T&T Clark.

- Burton, P. J. (2011) Friendship and Empire: Roman Diplomacy and Imperialism in the Middle Republic (353-146 BC). Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Canatella, H. M. (2007) Friendship in Anselm of Canterbury’s Correspondence: Ideals and Experience. Viator, 38, 351-367.

- Cassidy, E. G. (1999) ‘He who has friends can have no friend’: Classical and Christian perspectives on the limits of friendship. In Haseldine (ed.) Friendship in Medieval Europe. Stroud, Sutton Publishing.

- Castigilione, D., Van Deth, J. W. and Wolleb, G. (eds.) (2008) The Handbook of Social Capital. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- Classen, A. and Sandidge, M., (eds.) (2010) Friendship in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Age: Exploration of a Fundamental Ethical Discourse. Berlin, De Gruyter.

- Constable, G. (1976) Letters and Letter Collections. Turnhout, Brepols.

- DeMayo, C. (2007) Ciceronian Amicitia in the Letters of Gerbert of Aurillac. Viator, 38, 319-337.

- Descharmes, B., Heuser, E. A., Krüger, C. and Loy, T. (eds.) (2011) Varieties of Friendship. Gottingen, V&R Unipress.

- Devere, H. (2011) Introduction. The Resurrection of Political Friendship: Making Connections. In Descharmes, B., Heuser, E. A., Krüger, C. and Loy, T. (eds.) (2011) Varieties of Friendship. Gottingen, V&R Unipress.

- Feld, H. (1985) Die europäische Politik Gerberts von Aurillac: Freundschaft und Treue als politische Tugenden. In Gerberto, scienza, storia e mito. Atti del Gerberti Symposium (Bobbio 25-27 Iuglio 1983). Piacenza, A. S. B. Bobbio.

- Garnier, C. (2000) Amicus amicis – inimicus inimicis. Politische Freundschaft und fürstliche Netzwerke im 13. Jahrhundert. Suttgart, Anton Hiersemann.

- Goetz, H.-W. (1999) ‘Beatus homo qui invenit amicum.’ The Concept of Friendship in Early Medieval Letters of the Anglo-Saxon Tradition on the Continent (Boniface, Alcuin). In Haseldine, J.P. (ed.) Friendship in Medieval Europe. Stroud, Sutton Publishing.

- Granovetter, M. (1985) Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91, 481-510.

- Grünbart, M. (2005) ‘Tis love that has warm’d us. Reconstructing networks in 12th-century Byzantium. Revue Belge de philologie et d’histoire, 83, 301-313.

- Grünbart, M. (ed.) (2011) Geschenke erhalten die Freundschaft: Gabentausch und Netzwerkpflege im europäischen Mittelalter. Münster, LitVerlag.

- Haseldine, J. P. (1993) Friendship and Rivalry: The Role of Amicitia in Twelfth-Century Monastic Relations. Journal of Ecclesiastical History, 44, 390-414.

- Haseldine, J. P. (1994) Understanding the language of amicitia. The friendship circle of Peter of Celle (c.1115-1183). Journal of Medieval History, 20, 237-260.

- Haseldine, J. P. (1997) The Creation of a Literary Memorial: The Letter Collection of Peter of Celle. Sacris Erudiri, 37, 333-379. Haseldine, J. P. (ed.) (1999) Friendship in Medieval Europe. Stroud, Sutton Publishing.

- Haseldine, J. P. (2006) Friends, Friendship and Networks in the Letters of Bernard of Clairvaux. Cîteaux Commentarii Cistercienses, 57, 243-280.

- Haseldine, J. P. (2010) Monastic Friendship in Theory and in Action in the Twelfth Century. In Classen, A. and Sandidge, M., (eds.) Friendship in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Age: Exploration of a Fundamental Ethical Discourse. Berlin, De Gruyter.

- Haseldine, J. P. (2011) Friendship, Intimacy and Corporate Networking in the Twelfth century: The Politics of Friendship in the Letters of Peter the Venerable. English Historical Review, 126, 251-280.

- Jaeger, C. S. (1999) Ennobling Love: In Search of a Lost Sensibility. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Jamroziak, E. (2005) Rievaulx Abbey and its Social Context, 1132-1300. Memory, Locality and Networks. Turnhout, Brepols.

- Knight, G. R. (1997) Uses and Abuses of amicitia: the Correspondence between Peter the Venerable and Hato of Troyes. Reading Medieval Studies, 23, 35-67.

- Knight, G. R. (2002) The Correspondence Between Peter the Venerable and Bernard of Clairvaux: A Semantic and Structural Analysis. Aldershot, Ashgate.

- Konstan, D. (1997) Friendship in the Classical World. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Legros, H. (2001) L’Amitié dans les chansons de geste à l’époque romane. Provence, Publications de l’Université de Provence.

- Le Jan, R. (1995) Famille et pouvoir dans le monde Franc (viie -x e siècle). Essai d’anthropologie sociale. Paris, Publications de la Sorbonne.

- Lyon, F., Möllering, G. and Saunders, M. (eds.) (2012) Handbook of Research Methods on Trust. Cheltenham, Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Mauss, M. (1923) Essai sur le don. Forme et raison de l’échange dans les sociétés archaïques. L’Année sociologique, 1923-4.

- McLoughlin, J. (1990) Amicitia in Practice: John of Salisbury (c.1120-1180) and his Circle. In Williams, D. (ed.) England in the Twelfth Century, Proceedings of the 1988 Harlaxton Symposium. Woodbridge, Boydell, 165-181.

- McEvoy, J. (1999) The Theory of Friendship in the Latin Middle Ages: Hermeneutics, contextualization and the transmission and reception of ancient texts and ideas, from c. AD 350 to c.1500. In Haseldine, J.P. (ed.) Friendship in Medieval Europe. Stroud, Sutton Publishing.

- McGuire, B. P. (1988) Friendship and Community. The monastic experience 350-1250. Kalamazoo, MI, Cistercian Publications Inc. Mews, C. J. (2007) Cicero and the Boundaries of Friendship in the Twelfth Century. Viator, 38, 369-384.

- Mews, C. and Crossley, J. N. (eds.) (2011) Communities of Learning: Networks and the Shaping of Intellectual Identity in Europe 1100-1500. Turnhout, Brepols.

- Mullett, M. (1988) Byzantium: A friendly society? Past and Present, 118, 3-24.

- Mullett, M. (1997) Theophylact of Ochrid. Reading the letters of a Byzantine archbishop. Aldershot, Variorum Publishing.

- Mullett, M. (2003) The Detection of Relationship in Middle Byzantine Literary Texts: The case of letters and letter-networks. In Hörandner, W. and Grünbart, M. (eds.) L’épistolographie et la poésie épigrammatique: projets actuels et questions de méthodologie. Paris, Centre d’études byzantines, néohelléniques et sud-est européenes.

- Mullett, M. (2005) Power, relations and networks in medieval Europe. Introduction. Revue Belge de philologie at d’histoire, 83, 255-259.

- Nederman, C. J. (2007) Friendship in Public Life During the Twelfth Century: Theory and Practice in the Writings of John of Salisbury. Viator, 38, 385-397.

- Oschema, K. (2011) Falsches Spiel mit wahren Körpern. Freundschaftsgesten und die Politik der Authentizität im franko-burgundischen Spätmittelalter. Historische Zeitschrift, 293, 40-67.

- Pepin, R. E. (1983) Amicitia Jocosa: Peter of Celle and John of Salisbury. Florilegium, 5, 140-56.

- Robinson, I. S. (1978) The Friendship Network of Gregory VII. History, 63, 1-22.

- Rosenwein, B. (2002) Worrying about Emotions in History. American Historical Review, 107, 821-46.

- Ruffini, G. (2008) Social Networks in Byzantine Egypt. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Sandidge, M. (2010) Women and Friendship. In Classen, A. and Sandidge, M., (eds.) Friendship in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Age: Exploration of a Fundamental Ethical Discourse. Berlin, De Gruyter.

- Saurette M. (2005) Rhetorics of Reform: Abbot Peter the Venerable and the Twelfth-Century Rewriting of the Cluniac Monastic Project. PhD diss., Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Toronto.

- Saurette, M. (2010a) Peter the Venerable and Secular Friendships. In Classen, A. and Sandidge, M., (eds.) Friendship in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Age: Exploration of a Fundamental Ethical Discourse. Berlin, De Gruyter.

- Saurette, M. (2010b) Thoughts on Friendship in the Letters of Peter the Venerable. Revue Bénédictine, 120, 321-346.

- Schulte, P., Mostert, M. and van Renswoude, I. (eds.) (2008) Strategies of Writing: Studies on Text and Trust in the Middle Ages. Turnhout, Brepols.

- Scott, J (2000) Social Network Analysis: a handbook, 2nd. edn. London, SAGE Publications.

- Sère, B. (2007) Penser l’amitié au Moyen Âge: Étude historique des commentaires sur les livres VIII et IX de l’Éthique à Nicomaque (xiiie -xv e siècle). Turnhout, Brepols.

- Sigurðsson, J. V. (1999) Chieftains and Power in the Icelandic Commonwealth. Odense, Odense University Press.

- Southern, R. W. (1963) St Anselm and his Biographer. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Southern, R. W. (1990) Saint Anselm. A Portrait in a Landscape. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- van Eickels, K. (2002) Vom inszenierten Konsens zum systematisierten Konflikt. Die englishfranzösischen Beziehungen und ihre Wahrnemung an der Wende vom Hoch- zum Spätmittelalter. Stuttgart, Jan Thorbecke.

- Wasserman, S. and Faust, K. (1994) Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- White, C. (1992) Christian Friendship in the Fourth Century. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Ysebaert, W. (2001) Ami, client et intermédiaire: Étienne de Tournai et ses réseaux de relations (1167- 1192). Sacris Erudiri, 40, 415-67.

- Ysebaert, W. (2005) Medieval Letter-Collections as a Mirror of Circles of Friendship? The Example of Stephen of Tournai, 1128-1203. Revue Belge de philologie et d’histoire, 83, 285-300.

- Ysebaert, W. (2009) Medieval letters and letter collections as historical sources: methodological questions and reflections and research perspectives (6th-14th centuries). Studi Medievali, ser. 3, 50, 41-73.

Originally published by Amity: The Journal of Friendship Studies 1:1 (2018, 69-88), University of Leeds, republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.