From the Gold rush to the tech boom, people have gone to San Francisco from all directions in search of fortune.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

A Built Environment

Eyewitness Accounts of the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake

Rich and poor, Chinese and white, were suddenly sleeping and eating side by side, to mutual bewilderment.

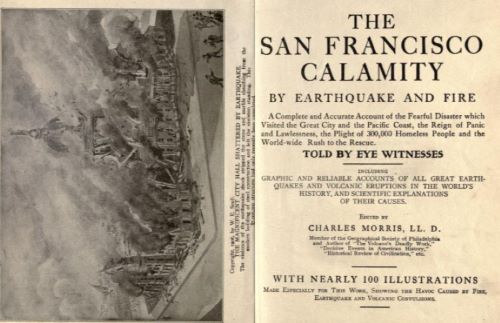

The San Francisco Calamity by Earthquake and Fire (1906) was known in the publishing industry as an “instant disaster book”. This genre coalesced partly because there were so many disasters at the turn of the last century: the 1889 Johnstown Flood; the 1900 Galveston Hurricane; the 1902 eruption of Mount Pelée; the 1903 Iroquois Theatre Fire; the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904; the 1904 burning of the steamboat General Slocum; and finally, the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906, which killed over 3,000 people and destroyed 80% of the city. All of these became topics of books that followed a certain pattern. A journalist was hastily dispatched to the scene, he furiously filed copy, the page count was fattened up with previously published odds and ends, and images were cut in, the more the better. Get the book to market before interest flits away.

The author of The San Francisco Calamity was Charles Morris, though he’s actually credited as editor, an elision that allowed publishers a freer rein on the book’s final components. Morris was a professional writer who published a great number of popular histories, as well as pseudonymous dime store novels. It’s not clear when he arrived in San Francisco from Philadelphia, nor when he finished his manuscript, but his publisher claimed it was a matter of weeks. If the book wasn’t the first account of the earthquake, it was certainly among the first.

The San Francisco Calamity justifies its length with a comparative survey of many other earthquakes, as well as a history of San Francisco, but the heart of the book is a small section that begins about fifty pages in, when Morris directly quotes his stunned interviewees. Their eyewitness accounts are sharp and disjointed, their experience not yet shorn of its surprise. Nothing has been smoothed or strategically forgotten. They describe a pageant of wretchedness, still unfolding.

The billboard advertising beer that was converted into a public message board, and crowded with death notices. Thieves cutting off fingers and biting off earlobes to seize the jewelry of the dead. Shelters made of fine lace curtains and table cloths. Injuries seeping blood, and thousands of people with nothing to wear aside from their pajamas. Some survivors never stopped shrieking and others went comatose. Some refused to be parted with their piano, or their sewing machine, or their canary, or their lover’s body. Garbage wagons toted corpses. The air was thick with the smell of gas and smoke, and dangling electrical wires shot off blue sparks.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE PUBLIC DOMAIN REVIEW

Untimely Futures

In Oakland, California, when it comes to Black homelessness and dispossession, dystopia is already here.

He says calmly, “Look,” gesturing with his languid hand, “Look, I come from one of the oldest cities in the world. The oldest civilization. They build a parking lot and they think that it is a civilization.” Stunned, I burst out laughing. And he joins me. We laugh and laugh and I reply, “True, true.” “The oldest civilization,” he says again. “True,” I repeat.

Dionne Brand, 2001

Imagine, if you will, The Ark, a degraded cruise ship propped on blocks and languishing in an empty parking lot in West Oakland, California, against the backdrop of the I-880 freeway. In the shadow of the ship, the weedy lot is populated by a “tent city” or homeless encampment, an agglomeration of Teslas, tents, and campers. (Yes, Teslas.) Charcoal grills, glass-encased seating pods, and charging stations huddle in the ship’s lee. Wires strung with cheerful pennants stretch down from reactors attached to the ship’s hull to vehicular generators primed for the electric cars scattered throughout the camp. Above, on the sundeck, you can see more generators and a further colorful assortment of tarp-covered tents and patio umbrellas, all framed by strands of pennants. The ship’s hull, like the façade of the adjoining Beaux-Arts train station — built in 1912 as one of three transportation hubs then serving the East Bay, and decommissioned in 1989 — is adorned with graffiti. One of the more prominent tags proclaims in red the anti-capitalist Rousseauian phrase EAT THE RICH, with an accompanying sickle-and-fork emblem.

The Ark (2020) is a photomontage by the artist Olalekan Jeyifous, part of the series “The Apocryphal Gospel of Oakland,” which visually constructs the improbable ongoing story of Oakland’s unhousing crisis through speculative digital collages. The scene depicted in The Ark seems improbable, an allegorical fantasy. Recall, however, that in December 2019, several months before COVID-19 took hold, Oakland’s then-city council president Rebecca Kaplan introduced a plan to dock a decommissioned cruise ship at the Port of Oakland, adjacent to the West Oakland neighborhood. The idea was to provide emergency shelter for nearly 1,000 unhoused individuals.

Oakland’s Port remains one of the busiest in the nation, engineered with a federally regulated infrastructure designed explicitly for cargo ships, making it structurally untenable for docking cruise liners. Even so, Kaplan and her colleagues argued that a “floating hotel” could temporarily address the 86 percent spike in homelessness that Oakland had witnessed between 2015 and 2019. Kaplan noted that cruise ships had been used as emergency housing in the aftermath of natural disasters, for instance following Hurricane Katrina. Homelessness, of course, is an unnatural disaster. But Kaplan’s plan was just one in a long line of attempts to ameliorate the crisis; Oakland and other Bay Area cities have been experimenting since 2015 with other “emergency” proposals, including legalizing tent encampments in specific parking lots and on certain vacant lots.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT PLACES JOURNAL

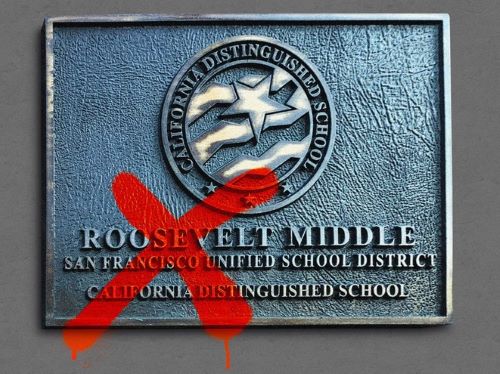

Demolishing the California Dream: How San Francisco Planned Its Own Housing Crisis

Today’s housing crisis in San Francisco originates from zoning laws that segregated racial groups and income levels.

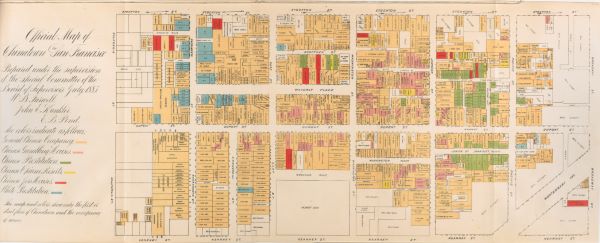

If you want to understand San Francisco’s self-inflicted housing crisis, look no further than the city’s very first zoning law, commonly known as the Cubic Air Ordinance, which set a disturbing standard for the city’s eventual missteps. Proposed in 1870, during a time of rampant real-estate speculation in a boomtown renowned for its lawlessness, the new law required boarding houses to offer a minimum amount of space per tenant. Officials claimed this would promote safer housing and improve residents’ quality of life, a noble cause for government intervention.

But the law’s true purpose—to criminalize Chinese renters and landlords so their jobs and living space could be reclaimed for San Francisco’s white residents—set an ominous precedent. With the Cubic Air Ordinance, city leaders laid the groundwork for 150 years of exclusionary zoning or land-use policy designed to protect the status quo, rather than responsibly manage growth. Often fueled by racism and greed, the dark history of San Francisco urban planning is a story that’s still being told, its latest chapter being the city’s current housing crisis.

For visitors and locals alike, part of San Francisco’s allure is its seeming incongruity: Victorian houses perch on hills near glass skyscrapers, antique cable cars clank up the same streets where new technologies debut. Few realize how profoundly the city’s physical form has been shaped by its planning department, whose best intentions have been overshadowed by efforts to appease the city’s wealthy, well-connected homeowners.

“It is no accident that land is called real estate,” Kenneth T. Jackson wrote in his influential 1985 book Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanziation of the United States. “For many centuries, ownership of land has been not just the main but often the only basis of power.” This power was on full display earlier this year, during the debate over California Senate Bill 827, which would have “upzoned” or raised height limits near frequent transit stops. Many neighborhood groups, city councils, and politicians decried the loss of “local control”— “local” being a positive, vaguely artisanal-sounding buzzword used by city progressives who derided the bill as a “one-size-fits-all” solution that would hurt low-income residents.

However, American cities have consistently asserted so-called “local control” to increase inequality, establishing exclusionary zoning laws to prevent the construction of denser multifamily housing, redevelop low-income neighborhoods, and push poorer residents from their communities. In San Francisco, residents have exploited “local control” to make development as difficult as possible by lowering building-height limits, expanding zoning regulation, and increasing the veto power of homeowners. These privileged neighbors have often appropriated low-income residents’ fears of gentrification and eviction to block any new housing, despite the fact that studies have repeatedly shown that in markets with high demand, adding housing of any kind typically helps decrease displacement.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT COLLECTORS WEEKLY

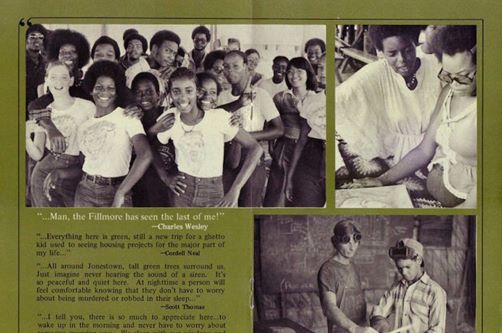

Imagining a Past Future: Photographs from the Oakland Redevelopment Agency

City planner John B. Williams — and the photographic archive he commissioned — give us the opportunity to complicate received stories of failed urban renewal.

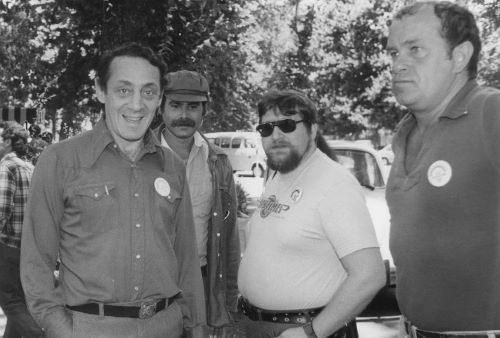

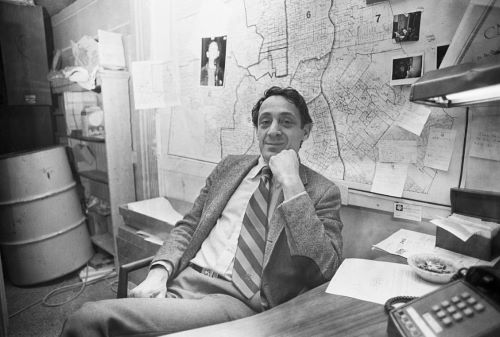

On any given workday in downtown Oakland, thousands of commuters enter and exit the 12th Street City Center station of the Bay Area Rapid Transit, or BART, rushing past a large bronze bust of John B. Williams. The statue, like many memorials, fails to meet its mission: to remind Oakland’s residents who John B. Williams was and what role he played in the city that named its downtown plaza and part of its intercity highway for him. The charismatic director of the Oakland Redevelopment Agency from 1964 to 1976, Williams was once called the most “powerful and effective Black man in city government.” Lionel Wilson, Oakland’s first Black mayor, has noted that before his own election in 1977, Williams had been considered a potential mayoral candidate. He is now difficult to locate in the public record and in the public imagination. But like the bust at City Center Plaza, his legacies hide in plain sight. Williams’s story is central to the history not only of this particular place but also of many communities upended by the urban renewal programs of the mid-20th century.

In 1949, the federal government passed the Housing Act, making funds for urban renewal projects available to many American city governments. Oakland undertook a program of aggressive redevelopment, redlining vulnerable working-class communities to make way for new infrastructure and industry. The city’s African-American community, which had tripled in population in the decades before and after World War II, was disproportionately affected. Racialized housing restrictions confined the majority of this growing community to overcrowded West Oakland — just west of downtown — where the housing stock was increasingly becoming derelict.

A postwar housing crisis brought on by the influx of migrants and loss of wartime jobs resulted in deeply segregated residential neighborhoods across the East Bay. Traditionally multi-ethnic communities (including Mexican, Asian, Portuguese, and Irish families) were transformed as white Oaklanders took advantage of federal loan and mortgage programs — subsidized by the Federal Housing Administration and the Veteran’s Administration — to purchase new homes in the suburbs. Meanwhile, due to discriminatory lending practices, racist zoning laws that restricted African Americans to neighborhoods west of Oakland’s Adeline Street, and low owner-occupancy rates, homes in and around downtown fell into disrepair. This devaluation of property — specifically in West Oakland — coupled with the decline of the city’s commercial district, created anxiety for local officials, who felt especially threatened by the commercial pull of San Francisco following the completion of the Bay Bridge in 1936. In 1959, a sweeping redevelopment plan for West Oakland was unanimously approved by the city council.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT PLACES JOURNAL

As Evictions Loom, Cities Revisit a Housing Solution From the 70s

Proposals giving tenants the right to purchase their building were revived when Covid-19 put renters at risk.

Even before the pandemic rang down the curtain on much of the U.S. economy, times could be tough for the roughly 110 million Americans living in rental housing. For many of them, paying the landlord was a tattered hope and staving off the sheriff’s deputies an endless worry. Nearly 4 million eviction petitions were filed each year. On any given night as many as 200,000 people were without a home.

In the pandemic, losing shelter is an ever-present threat on a far bigger scale, by some estimates potentially affecting upward of 30 million cash-strapped tenants. A calamity of that magnitude has been averted, for now, under a moratorium on evictions imposed through 2020 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But equitable and compassionate solutions to America’s chronic housing problems will clearly remain an elusive goal long after the coronavirus is conquered.

One method with promise is explored in this video from Retro Report, whose mission is to examine major events of the past for their continuing impact and enduring lessons. The underlying premise is a familiar one: giving people a genuine stake in their apartments and houses by turning renters into owners. The video focuses on two situations separated by half a century: in San Francisco, where the idea was not able to get off the ground, and in Minneapolis, where it has taken flight, albeit with an uncertain future.

The San Francisco story dates to the late 1960s on Kearny Street, in a neighborhood known as Manilatown because of its many immigrants from the Philippines. There, the three-story International Hotel was home to 150 people, principally Filipino laborers who rented rooms for about $50 a month, about $380 in today’s dollars. In 1968 the hotel’s owners handed tenants eviction notices. Developers had begun to reconfigure the city in the name of urban renewal. The I-Hotel, as many called it, was to be razed to make way for a parking lot.

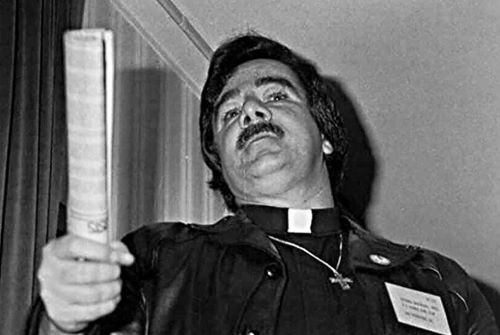

The tenants resisted. They were supported by neighbors, church leaders and community activists like Emil A. De Guzman Jr., then a college student who had lived in the hotel for a while. “The whole struggle came down to just one thing,” he told Retro Report recently. “It became people’s rights over property rights.”

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT RETRO REPORT

Privatizing the Public City

Oakland’s lopsided boom.

In a recent article in Harper’s Magazine, Kevin Baker looks at a familiar story, the disconcerting transformation of a coastal American city into an enclave built by and for the wealthy. At issue is not simply “the astounding rise in housing prices, disruptive as that is. It is also the wholesale destruction of the public city.” The public city, as he describes it, should be made up of more than residential mega-developments and office towers. It should encompass investment in parks and libraries, subway lines and recreation centers, amenities for all socioeconomic classes. Baker is writing about New York. But he could as easily be discussing the San Francisco Bay Area — certainly San Francisco and, more recently, Oakland, the city where I live and whose urban planning and development I have studied for many years.

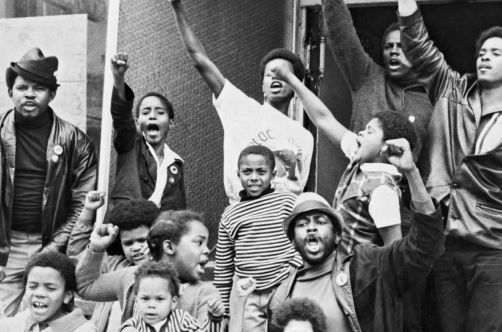

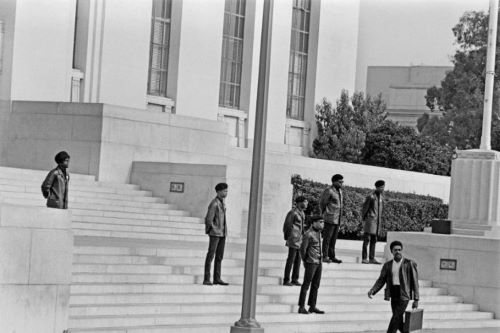

It’s not only my own experience that makes Oakland apt as a case study of the public city in jeopardy. In this era of what Baker calls “the urban crisis of affluence,” we need to acknowledge the particular importance of mid-sized cities in the orbit of larger ones, moving past the relentless focus on global megalopolises and attending to the second-tier municipalities where most working people live. Oakland has long been the poor relation across the bay from San Francisco, making it particularly vulnerable to overspill from gentrifying San Francisco, much as it was earlier neglected in the postwar suburban migration. It is, moreover, a fascinating place in its own right, the home of Jack London, Julia Morgan, Gertrude Stein, and Earl Warren, the Black Panthers and Ishmael Reed; where recent mayors have included Jerry Brown (1997-2007) — four-time governor of California. Spared the devastation of the 1906 earthquake, Oakland boasts the Bay Area’s greatest array of building types — from warehouses to office high rises to movie theaters to single-family homes — and vintages — including Victorian, Beaux Arts, Art Deco, and modernist exemplars. In a few years, its densely built, mixed-use downtown may be one of the most active and pleasant in the western United States.

In earlier boom cycles here, market-driven development was accompanied by public investment. Oakland in the 1910s saw the construction of civic buildings like City Hall (1914) and the Municipal Auditorium (1915), spearheaded by Mayor Frank Mott. In the Depression years, a local bond issue augmented by support from the federal Public Works Administration funded the rebuilding of the Alameda County Superior Courthouse (1936), complete with murals and sculpture by Works Progress Administration artists. In the 1950s and ’60s, the Bay Area Rapid Transit District brought together counties on both sides of the bay to plan and build the Bay Area Rapid Transit System, or BART.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT PLACES JOURNAL

Can Reparations Bring Black Residents Back to San Francisco?

San Francisco has proposed the nation’s most ambitious reparations plan, including $5 million cash payments and housing aid that aims to bring people back.

Standing at the stoop of her childhood home — a slim but stately Victorian shaded by an evergreen pear tree — Lynette Mackey pulled up a photo of a family gathering from nearly 50 years ago. The men were all in suits, the women in skirts. Ms. Mackey, a teenager in red bell bottoms, stretched her arms wide and had a beaming smile.

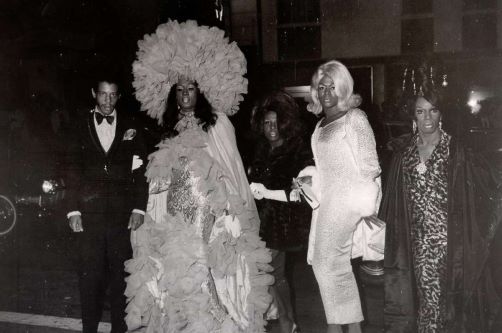

Soon after that time, in the 1960s and 1970s, Ms. Mackey watched the slow erasure of Black culture from the Fillmore District, once celebrated as “the Harlem of the West.” The jazz clubs that drew the likes of Billie Holiday and Duke Ellington disappeared, and so, too, did the soul food restaurants.

By the mid-1970s, many of her friends were gone as well, pushed out by city officials who seized homes in the name of what they called “urban renewal.” Then, finally, her family lost the house they had purchased in the 1940s after migrating from Texas. In many cases, the old Victorian homes were torn down and replaced with housing projects, but the city kept Ms. Mackey’s home standing, and it has since been renovated into government-subsidized apartments.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE NEW YORK TIMES

Redlining and Gentrification

Exploring the deep connections between redlining, gentrification, and exclusion in San Francisco.

How is a policy that began in the 1930s still felt in American cities? Check out our new video on the long and damaging history of redlining, and its connection to gentrification today.

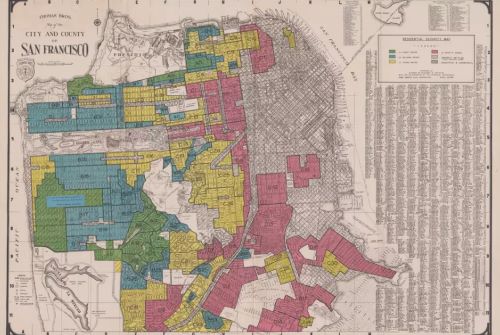

Redlining was a process in which the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), a federal agency, gave neighborhoods ratings to guide investment. This policy is so named for the red or “hazardous” neighborhoods that were deemed riskiest. These neighborhoods were predominantly home to communities of color, and this is no accident; the “hazardous” rating was in large part based on racial demographics. In other words, redlining was an explicitly discriminatory policy. Redlining made it hard for residents to get loans for homeownership or maintenance, and led to cycles of disinvestment.

This history is not behind us: 87% of San Francisco’s redlined neighborhoods are low-income neighborhoods undergoing gentrification today.

Watch the video to see this connection for yourself, and learn more about the lasting impacts of this discriminatory policy. The past is embedded in the present-day experience of our neighborhoods and cities; it is important to the future of cities that we confront this history.

While this video explores the overlap between redlining, gentrification, and exclusion in San Francisco, these trends are common across the Bay Area. Stay tuned for videos on other Bay Area cities coming soon.

Learn more about redlining, in your community and beyond:

Want to know how your neighborhood was rated by HOLC? Check out the University of Richmond’s “Mapping Inequality” Project for interactive redlining maps.

Want to understand the connection between redlining maps and other data in your community?

- The dataset from University of Richmond’s digitized maps is now on PolicyMap so that users can overlay this polygon data with a number of other layers to explore trends in residential and economic segregation, along with a host of other areas.

- Recent research from NCRC, “HOLC ‘Redlining’ Maps: The persistent structure of segregation and economic inequality,” looks at persistent impacts of redlining in cities across the US — on economic and racial segregation, inequality, and gentrification, as well as exploring regional differences.

NPR’s recent explainer video, “Why Are Cities Still So Segregated?” teases out the connections between redlining and the landscapes of opportunity in our cities — in schools, health, wealth, policing, and more.

SEE MORE AT THE URBAN DISPLACEMENT PROJECT

A Trip Down Market Street before the Fire

This film is a rare record of San Francisco’s downtown area before its destruction in the 1906 earthquake and fire.

This film, shot from the front window of a moving Market Street cable car, is a rare record of San Francisco’s principal thoroughfare and downtown area before their destruction in the 1906 earthquake and fire. The filmed ride covers 1.55 miles at an average speed of nearly 10 miles per hour. Market Street, graded through sand dunes in the 1850’s, is 120 feet wide, and nearly 3.5 miles long. The street runs northeast from the foot of Twin Peaks to the Ferry Building. According to an April 30, 2010 article in the San Francisco chronicle and in a 60 minutes television segment broadcast on October 17, 2010, silent film historian David Kiehn determined from the depiction in the film of the puddles in the cavities by the rails on the street–and especially autos driving through puddles splashing water–that the film could not have been shot in September 1905 as that month was “bone dry.”

After searching weather reports in a number of San Francisco newspapers, Kiehn learned that no heavy rain was reported until late March and into early April of 1906. Further research uncovered an April 28, 1906 advertisement for the film in the theatrical magazine, the New York Clipper, suggesting that the film was shot on or around April 12, 1906 due to the long lead time for print ads for magazines of the day and the amount of time required to ship the film to New York by train. Kiehn also confirmed that one of cars in the film with license plate number 4867 had been registered in early 1906. An interesting feature of the film is the apparent abundance of automobiles. However, a careful tracking of automobile traffic shows that almost all of the autos seen circle around the camera/cable car many times (one ten times). This traffic was apparently staged by the producer to give Market Street the appearance of a prosperous modern boulevard with many automobiles. In fact, in 1905 the automobile was still something of a novelty in San Francisco, with horse-drawn buggies, carts, vans, and wagons being the common private and business vehicles.

“Produced as part of the popular Hale’s Tours of the World film series, the film begins at the location of the Miles Brothers film studio, 1139 Market Street, between 8th and 9th Streets; it was filmed 14 April 1906, four days before the devastating earthquake and fire of 18 April 1906, which …

SEE MORE AT THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Found Footage Offers a New Glimpse at 1906 San Francisco Earthquake

Nine minutes of newly found footage shows the aftermath of the earthquake that devastated San Francisco in 1906.

On Saturday night, a small crowd filled a 120-seat theater in Fremont, Calif., to watch a movie unlike any other on the big screen, one that offers a fresh look at a tragic chapter in American history.

The nine-minute silent film, much of it previously thought to be lost, shows the ruins left by the earthquake that ravaged San Francisco 112 years ago, according to David Kiehn, a film historian who helped to identify and restore the footage, which he said was originally shot by the pioneering Miles Brothers film studio in San Francisco.

The rediscovered work is a fitting follow-up to the famous Miles Brothers production “A trip down Market Street before the fire,” which shows the bustling city just days before the earthquake, its inhabitants unaware of the disaster to come on April 18, 1906.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE NEW YORK TIMES

Roads to Nowhere: How Infrastructure Built on American Inequality

From highways carved through thriving ‘ghettoes’ to walls segregating areas by race, city development has a divisive history.

It’s a little after 3pm in Detroit’s 8 Mile neighbourhood, and the cicadas are buzzing loudly in the trees. Children weave down the pavements on bicycles, while a pickup basketball game gets under way in a nearby park. The sky is a deep blue with only a hint of an approaching thunderstorm – in other words, a muggy, typical summer Sunday in Michigan’s largest city.

“8 Mile”, as the locals call it, is far from the much-touted economic “renaissance” taking place in Detroit’s centre. Tax delinquency and debt are still major issues, as they are in most places in the city. Crime and blight exist side by side with carefully trimmed hedgerows and mowed lawns, a patchwork that changes from block to block. In many ways it resembles every other blighted neighbourhood in the city – but with one significant difference. Hidden behind the oak-lined streets is an insidious piece of history that most Detroiters, let alone Americans, don’t even know exists: a half mile-long, 5ft tall concrete barrier that locals simply call “the wall”.

“Growing up, we didn’t know what that wall was for,” says Teresa Moon, president of the 8 Mile Community Organization. “It used to be a rite of passage to walk on top of the wall, like a balancing beam. You know, just kids having fun, that kind of thing. It was only later when I found out what it was for, and when I realised the audacity that they had to build it.”

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE GUARDIAN

Mobility and Mutability: Lessons from Two Infrastructural Icons

The Embarcadero Freeway and the Berlin Wall exemplified how the politics of mobility reflected the arrangements of power in each society.

An imposing monument to ideology and power, it stood as a marker of urban division from its construction during the height of the Cold War until its fate was sealed in 1989. Featured in films from noir to arthouse, its austere aesthetics absorbed observers on the scene and around the world. With its grey, alienating appearance, it also attracted no shortage of denunciators. “Oppressive,” one urban design expert opined in retrospect, “does not begin to describe it.” It’s still remembered by history, even if most people now enjoy inhabiting or traversing the public space its absence affords with little thought to this once formidable fabrication.

I refer, of course, to San Francisco’s Embarcadero Freeway.

But this reference also recalls that structure’s infrastructural doppelgänger; Berlin’s infamous edifice was also built to control mobility and to shore up a system of unequally distributed power.

Standing as they did across the same temporal span, the Freeway and the Wall, despite their differences, invite comparison for the lessons they hold. Two of those lessons – that mobility is power, and that nothing lasts forever – might issue from the twentieth century, but they are particularly salient for thinking about the city of the twenty-first.

In Berlin back in the early Cold War days of Conrad Adenauer and Walter Ulbricht, the East German state faced the problem of an unmanageably mobile citizenry. Farmers, artists, academics, and doctors were prominent among those departing across the open border. Between the fall of the Nazis and the rise of the Wall, three and a half million people fled the German Democratic Republic. 1 in 6, in other words, went west.

From 1961 to 1989, the GDR’s solution brought a brutal stability to the situation, with comings and goings strictly controlled. The greatest symbol of the Cold War caught the attention of the world. And as was true of the Embarcadero Freeway, the Berlin Wall also drew the eye of the camera., perhaps most memorably in the moody reverie of Wings of Desire (1987). Though difficult to see at the time, when the angels of that film looked upon the Wall, their faces were turned toward a past that would be radically altered by the political storms of the near future.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT IMPERIAL & GLOBAL FORUM

The Abandoned Houses of Instagram

People lived in these places once. What mysteries did they leave behind?

Vines crept up the house. It looked like it was about to cave in. The Colonial in Roscoe, N.Y., a hamlet of the Catskills, was decrepit — which made it all the more appealing to Bryan Sansivero, 36, and a friend, who had arrived before dawn. They entered the musty, empty dwelling, which was not really a dwelling because no one dwells there, and sat in the dark for about half an hour until sunrise.

Soon, the living room was aglow and its contents revealed: antique furnishings, a fireplace with a knickknack-lined mantel, and, most shockingly, a tiger skin rug (the creature’s mouth agape) and a hunting rifle. “We were like, this house is insane. How is this just sitting here and completely abandoned like this?” Mr. Sansivero said.

Despite the dilapidated condition, including peeling walls and an unpleasant kitchen, the house was in pretty good shape. He snapped photos and later shared them in a Facebook group dedicated to old houses, where his posts stir emotions ranging from nostalgia to sadness to skepticism that the house was actually found in that condition (Mr. Sansivero said that the houses’ belongings have typically been staged by previous visitors but that he only makes minor adjustments).

Mr. Sansivero is a professional portrait photographer by trade, but taking pictures of abandoned houses has been a passion of his since college, when he majored in filmmaking and shot a documentary short film about an abandoned hospital on Long Island. His eyes were opened to the mysterious world of such properties.

His attention shifted to houses when he visited family in Pennsylvania and took stock of how many abandoned ones there were in the rural areas. “I became fascinated,” Mr. Sansivero said. “Just going to time-capsule homes where it’s like the family just disappeared.”

He’s been to hundreds of abandoned houses, but only a few make it onto his Instagram feed. “It has to have a moody kind of light,” Mr. Sansivero said. “It has to be colorful, which I think draws in the viewer. It’s eye-catching.” And, he said, “I tend to really like unusual items that are left behind.”

Online, people are attracted to a broad range of abandoned houses. Sometimes it’s a country house standing forlornly in a field, or a mansion in Ontario where the focal point is the architectural details, or a house in Nantes, France with an Old World vibe. In the Facebook group “I Love Old Houses and Gardens,” posts dedicated to abandoned houses can draw thousands of reactions. People have long loved creepy things and even sad things, and these houses hit those notes and more.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE NEW YORK TIMES

Economy and Labor

How Could ‘The Most Successful Place on Earth’ Get So Much Wrong?

A new book conjures the complexity of the Bay Area and the perils of its immense, uneven wealth.

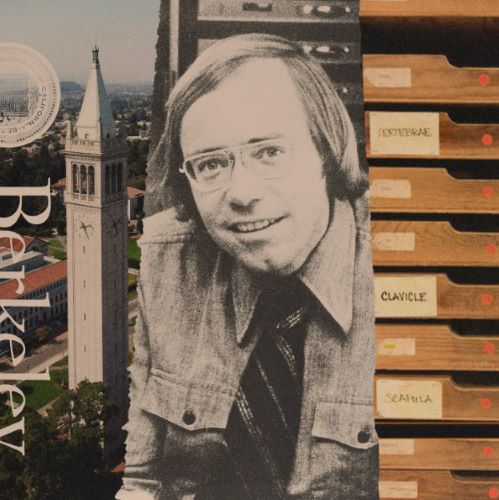

Pictures of a Gone City is the culmination of the life’s work of Richard A. Walker, a professor emeritus of geography at the University of California, Berkeley. A student of the great Marxist geographer David Harvey, Walker brings a profoundly historical approach to his scholarship. His lens spans economics, urban design, politics, and the environment, to name just a few of his interests.

Walker’s new book is urban geography for our times. It illuminates the basic crisis and contradiction of the San Francisco Bay Area, which is an example of capitalism at its most innovative and dynamic, and simultaneously the site of severe inequality and failing public policies and infrastructure. Walker has lived and worked in the Bay Area for most of his life. I was delighted to speak with him about topics ranging from the real geographic definition of the Bay Area, to its history of innovation (stretching back to the Gold Rush days), to the contemporary movements that might help the Bay Area reclaim its radical roots.

In the 1950s postwar era, when the Beats were going strong, and right through the 1960s, San Francisco was remarkably cheap, actually, because it wasn’t as in demand as New York. So people could find places to rent in North Beach, which now is regarded as very luxurious. What [happened] is, around 1970, there’s an inflection point where prices in California in general take off and start to outrun most of the rest the country. And then there’s another inflection point around the 1990s.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT BLOOMBERG CITYLAB

Docking Stations

A conversation with historian Peter Cole about his recent book, Dockworker Power.

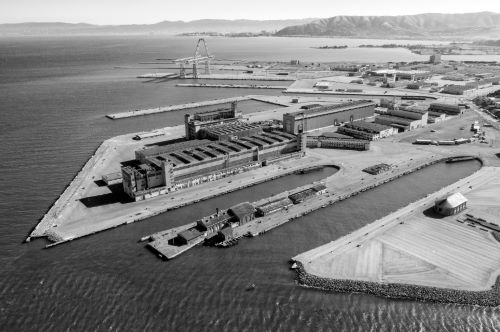

For hundreds of years, and through today, overseas shipping has been the primary method of global trade. During most of that time, the loading and unloading of cargo involved hundreds of workers manually hauling crates — that is, until containerization revolutionized the industry. Beginning in the 1960s, shipping companies adopted standardized containers, which could seamlessly be lifted from trucks onto ships with enormous cranes and unloaded the same way. Suddenly, the number of workers necessary for a dock’s efficient operation dropped exponentially.

Historian Peter Cole’s recent book, Dockworker Power, tells the story of how two different groups of workers — the International Longshore and Warehouse Union’s Local 10 in the San Francisco Bay Area, and formally unorganized, but radically minded dockworkers in Durban, South Africa — dealt with the automation of their industry. Being formally organized and relatively powerful, ILWU’s Local 10 was able to negotiate what amounted to substantial retirement packages for its redundant members; being unorganized and clenched in the fist of apartheid, Durban dockworkers were not able to win such concessions.

These histories provide two paths for workers everywhere who are threatened by automation — the organized winning compromises, the unorganized swept aside — but the most interesting route is the road not taken. Even after Local 10’s supposedly successful negotiations, some union members questioned if further radical conflict, rather than compromise, would not have served them better by preserving their power, rather than selling it.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE SMART SET

Martin Luther King Jr., Union Man

Most people think of Martin Luther King Jr. as a civil rights leader. What many don’t know is that he also championed labor unionism.

If Martin Luther King Jr. still lived, he’d probably tell people to join unions.

King understood racial equality was inextricably linked to economics. He asked, “What good does it do to be able to eat at a lunch counter if you can’t buy a hamburger?”

Those disadvantages have persisted. Today, for instance, the wealth of the average white family is more than 20 times that of a black one.

King’s solution was unionism.

In 1961, King spoke before the AFL-CIO, the nation’s largest and most powerful labor organization, to explain why he felt unions were essential to civil rights progress.

“Negroes are almost entirely a working people,” he said. “Our needs are identical with labor’s needs – decent wages, fair working conditions, livable housing, old age security, health and welfare measures, conditions in which families can grow, have education for their children and respect in the community.”

My new book, “Dockworker Power: Race and Activism in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area,” chronicles King’s relationship with a labor union that was, perhaps, the most racially progressive in the country. That was Local 10 of the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union, or ILWU.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE CONVERSATION

A Brief History of the Gig

The gig economy wasn’t built in a day.

In early 2012, San Francisco taxi drivers began to raise the alarm at organizing meetings and city hearings about “bandit tech cabs” pilfering their fares. “I’ll sit at a hotel line, and I see one of these guys in their own car come up, hailed by some guy’s app, and they’ll turn down my fare,” Dave, who had been driving a taxi for fourteen years, said at a meeting that April. “They steal it. It’s insulting.” Other cabbies said they were seeing the same thing, and that their income was suffering as a result. “I think I made 20 percent less last week than normal,” one driver lamented. He wanted city officials to know; surely, they would put an end to it.

These taxi workers were experiencing the very earliest stage of a global re-organization of private and public transportation, fueled by billions of dollars of financing from venture capitalists. Under the shadow of the Great Recession, in a period of high unemployment and slow job growth, Uber, Lyft, and their erstwhile competitor Sidecar used this technocapital to begin offering almost anyone with access to a car a way to make money by driving people around San Francisco. The companies aggressively marketed themselves as disruptors of the transportation industry; consumers and commentators, seduced by on-demand, technology-fueled mobility and the prosocial promise of what the companies called “collaborative consumption,” enthusiastically adopted their narrative.

Cabbies, however, saw Uber and Lyft as well-financed corporate continuations of the taxi companies that had long subjugated them. “This isn’t about technology,” Mark, a long-time taxi worker and advocate told me in 2013. He explained that, for the previous few years, San Francisco taxi drivers had already been using an app called Cabulous, which essentially did what Uber and Lyft were doing. “They claim they’re innovative and new, but we already have this technology,” he went on. What was different, Mark described, was that Uber and Lyft had “a new exploitative business model,” though it was just “one step removed from the leasing model that the taxi companies have been using for years.”

Since 2012, much of the positive discourse around Uber and Lyft has continued to regurgitate the notion that these are companies built on technological innovations that brought new forms of transportation to people and places who needed them. Meanwhile, critiques of these companies, and of the gig economy as a whole, have typically seen Uber and Lyft as breaking sharply from earlier modes of employment to create new forms of precarity for workers. In both cases, the public discussion tends to see these companies as creating major discontinuities, whether of technology or of labor models. What Mark pointed out, however, is that Uber and Lyft are in many ways not as different as we tend to think from the taxi companies that prevailed until 2012.

In 2020, almost a decade after the advent of Uber and Lyft, we seem to be at another turning point. The ride-hailing industry is facing a wave of militant self-organizing and claims to employment status by drivers. So far, the most significant mobilization has been the fight over AB5, a California assembly bill that was signed into law in September 2019, and which makes it much clearer that drivers should be treated as employees of Uber and Lyft. The companies have fought this reclassification in myriad ways, and some drivers fear that it may cause them to lose their flexibility. But those who have welcomed the passage of AB5 hope it will deliver them many of the benefits—from healthcare to a guaranteed minimum wage—that Uber and Lyft have so far denied them. On all sides of the issue, no one doubts that we are at a critical juncture in the history of labor and urban transportation.

But in order to sort through the arguments surrounding AB5 and grasp the significance of this moment, we must do something that the discourse around ride-hailing has failed to do: situate ourselves historically, tracing both the continuities and the discontinuities that the cabbie Mark pointed to. Our present moment is largely the product of two neoliberal shifts in the taxicab industry—and, in a certain sense, in US society as a whole—that occurred in the late 1970s and the 2010s. Understanding the reasons for these shifts can help us get beyond the easy assumptions made on different sides of the debate: that employee status is an unalloyed good or ill, that innovation made the rise of Uber and Lyft inevitable, or that the issues raised by the sector are matters of technology rather than politics.

Few people understand those reasons better than the drivers themselves—though, like other workers, they rarely have their voices centered in public discourse. By listening to drivers’ accounts of how their industry operates and has changed, we can come to understand how and why, despite some fears and ambivalence, they are using employee status to create a much-needed friction in the wheels of technocapital.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT LOGIC(S)

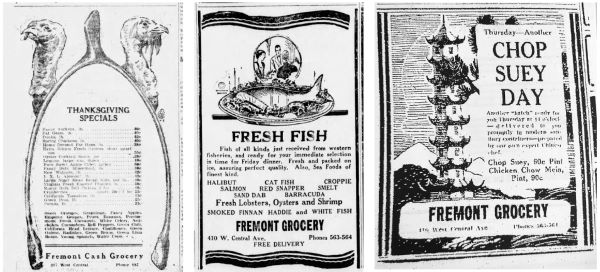

How a War Over Eggs Marked the Early History of San Francisco

Competition over eggs on the Farallon Islands in the midst of the California Gold Rush in San Francisco led to an all out war between eggers.

Egg dishes are a flavor of home. We want them the way our fathers or mothers or grandparents made them. An egg conjures memories of learning to cook for many of us, since making eggs is perfect for teaching a kid. Even if one disdains a straight scramble, the egg is a key ingredient in many comfort foods, including pancakes and birthday cake.

For all these reasons, eggs carry a certain nostalgia. They remind us of paradise lost—the childhood that is done, the beloved elder chef who is buried, the metabolism that once tolerated syrupy breakfast carbs. And nostalgia has power. Would you kill to return to a yolk-kissed moment when a caregiver served up love on a plate? Some men would. And, indirectly at least, some men did during the Egg War of the Farallon Islands.

The Egg War began unofficially in 1848 with the Gold Rush. San Francisco started the year with a mere thousand souls, but over the next twelve months the population rose to twenty-five thousand. The city experienced scarcities of women and of food, particularly protein. Scaling up farms to provide for the local population proved harder than it seemed. Nobody could get large groups of chickens to survive there, and the technical solutions to this problem were decades off. Without chickens, of course, there could be no eggs. And without eggs, there could be no cakes, morning scrambles, pancakes, puddings, or muffins. As Napoleon once put it, “An army marches on its stomach,” and a rootin’-tootin’ army of miners in the Wild West doubly so.

As gold poured into the city, the prices for fresh eggs skyrocketed. Out in the field, a single chicken egg might sell for $3, while in the city that same egg fetched the still exorbitant price of $1. Even without accounting for inflation, $12 to $36 per dozen eggs is ridiculously expensive. If we account for inflation, the miners paid something astounding—more like $427 to $1,282 per dozen. This explains the origins of Hangtown Fry rather well. According to legend, a guy who had struck gold wandered into the El Dorado Hotel in the mining supply camp of Hangtown (so nicknamed for its penchant for stringing up criminals). He threw down a bag of gold and demanded the most expensive meal the chef could make—which turned out to be oysters and eggs. If someone could bring good fresh eggs to San Francisco Bay, he would more than make his fortune.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT LITERARY HUB

What California Cuisine’s Past Tells Us About Its Future

Into the 1980s, the heart of the California food revolution was also a hub of French fine dining. Why did the goat cheese and sundried tomatoes win?

California, if you’re going to spend over $100 for two on a night out — maybe more like $200 these days — the experience must meet certain expectations. The produce should be fresh and seasonal, sourced from your city’s flagship farmers market. The flavors of a dish should come from light sauces, unexpected herbs or chiles, the smoke of a grill, and most importantly, the key ingredients themselves. The presentation should be unfussy and stylish, matching the rumpled linens, rare sneakers, and vintage jeans you and everyone else in the restaurant are wearing for the occasion.

It feels wrong to call this cooking all the same type of cuisine. The restaurants that practice it could call themselves Italian, French, Mediterranean, Turkish, Mexican, Vietnamese, or American. But there’s a term that encompasses this approach, even if it’s old-fashioned and outmoded, weighed down by goat cheese and sundried tomatoes and Napa cabs: California cuisine.

Pioneered by Alice Waters and her collaborators, notably Jeremiah Tower, at Chez Panisse in the 1970s, this style of cooking emphasized first and foremost respecting the beautiful ingredients produced by farmers in the Golden State. Today, cooking with local ingredients doesn’t sound particularly innovative, let alone era-defining, but that’s merely a sign of this philosophy’s success.

In fact, it’s difficult to understand how specific this style of cooking is, and how this approach transformed dining out in California and the rest of the country, without looking into the past. The show Great Chefs, which ran on PBS and the Discovery Channel in the ’80s and ’90s, is a surprising find of culinary archaeology. For the uninitiated, every episode of Great Chefs is simply constructed, almost refreshingly so. Each 30-minute segment consists of chefs cooking their own recipes, in their own kitchens, over the course of what appears to be a single shoot. There’s little biographical storytelling, minimal drama, and not a single close-up of tweezers. What the camera captures first and foremost is process. It’s closer to YouTube than Chef’s Table.

The second season of Great Chefs, which aired in 1983, focused on San Francisco, an era and region that calls to mind rustic grilled pizzas, little mesclun salads dotted with goat cheese, and fruits on plates. Instead, the season is a paean to pate. Of the 13 episodes, seven feature chefs who are French or trained in traditional French kitchens. They don’t all cook true haute cuisine, but their food is much closer to the refined, rich, technique-heavy cooking of traditional French restaurant kitchens than the rustic peasant-style French cooking that inspired Waters and others. The chefs featured in these episodes make salmon mousseline and duck liver mousse; they craft marzipan roses and bread baskets made of literal bread; they wield multiple wine-reduced sauces and stuff chicken legs with veal. There is so much straining. None of the food could be described as simple.

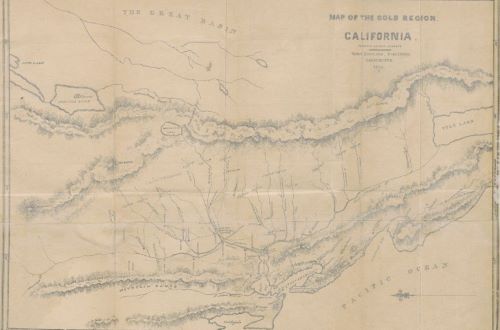

New Map Reveals Ships Buried below San Francisco

Dozens of vessels that brought gold-crazed prospectors to the city in the 19th century still lie beneath the streets.

Every day thousands of passengers on underground streetcars in San Francisco pass through the hull of a 19th-century ship without knowing it. Likewise, thousands of pedestrians walk unawares over dozens of old ships buried beneath the streets of the city’s financial district. The vessels brought eager prospectors to San Francisco during the California Gold Rush, only to be mostly abandoned and later covered up by landfill as the city grew like crazy in the late 1800s.

Now, the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park has created a new map of these buried ships, adding several fascinating discoveries made by archaeologists since the first buried-ships map was issued, in 1963.

It’s hard to imagine now, but the area at the foot of Market Street, on the city’s eastern flank, was once a shallow body of water called Yerba Buena Cove, says Richard Everett, the park’s curator of exhibits. The shoreline extended inland to where the iconic Transamerica Pyramid now rises skyward.

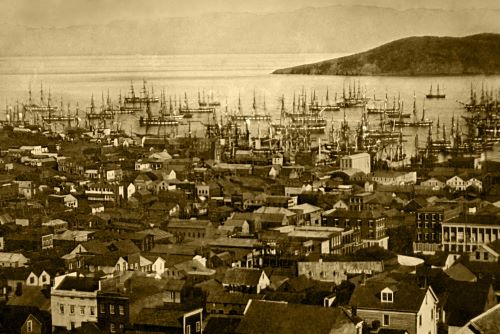

In 1848, when news of the Gold Rush began spreading, people were so desperate to get to California that all sorts of dubious vessels were pressed into service, Everett says. On arrival, ship captains found no waiting cargo or passengers to justify a return journey—and besides, they and their crew were eager to try their own luck in the gold fields. The ships weren’t necessarily abandoned—often a keeper was hired to keep an eye on them, Everett says—but they languished and began to deteriorate. The daguerreotype above, part of a remarkable panorama taken in 1852, shows what historians have described as a “forest of masts” in Yerba Buena Cove.

Sometimes the ships were put to other uses. The most famous example is the whaling ship Niantic, which was intentionally run aground in 1849 and used as a warehouse, saloon, and hotel before it burned down in a huge fire in 1851 that claimed many other ships in the cove. A hotel was later built atop the remnants of the Niantic at the corner of Clay and Sansome streets, about six blocks from the current shoreline (see map at top of post).

A few ships were sunk intentionally. Then as now, real estate was a hot commodity in San Francisco, but the laws at the time had a few more loopholes. “You could sink a ship and claim the land under it,” Everett says. You could even pay someone to tow your ship into position and sink it for you. Then, as landfill covered the cove, you’d eventually end up with a piece of prime real estate. All this maneuvering and the competition for space led to a few skirmishes and gunfights.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

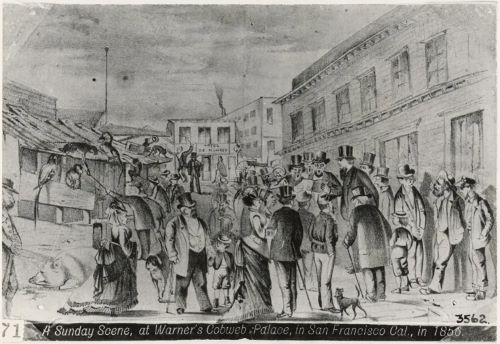

Oyster Pirates in the San Francisco Bay

Once a key element in Native economies of the region, clams and oysters became a reliable source of free protein for working-class and poor urban dwellers.

At the start of the twentieth century, there were pirates operating in the San Francisco Bay: oyster pirates. Shellfish had been part of the Indigenous economy before the arrival of European settlers, but commercial oyster farming had become a big industry by the late 1800s. Commercial oyster beds were valuable, and pirates visited by night to steal the oysters in them.

Meanwhile the oyster bed owners had paid for the land and to seed the beds (with East Coast oysters), so they were losing expensive property. It was a challenge for law enforcement, because a purloined oyster looked the same one that had grown on an abandoned bed and was free for anyone to take.

As historian Matthew Morse Booker asks in the Pacific Historical Review, “At stake were persistent questions in American history: Who should have access to natural resources? To whom did the bay belong?”

Once a key element in Native economies of the region, clams and oysters were a reliable source of free protein for working-class and poor urban dwellers. But the arrival of commercial industry blocked private use of theoretically communal resources. And the oysters illustrated a bigger historical issue, beyond the San Francisco Bay. As Booker explains, “Everywhere in the industrializing nineteenth-century world, poor people lost access to traditional common lands and the products they had gathered there. This loss was contested.”

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT JSTOR DAILY

The Monkeys and Parrots Caught Up in the California Gold Rush

Researchers combed through 19th-century records and found evidence of the species, which joined a menagerie that included Galapagos tortoises and kangaroos.

In March 1853, after sailing seven weeks straight from Nicaragua, 5 monkeys and 50 parrots reached San Francisco. Caged on the wharf, chattering and squawking, the animals likely drew a crowd. Perhaps some onlookers gathered to admire the parrots’ plumage, which added flashes of scarlet and lime-green to this spring day. Other folks may have expected the monkeys to put on a show, like the primates they knew from childhood circuses and stories.

The captive creatures wound up as pets and street attractions, meant to entertain San Francisco’s flood of newcomers, who came hoping to profit from the Gold Rush. Some monkeys sported blazers, cranked hand organs and—as one 19th-century newspaper put it—did “all the usual antics performed by monkeys.” Parrots mainly served as pets, so prized that lost birds were reported in classified ads—like a listing from one Mrs. Ross offering a $50 reward (about $1,900 today) for her missing parrot, Pretty Joey Ross.

New research has uncovered evidence of these animals, which were stolen from their wild habitats and hauled to San Francisco in the 1850s. Details on the importers are sparse, but some probably nabbed the creatures, opportunistically, as their ships ferried U.S. East Coasters around the southern landmasses, en route to San Francisco. Other enterprising merchants made trips especially for marketable goods—including live fauna—from Central and South America. To shed light on the animal trade, Cyler Conrad, an archaeologist at Los Alamos National Laboratory and the University of New Mexico, dug through archives of historical documents and archaeological finds. His findings, published in March in Ethnobiology Letters, detailed how city-dwellers used imported monkeys and parrots for amusement.

These unwitting pets now join a growing list of animals affected by the Gold Rush. The list includes Tule elk, a species only found in California that miners hunted from abundance to near extinction. Fewer than 30 elk remained in 1895, and thanks to later laws the population has climbed back to around 5,700 individuals today. Also among the animal causalities, giant tortoises captured live in the Galapagos Islands were shipped to San Francisco and cooked into steaks, stews and pies. At the time, the tortoise numbers were already dangerously low due to whalers’ appetites earlier that century. The Gold Rush demand for tortoise meat pushed the creatures closer to the brink; today they remain on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. By adding these animals to Gold Rush history, Conrad and others are rendering a fuller—and grimmer—picture of both the period’s ethos and its ecological toll.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT SMITHSONIAN MAGAZINE

I Retraced the Gold Rush Trail to Find the American Dream

A disenchanted San Franciscan rides west with a motley crew of pioneers.

Day 1: Zephyr Cove, Nevada, to Meyers, California

Distance: 13 miles. 22 minutes by car; 6 hours by wagon

The road I traveled was lined with the bodies of dead pioneers. Among the 300,000 mostly luckless treasure seekers, they were the most unlucky, casualties of their own dreams. In 1849 they’d lit out for California, the great prize of the Mexican-American war, after President James K. Polk confirmed that gold was plentiful. His State of the Union speech launched thousands of wagons, the greatest mass migration in American history, and for one week in early summer, I followed their path—at three miles per hour.

The assignment was as exceptional, fanciful, and unsound as my final destination: San Francisco. My beloved city has always attracted risk takers, misfits, dreamers, and entrepreneurs, but the gears in Northern California’s boom-and-bust culture have stalled. Diversity-minded countercultures working toward meaningful change have literally lost ground to a capital-driven tech industry and its outrageous claims about saving the world.

I don’t know what it’s like to see San Francisco as a city making good on the promise of the New World, but I was desperate to find out. Playing at this, like William Faulkner and Shelby Foote’s rumored battlefield visits at Shiloh (fueled by “walking whiskey”), wouldn’t be enough. I could not proceed as a detached or bemused observer. I had to shed my thoroughly cultivated adult cynicism and throw myself into this masquerade with the sincerity of a child. I needed to believe in the dream.

I’m not the only one. This was the sixty-sixth time the Highway 50 Association had led a train of Conestoga wagons, stagecoaches, and horseback riders down “Roaring Road,” one of the major land routes to Gold Country—from Zephyr Cove, Nevada, to Placerville, California—retracing the treasure seekers’ route.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE NEW REPUBLIC

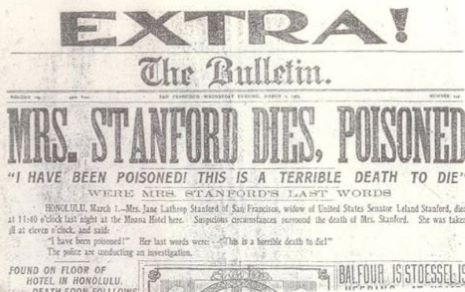

The Robber Baroness of Northern California

Authorities who investigated Jane Stanford’s mysterious death said the wealthy widow had no enemies. A new book finds that she had many.

The life of Leland Stanford is the stuff of legend: the journalist Matthew Josephson popularized the term “robber baron” in his 1934 book about Gilded Age capitalists to describe Leland and his peers. “It was said of him that ‘no she-lion defending her whelps or a bear her cubs will make a more savage fight than will Mr. Stanford in defense of his material interests,’ ” Josephson wrote. Others heralded Leland as a talented entrepreneur, his railroads as the engines of American economic progress. Jane Stanford never received such extravagant praise nor such harsh censure. When she died suddenly in a Hawaii hotel room, in 1905, an obituary reported that her greatest happiness was caring for her home. Leland was a mother bear; Jane was just a mother.

That view shaped the investigation that followed her death. When a violent spasm threw her from her bed, Stanford had told the doctor who rushed to her care, “I have been poisoned.” Newspapers widely reported those words, as well as the results of an autopsy that found traces of strychnine in her blood. In the end, though, authorities insisted that Stanford could not have been murdered, for the kindly widow had no enemies. But, as the historian Richard White finds in his engaging new book “Who Killed Jane Stanford?,” she had many.

Jane Stanford’s first biographer was her live-in personal secretary, Bertha Berner. The Berners, a German immigrant family, had moved to Northern California when Bertha was nineteen, for her mother Maria’s health. Shortly after they arrived, in 1884, the Berner family learned of the death of the Stanfords’ only child, Leland, Jr. Attending the funeral, the Berners were moved by the Stanfords’ grief and by the size of the crowd. Bertha Berner wrote to Stanford afterward to offer her dictation services; her mother had observed that the Governor’s wife’s eyes looked “wept blind.”

In “Mrs. Leland Stanford: An Intimate Account” (1935), Berner described her “prominent and much loved” employer as someone who shied away from public attention. The daughter of a wealthy merchant from Albany, New York, Jane Stanford had followed her entrepreneurial husband west to Port Washington, Wisconsin, where he sought to make his way as a lawyer. When a fire destroyed Leland, Sr.,’s legal library, she stood by his side while he re-invented himself in California, first in the railroad business, and then in politics. She also served as a muse for her husband’s innovations—it was supposedly her seasickness on a long trip from Albany to San Francisco via the Isthmus of Panama that inspired Leland to build the transcontinental railroad.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE NEW YORKER

When California Went to War Over Eggs

As the Gold Rush brought more settlers to San Francisco, battles erupted over the egg yolks of a remote seabird colony

It was the aftermath of the California Gold Rush that instigated the whole hard-boiled affair.

The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in 1848 triggered one of the largest mass migrations in American history. Between 1848 and 1855, some 300,000 fortune-hunters flocked to California from all over the world in hopes of finding gold. Ships began pouring into the San Francisco Bay, depositing an endless wave of gold-seekers, entrepreneurs, and troublemakers. As the gateway to the goldmines, San Francisco became the fastest growing city in the world. Within two years of the 1848 discovery, San Francisco’s population mushroomed from around 800 to over 20,000, with hundreds of thousands of miners passing through the city each year on their way to the gold fields.

The feverish growth strained the area’s modest agriculture industry. Farmers struggled to keep up with the influx of hungry forty-niners and food prices skyrocketed. “It was a protein hungry town, but there was nothing to eat,” says Eva Chrysanthe, author of Garibaldi and the Farallon Egg War. “They didn’t have the infrastructure to feed all the hungry male workers.”

Chicken eggs were particularly scarce and cost up to $1.00 apiece, the equivalent of $30 today. “When San Francisco first became a city, its constant cry was for eggs,” a journalist recalled in 1881. The situation became so dire that grocery stores started placing “egg wanted” advertisements in newspapers. An 1857 advertisement in The Sonoma County Journal read: “Wanted. Butter and Eggs for which the highest price will be paid.”

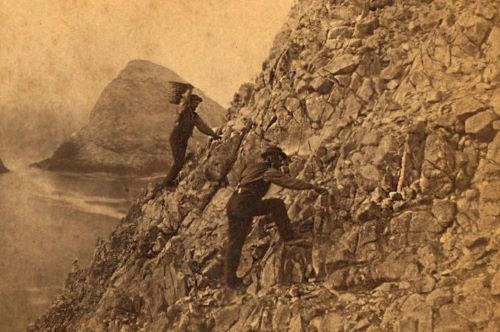

The scramble for eggs drew entrepreneurs to an unusual source: a 211-acre archipelago 26 miles west of the Golden Gate Bridge known as the Farallon Islands. The skeletal string of islets are outcroppings of the continental shelf, made up of ancient, weather-worn granite. “They are a very dramatic place,” says Mary Jane Schramm of the Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary. “They look…like a piece of the moon that fell into the sea.”

Though the islands are inhospitable to humans—the Coast Miwok tribe called them ‘the Islands of the Dead’—they have long been a sanctuary for seabirds and marine mammals. “I can’t overstate the dangers of that place and how hostile it is to human life,” says Susan Casey, author of The Devil’s Teeth: A True Story of Obsession and Survival Among America’s Great White Sharks. “It’s a place where every animal thrives because it’s the wildest of the wild, but it’s a tough place for humans.”

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT SMITHSONIAN MAGAZINE

How Private Capital Strangled Our Cities

By following the money, a new history of urban inequality turns our attention away from federal malfeasance and toward capital markets and financial instruments.

Credit and debt, two sides of the same proverbial coin, place a bet on time. Credit makes money mobile and funds the future. Soon enough, however, it becomes debt, with the lender demanding from the borrower returns with interest that threaten to constrict the possibility of further credit. Personal debt masquerades as moral obligation, a contract freely chosen, yet at the heart of the promise debt creates is not social reciprocity, as the late David Graeber wrote in Debt: The First 5000 Years, but a “simple, cold, and impersonal” market transaction. As nothing more than a “matter of impersonal arithmetic,” debt requires shame and ultimately the threat of force to fulfill its terms and realize the returns for creditors it promises. It lodges coercion at the heart of the supposedly “free” market.

The squeeze is only intensified in the seemingly impersonal world of institutional finance. If debt ensures stability and solvency for some, the economic growth it propels fuels dependency and inequality for others, not only between creditor and debtor but also further down the line, as the borrower passes on the costs of debt to those with less power to control the terms of the deal. This devil’s bargain is particularly true when it comes to municipal debt, argues the Stanford University historian Destin Jenkins in The Bonds of Inequality, his new book on the power the bond market has leveraged over San Francisco and other US cities. The debt-financed spending that cities have long used to spur growth, Jenkins contends, has also underwritten the racial and income inequality of the post–World War II metropolis, while funneling profits to bankers and reinforcing city dependency on finance capitalism. This unequal compact hid in plain sight until the 1970s, when the urban fiscal crises of the era revealed that cities were deeply in hock to financial institutions. But debt was just the way business was done, and banks and other lenders saw no reason to ease the terms of this deal, preferring instead to underwrite the continued hollowing-out of the American metropolitan landscape.

The Bonds of Inequality jumps off from 40 years or so of work by urban historians exposing the platitudes conservatives and liberals used to explain the “urban crisis” that began in the 1960s. Not long ago, the conventional wisdom about urban life in the years after World War II unfurled in a series of overdetermined catchphrases. Cities, peaceful and prosperous through the 1950s and early ’60s, “went downhill” after the riotous “long hot summers” and “white flight” of the late ’60s. The cause of this urban collapse, conservative and liberal piety of the ’80s and ’90s assured us, was not a lack of money in cities but too much: Overeager liberals, looking to usher in Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society with War on Poverty programs, welfare payments, and other instruments of social engineering, supposedly created a permanent “underclass” living in a “culture of poverty.” The only way to end these so-called cycles of “dependency” was, as Bill Clinton did in the ’90s, to “end welfare as we know it” and “get tough on crime.”

Urban historians have long shown these easy judgments to be disconnected from life on the ground. Taking their cues from neighborhood and labor organizers, civil rights lawyers and fair housing campaigners, as well as many in the Black and Latinx community who have resisted the ill effects of this consensus all along, these historians have unearthed the fact that white Americans, working- and middle-class alike, were the primary recipients of postwar government dollars. They followed federal subsidies to the suburbs, while government policy neglected Black and Latinx neighborhoods. Far more important than government welfare was government support for urban deindustrialization, urban renewal and “slum” clearance, highway building, and segregated and underfunded public housing. Less the beneficiaries of federal largesse, Black and Latinx urban dwellers were simply left behind by a postwar welfare state that systematically overdeveloped suburbs and underdeveloped cities, leaving behind the racialized and bifurcated metropolitan landscape of George Floyd’s America.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE NATION

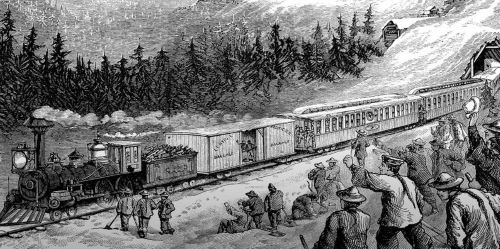

What Was It Like to Ride the Transcontinental Railroad?

The swift, often comfortable ride on the Transcontinental Railroad opened up the American West to new settlement.

Velvet cushions and gilt-framed mirrors. Feasts of antelope, trout, berries and Champagne. In 1869, a New York Times reporter experienced the ultimate in luxury—and he did so not in the parlor of a Gilded Age magnate, but on a train headed from Omaha, Nebraska to San Francisco, California.

Just a few years before, the author would have had to rely on a bumpy stagecoach or a covered wagon to tackle a journey that took months. Now, he was gliding along the rails, passing by the varied scenery of the American West while dining, sleeping and relaxing.

The ride was “not only tolerable but comfortable, and not only comfortable but a perpetual delight,” he wrote. “At the end of our journey [we] found ourselves not only wholly free from fatigue, but completely rehabilitated in body and spirits. Were we very far from wrong if we voted the Pacific Railroad a success?”

The author was just one of the thousands of people who flocked to the Transcontinental Railroad beginning in 1869. The railroad, which stretched nearly 2,000 miles between Iowa, Nebraska and California, reduced travel time across the West from about six months by wagon or 25 days by stagecoach to just four days. And for the travelers who tried out the new transportation route, the Transcontinental Railroad represented both the height of modern technology and the tempting possibility of unrestricted travel.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT HISTORY

On Upward Mobility

Research shows the neighborhood you grow up in has profound impact on your future economic success. How did my family’s journey across the country impact me?

“I don’t think you’d be the same person had we stayed in L.A.,” my mom told me recently. “I wanted you to have better opportunities.”

About a year ago, I moved back to my birthplace, Los Angeles. The move came after six years on the east coast and a desire to be closer to my family.

It’s weird coming back to a place so familiar yet foreign. Despite being born in L.A., and raised just south of the city, I moved to the San Francisco Bay Area when I was 7, rendering Los Angeles a relic of my childhood, a menagerie of foggy memories.

It’s unclear what my mom meant by “better opportunities.” Still, I got the gist that it was about the socioeconomic measures think tanks, policymakers and researchers use to measure progress: education, housing and income.

I thought, “can I actually measure if moving made a difference?” Indeed, your environment impacts your future outcomes, but to what extent?

In March of 2018, Raj Chetty, an economist at Harvard, and a team of researchers sought to estimate upward mobility across socioeconomic lines. Using anonymized Census data and tax records of roughly 20 million Americans, he and his team predicted outcomes for children born between 1978 and 1983 to when they were in their 30s (around 2015).

Among Chetty et al.’s findings was the importance of geographical location.

Research showed that outcomes for children could vary widely even when their neighborhoods were as little as a mile apart. Furthermore, the age at which someone moves profoundly impacts their future earnings but only up until a limit.

I was born in 1989, so I was curious—what were my expected outcomes at birth? And, what would’ve happened had I been born somewhere else?

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE PUDDING

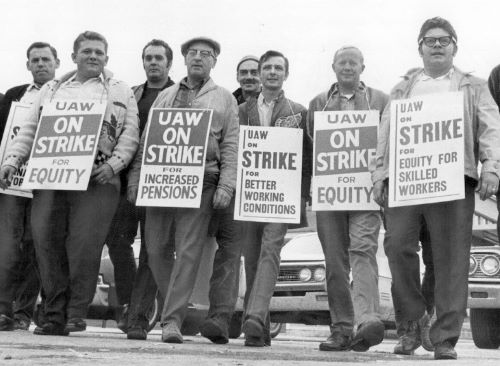

Nelson Lichtenstein on a Half-Century of American Class Struggle

The esteemed labor historian reflects on his life and career, including Berkeley in the 1960s, Walter Reuther, the early UAW, Walmart, Bill Clinton, and more.

Lichtenstein is among the greatest living American labor historians. In a long conversation with Jacobin editor Micah Uetricht covering his life and career, Lichtenstein discusses his life and education at the University of California (UC), Berkeley, in the midst of that campus’s many eruptions in the 1960s; the intellectual and activist influence of his membership in the International Socialists (IS), a Trotskyist organization; his years studying the early United Auto Workers (UAW) and Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO); his later turn to studying Walmart and international supply chains; his continued appreciation for radical politics and radical activists organizing, despite leaving Trotskyism behind; his thoughts about the state of labor history; and much more.

Lichtenstein spoke with Uetricht for the Jacobin podcast The Dig in March 2023; you can listen to the episode here. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

MICAH UETRICHT

You write in your essay collection, A Contest of Ideas, about being the son of a German Jew who fled the Nazis during World War II and an American mother who fled Mississippi around the same time. You came of age during the civil rights movement era. Is that how you were first politicized?

NELSON LICHTENSTEIN

At the dinner table, my father was sort of a social democrat. My mother was hostile to the Gothic South even before the civil rights movement, but yes, the civil rights movement was a defining moment for everyone in my generation. I didn’t go to Mississippi in ’62 or ’63 but I did end up in Alabama in the summer of ’66. It was extraordinarily important.

My father ran this five-and-dime store in Frederick, Maryland, which is sort of a border state. And you could see the racial dynamics of the clientele and the sales staff. The town was segregated. I came of age just as desegregation was taking place.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT JACOBIN

Immigration

How a California Archive Reconnected a New Mexico Family with its Chinese Roots

Aimee Towi Mae Tang’s Chinese American family never talked about the past. She decided to change that.

On a bright afternoon in March 2021, Aimee Towi Mae Tang was curled up on her couch in Irvine, California, reading a book she’d chosen for her then-13-year-old daughter Marisol’s homeschool curriculum. Aimee had taken over Marisol’s education, frustrated by the narrow view of the world taught in public school and what she called its “European American bias.” Then a news alert lit up her phone: A gunman had shot and killed eight people at Atlanta-area spas. Six of them were Asian women.

For Aimee, a fourth-generation Chinese New Mexican and a citizen of Jemez Pueblo, the tragedy echoed the discrimination and violence her family has experienced. In the 1930s, state laws barred Edward Gaw, her great-grandfather, from buying land in Albuquerque, New Mexico. During the 1980s, when she was in high school, boys harassed her, shouting a gendered slur common in American films about the Vietnam War. When Aimee saw videos of Asian elders being attacked and beaten in late 2020 during a rise in anti-Asian hate crimes, she thought of her own father, who was then 76.

Three weeks after the Atlanta shootings, I found myself on the phone with Aimee, talking about the nation’s shocked reaction. Aimee’s usually tender voice hardened. “You’ve ignored your cancer for years, and now, at stage 4, you go to the doctors and ask, ‘Oh, how is this happening?’” she said. “Well, come on! If that’s how you’ve treated the Chinese, how is this not happening?”

Aimee’s father and grandparents spoke fluent Cantonese, but her family raised her to fit in with white American society. “We never talk about China. We speak English in our household. We eat Chinese food with a fork and knife,” she said.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT HIGH COUNTRY NEWS

We’ve Been Here Before: Historians Annotate and Analyze Immigration Ban’s Place in History

Six historians unpack the meaning of President Trump’s controversial executive order.

Context matters.

And the context of Trump’s executive orders on immigration are a long history of excluding immigrants on the basis of national origin, political and religious beliefs and in the name of national security.

Enter historians. One week ago, a group affiliated with the Immigration History Research Center at the University of Minnesota and the Immigration and Ethnic History Society created #immigrationsyllabus. It’s an attempt to bring facts and understanding to our current immigration debates. The syllabus is an organized set of readings that brings clarity to a very complex system, but also makes it clear that these debates have been going on since the founding of the United States.

And to be clear, it’s nonpartisan. These are all long-standing, published and peer-reviewed scholars.

These historians have come together again to help us understand Trump’s executive orders on immigration. The order he signed Friday gave federal agencies broad power to detain or deny entry to anyone arriving as a refugee from any country or as an immigrant of any kind from the so-called “countries of concern,” Iraq, Syria, Iran, Sudan, Libya, Somalia and Yemen.

We’ve been covering the effects of the order, perspectives on what it does and what it’s for, as well as the lawsuits that have arisen in result. But here is the order itself, annotated by six historians from universities around the US.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE PRI THEWORLD

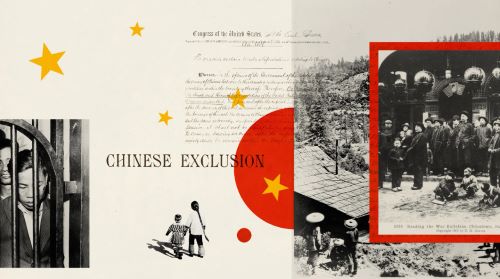

The Photos Left behind From the Chinese Exclusion Era

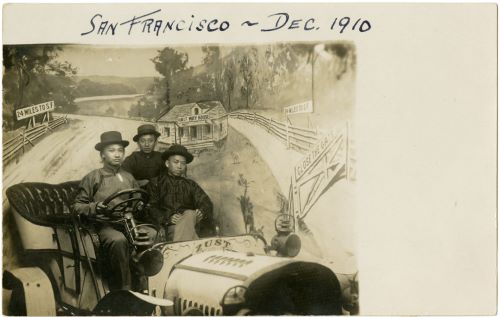

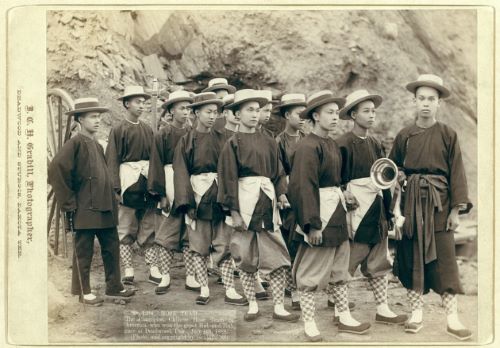

The California Historical Society contrasts how Chinese people were portrayed in the press with the dignified studio portraits taken in Chinatown.

In one room of the exhibition Chinese Pioneers: Power and Politics in Exclusion Era Photographs at the California Historical Society, studio portraits of Chinese people in late-1800s San Francisco share space with candid photos by Arthur Genthe. San Francisco’s Chinatown fascinated Genthe, who would go there, hiding his camera under his coat. Genthe wrote about his subjects as “unsuspecting victims,” and in one of his photos, the subject holds up his hands to shield his face.

Curator Erin Garcia observes how Genthe defined how the subjects were seen, and sometimes went so far as to title them, as in “A Slave Girl in Holiday Attire” on the photo of one woman, and “Young Aristocrats” on a photo of children. In contrast, in the posed studio portraits, the subjects decided how to present themselves.

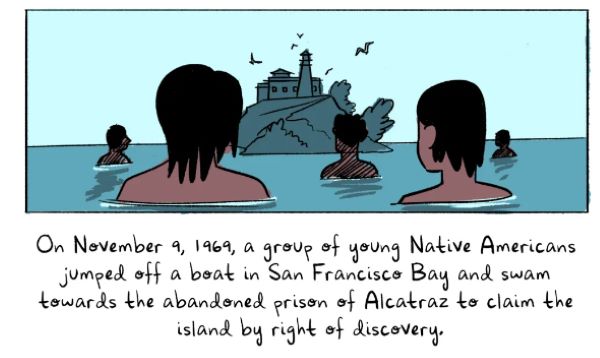

Garcia wanted to show these sorts of disparities in this visual history of the years around the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, a law that banned immigration and prevented people from becoming citizens. In the first gallery of the exhibition, we see editions of the San Francisco Illustrated Wasp, which show racist and grotesque cartoons caricaturizing Chinese people; an issue of the national Harper’s Weekly with a cartoon showing the San Francisco Customs House with a long line of Chinese people; and a lithograph from the Workingmen’s Party of California, with their slogan “The Chinese Must Go!” The party, Garcia says, successfully ran state candidates and spurred anti-Chinese state legislation, which paved the way for the Exclusion Act.