Greenland’s modern history stands as a sustained counterexample to the older assumption that strategic necessity inevitably leads to territorial possession.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Power after Conquest

The end of World War II marked a decisive rupture in the long history of territorial politics. The devastation of global conflict discredited conquest as a legitimate instrument of statecraft, replacing older imperial logics with a new international consensus grounded in sovereignty, self-determination, and collective security. This shift did not eliminate power politics, but it fundamentally altered how power was exercised and justified. States continued to pursue strategic advantage, yet they increasingly did so without claiming ownership of territory. Greenland’s modern history unfolds squarely within this transformed landscape.

Greenland entered this postwar order not as a prize seized through force, but as a space rendered strategically indispensable by circumstance. The island’s geographic position had long been known, but its strategic value intensified with the emergence of global warfare, long-range aviation, and nuclear deterrence. During and after World War II, Greenland became essential to transatlantic defense and Arctic surveillance. Yet at no point did this importance translate into formal annexation or transfer of sovereignty. Instead, Greenland exemplified a new model of power projection: access without ownership, presence without possession.

This distinction mattered deeply. Earlier centuries had treated strategic necessity as justification for territorial acquisition, collapsing security into sovereignty. The post-1945 order rejected that equivalence. Military basing agreements, alliance structures, and international law created mechanisms through which states could secure their interests while respecting existing political boundaries. Greenland’s relationship with the United States and NATO reflected this logic. Security concerns were addressed through partnership and infrastructure, not through claims of entitlement. The island remained politically Danish and, increasingly, Greenlandic, even as it became integral to Western defense.

Understanding Greenland’s modern role therefore requires attention to what did not happen as much as to what did. No conquest followed strategic discovery. No doctrine transformed access into ownership. For decades, Greenland stood as evidence that great power competition could coexist with restraint, that strategic value need not negate sovereignty. This postwar settlement now appears increasingly fragile. Contemporary rhetoric that treats Greenland as an object of acquisition represents not continuity with Cold War practice, but a regression to prewar assumptions. To grasp the significance of that shift, one must first understand the postwar order that made Greenland strategically vital without ever making it a possession.

World War II and the Strategic Awakening of Greenland

Greenland’s entry into modern power politics was precipitated not by ambition but by emergency. The German occupation of Denmark in April 1940 abruptly severed Greenland from its metropolitan government, exposing the island’s vulnerability and strategic importance. Cut off from direct Danish control, Greenland faced the prospect of becoming a foothold for Axis expansion in the North Atlantic. Its geographic position, once peripheral, now appeared central to the defense of transatlantic shipping lanes and the security of North America itself.

The United States responded through a series of pragmatic arrangements rather than overt assertion of sovereignty. In 1941, American officials negotiated agreements with Danish representatives in exile that authorized U.S. forces to defend Greenland and establish military installations. These agreements were explicitly framed as temporary and protective, grounded in necessity rather than entitlement. Greenland was treated as a space requiring defense, not as territory available for acquisition. Even at a moment of extraordinary leverage, the United States refrained from converting strategic access into political possession.

Military activity during the war transformed Greenland’s functional role. Airfields, weather stations, and supply routes were established to support Allied operations, particularly the ferrying of aircraft to Europe and the monitoring of North Atlantic conditions. Greenland became a critical node in an emerging system of global warfare that depended on speed, coordination, and information. Yet these developments remained embedded within alliance logic. The emphasis was on contribution and coordination, not control. Greenland’s strategic awakening did not entail a redefinition of its political status.

The wartime experience set a powerful precedent for the postwar order. Greenland demonstrated that strategic necessity could be addressed through cooperation rather than conquest. The United States exercised significant influence on the island, but it did so within an explicitly limited framework that preserved Danish sovereignty and anticipated eventual restoration of normal governance. World War II thus marked Greenland’s transformation into a strategic asset without reviving older imperial patterns. This model of access without annexation would shape Cold War policy and stand as a quiet rebuke to later claims that security imperatives naturally justify territorial acquisition.

The Cold War Arctic and the Logic of Forward Defense

The onset of the Cold War transformed Greenland’s strategic significance from wartime contingency to permanent feature of global security planning. As tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union hardened into ideological and military rivalry, geography assumed renewed importance. The Arctic emerged as the shortest route between superpowers, collapsing distance through the logic of air power and ballistic trajectories. Greenland’s location placed it squarely along this axis, making it indispensable to early warning systems and continental defense. Strategic value no longer depended on commerce or settlement but on proximity to potential attack.

American defense planning embraced a doctrine of forward defense that sought to detect and deter threats as far from the continental United States as possible. Greenland fit this logic precisely. Radar installations, airfields, and communications infrastructure were designed to provide advance notice of Soviet aircraft or missile launches, buying precious minutes in the event of attack. The island became part of an integrated security architecture extending across the Arctic, linking Alaska, Canada, and northern Europe. Crucially, this system treated Greenland as infrastructure rather than territory, a platform for defense rather than an object of possession.

This distinction reflected broader postwar norms. The United States pursued extensive basing rights around the world yet rarely sought formal sovereignty over host territories. Forward defense depended on alliances, agreements, and mutual recognition rather than annexation. In Greenland’s case, Danish sovereignty was not an obstacle but a stabilizing factor. As a NATO ally, Denmark provided legal and political legitimacy for American presence, embedding Greenland’s strategic role within a multilateral framework that contrasted sharply with earlier imperial practices.

The Arctic also reshaped military thinking itself. Unlike traditional theaters of war, it offered no civilian population centers to occupy and no political institutions to capture. Its value lay in detection, deterrence, and surveillance rather than control. Greenland exemplified this shift. The island was essential not because it could be governed or exploited, but because it enabled systems that operated far beyond its shores. This functional logic reinforced the separation of security from sovereignty that defined Cold War strategy.

By embedding Greenland within a network of forward defense, the Cold War confirmed a new model of power projection. Strategic necessity justified presence, but not ownership. Access was secured through consent and alliance rather than conquest. This arrangement endured for decades, shaping expectations about how great powers behaved in strategically sensitive regions. Greenland’s Cold War role thus stands as evidence that even at the height of existential rivalry, restraint remained possible. Power could be exercised intensely without reverting to the territorial ambitions that had defined earlier eras.

Thule Air Base and the Architecture of Deterrence

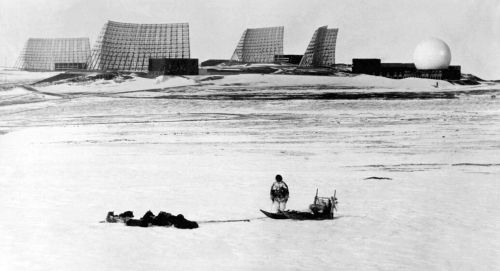

The construction of Thule Air Base (renamed Pituffik Space Base in 2023) in the early 1950s represented the most concrete expression of Greenland’s integration into Cold War deterrence architecture. Situated in northwest Greenland, Thule was designed to support long-range strategic aviation, missile warning systems, and later ballistic missile defense. Its location allowed the United States to monitor Soviet activity across the polar region and to embed Greenland within an emerging network of early warning and response. Thule was not conceived as a base for territorial control. It was a node in a larger system whose purpose lay elsewhere, oriented toward anticipation rather than occupation.

The base embodied the technological logic of deterrence. Radar arrays, satellite tracking facilities, and communications infrastructure transformed Greenland into a site of constant observation. Security depended on speed and information, not on the projection of authority over local populations. Thule’s significance was measured in minutes and data streams rather than in land administration. This emphasis reinforced the postwar separation between strategic value and political sovereignty. Greenland mattered because it enabled deterrence, not because it could be absorbed into the American state.

Legal and diplomatic arrangements surrounding Thule further underscored this distinction. U.S. access was secured through agreements with Denmark that explicitly preserved Danish sovereignty and situated the base within NATO’s collective defense framework. Even as the American presence became permanent in practice, it remained politically conditional. The base existed by consent rather than claim, a sharp contrast to earlier eras in which military necessity routinely justified annexation. Thule demonstrated that permanence of use did not require permanence of possession.

Yet the architecture of deterrence also revealed the asymmetries embedded in this model. Decisions about base construction, expansion, and function were largely made by distant authorities, with limited input from Greenlandic communities. While sovereignty remained formally intact, power operated unevenly. Thule thus illustrates both the strengths and the tensions of postwar restraint. It showed that strategic dominance could coexist with legal sovereignty, even as it exposed the limits of participation within that arrangement. The base became a symbol not of conquest, but of a new form of power that relied on infrastructure, alliance, and technological reach rather than territorial absorption.

Indigenous Greenlanders, Autonomy, and Postwar Political Change

The postwar period gradually reoriented Greenland’s political trajectory away from colonial administration and toward Indigenous self-determination. During World War II and the early Cold War, strategic imperatives had largely sidelined local political participation, reinforcing patterns in which decisions about Greenland were made elsewhere. Yet the same global transformations that delegitimized conquest also undermined colonial governance. Decolonization movements worldwide reshaped political expectations, and Greenland was not immune to this shift. The island’s strategic importance persisted, but its political status became increasingly contested and renegotiated.

In the decades after 1945, Danish policy toward Greenland began to change under pressure from both international norms and internal critique. Greenland’s formal integration into the Danish state in 1953, replacing its colonial status, marked an attempt to modernize governance while preserving metropolitan authority. This transition expanded social services and political representation, but it did not fully address questions of autonomy or cultural recognition. Greenlanders remained subject to decisions shaped by strategic and economic considerations in which they exercised limited control.

Indigenous political mobilization gained momentum in the latter half of the twentieth century. Education, urbanization, and exposure to global Indigenous movements fostered new forms of political consciousness. Greenlandic leaders increasingly challenged paternalistic governance and demanded greater control over local affairs. These demands were not framed as rejection of security cooperation or alliance membership, but as insistence that strategic relevance should not eclipse political agency. The coexistence of military importance and political marginalization became increasingly untenable.

The introduction of Home Rule in 1979 marked a decisive shift. Authority over domestic affairs was transferred to a locally elected government, establishing Greenland as a political community rather than merely a strategic platform. This arrangement acknowledged the legitimacy of Indigenous governance while maintaining Denmark’s responsibility for defense and foreign policy. Three decades later, the Self-Government Act of 2009 further expanded autonomy, recognizing Greenlanders as a distinct people under international law with the right to self-determination. These reforms re-centered sovereignty within Greenlandic society, even as strategic cooperation with the United States and NATO continued.

This postwar evolution underscores a crucial distinction. Greenland’s growing autonomy did not undermine its strategic role, nor did its strategic role invalidate its political development. Security and self-determination advanced in parallel, demonstrating that strategic necessity need not suppress Indigenous agency. The gradual reassertion of Greenlandic political voice stands as one of the most significant outcomes of the postwar order. It represents a departure from earlier eras in which strategic value routinely erased local sovereignty, and it forms a central contrast to contemporary rhetoric that once again treats Greenland as an object rather than a polity.

The Post-1945 Norm: Security without Sovereignty

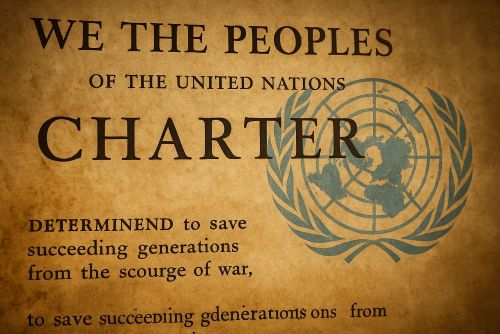

The international order that emerged after 1945 rested on a profound redefinition of legitimacy in world politics. The devastation of World War II discredited territorial conquest as an acceptable means of resolving security concerns. In its place arose a framework centered on sovereign equality, territorial integrity, and collective security. The United Nations Charter codified these principles, embedding them in international law and diplomatic practice. While power politics did not disappear, the overt acquisition of territory through force became broadly illegitimate, constrained by legal norms and political expectation.

This shift did not eliminate strategic competition. Instead, it altered the methods through which states pursued advantage. Military basing agreements, alliance systems, and security partnerships replaced annexation as the primary tools of influence. States sought access rather than ownership, presence rather than possession. This distinction was critical. By separating security from sovereignty, postwar norms allowed major powers to project force and deter rivals without unraveling the legal order that underpinned international stability. Greenland became one of the clearest demonstrations of this logic in practice.

The United States played a central role in institutionalizing this norm. Across Europe, Asia, and the Pacific, American security strategy relied on a global network of bases operating within the territories of sovereign allies. These arrangements were justified as mutual defense rather than imperial control. Host states retained formal sovereignty, even as American military presence became extensive and enduring. The legitimacy of this system depended on consent, treaty obligations, and alliance structures, distinguishing it sharply from earlier eras of colonial domination.

Greenland fit seamlessly into this model. Its strategic value was undeniable, yet its political status remained untouched. Defense agreements with Denmark preserved sovereignty while enabling robust military cooperation. The United States exercised immense operational influence on the island without asserting legal claim to it. This restraint was not accidental. It reflected a widely shared understanding that security imperatives, however pressing, did not override the political rights of states or peoples. Greenland’s role demonstrated that even in strategically sensitive regions, restraint could coexist with effectiveness.

International law reinforced this separation. The prohibition of aggressive war, the norm against territorial acquisition by force, and the principle of self-determination created a dense legal environment in which annexation carried significant diplomatic and reputational costs. Strategic necessity alone was insufficient to justify ownership. Even superpowers operated within these constraints, aware that violating them risked destabilizing the broader order from which they benefited. Greenland’s continued political integrity was thus not merely a matter of bilateral preference, but a product of systemic norms.

The durability of the post-1945 norm lay in its practicality. It offered a way to reconcile power with order, allowing states to pursue security without dismantling the legal foundations of international society. Greenland stands as a testament to that balance. For decades, it remained strategically vital without becoming a prize to be claimed. The erosion of this norm in contemporary rhetoric is therefore not a minor departure. It represents a challenge to one of the central compromises of the postwar world, one that separated access from ownership and power from entitlement.

Arctic Competition after the Cold War

The end of the Cold War did not diminish Greenland’s strategic relevance, but it altered the terms under which Arctic competition unfolded. With the collapse of bipolar confrontation, the Arctic briefly appeared to recede from the forefront of security planning. Military installations were reduced, rhetoric softened, and cooperation expanded through scientific, environmental, and diplomatic channels. Yet this apparent lull masked a deeper continuity. The Arctic remained geopolitically significant, even as the nature of competition shifted from immediate military threat to long-term strategic positioning.

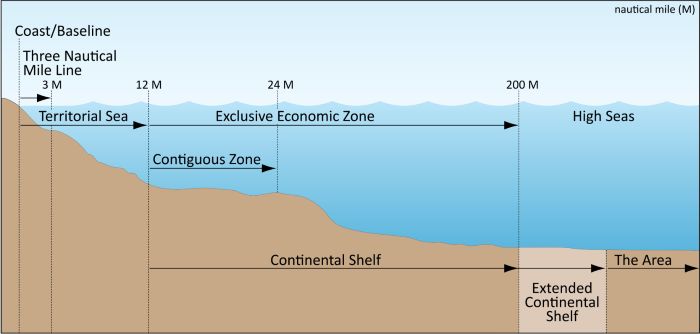

Climate change became the central catalyst for renewed attention. Melting sea ice opened previously inaccessible shipping routes and raised the prospect of resource extraction across the Arctic basin. These developments transformed the region into a space of economic and strategic anticipation rather than immediate confrontation. States began to plan not for imminent conflict but for future advantage, investing in infrastructure, research, and legal claims. Importantly, this competition unfolded within existing legal frameworks. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea provided mechanisms for asserting maritime rights without recourse to territorial seizure, reinforcing the post-1945 separation between access and ownership.

Greenland occupied a distinctive position within this emerging landscape. Its geographic location made it central to Arctic transit routes and surveillance networks, while its political status as a self-governing territory within the Kingdom of Denmark anchored it firmly within the existing international order. Strategic interest in Greenland intensified, but it did so through investment, diplomacy, and partnership rather than claims of possession. Even as global powers recognized Greenland’s importance, they continued to treat sovereignty as settled rather than negotiable.

The United States, Russia, and China approached the Arctic through different but converging logics. Russia emphasized military modernization and infrastructure along its northern coast, framing the Arctic as a core security frontier. China, lacking Arctic territory, pursued influence through scientific research, investment, and participation in governance forums, presenting itself as a “near-Arctic” stakeholder. The United States focused on maintaining freedom of navigation, alliance cohesion, and technological advantage. Despite divergent strategies, all three operated within the assumption that Arctic competition would be managed rather than territorialized.

This post–Cold War pattern underscored the resilience of postwar norms. Even as rivalry intensified, conquest remained off the table. Greenland’s strategic value increased, yet its political status remained intact. The island continued to function as a site where security interests intersected with legal restraint, Indigenous governance, and alliance politics. Arctic competition after the Cold War thus reaffirmed a central lesson of the modern order: strategic importance does not require ownership. The persistence of this assumption makes contemporary rhetoric about acquisition all the more striking, revealing not continuity with recent practice, but a sharp break from it.

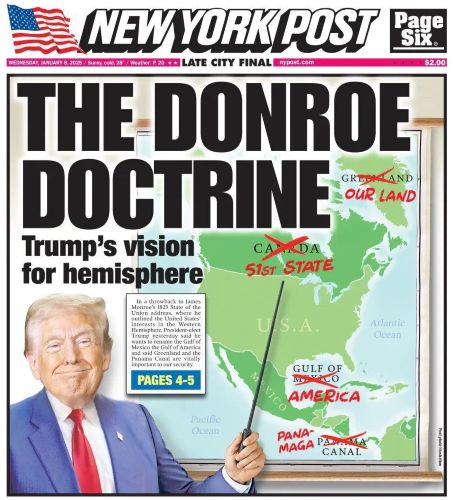

The “Don-roe Doctrine” and the Return of Acquisition Thinking

Against the backdrop of postwar restraint and Arctic cooperation, the reemergence of acquisitionist rhetoric in the late 2010s represented a striking rupture rather than a continuation. When Donald Trump publicly suggested that the United States should purchase Greenland or simply take it, the proposal was widely treated as unserious or eccentric. Yet its significance lay not in feasibility but in logic. The language employed collapsed decades of post-1945 distinction between strategic access and territorial ownership, reviving a nineteenth-century grammar in which land itself was treated as leverage and sovereignty as negotiable.

This rhetoric echoed earlier traditions of American entitlement more closely than modern security practice. The assumption that strategic importance naturally invites acquisition had long been abandoned in favor of basing agreements, alliances, and legal frameworks. By reintroducing the idea of purchase, the “Don-roe Doctrine” implicitly rejected the postwar consensus that conquest and transfer of territory were illegitimate tools of policy. Greenland was framed not as a political community with rights and aspirations, but as an object of transaction whose value lay in geography, resources, and competition with rival powers.

The reaction from Denmark and Greenland underscored how far international norms had shifted since the age of empire. Danish officials rejected the proposal outright, while Greenlandic leaders emphasized that Greenland was not for sale and that decisions about its future rested with its people. These responses reflected the maturation of postcolonial and postwar assumptions about sovereignty and self-determination. What once might have been treated as a pragmatic offer was now widely understood as a violation of political legitimacy, regardless of power asymmetry.

The “Don-roe Doctrine” thus revealed not continuity but dissonance. It exposed the fragility of postwar restraint by demonstrating how easily older acquisition logics could be revived rhetorically, even if they remained politically untenable. More importantly, it highlighted the enduring presence of imperial habits within political imagination, dormant but not extinguished. Greenland’s case illustrates that the rejection of conquest is not irreversible. It must be actively maintained. When security anxiety or great-power rivalry resurfaces, the temptation to convert access into ownership can reappear, challenging the norms that have governed international order for more than seven decades.

Conclusion: Greenland and the Fragility of Postwar Restraint

Greenland’s modern history stands as a sustained counterexample to the older assumption that strategic necessity inevitably leads to territorial possession. From World War II through the Cold War and into the post–Cold War era, the island remained critically important to global security without ever changing hands. Military presence, surveillance infrastructure, and alliance commitments provided access and deterrence, while sovereignty remained intact and increasingly localized. This arrangement was not accidental. It reflected a deliberate post-1945 effort to disentangle power from ownership, replacing conquest with consent as the basis of strategic order.

That settlement proved durable precisely because it was functional. Security objectives were met without destabilizing international law or provoking the legitimacy crises that had accompanied earlier imperial expansions. Greenland illustrates how restraint can coexist with intensity, and how alliances and legal frameworks can manage competition in sensitive regions. The gradual expansion of Greenlandic autonomy further demonstrated that strategic relevance need not suppress political development. On the contrary, security cooperation and self-determination advanced together, reinforcing the legitimacy of the postwar order.

The recent reappearance of acquisitionist rhetoric therefore signals not continuity but vulnerability. It exposes how dependent postwar restraint has been on shared assumptions rather than immutable rules. When those assumptions weaken, older habits of thought can resurface, reframing territory as leverage and sovereignty as negotiable. Greenland’s case shows that even well-established norms require maintenance. They endure not because power has disappeared, but because power has been disciplined by law, alliance, and political expectation.

Ultimately, Greenland matters because it reveals what is at risk. The island’s history demonstrates that strategic competition does not require territorial entitlement, and that security can be pursued without reviving the logic of conquest. The fragility lies not in Greenland’s status, but in the willingness of powerful states to remember why restraint replaced acquisition in the first place. Forgetting that lesson does not merely alter policy. It reopens a historical pathway that the postwar world worked deliberately to close.

Bibliography

- Gad, Finn. History of Greenland, Volume I. Earliest Times to 1700. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1971.

- Gaddis, John Lewis. The Cold War: A New History. New York: Penguin Press, 2005.

- Heidbrink, Ingo. “’ No One Thinks of Greenland:’ S-Greenland Relations and Perceptions of Greenland in the US from the Early Modern Period to the 20th Century.” American Studies in Scandinavia 54:2 (2022): 8-35.

- Heininen, Lassi. Security in the North. Position Paper, NRF Open Meeting, 2004.

- Herring, George C. From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations since 1776. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Humrich, Christoph. The Arctic Council at Twenty: Cooperation between Governments in the Global Arctic. Center for International Relations Research (CIRR) (2015).

- Mazower, Mark. Governing the World: The History of an Idea. New York: Penguin Press, 2012.

- Olsvig, Sara. “Greenland’s Ambiguous Action Space: Testing Internal and External Limitations between US and Danish Arctic Interests.” The Polar Journal 12:2 (2002): 215-239.

- Rosenberg, Emily S. Spreading the American Dream: American Economic and Cultural Expansion, 1890–1945. New York: Hill and Wang, 1982.

- Shadian, Jessica M. The Politics of Arctic Sovereignty: Oil, Ice, and Inuit Governance. London: Routledge, 2014.

- Shaw, Malcolm N. International Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1947.

- Uchoa, Pablo. “The ‘Donroe Doctrine’: Maduro Is the Guinea Pig for Donald Trump’s New World Order.” The Conversation (Jan. 6, 2006): https://theconversation.com/the-donroe-doctrine-maduro-is-the-guinea-pig-for-donald-trumps-new-world-order-272687.

- United Nations. Charter of the United Nations. San Francisco, 1945.

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 1982.

- Westad, Odd Arne. The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of Our Times. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Young, Oran R. Arctic Politics: Conflict and Cooperation in the Circumpolar North. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1992.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.19.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.