To understand the present is not to discover novelty, but to recognize continuity. Today’s digital behavioral engineering is not a break from the past.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Engineered Self

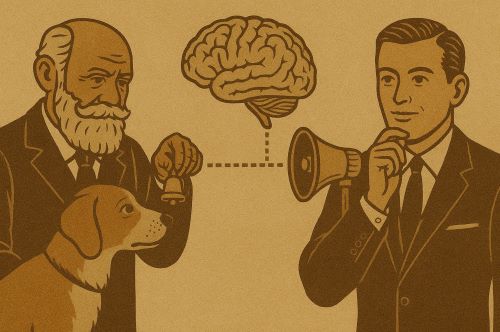

The 20th century did not invent manipulation, but it did mechanize it. Across laboratories, boardrooms, and war rooms, a modern architecture of behavioral control emerged, quietly, incrementally, and with remarkable coherence. What began as laboratory experiments in reflex conditioning became a cultural and commercial project to script desire, perception, and even identity. Pavlov rang his bell, and generations of governments, marketers, and technocrats have been ringing theirs ever since.1

Here I trace the intellectual and industrial lineage of modern behavioral manipulation, moving from early psychological conditioning through the coordinated propaganda of totalitarian regimes, into the corporate boardrooms of mid-century America, and finally into the algorithmic environments of digital capitalism. In each phase, the fundamental goal has remained the same: to understand human motivation well enough to anticipate it and ultimately to command it.

The Conditioning of Reflex: Pavlov, Skinner, and the Scientific Mind

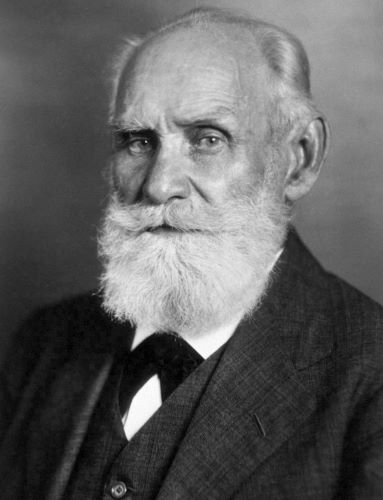

In 1903, Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov presented a paper to the International Medical Congress that would quietly reverberate through the coming century.2 His experiments with dogs and salivation, a seemingly simple demonstration of conditioned response, offered a model of behavior that bypassed cognition entirely. Reflex could be trained. Habits could be installed. The psyche, once the mysterious terrain of soul and self, was rendered instead as circuitry.

The implications were not lost on subsequent scientists. In the United States, John B. Watson would later declare that he could take a dozen infants and shape them into any kind of specialist, “doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief,” given control of their environment.3 B.F. Skinner’s radical behaviorism built a laboratory empire around operant conditioning, replacing reflex with reinforcement but keeping the mechanical core intact. Whether through carrot or stick, behavior could be predicted and shaped.

This was not just science; it was blueprint. Psychology had become an engineering discipline, one that reduced ethics to efficiency and imagined a future of behavioral control so seamless that freedom itself might become obsolete.

Propaganda and the Mass: War, Media, and the Manufacture of Consent

The First World War offered the first grand-scale application of behavioral science to national life. In both Britain and the United States, propaganda offices recruited psychologists, artists, and sociologists to guide public opinion. The Committee on Public Information (CPI), established in 1917 by President Woodrow Wilson, hired figures like Edward Bernays, Freud’s nephew, to craft emotional appeals for enlistment, rationing, and patriotism.4

Bernays would later codify his techniques in Propaganda (1928), a book that begins with the chilling declaration: “The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society.”5 Though he used the term “propaganda” unselfconsciously, his approach was not coercive in the traditional sense. It was soft power wielded with surgical precision, manipulation disguised as education, coercion disguised as choice.

Totalitarian regimes elevated this method to brutal perfection. Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda, studied both Bernays and the CPI.6 The Nazi state, like the Soviet Union, understood that power over perception was as critical as control of the police. Propaganda posters, radio broadcasts, film reels, and staged spectacles did not simply inform citizens; they constructed reality itself.

Selling the Self: Consumer Capitalism and the Emotional Economy

After World War II, the techniques of mass persuasion were naturalized within a booming consumer economy. Madison Avenue ad men, many of whom had worked in wartime propaganda, now sold soap, cars, and cigarettes using the same psychological playbook.7 Market research departments employed Freudian analysts to uncover consumers’ unconscious associations. Advertisements appealed not to rational need but to desire, insecurity, and identity. You were not buying a product; you were buying who you wanted to be.

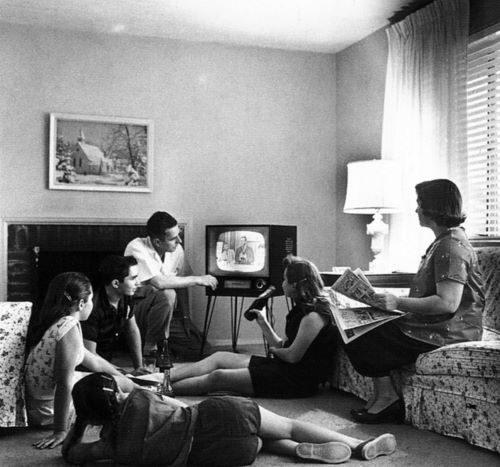

The rise of television accelerated this shift. By the 1950s, American households were inundated with images of domestic bliss, sexual allure, and rugged masculinity, all framed as purchasable ideals.8 The boundaries between culture and commerce blurred, then collapsed. Brands became moral signifiers. Corporations began to manage not only their products but their social meanings.

This was not accidental. As historian Lizabeth Cohen has shown, postwar corporate strategy involved a deliberate effort to create what she termed the “Consumer’s Republic,” where civic participation was increasingly measured by purchasing power.9 The citizen-consumer hybrid was not merely born; it was manufactured.

Surveillance and Prediction: The Emergence of the Algorithmic Subject

By the late 20th century, a new model of control was emerging, shaped less by broadcast persuasion and more by data collection. Behavioral psychology had taught corporations how to appeal to the unconscious. The computer revolution offered something more: the ability to track it in real time.

The rise of the internet, and particularly of social media, introduced a paradigm of behavioral capture that rendered individuals legible at a level previously unthinkable. Search queries, click patterns, location data, and facial expressions were no longer ephemeral; they became capital.10 Companies like Google and Facebook, while ostensibly platforms for connection and information, operated as massive behavioral laboratories. Their users were not merely customers but subjects of continuous experimentation.

The most powerful expression of this model came in what Shoshana Zuboff termed “surveillance capitalism,” a system in which user behavior is mined, modeled, and monetized to predict future actions.11 Algorithms do not persuade in the traditional sense. They do not appeal. They shape the environment. They nudge.

Unlike mid-century advertisements, algorithmic manipulation is often imperceptible. It comes not in the form of slogans or imagery, but in the structure of the interface itself, the order of a feed, the placement of a button, the timing of a notification. The user is not asked. He is guided. Or, more precisely, he is programmed.

Conclusion: The Myth of a New Problem

What is often framed as a crisis of the digital age, the erosion of free will, the rise of echo chambers, the behavioral steering of entire populations, is in fact the latest expression of a century-long project. The tools have changed. The ambitions have not.

From Pavlov’s bell to Facebook’s algorithm, the thread remains taut: to turn the human being into something readable, predictable, and therefore controllable. This is not simply a technological story, nor is it merely psychological. It is a historical arc, shaped by war, commerce, ideology, and power.

To understand the present is not to discover novelty, but to recognize continuity. Today’s digital behavioral engineering is not a break from the past. It is its fulfillment.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Ivan P. Pavlov, Conditioned Reflexes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1927), 13.

- Daniel P. Todes, Ivan Pavlov: A Russian Life in Science (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 410.

- John B. Watson, Behaviorism (New York: W.W. Norton, 1925), 82.

- George Creel, How We Advertised America (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1920), 15–20.

- Edward Bernays, Propaganda (New York: Horace Liveright, 1928), 1.

- Peter Longerich, Goebbels: A Biography (New York: Random House, 2015), 108–109.

- Stuart Ewen, Captains of Consciousness: Advertising and the Social Roots of the Consumer Culture (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1976), 144–155.

- Lynn Spigel, Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 45–49.

- Lizabeth Cohen, A Consumers’ Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America (New York: Knopf, 2003), 120–128.

- Frank Pasquale, The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms That Control Money and Information (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015), 58–64.

- Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism (New York: PublicAffairs, 2019), 93–104.

Bibliography

- Bernays, Edward. Propaganda. New York: Horace Liveright, 1928.

- Cohen, Lizabeth. A Consumers’ Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America. New York: Knopf, 2003.

- Creel, George. How We Advertised America. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1920.

- Ewen, Stuart. Captains of Consciousness: Advertising and the Social Roots of the Consumer Culture. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1976.

- Longerich, Peter. Goebbels: A Biography. New York: Random House, 2015.

- Pasquale, Frank. The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms That Control Money and Information. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015.

- Pavlov, Ivan P. Conditioned Reflexes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1927.

- Skinner, B.F. Science and Human Behavior. New York: Macmillan, 1953.

- Spigel, Lynn. Make Room for TV: Television and the Family Ideal in Postwar America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

- Todes, Daniel P. Ivan Pavlov: A Russian Life in Science. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Watson, John B. Behaviorism. New York: W.W. Norton, 1925.

Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. New York: PublicAffairs, 2019.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.16.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.