The Venezuelan experience between 1858 and 1863 exposes the fragile boundary between reform and rupture in post-independence societies marked by deep inequality.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: A Revolution without Blood, a War without Restraint

In March 1858, Venezuela experienced a political rupture that appeared, at least on the surface, to defy the violent patterns that had marked much of its post-independence history. The removal of President José Tadeo Monagas and the collapse of the Conservative regime occurred with remarkably little bloodshed. Political power shifted through negotiation, elite defection, and institutional maneuvering rather than mass violence. Contemporary observers and later historians alike have often treated the March Revolution as a rare moment of restraint in a political culture long accustomed to force. Yet this apparent success would prove tragically fleeting.

Within a year, Venezuela descended into the Federal War, a sprawling civil conflict that lasted from 1859 to 1863 and claimed tens of thousands of lives. Unlike the orderly transfer of power in 1858, the Federal War unfolded as a decentralized, brutal struggle characterized by regional militias, irregular warfare, and widespread civilian suffering. Villages were destroyed, agricultural production collapsed, and political authority fragmented across competing caudillos. The contrast between the bloodless revolution and the bloody war that followed presents a historical paradox that demands explanation.

What follows argues that the March Revolution did not fail because it was peaceful, but because it was incomplete. It represented a reconfiguration of elite power rather than a transformation of social relations. By removing Monagas without addressing the structural inequalities that defined Venezuelan society, the revolution created expectations it could not fulfill. Federalism, decentralization, and popular sovereignty were invoked rhetorically, but land distribution, rural exclusion, and regional marginalization remained largely intact. Peaceful political change, in this context, functioned as a temporary suspension of conflict rather than its resolution.

The Federal War should therefore be understood not as an abrupt departure from the revolution of 1858, but as its violent aftermath. The bloodshed of the early 1860s exposed the limits of reform conducted from above in a society fractured by deep economic and regional divides. By examining the relationship between the March Revolution and the Federal War, I situate Venezuela’s mid-nineteenth-century crisis within broader patterns of post-independence instability in Latin America, where the promise of republican reform repeatedly collided with the realities of social inequality and contested sovereignty.

The Conservative Order Before 1858: Centralization, Exclusion, and Rural Marginality

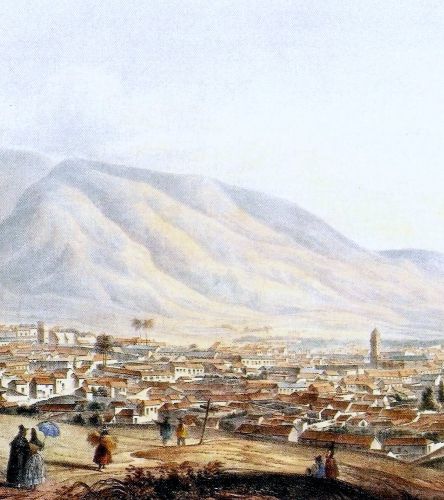

In the decades following independence, Venezuela struggled to construct a stable political order capable of reconciling republican ideals with deeply unequal social realities. By the mid-nineteenth century, power had consolidated around a conservative political elite centered in Caracas, drawing legitimacy from constitutional forms while relying heavily on informal networks of patronage and coercion. The presidency of José Tadeo Monagas represented the culmination of this order. Although Monagas initially aligned himself with liberal reformers, his rule increasingly relied on centralized authority, personal loyalty, and the marginalization of dissent. Stability was achieved not through broad inclusion, but through containment.

This conservative system rested on a narrow conception of citizenship. Political participation remained effectively restricted to urban elites, military officers, and landholding classes, while the vast rural population was excluded from meaningful representation. Voting rights were limited, literacy requirements excluded most peasants, and regional voices were filtered through local strongmen rather than institutional channels. The republic thus functioned less as a participatory polity than as a negotiated settlement among elites, one that preserved order while suppressing demands for structural change.

Centralization further deepened these divisions. Caracas emerged as the administrative and political axis of the nation, absorbing decision-making authority and fiscal control at the expense of provincial autonomy. Regional grievances accumulated as local communities found themselves governed by distant institutions that neither reflected their interests nor addressed their needs. Federalism, long discussed as a potential remedy, remained largely theoretical. In practice, centralization reinforced existing hierarchies while limiting the capacity of rural regions to influence national policy.

Rural marginality was not merely political, but economic and social as well. Land ownership remained highly concentrated, and access to productive resources was uneven. Smallholders, former soldiers of the independence wars, and llanero communities faced chronic insecurity, compounded by debt peonage and the absence of meaningful land reform. Independence had promised mobility and opportunity, but decades later those promises rang hollow for much of the countryside. This disjunction between republican rhetoric and lived reality produced a reservoir of resentment that conservative governance neither alleviated nor fully suppressed.

The conservative order before 1858 thus maintained stability by postponing confrontation rather than resolving it. Its reliance on centralized authority and elite consensus created an appearance of control, but at the cost of legitimacy among large segments of the population. Political exclusion and rural marginalization did not disappear under Monagas. They hardened. When the conservative coalition fractured in 1858, the institutions it left behind proved incapable of containing the forces it had long ignored. The apparent calm of the pre-revolutionary period was therefore deceptive, masking the social pressures that would soon erupt with devastating force.

The March Revolution of 1858: Elite Consensus and the Illusion of Stability

The March Revolution of 1858 unfolded less as a popular uprising than as a carefully managed political rupture among Venezuela’s governing elites. The collapse of José Tadeo Monagas’s regime was precipitated not by mass mobilization, but by the withdrawal of support from factions within the military, the political class, and segments of the conservative establishment itself. What distinguished this moment from earlier coups and rebellions was its restraint. Power shifted with minimal bloodshed, signaling an apparent exhaustion with violence among those who had long monopolized authority.

Central to this transition was the formation of a broad, if fragile, coalition that united disaffected conservatives with liberal reformers. Their shared objective was not radical transformation, but the restoration of constitutional order and the removal of a presidency increasingly viewed as personalist and illegitimate. The elevation of Julián Castro to the presidency symbolized compromise rather than rupture. Castro was acceptable precisely because he appeared capable of stabilizing the system without fundamentally altering its social foundations. In this sense, the revolution functioned as a reset of elite consensus rather than a challenge to the structures that had sustained conservative rule.

The bloodless character of the revolution reinforced the belief that Venezuela had entered a new political phase. Contemporary observers interpreted the peaceful transfer of power as evidence that republican institutions had matured and that the cycle of civil war might finally be broken. This optimism, however, rested on a narrow understanding of stability. Order was measured by the absence of immediate violence at the center, not by conditions in the countryside or by the depth of popular inclusion. The revolution’s success was thus defined procedurally rather than socially.

Beneath this surface of calm, the limitations of elite reform were already evident. The March Revolution produced changes in leadership and rhetoric, but it left intact the underlying patterns of land concentration, regional inequality, and rural exclusion. Liberal language flourished in speeches and proclamations, yet concrete measures addressing the grievances of peasants and provincial communities lagged or failed to materialize altogether. The revolution’s reliance on negotiation among elites ensured short-term peace while deferring the harder questions of redistribution and representation.

The illusion of stability created in 1858 proved dangerously persuasive. By mistaking elite agreement for national reconciliation, the post-revolutionary government underestimated the volatility of a society long shaped by exclusion and unmet promises. The March Revolution demonstrated that political change without violence was possible, but it also revealed how limited such change could be when confined to the upper tiers of power. The calm it produced was real, but shallow. Once the consensus that sustained it fractured, the forces it had temporarily contained would reemerge with far greater intensity.

Liberalism without Land: The Unfulfilled Promises of Reform

The political language that followed the March Revolution of 1858 was saturated with liberal ideals. Federalism, decentralization, and popular sovereignty dominated speeches, proclamations, and constitutional debates. Reformers portrayed the revolution as a moral and political rebirth, one that would finally align Venezuela’s republican institutions with the aspirations of its people. Yet this liberal vocabulary operated largely at the level of principle rather than policy. The promise of reform proved far easier to articulate than to implement, particularly when doing so threatened entrenched interests.

At the heart of this failure lay the unresolved question of land. For rural Venezuelans, liberalism carried concrete expectations: access to land, relief from debt peonage, and protection from arbitrary authority. Independence had raised similar hopes decades earlier, only to leave patterns of land concentration largely intact. After 1858, reformist leaders again spoke the language of equality while leaving the agrarian structure untouched. Estates remained consolidated in elite hands, and smallholders continued to exist in precarious legal and economic positions. Liberalism, divorced from land reform, offered symbolism without substance.

This disconnect was not accidental. Many liberal leaders emerged from the same social strata that had benefited from conservative rule. While they opposed personalist governance and centralization, they were far less willing to disrupt property relations that underpinned their own power. As John V. Lombardi has observed in his broader analysis of Venezuelan political culture, reform movements often sought to expand political participation without redistributing economic resources. The result was a reformism that appeared progressive in theory while remaining conservative in practice.

The consequences of this contradiction were profound. Liberal rhetoric raised expectations among rural populations already burdened by inequality and exclusion. Federalism was interpreted not merely as administrative decentralization but as a promise of local autonomy and material improvement. When these expectations went unmet, frustration hardened into radicalization. Liberalism ceased to function as a moderating ideology and instead became a language through which deeper grievances were articulated and justified.

Economic conditions further exacerbated these tensions. Venezuela’s post-independence economy remained fragile, dependent on agriculture and vulnerable to disruption. Rural communities bore the brunt of instability, facing declining productivity and limited access to credit. The absence of meaningful reform left these populations exposed, while political debates in Caracas focused increasingly on constitutional design rather than social relief. The gap between national discourse and local reality widened steadily in the months following the revolution.

By late 1858, it had become clear that liberal reform, as practiced, could not contain the pressures it had unleashed. The failure to translate ideology into tangible change transformed liberalism from a unifying project into a source of division. Promises made but not fulfilled undermined confidence in peaceful political processes and lent credibility to more radical solutions. In this sense, the Federal War did not erupt despite liberal reform, but in part because of it. Liberalism without land reform proved incapable of sustaining peace in a society where inequality remained both visible and deeply felt.

The Federal War Begins: From Political Crisis to Social Explosion (1859)

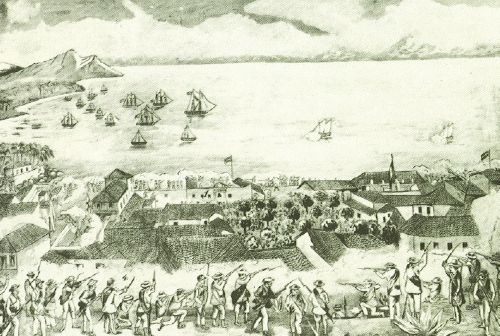

The outbreak of the Federal War in 1859 marked the collapse of the fragile political equilibrium established by the March Revolution. What had begun as an elite dispute over constitutional order rapidly transformed into a broad social conflict that engulfed much of the Venezuelan countryside. The removal of Monagas and the installation of a provisional government failed to stabilize the nation because the underlying causes of unrest were never neutralized. As political authority weakened at the center, long-suppressed grievances found expression through violence. The war did not erupt suddenly; it unfolded as pressure finally released.

The immediate political crisis was rooted in the inability of the post-revolutionary government to reconcile competing visions of the state. Federalism, loosely defined and inconsistently pursued, became a rallying cry rather than a coherent program. Conservative forces feared the erosion of centralized authority, while radical liberals viewed delay as betrayal. The resulting paralysis fractured the ruling coalition and eroded confidence in institutional solutions. When compromise collapsed, armed resistance emerged as a credible alternative for those who had little to lose.

The social composition of the early federalist movement reveals the deeper character of the conflict. Rural peasants, former soldiers, displaced laborers, and marginalized llaneros formed the backbone of federalist forces. For these groups, the war was not primarily about constitutional arrangements but about land, autonomy, and survival. Political slogans provided legitimacy, but material grievances supplied motivation. Violence became a means of asserting claims long ignored by legal and political systems.

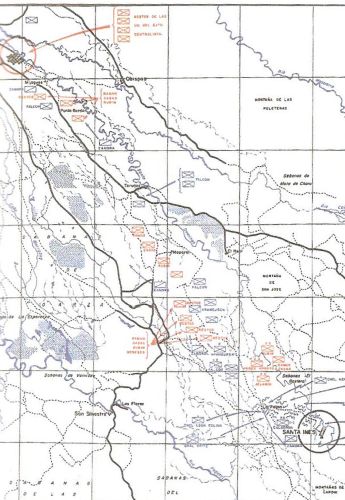

The decentralized nature of the war reflected both its popular origins and the weakness of national authority. Rather than a single unified rebellion, the Federal War emerged as a constellation of regional uprisings, each shaped by local conditions and leadership. Caudillos mobilized followers through personal loyalty, promises of redistribution, and appeals to federalist ideology. This fragmentation made the conflict exceptionally difficult to contain, as no single defeat or negotiation could bring it to an end.

Violence during the early stages of the war was intense and often indiscriminate. Villages were attacked, property destroyed, and civilians drawn into cycles of retaliation. The absence of clear front lines blurred the distinction between combatant and non-combatant, amplifying the war’s social toll. Unlike earlier elite conflicts, the Federal War penetrated deeply into everyday life, transforming political struggle into a sustained humanitarian crisis. The scale of destruction reflected not only military confrontation but the breakdown of social restraint.

By mid-1859, it was evident that Venezuela had entered a new phase of conflict. The Federal War represented a qualitative shift from political instability to social explosion. What peaceful reform could not achieve, violence now sought to impose. The bloodshed that followed exposed the failure of the March Revolution to resolve foundational inequalities and demonstrated the limits of elite-led change. The war was not an aberration imposed from below, but the culmination of tensions that reform had raised without resolving.

Violence, Fragmentation, and the Limits of Federalism (1859–1863)

As the Federal War intensified, its defining characteristic became fragmentation rather than coordination. Despite the shared language of federalism, the conflict lacked a unified command structure or coherent national strategy. Federalist forces operated largely as regional militias, shaped by local grievances, personal loyalties, and opportunistic leadership. This decentralization reflected both the appeal and the weakness of federalist ideology. While it mobilized broad support, it failed to produce the institutional cohesion necessary to translate rebellion into stable governance.

The conduct of the war revealed the profound limits of federalism as a practical political framework. Federalist leaders invoked decentralization and local autonomy, yet the absence of administrative capacity meant that authority often collapsed entirely rather than devolving constructively. In many regions, power passed from the central state not to representative local institutions but to armed caudillos whose legitimacy rested on force. Germán Carrera Damas argued in his broader reflections on Venezuelan nationhood that political fragmentation in such contexts often substitutes personal rule for institutional development.

Violence became both instrument and outcome of this fragmentation. Without centralized control or clear norms of engagement, the war degenerated into cycles of reprisal that devastated civilian populations. Raids on villages, forced requisitions, and the destruction of crops were common, eroding the economic foundations of rural life. Civilians were not incidental victims but central targets, as control over territory depended on disrupting the social networks that sustained opposing forces. The war thus blurred any remaining boundary between political struggle and social collapse.

The scale of destruction further undermined the federalist cause. Agricultural production declined sharply, trade routes deteriorated, and entire regions were depopulated. Hunger and disease accompanied violence, compounding the human cost. What had begun as a movement promising autonomy and justice increasingly resembled a prolonged catastrophe. Federalism, once imagined as a remedy for centralization, appeared incapable of restoring order or alleviating suffering under wartime conditions.

Leadership divisions deepened these problems. Competing federalist commanders pursued divergent objectives, negotiating truces or launching offensives based on local advantage rather than national strategy. Efforts to impose discipline or unify command were sporadic and largely unsuccessful. This internal disunity weakened federalist leverage in negotiations and prolonged the conflict, as no single authority could credibly speak for the movement as a whole.

The central government, meanwhile, proved equally incapable of restoring control. Successive administrations struggled to project authority beyond Caracas, relying on exhausted troops and unstable alliances. Attempts to suppress the rebellion militarily often exacerbated violence, reinforcing cycles of retaliation rather than establishing peace. The state’s inability to monopolize force underscored the depth of institutional decay exposed by the war.

By the early 1860s, the Federal War had exhausted both its combatants and the society that sustained them. Federalism had mobilized resistance but failed to generate a viable alternative order. The war’s fragmentation revealed that decentralization without institutional capacity leads not to autonomy but to disintegration. The conflict thus demonstrated the tragic paradox at the heart of Venezuelan federalism: a doctrine intended to empower local communities instead accelerated their destruction when severed from the structures necessary to govern peacefully.

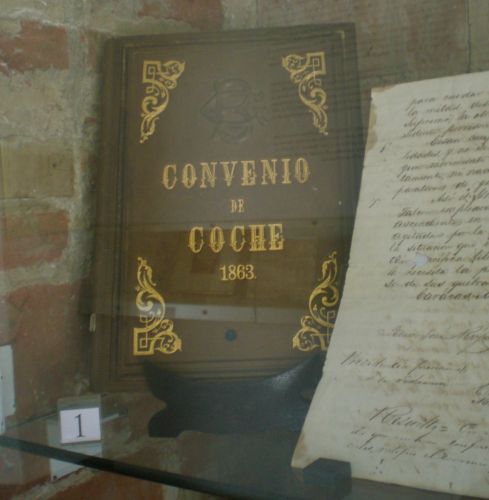

The Treaty of Coche and the Hollow Peace of 1863

The signing of the Treaty of Coche in 1863 formally ended the Federal War, but it did not resolve the contradictions that had produced it. After four years of devastation, exhaustion rather than reconciliation drove both sides toward settlement. The treaty institutionalized federalism and brought federalist leaders into power, marking a symbolic victory for the rebellion. Yet the agreement emerged from mutual depletion, not consensus. Peace arrived because continued war had become unsustainable, not because its underlying causes had been addressed.

In political terms, the treaty represented a transfer of authority rather than a reconstruction of the state. Federalism was enshrined constitutionally, but the institutional capacity required to make it effective remained weak. Provinces gained nominal autonomy, yet local governance continued to depend heavily on personal authority and military influence. The decentralization promised by the treaty often translated into fragmented power rather than participatory administration. The state survived, but it remained fragile and unevenly rooted across the national territory.

Socially, the peace was deeply incomplete. The war had devastated rural communities, destroyed agricultural production, and displaced large segments of the population. Little effort was made to repair these losses or to integrate former combatants into stable economic life. Land distribution remained largely unchanged, and the grievances that had fueled popular participation in the war were left unresolved. For many rural Venezuelans, the end of fighting did not bring security or opportunity, but merely a different configuration of authority.

The treaty also entrenched a pattern that would recur throughout Venezuelan history: the resolution of conflict through elite negotiation after mass suffering. Federalist leaders who emerged victorious inherited a society fractured by violence and scarcity, yet the political settlement prioritized stability over transformation. John V. Lombardi noted in his assessment of postwar Venezuela that the new federal order absorbed revolutionary leaders into government without dismantling the social hierarchies that had made revolution appealing in the first place. Peace consolidated power, but it did not democratize it.

The hollow nature of the peace forged at Coche underscores the central argument of this essay. The Federal War ended not with the fulfillment of its promises, but with their postponement. Federalism survived as an ideal and a constitutional principle, but it failed to resolve the tensions between center and periphery, elite and popular classes, that had driven the conflict. The Treaty of Coche closed a chapter of open warfare, yet it left intact the structural conditions that would continue to shape Venezuelan political life long after the guns fell silent.

Conclusion: When Peaceful Revolution Fails

The Venezuelan experience between 1858 and 1863 exposes the fragile boundary between reform and rupture in post-independence societies marked by deep inequality. The March Revolution demonstrated that political change without bloodshed was possible, even in a nation long shaped by caudillo warfare and institutional fragility. Yet the very restraint that made the revolution remarkable also revealed its limitations. By confining change to the sphere of elite negotiation, the revolution postponed confrontation with the social and economic realities that most Venezuelans continued to endure.

The descent into the Federal War illustrates how unfulfilled reform can radicalize expectation rather than contain it. Liberalism promised inclusion, autonomy, and justice, but delivered few tangible improvements to those whose support it implicitly solicited. Federalism became a vessel into which popular grievances were poured, transforming a constitutional doctrine into a social insurgency. Violence did not arise from ideological excess alone, but from the widening gap between political rhetoric and lived experience. When peaceful mechanisms failed to redistribute power or resources, war became a means of articulation.

The Treaty of Coche brought an end to organized fighting, but not to the structural conditions that had fueled the conflict. Federalism survived as a constitutional form, yet its implementation rested on weak institutions and enduring hierarchies. The postwar settlement absorbed revolutionary leaders into the state without fundamentally altering the relationships between land, labor, and authority. Peace restored order, but it did so by stabilizing inequality rather than dismantling it. The war’s resolution thus mirrored the revolution that preceded it: procedurally successful, socially incomplete.

The broader lesson of Venezuela’s mid-nineteenth-century crisis lies in the limits of reform conducted without transformation. Peaceful revolution can interrupt violence, but it cannot substitute for structural change where inequality is entrenched and exclusion widespread. The Federal War was not a repudiation of the March Revolution, but its reckoning. Together, they reveal how societies emerging from colonial rule struggled to reconcile republican ideals with social realities, and how the failure to do so repeatedly converted hope into catastrophe.

Bibliography

- Arcila Farías, Eduardo. Economía colonial de venezolana. Caracas: Universidad Central de Venezuela, 1946.

- Bethell, Leslie, ed. The Cambridge History of Latin America, Volume III: From Independence to c. 1870. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

- Brewer-Carias, Allan R. “Centralized Federalism in Venezuela.” Duquesne Law Review 49, no. 9 (2005): 629-643.

- Carrera Damas, Germán. El culto a Bolívar. Caracas: Universidad Central de Venezuela, 1989.

- González, Manuel Vicente. Historia contemporánea de Venezuela. Caracas: Tipografía Americana, 1889.

- Halperín Donghi, Tulio. The Contemporary History of Latin America. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1967.

- Lombardi, John V. People and Places in Colonial Venezuela. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1976.

- —-. Venezuela: The Search for Order, the Dream of Progress. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982.

- Loy, Jane M. “Horsemen of the Tropics: A Comparative View of the Llaneros in the History of Venezuela and Colombia.” Boletín Americanista 31 (1981): 159-171.

- Lynch, John. Caudillos in Spanish America, 1800–1850. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992.

- McBeth, Brian S. Dictatorship and Politics in Venezuela, 1810–2013. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008.

- Ramos Pérez, Demetrio. Estudios de historia venezolana. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1976.

- Rippy, J. Fred. Historical Evolution of Hispanic America. New York: Prentice-Hall, 1932.

- Skidmore, Thomas E., and Peter H. Smith. Modern Latin America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Vallenilla Lanz, Laureano. Cesarismo democrático. Caracas: Editorial Nacional, 1919.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.05.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.