The American Revolution was not primarily about democracy, at least understood as a form of government.

By Dr. Christopher Hobson

Visiting Research Fellow

United Nations University

Introduction

A great revolution has happened – a revolution made, not by chopping and changing of power in any of the existing states, but by the appearance of a new state, of a new species, in a new part of the globe. It has made as great a change in all the relations, and balances, and gravitation of power, as the appearance of a new planet would in the system of the solar world.

Edmund Burke (1782) (quoted in Armitage 2007: 87)

The People are the King.

Gouverneur Morris (quoted in Madison 1787)

The founding of the United States may seem a somewhat paradoxical place to begin this history. On the one hand, it certainly appears as an obvious starting point, considering the central role the country played in the subsequent rise of democracy in international politics, what Azar Gat terms the ‘United States factor’ (Gat 2009: 6–8). Scholars such as Daniel Deudney, Michael McFaul and Tony Smith have strong grounds to suggest that no country has played a more significant part in the defence and spread of democracy (Cox et al. 2000; Deudney 2007; Kagan 2015; McFaul 2004; T. Smith 1994). The close relationship between the United States and democracy thus encourages one to revisit its founding. On the other hand, if one does return to this point in time, an awkward fact soon appears: the American Revolution was not primarily about democracy, at least understood as a form of government. Democracy was little thought about or discussed during colonial times, and this never changed sufficiently for it to become central to political discourse during the revolution (Kenyon 1962: 158; Lokken 1959: 570–1).

That the United States, a country which now associates itself and its legacy so strongly with democracy, actively denied this label just over 200 years ago offers a stark reminder of how recently the concept has come to signify something positive. Through an examination of the way democracy was understood in the founding period, the historical layers of meaning which shaped the concept can be identified, as can its stubbornly classical nature. While the revolutionaries steadfastly maintained a sceptical view of democracy as a form of government, popular sovereignty was widely extolled. Indeed, one finds what may now seem like a rather odd arrangement: the attempt to found a polity on popular sovereignty and institute a government that was answerable to the people, but at the same time, consistently refusing to identify it as a democracy. Rather, the revolutionaries saw themselves as constructing a republic. In this regard, democracy may not have been a pivotal concept in revolutionary discourse, but republicanism certainly was (Bailyn 1967; Pocock 1975; Wood 1969). During the founding of the United States the relationship between these concepts was complex, for they were used by some as synonyms and by others as antonyms. What linked democracy and republicanism was the overarching notion of popular sovereignty. For the founding fathers what separated the two, and created the possibility for a state based on the people without it being a democracy, was the principle of representation. Representation offered a way of mediating between the people as the constitutive power (popular sovereignty) and the people as the constituted power in the form of the executive and legislature (democratic government). The consequences of these developments would ultimately reach well beyond the United States, with the advancement of popular sovereignty during the revolution representing the beginning of the shift from international legitimacy being exclusively monarchical (Bukovansky 2002).

A Pre-History of Democracy in Revolutionary America

The American Revolution did not commence with the aim of independence: it initially started as a protest against colonial misrule, with taxation being the main source of discontent. American complaints stemmed from a belief that the British constitution had been corrupted by the king and his ministers. At the time, discourse was structured more in terms of the distinction between free and arbitrary government, than the specific principles it should follow or the kind of institutions it should have (Stourzh 1970: 40–2). Democracy was not considered extensively. ‘There was no controversy over the meaning of the term “democracy” in colonial America,’ as Roy Lokken explains, ‘the colonists gave little thought to it, and the word seldom appeared in their political writings, speeches, sermons, public papers, and private correspondence’ (Lokken 1959: 570).

This widespread lack of interest in democracy stemmed from a number of factors. First, the mixed constitution was still held in high esteem. The problem was identified as the corruption that had come to define British rule, rather than the form of constitution per se. In contrast, democracy was generally understood as an unmixed form, some-thing that had been strongly warned against by theory and history. Second, the limited amount of serious discussion about the possibility of independence ruled out extensive considerations of any form of government, democracy or otherwise. Third, democracy remained a somewhat antiquarian term, with its meaning strongly shaped by the classics. Each generation of thinkers had largely accepted the received wisdom handed down from the ancients that democracy was a danger-ous and unstable form of rule.1

Given the strong influence of classical interpretations in shaping democracy’s meaning during and after the revolution, it is necessary to reflect on them in more detail. As James Farr notes, the pre- history of any concept is an essential component for constructing a larger conceptual history (Farr 1989: 38). Democracy’s origins were seen as lying in Athens and the other city- states of ancient Greece. Well into the nineteenth century Athens remained ‘the immediate antecedent and model of modern democracy’ (Canfora 2006: 47). Of primary significance were not the actual democratic practices of ancient Greece, but how they had been recounted and interpreted historically, something that had been done mostly by democracy’s enemies (J. Roberts 1994; Keane 2009). Democracy was a direct form of rule, as indicated in the etymology of demokratia: the people (demos) ruled, they held and exercised power (kratos). That the people were both the source and direct executors of power endowed democracy with connotations of anarchy, instability and mobbishness, which were at the heart of how the concept was understood in revolutionary America.

The direct nature of democracy in Athens – the demos exercising kratos – was fundamental to how the concept was historically interpreted. While Athenian democracy may have included some forms of representation, it was neither theorised nor interpreted as a defining characteristic, and it is an essentially modern trait (Manin 1996; Pitkin 1967). Representation became relevant only once the size of the polity grew, and democracy was disaggregated into a form of state and a form of government. The directness of the Athenian system meant that for the people to be able to assemble and deliberate the polis had to be small. Moreover, a certain level of equality among its members was needed. The implications of these perceived requirements were significant. Regardless of whether or not democracy was considered desirable, these practical requirements seemed to render it impossible for modern states far greater in territory and population.

The direct nature of democracy generally precluded such practical questions, however, as putting power in the hands of the people was seen as particularly ill advised in the first place. There were two primary concerns. First, from an eighteenth- century perspective, there was no separation of powers. The executive, legislative and judicial powers were all held by the same people. This was seen as a recipe for tyranny, if not complete disaster. The directness of democracy meant it was susceptible to the whims of the erratic demos, and liable to fall under the sway of ruthless and power-hungry demagogues, such as Cleon in Athens. This was connected to a greater problem, whereby power was invested in those least capable of exercising it properly. Instead of the philosopher-kings Plato hoped for, or the enlightened leadership Pericles represented for Thucydides, it was the unstable, passionate, self-interested demos that ruled in a democracy. These concerns crystallised around the fear of mob rule, which was central to the way democracy was historically interpreted. The conclusion handed down from ancient Greece was that the direct exercise of power by the demos was necessarily mistaken. Reflecting this perception, James Madison proposed that, ‘had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob’ (Madison 2001: 288).

The concern over democracy’s perceived tendency to degenerate into mob rule stemmed, in part, from it being understood as a social form of rule. In this understanding, the demos were not the whole political community but one specific grouping: the poor multitude. In the influential works of Plato and Aristotle democracy was identified as a form of government where the poor many rule over the privileged few. Plato’s Socrates stated that ‘democracy comes into being after the poor have conquered their opponents, slaughtering some and banishing some, while to the remainder they give an equal share of freedom and power’ (Plato 1901: 267). Aristotle was less dramatic but formulated a similar understanding:

‘A democracy is a state where the freemen and the poor, being in the majority, are invested with the power of the state’ (Aristotle 2006: 87).

The equality that democracy was seen to require furnished it with a dangerous levelling instinct, making it a threat to landed and propertied interests. This further challenged its relevance for modern states, especially in the incipiently liberal America.

Contemporary understandings of democracy were also shaped by the highly influential ‘numerical’ approach of Aristotle, which identified six forms of governance for the polis: three virtuous and three corrupted, each triad comprising rule by one individual, rule by the few and rule by the many.2 What separated the virtuous forms of rule from the corrupted was whose interests the rulers ruled in: those of the polisor their own. Democracy was identified as a perverted form of rule because it ruled in the interests of one class, the poor. This ‘numerical’ approach was later replicated and renovated by a host of classical and medieval thinkers. It is here that one can identify the roots of a second meaning of democracy prevalent during the American Revolution, in which it was understood as part of a mixed regime. Underpinning the logic of the mixed constitution was the notion that each form of rule was susceptible to a certain kind of corruption. Unmixed regimes were seen as trapped in a cyclical process in which each virtuous form eventually mutated into its unvirtuous alter-ego, before in turn being replaced by the next virtuous form of rule. This interpretation was particularly prominent in the histories of Polybius, which were widely read and cited during this period. Polybius proposed that the solution to this revolutionary cycle could be found in Rome, which he suggested had a mixed constitution composed of the one, the few and the many, thereby balancing the dangers posed by each in their simple forms. In this system, democracy was a necessary part of the mix, but it had a very limited role. The idea of a mixed constitution would later famously be found at the heart of Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws, which was highly influential in late eighteenth-century America, especially during the creation and ratification of the constitution (Carpenter 1928). In this tradition, the unmixed form of democracy was seen as complete folly, but when carefully balanced and given a limited role, it took on a more positive meaning.

Democracy was thus understood in two main ways during the colonial and early revolutionary periods. First, there was the simple, unmixed variant most commonly associated with Athens, which was dismissed as an antiquated form of rule inapplicable to and unadvisable for the modern world. The second conception of democracy also had classical roots, but was more immediately connected with the famed British mixed constitution. Democracy was regarded in social terms, in which it represented one social order, which was then combined with aristocratic and monarchic branches of government to create a mixed constitution, thereby protecting against the forms of corruption each branch suffered by itself. In its unmixed form, democracy was almost uniformly condemned, but when forming part of a mixed constitution it was seen as having a more positive role, on the proviso that it was carefully checked and limited. As America moved towards independence, questions related to sovereignty and forms of rule became more prominent.

From Revolt to Revolution

From 1774 to 1776 independence increasingly came to be seen as the only solution to the perceived misrule and corruption emanating from Great Britain. In turn, discourse shifted from the distinction between free and arbitrary rule to a more detailed consideration of forms of government and the foundations of sovereignty (Stourzh 1970: 40–43). The republican tradition of thought was particularly influential, quickly assuming a prominent role in the self- identification of the revolution-aries. In this regard, Cecelia Kenyon suggests that

before 1776, the prevailing opinion in America had been that the ends of government . . . could be secured within the framework of monarchy. . . . After 1776, they tended to associate all the characteristics of good government with republicanism, and with republicanism only. (Kenyon 1962: 165)

Due to its centrality in eighteenth-century political discourse, republicanism had multiple and contested meanings, but on a basic level it was connected with popular sovereignty, and operated as a counter- concept to monarchy.

Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, published at the start of 1776, would be central as both a catalyst and a symbol of America’s movement towards independence and its adoption of republicanism. It perfectly captured the moment, helping to forge the opinion that breaking with Britain was necessary. Common Sense was essentially a demolition job, an anti-monarchical polemic that forcefully expounded the need for independence. By arguing that British outrages prevented the possibility of reconciliation, he sought to locate responsibility for America moving towards independence with the British, and specifically their king. In making his case, Paine argued that remaining under the sway of a monarchy would drag America into the perpetual wars that plagued Europe. ‘It is the true interest of America to steer clear of European contentions, which she never can do, while [dependent] on Britain.’ Paine stressed the need for America to separate itself because Europe was filled with warmongering monarchies. In contrast, Paine presented republics as peaceful and argued that this was the form that America should adopt. He proposed that ‘the republics of Europe are all (and we may say always) in peace. Holland and Switzerland are without wars, foreign or domestic: Monarchical governments, it is true, are never long at rest’ (Paine 1988: 90). One way of shaping the meaning of a concept is by defining it in reference to a counter-concept, which is what Paine did in opposing Europe and America, monarchy and republic.

Paine fits closely with the figure of the innovating ideologist, and there are two dimensions of his influential polemics worth emphasising here. First, he comprehended and framed the conflict within a larger international context. America needed to become an independent member of international society, otherwise it would be condemned to the threat of war by virtue of its ties to Great Britain. For Paine, Great Britain was not a democracy cloaked in royal robes as Montesquieu had suggested, but an absolute monarchy masquerading as a republic. If America did not separate itself, it would be constantly caught up in British balance-of-power politics and the perpetual fighting that defined the European world of monarchies. Second, Paine insisted that independence must be followed by the foundation of republics. America needed to avoid the monarchical form that plagued Europe with continuous warfare and corruption. Only through republicanism could America be assured of peaceful relations and prosperity.

Moves towards independence unavoidably entailed a rejection of the British monarchy, as Paine made abundantly clear. This pushed the Americans towards defining themselves as republicans, almost by default: ‘once the decision for independence was made, there seems to have been no serious question that any other form of government was either possible or desirable’ (Kenyon 1962: 165). This stemmed from the widely understood notion that a republic was a polity that was not governed by a hereditary monarch. As Linda Kerber puts it, ‘usually republicanism was simply what monarchism was not’ (Kerber 1985: 475). This understanding strongly reflected the influence of Montesquieu, who had defined a republic simply as any regime where power was held by more than one individual. This conception was clearly reflected in John Adams’s definition of a republic as ‘a government whose sovereignty is vested in more than one man’ (quoted in Everdell 1983: 6). Montesquieu distinguished between two forms of republic: an aristocracy and a democracy. In this regard, ‘democracy’ had a reasonably fixed meaning – it was a direct form of rule found in the ancient polities of Greece – whereas ‘republic’ was a much broader and more contested term. ‘Republic’ signified a basic principle of sovereignty tied to the people, which remained compatible with a range of governmental forms, while ‘democracy’ entailed a direct form of government. This meant democracy was not of much interest to the Americans, but there was widespread consensus that sovereignty should be located with the people, which is what republicanism conveyed.

Despite the value placed in republicanism by the revolutionaries, monarchies – either mixed or absolute – undeniably remained the standard in international politics. The ancient republics had mostly fared poorly in historical judgement, while the more recent republics in the city-states of Italy, the cantons of Switzerland, the Dutch free states and Poland had done little to inspire confidence. The founders were very cognisant of these contemporary cases that provided ‘graphic examples of the disunity, absence of executive authority, and incapacity’ of republics (Ghelfi 1968: 163). Paine’s generous depiction was in stark contrast to the much more common perception of republics as sites of turmoil, instability and weakness. From the minor republics in Italy to their great forebear in Rome, all suffered similar fates: corruption and decline. This was not a particularly encouraging record for the Americans. As one anonymous author in 1776 concluded, ‘history ancient or modern will make few Republicans’ (W. P. Adams 1970: 414–15). Furthermore, the small community necessary to sustain the high levels of citizen participation and virtue required in republics was distinctly at odds with the trend towards larger states, and seemingly made republicanism a poor fit for the expansive territory of America. Simply put, republicanism did not appear a particularly wise or secure foundation on which to establish new states that would have to survive in a competitive international environment dominated by powerful monarchies (Bukovansky 2002: chs 3–4). These dangers of adopting republicanism were a recurrent theme in conservative writings up to 1776 (W. P. Adams 1970). It was only following Paine’s Common Sense that most Americans began to fully embrace republicanism, regardless of the warnings from history and Europe. Commenting on this shift, Thomas Jefferson observed in the summer of 1777 that Americans ‘seem to have deposited the monarchical and taken up the republican government with as much ease as would have attended their throwing off an old and putting on a new suit of clothes’ (quoted in Wood 1969: 92). These were clothes that remained most unfashionable in Europe, however.

The concept of republic further suggested a general ruling principle about the ends of government. Understood in this sense, the term was much closer to the Latin it was derived from, res publica. When taken as a principle of rule, it was possible for a republic to be compatible with any form of government, bar absolute monarchy. This served as the basis for its use in another sense, as representing a mixed constitution, in so far as it was still identified as being most able to provide the common or public good (res publica). The constitution could be functionally mixed – a separation of powers between the executive, legislative and judicial – or socially mixed – a balance of social orders between the one, the few and the many (Pocock 1975: 61–5). From this perspective, American independence did not have to mean an outright rejection of the British model. A system based on social orders was not possible, but a functional mix was. This is what would emerge later when a stronger union was forged in 1787.

Both democracy and republic rested on popular sovereignty, but the two entailed different governing forms: democracies were unmixed, while republics were associated with a mixed constitution. The former was framed by connotations of chaos, disorder and turbulence: the people as the mob. The latter became imbued with a sense of stability, strength and virtue: the people as citizens (Shoemaker 1966: 88). In this vision, the republican nature of America would separate the new states not only from the ancient democracies, but also from the corrupt monarchical regimes that dominated international affairs. In Europe the republican self-labelling of America was accepted, but the suggestion that they were especially different from previous republics was received with great scepticism.

Independence

In breaking free of British rule and declaring independence, the revolutionaries sought to establish a confederacy of republics. The relative tabula rasa on which the colonies had been built, combined with the disrepute monarchy had fallen into in America, meant that founding these new states on popular sovereignty was the most logical outcome. In this sense, even if democracy as forma regiminis (governmental form) was not central to the events taking place, clearly democracy as forma imperii (state form) was. The most important statement of the doctrine of popular sovereignty to emerge from revolutionary America was the Declaration of Independence. It announced in simple, assured language that governments derive their powers ‘from the Consent of the Governed’ (Continental Congress 2007: 165). In itself this proposition was not a new claim. Few rulers were bold enough to justify their power solely on rights of conquest, and most included some founding moment taken to embody the consent of the people. In the European context, consent was generally understood in a Hobbesian sense of the people contracting away their power. Once the people chose to invest the sovereign with power, they relinquished that power and were placed under the rule of the sovereign. This led to rule being legitimated in terms of historical right and custom, not in reference to (ongoing) consent. A British pamphleteer writing in 1776 summed up this conception of legitimacy: ‘Government is (certainly) an institution for the benefit of the people governed, that is for the whole people, but the whole of people have not a right to model Government as they please’ (quoted in Reid 1989: 21). In contrast, in America consent played a much more direct and active role. In a Lockean vein, the people construct a sovereign to rule over them, but they do not cede all their rights in the process. This was reflected in the declaration, which asserted that ‘whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these Ends [‘Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness’], it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government’ (Continental Congress 2007: 165). The people never fully relinquish their power, retaining a right to alter the government if those in power become corrupted. The artificiality, or perhaps more accurately, the ‘constructed- ness’ of government was emphasised, with the consent of the people playing a more active and immediate role.

Placing popular sovereignty at the heart of the Declaration of Independence may have made sense in the American context, but it was an awkward way of framing a document that was also meant for international consumption. In this regard, it is important to appreciate that its main purpose was asserting membership in international society. The declaration should in this sense be understood as ‘a document performed in the discourse of the jus gentium [the law of nations] rather than jus civile [the civil law]’ (Pocock 1995: 281). In the opening and closing paragraphs it is evident that this was an international dec-laration, in the same way as a state would declare war. It commences with the new United States seeking to ‘assume among the Powers of the Earth, the separate and equal Station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them’ (Continental Congress 2007: 165). What the revolutionaries took this to mean can be found in the document’s conclusion:

‘As FREE AND INDEPENDENT STATES, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which INDEPENDENT STATES may of right do’.

Continental Congress 2007: 170–1

This statement explicitly identifies the link between independence and external sovereignty, which, as David Armitage notes, ‘was quite novel at the moment Americans declared their independence’ (Armitage 2007: 137). What the document effectively represented was a claim to be considered as a member of the ‘club’ of sovereign states.

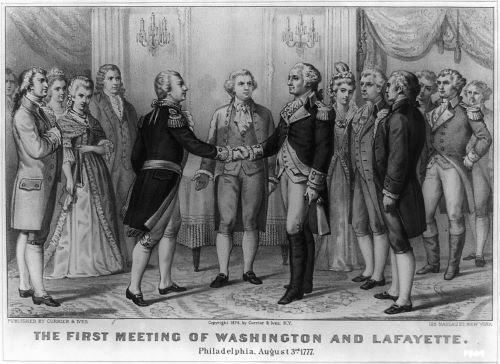

Unlike the French and Russian revolutionaries that would follow them, the Americans were not directly anti- systemic in intent: they were not trying to alter international society, but simply be accepted into it. Indeed, this could not have been otherwise: for America to be become fully independent and sovereign it needed to be recognised as such by other states. As David Armstrong explains, ‘their revolution was fought to win the right for their country to exist as a sovereign state. Such a status was inseparable from acceptance of the juridical structure that alone made sovereign statehood legitimate: the society of states’ (Armstrong 1993: 75). As such, the Americans largely sought to conform to what they understood as correct diplomatic behaviour. In January 1777, the American statesman James Wilson stressed that ‘in our Transactions with European states, it is certainly of Importance neither to transgress, nor to fall short of those Maxims, by which they regulate their Conduct towards one another’ (quoted in Armitage 2007: 65). Most Americans neither hoped nor expected that their revolution would spread to Europe and bring about the overthrow of monarchies (Rainbolt 1973). Schooled in traditional power politics, the revolution-aries were acutely aware that as a new, weak state on the periphery they would have to survive in a world dominated by powerful monarchies.

Considering this conservative desire to simply be accepted by other members of international society, the strong assertion that governments derive their powers ‘from the consent of the governed’ was an uncomfortable fit, as it directly challenged the prevailing standard of monarchical sovereignty. There was, however, a rather straightforward explanation: the document was also meant for domestic consumption. In claiming independence, America rejected the British monarchy and embraced republicanism, which necessarily entailed emphasising the constitutive role of the people. In this regard, the declaration is particularly significant because when the United States sought entry into the existing society of states, it did so while advancing an opposed conception of sovereignty, one that levelled an implicit challenge to the monarchical powers in Europe. As Peter Onuf notes, ‘the Revolution is as important for offering a new definition and model for the constituent part . . . as it is for promoting change in the international system’ (P. Onuf 1998: 73; original emphasis). The declaration effectively represented one of the first major breaches in the old dynastic international order. According to Martin Wight, with it ‘the floodgates were opened’ (Wight 1977: 160; see also Armitage 2007: 139–44).

The declaration was a powerful speech act in itself, but it could only have the desired effect if it was listened to and accepted by other states, and especially the great powers. And so the revolutionaries were rather alarmed when it was largely met by silence from Europe. Not long after the declaration the Continental Congress instructed its commissioners in Paris ‘to obtain as early as possible a publick acknowledgement of the Independancy of these States of the Crown and Parliament of Great Britain by the Court of France’ (quoted in Armitage 2007: 81). This would not happen until February 1778, at which time the French entered into an alliance with the United States, which was a significant step towards independence as it indicated great- power recognition. The treaty of alliance stated that one of its purposes was ‘to maintain the liberty, Sovereignty and independence absolute and unlimited of the said United States’ (quoted in Armitage 2007: 83). The international standing of the United States was not fully confirmed until the conclusion of the American Revolutionary War in 1783, when the Treaty of Paris explicitly included recognition by its former colonial master. The first article of the treaty announced that, ‘His Britannick Majesty acknowledges the said United States . . . to be Free, Sovereign, and Independent States’ (quoted in Armitage 2007: 87; original emphasis).

The United States secured its independence and membership of international society, but it also lost its one major bargaining chip in the European balance- of- power game. A confederacy of weak, fledgling republics on the periphery was of little interest, either as a threat or as a potential resource, to the dominant monarchical powers. The Marquis de Condorcet would observe in 1786 that American ‘independence is recognized and assured’, but the confederacy was also regarded ‘with indifference’ (quoted in Armitage 2007: 88). This lack of interest was reinforced by the republican character of the new confederacy. Absolute or mixed monarchies remained the standard, dictated both by custom and practice, and the great powers of Europe found little to worry about in the United States. Reflecting this opinion was John Andrews’s assessment in 1783: ‘A republican form of government is utterly inconsistent with the temper, disposition, and interest, of a great and powerful people’ (quoted in Ghelfi 1968: 62). The weakness of the Italian city-states, the tiny Swiss cantons, the Dutch free republics and Poland strongly suggested that these new republics on the other side of the Atlantic would not last long. The Prussian monarch presumed that the former colonies would soon ‘rejoin England and their former footing’. His Parisian ambassador concurred, describing the United States as, ‘a people poor, exhausted, and afflicted with the vices of corrupt nations’ (Morris 1965: 458–59). The early years of independence seemed to confirm the Prussians’ scepticism.

The Realities of Independence

By the middle of the 1780s it appeared that the American confederacy was not going to escape history. There was a growing belief that the republican experiment was in serious trouble. As Gerald Ghelfi observes, ‘throughout the literature of this decade Europeans constantly drew parallels between the causes which led ancient or modern republics to their ruin and the existence of similar “defects” in the Confederation’ (Ghelfi 1968: 102). Not long after the de jure sovereignty of the United States was recognised, its de facto sovereignty was increasingly called into question. In this regard, the reports written by the Marquis de Lafayette after his attempts to lobby on America’s behalf in the courts of Europe are particularly illustrative. He felt that perceptions of weakness were affecting the standing of the new confederacy, ‘which delights her enemies, harms her interests even with her friends, and provides the opponents of liberty with anti- republican arguments’ (quoted in Echeverria 1957: 127). Lafayette further noted that ‘it is foolishly thought by some that democratical constitutions, will not, cannot last; that the States will quarrel with each other; that a King, or at least a nobility, are indispensable for the prosperity of a nation’ (quoted in Ghelfi 1968: 126). Not only does this indicate that the United States was perceived as democratic, it illustrates the prevailing belief that popular states were not viable, with monarchies remain-ing the standard.

The low esteem the United States was held in stemmed not only from predominant opinions about republics, but also from the incapacity of the Continental Congress to act in a decisive fashion inter-nationally, which merely confirmed these prejudices. The American confederacy was increasingly incapacitated by individual states jealously guarding their sovereignty. As Peter Onuf notes, ‘the paradox of the Declaration [of Independence] is that the strong assertion of national identity should entail such a weakly articulated national government’ (P. Onuf 1998: 80; original emphasis). This contradiction was becoming untenable, at least in its existing guise. George Washington judged that if more powers were not granted to the Congress, the United States would ‘become contemptible in the Eyes of Europe if we are not made the sport of their Politicks’ (quoted in Ghelfi 1968: 133). The poor standing of the United States was illustrated in the difficulty it had securing loans and forging treaties (Ghelfi 1968: 130). Dutch bankers offered four financial lifelines to the United States during the 1780s, with progressively higher interest rates, reflecting a belief that the new republics were becoming an increasingly risky investment. In order to strengthen their international standing the Continental Congress appointed Adams, Franklin and Jefferson to seek out treaties with as many countries as possible, a task that proved near impossible due to perceptions of American incapacity. The Prussian king felt he had nothing to gain from a treaty, noting that ‘this so- called independence of the American colonies will not amount to much’. Britain was equally unconvinced, with the Earl of Sheffield concluding that ‘it will not be an easy matter to bring the American States to act as a nation; they are not to be feared as such by us’ (quoted in Ghelfi 1968: 136).

When considering the standing of the United States, French perceptions are especially instructive, as Paris was the source for most opinion on America in Europe, and it had also been the most sympathetic to the American cause (Venturi 1991: 4). The French position was very similar to that of Prussia and Britain. The minister to the United States, the Comte de Moustier, informed his king that the confederacy was hopelessly disorganised and suggested that this ‘phantom of democracy’ would inevitably degenerate into despotism (quoted in Echeverria 1957: 137). By 1787, the French government abandoned hope that the United States would hold together. The advice given by de Moustier is revealing:

It appears, sir, that in all the American provinces there is more or less tendency toward democracy that in many this extreme form of government will finally prevail. The result will be that the confederation will have little stability, and that by degrees the different states will subsist in perfect independence of each other. This revolution will not be regretted by us. We have never pretended to make of America a useful ally; we have had no other object than to deprive Great Britain of that vast continent. Therefore we can regard with indifference both the movements which agitate certain provinces and the fermentation which prevails in Congress. (Quoted in Echeverria 1957: 138)

There was clearly no concern here about popular doctrines in America setting a dangerous example. Rather, the confederacy was deemed unthreatening, if not irrelevant, for France and Europe.

Talk of chaos, anarchy and decline in the United States was not limited to diplomatic opinion. It was also common throughout the European press, which made frequent comparisons with the unfavourable example of the tumultuous Dutch free republics (Venturi 1991: 59, 97, 126). After Thomas Jefferson was appointed as the American plenipotentiary minister in France in autumn of 1784, his job was one of public relations as much as diplomacy. As Franco Venturi notes, ‘Jefferson’s effort was directed toward international opinion . . . to persuade the world that the political creature born beyond the ocean was alive and well’ (Venturi 1991: 110). This was a difficult task, especially as many Americans themselves were becoming more uncertain. In this regard, the Shays’ Rebellion in 1786 was a catalyst in strengthening perceptions that the confederacy was in a state of crisis. Shortly after the rebellion, John Jay, the American secretary for foreign affairs, summed up the problem:

‘To be respectable abroad it is necessary to be so at Home, and that will not be the Case until our public Faith acquires more Confidence, and our Government more Strength’ (Ghelfi 1968: 134). Lafayette, America’s greatest supporter in Europe, conceded that perceptions of weakness and incapacity ‘did not seem to me quite destitute of a foundation’.

Ghelfi 1968: 126

Later, in the fifteenth Federalist, Alexander Hamilton bluntly described the situation:

We may indeed, with propriety, be said to have reached almost the last stage of national humiliation. . . . The imbecility of our government even forbids them [‘foreign powers’] to treat with us: our ambassadors abroad are the mere pageants of mimic sovereignty.

Carey and McClellan 2001: 69

Within the confederacy there was also a growing concern that its people were perhaps not so special as to possess the high level of virtue presumed necessary to sustain republics. Those agitating for a solution feared that all the vices that republics must avoid to survive – faction, corruption, self- interest – were far too prevalent. The source of these problems was regularly located in the overly democratic nature of state constitutions. In trying to guard against the dangers of executive tyranny, too much power had been handed to the people, who were subsequently failing the vital test of virtue. That a natural aristocracy did not appear meant that the concentration of power in the legislative branch was most troublesome (Pocock 1975: 516–17). The perceived results of the legislatures were not anarchy or licentiousness – the acknowledged and expected vices of a democratic system – but unexpectedly a kind of tyranny. Historical wisdom suggested that this was supposed to be found in the excesses of monarchies, not democracies. The classically minded John Adams complained that ‘a democratic despotism is a contradiction in terms’ (quoted in Wood 1969: 62–3). By contrast, Jefferson argued that a concentration of power was ‘precisely the definition of despotic government’, even if that concentration was found in the legislative branch chosen by the people. This was because the end results were the same: ‘one hundred and seventy-three despots’ were just ‘as oppressive as one’. Despotism, long regarded as the vice of monarchy, now seemed to afflict the United States, which had purposely been founded on the principle of popular sovereignty partly to avoid such a danger. This growing dissatisfaction was summed up in Jefferson’s lament that ‘an elective despotism was not the government we fought for’ (quoted in Corwin 1925: 519).

Failings at home and weakness abroad combined to create a palpable sense of crisis in the ‘United’ States. Independence was not supposed to result in ‘mimic sovereignty’ and ‘democratic despotism’. These failings raised fears that Europe would soon try to carve up the United States as it had Poland. Disunion and weakness left it open to the designs of the great powers, whose appetite for conquest never appeared to be sated. Another possible scenario was that America would, in the words of Hamilton,

be gradually entangled in all the pernicious labyrinths of European politics and wars; and by the destructive contentions of the parts, into which she was divided, would be likely to become a prey to the artifices and machinations of powers equally the enemies of them all.

Carey and McClellan 2001: 31

Beyond the dangers of being dragged into the European system, there was the related threat of America becoming Europe. The fear was that without a strong national government, the confederacy would break down into a regional international society. Individual states closely guarding their freedom created the risk that the United States might descend into a Hobbesian state of nature composed of ‘a number of unsocial, jealous and alien sovereignties’, in Jay’s words (Carey and McClellan 2001: 6).

Those that agitated for a stronger union worried that without one the United States was destined to suffer from the same systemic forces that brought constant conflict in Europe and the diminution of liberties within those states (Hendrickson 2003: 13). Hamilton was particularly sceptical about the possibility of sovereign states within America remaining at peace in an anarchical environment:

‘To look for a continuation of harmony between a number of independent unconnected sovereignties, situated in the same neighbourhood, would be to disregard the uniform course of human events’.

Carey and McClellan 2001: 21

In stark contrast to Thomas Paine’s optimism that republics would enable more peaceful international relations, Hamilton denied any difference: ‘Have republics in practice been less addicted to war than monarchies? Are not the former administered by men as well as the latter? Are there not aversions, predilections, rivalships, and desires of unjust acquisition, that affect nations, as well as kings?’ (Carey and McClellan 2001: 23–4). If a stronger union was not forged, and instead a regional international society emerged as the confederacy fell apart, the great fear was that the American republics would follow Europe into despotism. The constant demands of war would likely cause an increase in executive powers at the expensive of liberties and the legislature (Carey and McClellan 2001: 26–31).

A fear of being attacked or becoming Europe combined with a sense of crisis emerging from the overly democratic state constitutions and the inability of the weak Congress brought matters to a head, leading to the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Observing this state of affairs, Jay wrote that ‘experience has pointed out errors in our national government which call for correction, and which threaten to blast the fruit we expected from the tree of liberty’ (quoted in Ghelfi 1968: 162). The United States faced the prospect of strengthening the union or risking its dissolution. The basic problem stemmed from the location of sovereignty within the existing confederacy. The belief that sovereignty was indivisible meant that it could not be shared between the states and the union. Ultimately sovereignty had to reside with one or the other. During the discussions at Philadelphia and subsequent debates over ratification, significant reflection took place on forms of state and methods of rule, resulting in plans for the forging of a stronger union. The ultimate solution was one that drew on the European model of statehood without abandoning America’s experiment with popular sovereignty. It would truly be a ‘republican remedy’ to the diseases that beset the United States (Carey and McClellan 2001: 49).

Republican Remedies

Overview

In forging a stronger United States the founding fathers were faced with a host of difficult issues. The most challenging revolved around sovereignty and the nature of the union. If the American confederacy was to hold, sovereignty could not ultimately lie with the individual states. Should it then be located at the national level? But surely such a concentration of power would lead to despotism and the abandonment of republicanism? There also remained considerable doubts about the viability of a republic existing across such a great territory. As Adam Ferguson explained, ‘monarchies are generally found, where the state is enlarged in population and in territory, beyond the numbers and dimensions that are consistent with republic government’ (quoted in Ghelfi 1968: 35). This opinion was reflected in diplomatic correspondence. One British agent in New York wrote that ‘a Republican system, however beautiful in theory, is not calculated for an extensive country’ (quoted in Ghelfi 1968: 35). The Prussian monarch offered a similar assessment: ‘The extent of the country would alone be a sufficient obstacle to America’s political success, since a republican government had never been known to exist for any length of time where the territory was not limited and concentered’ (quoted in Ghelfi 1968: 36). Could the Americans prove these sceptics wrong? How could popular rule operate in such a large territory, while guarding against republican vices and democratic dangers?

The proposed constitution that emerged from Philadelphia in 1787 was a remarkable document, which managed to arrive at a viable solution to these challenges the United States then faced. The constitution re-envisaged the popular base of the United States. In it, the people were introduced as the source of sovereignty, while at the same time, they were removed by having their role limited and restrained in the exercising of this sovereignty.

Popular Sovereignty

The sense of impotency abroad and discord at home was understood as a failure of the existing constitutional structure. A federal government stronger than the ineffectual Continental Congress was regarded as necessary to fend off the dangers posed by Europe. Admitting this, the socio- political realities of America dictated against the straight transferral of sovereignty upwards to a new national government. The individual states were jealous of their independence, and many were highly sceptical about the wisdom of ceding their freedoms. Indeed, it would ultimately take a civil war half a century later to fully solidify the union. Along with more parochial concerns, there was a greater issue about whether a federal government was compatible with republicanism. As noted, history and theory dictated that republics could only exist in small polities, which suggested that the separate states needed to maintain their independence. Anti-federalists used Montesquieu to remind Americans of the impossibility of large republics, a historical lesson most famously demonstrated by Rome, which had lost its republican character with its expansion. They warned that a federal government would be too big to be republican. Federalists countered by emphasising that an anarchical system of ‘jealous sovereignties’ transplanted to America would soon bring with it the corruption and despotism that afflicted European states. For republicanism to work in America, the founders had to reconcile the need for a stronger union with the realities of states protective of their freedom as well as wide-spread scepticism about the viability of a great republic. Sovereignty had to be moved upward, but not completely, as it had to be shared between the state and federal level. This was achieved through an innovative revision of the doctrine of popular sovereignty.

Simply appealing to popular sovereignty was not enough to resolve the issue of sharing sovereignty between state and national levels, but it did offer a way of reconceptualising the problem. Peter and Nicholas Onuf explain that ‘by invoking and implementing, “popular sovereignty,” Federalists could challenge this monopoly [of political power by the states] and provide a theoretical rationale for a powerful yet limited government for the federal republic’ (P. Onuf and N. Onuf 1993: 131). The crucial move in the constitution was replacing the phrase ‘we the states’ with ‘we the people’. The federalists persuasively argued that the separate states did not represent separate peoples. This enabled them to suggest that those who were against the federal system on the grounds that sovereignty was indivisible fundamentally misunderstood where this power ultimately lay. Both federal and state levels were equally representative of one American people, which remained the constitutive power. As sovereignty resided with the people, and not the states, it was theirs to distribute as they saw fit. The American people retained sovereignty by being its constitutive basis. They did so in a more immediate manner than in Europe through constitutional conventions, which operated as the ‘founding moment’ where the people constituted and delegated sovereignty (Palmer 1959: 214). Securing ratification of the constitution allowed for the creation of a stronger federal government, able to go beyond ‘mimic sovereignty’ and operate effectively internationally.

The founders had to be careful that in identifying sovereignty as residing in the American people they did not actually cede too much power to them. As Daniel Deudney observes, the founders ‘were committed to popular sovereignty, but saw democracy as a source of instability and insecurity’ (Deudney 2007: 165). Reflecting this, they sought to distinguish between the centrality of the people in legitimating rule and the more limited role they should play in actually governing. They did this through emphasising the distinction between the people as the constitutive power and the people as the constituted power (Pocock 1975: 517–18). The people were sovereign, they remained the constitutive power, and in turn, they delegated the constituted (legislative and executive) power to their representatives, who were of the people but separate from them. Sovereignty remained absolute, as the people were the constitutive basis of the United States and they retained this power in a more active and vigilant sense than in Europe, while legislative and executive powers were redistributed between state and federal levels. Sovereignty did not rest on a pact between ruler and ruled, as the people performed both of these functions. Without further revisions this suggested, in the words of James Otis, ‘a government of all over all’ (quoted in Wood 1969: 223), which is certainly not what the founders wanted. To avoid this scenario it was necessary to rethink another crucial concept – representation – which would reconcile these two roles played by the people.

Representation

While a long tradition of political thought warned against the extensive exercise of power by the people, the immediate experience of the colonial period had left the framers of new state constitutions more wary of the one than the many. Not long after independence, as noted, fears instead appeared about the despotism of the many, with a belief that state constitutions were overly democratic. Drawing on contemporary sources, Gordon Wood highlights the shift in the discourse:

‘It is a favourite maxim of despotick power, that mankind are not made to govern themselves’ – a maxim which the Americans had spurned in 1776. ‘But alas!’ many were now saying, ‘the experience of ages too highly favours the truth of the maxim; and what renders the reflection still more melancholy is, that the people themselves have, in almost every instance, been the ready instruments of their own ruin.’

Wood 1969: 397

This is the context within which a system of representation was further developed during the Constitutional Convention and subsequent ratification debates. In the formulation successfully propagated by the Federalists, representation would ensure that popular sovereignty did not entail popular rule in the form of democracy. In this regard, Wood is not exaggerating when he states that ‘no political conception was more important to Americans in the entire Revolutionary era than representation’ (Wood 1969: 164).

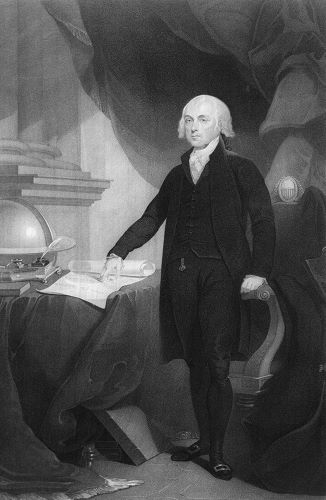

Representation, as James Madison so aptly put it, would be the ‘pivot’ on which the American republic would turn (Carey and McClellan 2001: 328–9). It was hardly a new theory when it was afforded such a central role in the constitution of the United States. Earlier versions could be found in medieval times and it was notably present in the British mixed constitution. Yet a mixed constitution based on social orders could not exist in America as there was nothing to mix. Instead, the branches of government that represented the one, the few and the many in Britain came in the United States to be different representations of the same collective people. Bicameral parliaments did not have two houses representing different social classes, but were a double representation of the same people (Wood 1969: 248–50). The result was, as Wood notes, that ‘the American states were neither simple democracies nor traditional mixed governments. They had become in all branches governments by representation’ (Wood 1969: 387). Power was not exercised directly. There was a distinction between ruler and ruled that did not traditionally exist in democracies, where the same collective people had held power and exercised it. In the United States, the people remained the locus of sovereignty, as in a democracy, but subsequently alienated their powers to elected representatives. Representation thereby allowed for the creation and maintenance of a ruling elite that would govern, one selected by merit and regularly answerable to the people. In this regard, Manin notes, ‘representative government was instituted in full awareness that elected representatives would and should be distinguished citizens, socially different from those who elected them’ (Manin 1996: 94). And in a large republic there was a bigger talent pool to draw leaders from. In this system of representative government the tensions between the necessities of popular consent and the dangers of popular rule were, to some degree, reconciled. Representation enabled the former, while limiting the latter.

The centrality of representation in defining the strengthened United States was definitively outlined in Madison’s tenth Federalist paper, a work that marks a peak in both political theorising and rhetoric during the founding period. This was a particularly clear and successful case of ideological innovation in which Madison renovated the concept of republic in such a way that representation became central and a virtuous citizenry was no longer necessary, something that previously would have been a contradiction in terms. Representation became the defining feature of a republic, separating the American state from both the monarchies of Europe and the democracies of ancient Greece. The definition of democracy Madison provided was the standard one identified earlier: ‘a society consisting of a small number of citizens, who assemble and administer the government in person’ (Carey and McClellan 2001: 46). Reflecting commonplace interpretations, he found the historical record particularly troubling: ‘Such democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security, or the rights of property; and have, in general, been as short in their lives, as they have been violent in their deaths’ (Carey and McClellan 2001: 46). While Madison was working well within dominant understandings of democracy, he departed from established thought in offering a drastic reformulation of republic. As noted earlier, republics and democracies were often seen as similar, if not as synonymous, because of a shared popular base. Madison, however, drew a sharp distinction between the two. The difference was that a republic is ‘a government in which the scheme of representation takes place’ (Carey and McClellan 2001: 46). In the fourteenth Federalist he repeated this claim in an even more explicit fashion: ‘In a democracy, the people meet and exercise the government in person: in a republic, they assemble and administer it by their representatives and agents’ (Carey and McClellan 2001: 63).

Identifying representation as the characteristic that separated a republic from a democracy contrasted drastically with common usage in both America and Europe. Following this definition there were no republics in ancient times, a most untenable position. Reflecting on this, the Onufs ask, ‘Why would Madison have taken a position as artificial, even silly, as this?’ (P. Onuf and N. Onuf 1993: 79). The likely answer is the rhetorical capital gained from implying that Madison’s opponents were democrats (P. Onuf and N. Onuf 1993: 79). Madison’s distinction stemmed more from political exigencies than theoretical insights, as he was trying to strengthen the Federalist position against those sceptical of the new constitution. Indeed, John Adams later reprimanded Madison for his rhetorical manoeuvring:

‘His distinction between a republic and a democracy . . . cannot be justified. A democracy is really a republic as an oak is a tree, or a temple a building’.

quoted in Stourzh 1970: 55

In following the distinctions outlined by Montesquieu, Adams saw the two concepts as related because both were based on popular sovereignty. Madison viewed matters differently, complaining of ‘the confounding of a republic with a democracy; and applying to the former, reasonings drawn from the nature of the latter’ (Carey and McClellan 2001: 63). For Madison, the crucial difference was in how popular rule was exercised. In one, popular power operated but it was controlled and channelled through representation, which created a virtuous balance of liberty and stability. In the other, the unrestrained will of the demos meant a constant ‘turbulent existence’, where the people suffered from the ‘tyranny of their own passions’ (Carey and McClellan 2001: 327–8). Simply put, in Madison’s formulation what separated republic and democracy was the nature and consequences of popular rule. Representation offered the possibility for a state to be founded on popular sovereignty and ruled by the people, but not in the direct and dangerous manner found in democracies.

For supporters of the new constitution, it was the system of representation that would distinguish the American republic from the historical record. In providing the theoretical foundations for the new federation, Madison was most explicit in identifying representation as the ‘pivot’ separating popular sovereignty from democratic rule, and America from Athens. This was a position Paine would later adopt even more forcefully in Rights of Man.The centrality of representation identified the American experiment as unique, and the historical record as largely irrelevant,

as most of the popular governments of antiquity were of the democratic species; and even in modern Europe, to which we owe the great principle of representation, no example is seen of a government wholly popular, and founded, at the same time, wholly on that principle.

Carey and McClellan 2001: 63–4

Madison argued that what made the United States different, and likely to escape the historical tendency of republican failure, was that through representation it was possible to have both popular sovereignty and a form of popular rule, without suffering from the dangers that come from the directness of democracy. In the thirty-ninth Federalist he clearly distinguished between the two:

‘It is essential to such a government, that it be derived from the great body of the society . . . It is sufficient for such a government, that the persons administering it be appointed, either directly or indirectly, by the people’.

Carey and McClellan 2001: 194–5; original emphasis

The people played a much more active part in governing compared with the Hobbesian model of sovereignty found in Europe, but representation still served to restrict the role they would play.

Representation offered a way for the United States to enjoy the advantages of popular rule, free from the wars and corruption that marked monarchical regimes, without succumbing to the failings that defined democracy in ancient Greece. From a more distant historical vantage point, it is valuable to note that at this time representative government was largely defined against democracy, which was still seen as a direct form of rule. The former was praised and lauded, the latter remained in disrepute. Prevailing opinion at the Convention still largely rejected the idea of democracy.3 John Adams was most explicit in his judgement: ‘Remember, democracy never lasts long. It soon wastes, exhausts, and murders itself. There never was a democracy yet that did not commit suicide.’ Benjamin Rush echoed this viewpoint:

‘A simple democracy has been aptly compared . . . to a volcano that contained within its bowels the fiery materials of its own destruction’.

quoted in Lipson 1964: 45

Democracy was widely seen as inappropriate for the new republic. Indeed for many, democracy was not only ill suited to modern eighteenth-century states, it had not even been appropriate for the ancient Greeks (J. Roberts 1994). Through the principle of representation the United States could be based on popular sovereignty, while distancing itself temporally and theoretically from democracy. Representation divided the people’s two bodies: the constitutive power – the people as sovereign – was separated from the constituted power – the representatives of the people exercising power in the executive, legislative and judicial branches. This system was a clear improvement on ancient democracy: ‘The public voice, pronounced by the representatives of the people, will be more consonant to the public good than if pronounced by the people themselves, convened for the purpose’ (Carey and McClellan 2001: 46).

Fear and Faith

During the Constitutional Convention and the debates that followed the people were simultaneously regarded as both a source of strength and a threat to the viability of the United States. On the one hand, the people were identified as the constitutive base of the new republic. The United States separated itself from the absolute monarchies of Europe and the corrupted British mixed regime by constructing itself on the active and ongoing consent of the people. Alexander Hamilton put it in these terms:

‘The fabric of American empire ought to rest on the solid basis of the consent of the people. The streams of national power ought to flow immediately from that pure original fountain of all legitimate authority’.

Carey and McClellan 2001: 112

This was a fundamentally different conception of sovereignty to that which prevailed elsewhere in international society at the time. On the other hand, the correct mixture of liberty, stability and strong government that the Americans sought could not be secured through the people ruling directly, as in a democracy. Through the essentially aristocratic principle of representation, the role of the people would be limited and controlled, preventing popular sovereignty spilling over into direct rule. James Madison was clear on this point:

The principle of representation was neither unknown to the ancients, nor wholly overlooked in their political constitutions. The true distinction between these and the American governments, lies in the total exclusion of the people, in their collective capacity, from any share in the latter, and not in the total exclusion of the representatives of the people from the administration of the former. The distinction, however, thus qualified, must be admitted to leave a most advantageous superiority in favour of the United States.

Carey and McClellan 2001: 329; original emphasis

The prudential reasons that warned against democracy, combined with the practical necessities of enacting a popular form of rule in a great territory, made representation fundamental to the new constitution of the United States.

The beauty of representation was that it effectively allowed for rule of the people without rule by the mob. This point was expressed with great clarity at the time by Jean Louis Delolme:

‘A representative Constitution places the remedy in the hands of those who feel the disorder, but a popular Constitution places the remedy in the hands of those who cause it’.

quoted in Ghelfi 1968: 191; original emphasis

In activating popular consent while carefully limiting the actual input of the people in governing, representation truly acted as the ‘pivot’ of the new constitution. The principle that was supposed to enable popular sovereignty through overcoming the practical difficulties of extensive republics also dealt with the qualitative shortcomings of democracies. The resolution to the problems of the failing confederacy was thus a distinctly dialectical one, combining a unique mix of faith and fear in the people.

Conclusion

The founding of the United States did not, at first, significantly alter conceptions of democracy as a governmental form, but as a form of state – namely popular sovereignty – it was asserted in a very powerful manner. As Alexis de Tocqueville would soon observe,

‘if there is a single country in the world where the doctrine of the sovereignty of the people can be properly appreciated . . . that country is undoubtedly America’.

Tocqueville 2003: 68

Despite being founded on a conception of sovereignty that differed from the great powers of Europe, the United States was not perceived as a challenge to their legitimacy or standing. European monarchs, confident in their claims to rule, were not threatened by a weak, peripheral state that had yet to prove that its republican experiment would not end in failure. Furthermore, the Americans were not anti- systemic in intent, as later revolutionary actors in France and Russia would be. They were not trying to over-turn international society; quite the opposite: they sought membership and acceptance. At the same stage, as was most clearly seen in the Declaration of Independence, the Americans were not simply conforming to existing understandings of statehood. This was further evidenced in the adoption of a republican constitution founded on popular sovereignty, and in instituting a form of government where the people played a much greater role than in Europe. In so doing, the Americans were – rather inadvertently – introducing a new, and revolutionary, conception of sovereignty into international society. In this regard, David Armstrong describes America’s role well, noting how its emergence contributed to ‘the dilution of the specific principle of international legitimacy of the eighteenth century’ (Armstrong 1993: 76). Such an example had potential to become more challenging as revolutionary sentiment swelled on the other side of the Atlantic (Venturi 1991: 137).

In considering the role played by the founding of the United States in the emergence of democracy in international politics, it is also necessary to take a longer view. On the fiftieth anniversary of American independence, Thomas Jefferson wrote that the Declaration of Independence was ‘an instrument, pregnant with our own and the fate of the world’ (quoted in Armitage 2007: 1). This was an accurate assessment by the man who drafted the document. The revolution was a determinative step in the transition towards a society of sovereign states spanning the globe (Armitage 2007: 103). The success of the United States in its attempts to found and maintain a state based on, and animated by, the consent of the people was most consequential in the rise of popular sovereignty in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Furthermore, even if the concept of democracy was generally denounced, ignored or repudiated, many key dimensions of the modern representative form of democracy that would later emerge were initially explored in powerful ways in the United States. In this regard, Bernard Manin notes the remarkable situation that ‘what today we call representative democracy has its origins in a system of institutions . . . that was in no way initially perceived as a form of democracy’ (Manin 1996: 1). James Madison announced the representative system as being a republic, not a democracy, but in time this difference would fade, as representation became identified as a fundamental component of modern democracy. This is one example of the revisions that took place in the United States, helping to lay the foundations for later conceptual shifts in democracy. And if it would take longer for the full impact of America’s founding to become apparent, this was, in part, due to the outbreak of a great revolution on the other side of the Atlantic.

Endnotes

- The founders were schooled in the classics, and these texts were widely read, cited and used during the founding period (Ghelfi 1968: ch. 3; Wolverton 2005).

- Rule by one could be either monarchy or tyranny, rule by the few either aristocracy or oligarchy, rule by the many either politeia or democracy.

- Hamilton was perhaps alone in coining the phrase ‘representative democracy’, but did so in private correspondence and did not use the term repeatedly.

See source for bibliography

Chapter 3 (45-73) from The Rise of Democracy: Revolution, War and Transformations in International Politics since 1776, by Christopher Hobson (Edinburgh University Press, 10.07.2015), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.