The idea of Europe took on various forms over the century.

By Dr. Justine Faure

IRHiS Institut de Recherches Historiques du Septentrion

Université de Lille

By Dr. Heike Wieters

Simone Veil Fellow

Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich

By Dr. Tonio Schwertner

Professor of History

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

By Dr. Károly Halmos

Professor of History

Eötvös Loránd University

Introduction

At the beginning of the twentieth century, European civilisation extended far beyond the geographical borders of the continent. Colonies and dominions throughout the world belonged to this cultural Europe. This reach of what was considered European culture provided a feeling of exceptionality to many inhabitants of European metropoles. At the same time, the power and reach of European culture had begun to be challenged. Nation-building at home, along with the increasing participation of people in politics on the national level, had also become important issues.

One of the pillars of this culture-based European identity was Western Christianity (WC). At the beginning of the First World War there were two empires on the territory of geographical Europe with predominantly Orthodox or Muslim populations: the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire, respectively. The Habsburg Empire was also home to a substantial minority of non-WC subjects. By the end of the war, all of these empires were gone and were replaced by newly established states. However, in this Europe of nations, the idea of supra-national organisation still thrived, and the twentieth century remains a crucial period for the idea of Europe. During that period, various structures were created which, over the years, have made it possible to transcend national sovereignty in many areas through the institutionalisation of the European idea. This progressive but incomplete integration during the twentieth century is characterised by three major features.

First of all, it took place within specific time frames, marked by periods of acceleration and stagnation. Secondly, integration has been driven by a wide variety of actors, from political, economic, and intellectual elites, to the crucial influence of public opinion, emerging from the 1990s onwards. Finally, the idea of Europe has taken on various forms over the century and has represented issues that sometimes differ greatly from one country to another or from one stakeholder to another.

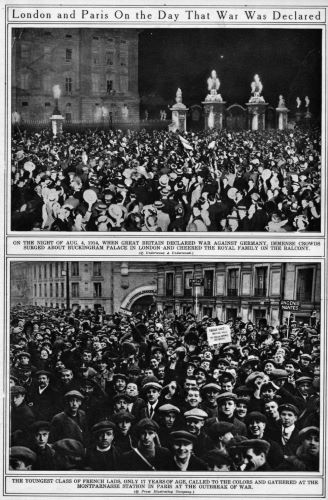

The First World War and the 1920s

The First World War was a seminal event for the development of the European idea in the twentieth century. After a fratricidal and deadly war between the European countries, hopes of overcoming nationalism and building a common identity grew amongst many Europeans. The post-war period was also marked by the international affirmation of the United States. On 8 January 1918, the president of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, made a speech before Congress. In his famous fourteen points, Wilson stated his vision for a stable, international post-war system. The speech, which functioned as the American basis for the negotiation of the peace treaty in Versailles, proposed the principles of international cooperation, free trade, national self-determination, and collective security—i.e. an international order designed according to American interests.

Wilson’s ideas were partly influenced by European scholars and politicians, such as the Czechoslovak statesman Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (1850–1937). Masaryk was one of the intellectuals associated with the British weekly magazine New Europe, which promoted the transformation of the continent into a federation of nations. Masaryk had close contacts in academic and political circles in the US, had met Wilson during the war and, according to the historian Larry Wolff, “shaped Wilson’s mental map” of the post-war reorganisation of Europe.

However, the 1920s quickly revealed the problems of internationalism and of certain states’ unwillingness to participate in such a system: first of all on the American side, when the Senate refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, but also in Europe. This prompted a discussion on new approaches for easing territorial tensions among European states, commitment to collective security, and—significantly—Germany’s unwillingness to make vaguely defined reparation payments. The consolidation of the United States as a great economic and military power and the emergence of the Soviet Union also seemed to indicate a relative weakening of European powers.

In this context, the Austrian-Japanese activist Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi (1894–1972) developed his proposal for the Pan-European Union, an idea of Europe also encouraged by the activities of the International Commission on Intellectual Cooperation of the League of Nations. Coudenhove-Kalergi argued for a united Europe, underpinned by ‘European patriotism’, calling for the unification of continental Europe against Britain and Soviet Russia. According to him, only a Pan-European Union could guarantee freedom, prosperity and—above all—independence from American and Soviet influence. Coudenhove-Kalergi not only disseminated his ideas widely through his newspaper Paneuropa, but also managed to secure the support of prominent figures of the political sphere in Europe—most notably Aristide Briand (1862–1932), the contemporary foreign minister of France.

Briand also played a major role in Franco-German reconciliation, which was often seen as an essential precondition for the construction of a peaceful Europe. He and his German counterpart Gustav Stresemann were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1926 for their efforts. In a resounding speech before the League of Nations on 5 September 1929, Briand imagined a “federal link” and a “link of solidarity” between European countries, a vision which took concrete form in September 1930, in a memorandum outlining the contours of a peaceful and united Europe.

The First World War also triggered awareness of the continent’s waning diplomatic and economic force, especially in relation to the rising power of the United States. In this context, the industrial and business community endeavoured to bring the European economies closer together, guided by French writer Gaston Riou’s (1883–1958) injunction to “Unite or die.” For example, the International Steel Agreement and the Potash Cartel were created in 1926, under the leadership of the Luxembourg industrialist Emile Mayrisch.

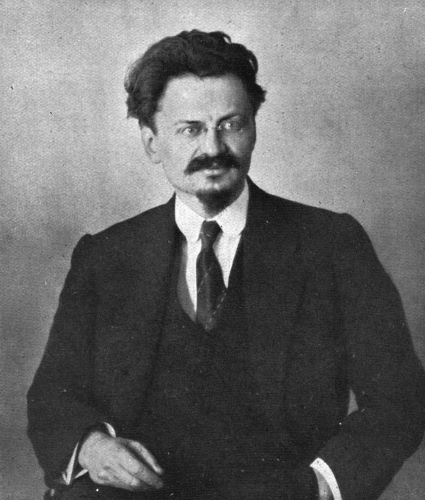

Leaders of socialist movements also proposed a united Europe, but their designs differed in terms of the degree of political integration envisioned. The Russian revolutionary leader Leon Trotsky (1879–1940)—disagreeing with Lenin (1870–1924)—published a socialist vision of the United States of Europe against the backdrop of a strengthened United States. In an article published in the newspaper Pravda on 30 June 1923, Trotsky argued for a proletarian European Union. In his view, capitalism had proven unable to solve the economic problems that had plagued the European continent since the end of the war. He stressed that, given the differing pace of proletarian revolutions in each country, “tight economic cooperation of the European people” in a united and socialist European federation was a necessary intermediate stage towards world revolution. Trotsky argued that a united Europe of workers and peasants would resolve the tensions between European states over natural resources and reparations. He proposed property and wealth taxes to refinance reparations that would be distributed from a common European reparations-budget. Customs barriers would be unnecessary in this centrally planned and unified European economy. According to Trotsky, only a socialist European Union could prevent the United States from eventually taking control of Europe.

The International Federation of Trade Unions (IFTU), founded in 1919, proposed a less wide-reaching concept of a united Europe. They advocated a European customs union merely as an intermediate step towards a fundamental global economic policy. In 1925, the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) adopted a new programme, the so-called ‘Heidelberg Programme’, in which the SPD underscored its commitment to strive for a European economic entity by democratic means and emphasised that the abolition of trade barriers would be the first step towards the creation of the United States of Europe.

Many of the newly formed states in East and South-East Europe, such as Czechoslovakia and Romania, were composed of heterogeneous parts, and had to—quite literally—put themselves on the map. They engaged in nation-building activities and had to fight for their own survival in the new post-war order, seeking their own geopolitical patrons. While Coudenhove-Kalergi’s Pan-European proposals had some resonance with Eastern European states, there was a more pressing issue for these nations, namely that of Central Europe. The question of how to manage the legacy of the Austro-Hungarian empire after its collapse engendered many plans, proposals, and visions for a new order in the region. For example, Masaryk’s book The New Europe: The Slav Standpoint (Nová Evropa: Stanovisko slovanské, 1918) proposed an anti-German Central Europe based on Slavic nations: a united Poland, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. The German ideas of a Mitteleuropa (Middle Europe) or a Zwischeneuropa (In-between Europe) were also influential in this debate. The latter concept had a geopolitical connotation, since it envisaged a political conglomerate separating the West from Hintereuropa (End Europe, a term denoting Russia).

The concept of a Mitteleuropa had been articulated in 1915 by the German liberal politician Friedrich Naumann (1860–1919). His plan proposed voluntary economic cooperation and integration, as well as the substitution of sovereign nation states for national autonomies. Naumann’s ideas caused intense debates in Hungary and other countries included in the plan. The central question was whether economic integration meant economic and political subordination to Germany. The economic background to Naumann’s plan was the fact that Germany had overtaken the hereditary provinces of the Habsburg Monarchy as dominant investors in the region. As the states of the East and South-East of Europe were mostly agrarian, they had to decide if they could accept these very German proposals. There was a cleavage between agrarian and mercantile (viz. industrial) interests. Those representing the interests of large-scale farming were in favour of the Middle Europe Plan, while those representing the country’s large-scale industry were against it.

The 1930s and the Second World War

The fragile blossoming of the European idea during the 1920s—founded on the pillars of a common culture, pacifism, and economic unification—was crushed first by the onset of the Great Depression in 1929 and the exacerbation of protectionism that had already been present in the previous decade, and then by the rise of nationalism and the strengthening of authoritarian, fascist, and Nazi regimes—a process that had begun in East-Central Europe as early as the 1920s.

Conservative designs of Europe in the 1920s and ‘30s often combined anti-American and anti-Bolshevik sentiments with an elitist and hierarchical social model. For example, the Abendland (Occident) movement, most influential in Germany but with ties to France, envisioned Europe as a Christian (Catholic) unity dominated by the German and French nations and with a social structure inspired by the Middle Ages. Such plans were revealing, in that they reflected primarily on the question of which role Germany might play in a unified Europe. The most violent of these designs was undoubtedly the Nazis’ concept of Lebensraum (living space).

Drawing on racist, anti-Semitic, and social-Darwinist ‘theories’, Hitler outlined his concept of a Germanised Central Europe in his book Mein Kampf (My Struggle, 1925). The National Socialist focus on reconstructing the agriculturally rich parts of Central and Eastern Europe stemmed from their plans and fantasies of creating an autarkic European entity. The Nazis wanted to expel and exterminate the people they considered ‘racially worthless’ and to recolonise the areas they inhabited with Germans who would cultivate the territory.

With the exception of the Lebensraum concept, which the Nazi authorities began to enforce during the Second World War, National Socialist ideals of post-war Europe remained very vague. Senior officials merely stressed the necessity of the Third Reich’s dominance in Europe, and of the reconstruction of the occupied European states according to the German model. Thus—with Hitler’s attempt to reclaim the European idea by linking it to an anti-Semitic and anti-Bolshevik Neuordnung (Rearrangement, usually referred to as New Order)—the period after the 1920s was a very dark one for supporters of a united Europe.

While there were attempts by Britain and France to develop trade and to establish closer contact with the nations ‘beyond Germany’ (i.e., in East-Central Europe), these plans failed. For example, the so-called ‘Tardieu Plan’, proposed in 1932 by the French prime minister André Tardieu (1876–1945), set out ideas for a preferential tariff system in the region, but did not generate much enthusiasm in the relevant states. It ultimately came to nothing. In a sense, the states in the cordon sanitaire—the row of small states along the western borders of the Soviet Union—were further away from France and Britain than their overseas colonies.

Whether as a democratic republic or an authoritarian dictatorship, Germany was the economic centre of gravity for the states of South-East Europe, even after it became clear that the Nazi New Order was a lethal vortex for them. The pro-German part of their public understood these Nazi plans as a ‘New Europe’.

Post-1945

In the years immediately after the Second World War, all European nation-states were working to rebuild their economies, people’s livelihoods, and institutions for social welfare. As for the states of the so-called cordon sanitaire—for the moment, a few of them disappeared from the European scene. Although the immediate reason for their disappearance was German aggression, after the Second World War these states could not ignore the fact that the alliances that had been offered to them by Western powers had not been serious propositions. This is important in order to understand the more-or-less publicly expressed post-war scepticism of the idea of a unified Europe within these states.

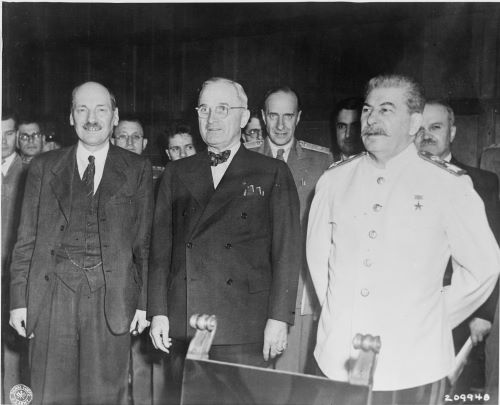

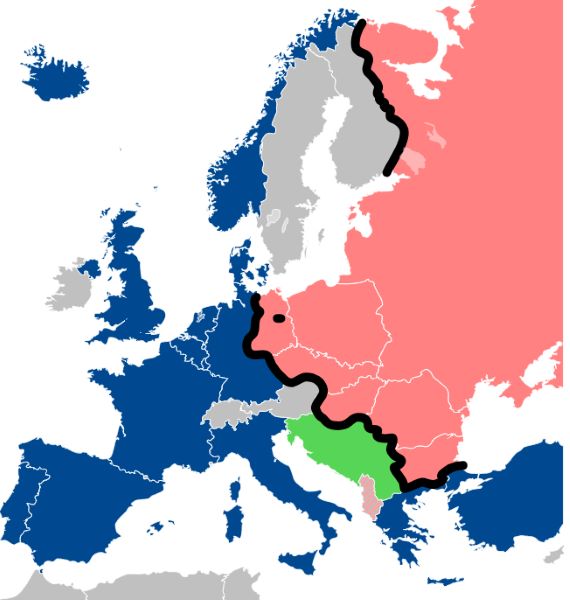

During the Cold War, Europe as an idea was primarily associated with the defence of democracy and liberty from the powers behind the ‘Iron Curtain’. The United States took the lead in reorganising Europe—for example, through the conditions of mutual cooperation that were attached to American aid funds for the European Recovery Program (commonly referred to as the Marshall Plan). In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, the Soviet Union also had plans to extend its influence further into Europe, hoping that an impoverished Germany could be drawn into its sphere of influence. With the 1948 currency reform in the three western occupation zones of Germany which stabilised their economy, these Soviet hopes were dashed. However, the Soviet Union tightened its grip on the satellite states in East-Central Europe, imposing communist regimes on them. With this region behind the Iron Curtain, out of reach, ‘Europe’ was limited to the West, and the East was considered lost. This was felt very keenly by the Hungarians who received only humanitarian (but not political or military) help from NATO during the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.

In the West, although the issue of European identity was not yet at the forefront, the European idea blossomed once again in the post-1945 period—just as it had after the First World War, inspired by visions of a peaceful and prosperous continent. Various movements on the national (as well as the international) level advocated for the establishment of a united Europe, to promote both peace and socioeconomic prosperity in an increasingly interconnected world. However, this multitude of European advocacy groups was very divided on how to approach a more united Europe. While federalist groups—most prominently the Union Européenne des Fédéralistes (UEF)—were strongly in favour of a European federal state (and a European constitution), other groups such as the ‘Unionists’ opted for more careful approaches to European integration, favouring a union of nation states over the creation of common European institutions and rules.

These post-war ideas of Europe were often promoted by prominent individuals and public figures, such as the Italian politician Altiero Spinelli (1907–1986), who supported the federalist cause, or the British politician Winston Churchill (1874–1965), who was leaning towards the Unionists. Post-war concepts of Europe were also embedded in existing international institutions and organisations. The unification of Europe was one element of a wider effort to establish a new, post-war order. Security issues, especially in the context of an intensifying Cold War, were also addressed within the context of NATO and the transatlantic community. Economic and social integration were central tasks of the Marshall Plan’s institutions and international organisations such as the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC, later OECD), the International Labour Organization, and even the United Nations and its subsidiaries.

The post-war years thus featured a great variety of European ideas that circulated within countless organisations, parties, and civic movements aiming to create a stable, prosperous, and peaceful Europe in an increasingly global world. The establishment of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in 1951–1952 and the signing of the Treaty of Rome in 1957–1958—which created the initial, six-member European Community (EC)—was one venture among many aiming to implement these ideas in the context of new political and socioeconomic institutions and common sets of rules.

For those who lived in the eastern part of the continent, behind the Iron Curtain, the notion of ‘Europe’ arose in the concept of ‘East-Central Europe’. The term first appeared in history texts, and referred to the row of states from Finland in the north to Greece in the south that had previously formed the cordon sanitaire. The notion of ‘East-Central Europe’, looking westward, expressed distance between the satellite states of that region and the Soviet Union. Hence, the term carried a certain political valence, and its usage showed that there were efforts to speak out from within the severely restricted public spheres of the Eastern Bloc.

The end of the Cold War reinvigorated the European idea. For those to the East of the fallen Iron Curtain, Europe was identified again with ‘the West’, a concept originating in the idea of the Occident, but without its Christian connotations. In 1983, during the final phase of the Communist Bloc, as its crisis became more and more evident, a new interpretation of the idea of Central Europe was proposed by the Czech writer Milan Kundera. In his article ‘The Stolen West or the Tragedy of Central Europe’, Kundera argued that Eastern Europe should return to where, according to him, it had always been—the ‘West’. The Hungarian-born British historian László Péter has argued that this idea of Eastern Europe as an integral part of ‘the West’ may—at least partly—have been a misunderstanding. Research shows that the accelerating relative deterioration of everyday living conditions in the 1980s was a central driver for change in Eastern Europe. Joining the EC seemed to offer an alternative possibility, which made Europe and European integration of the East an attractive goal for many social groups and organisations demanding change (even if these groups neither shared, nor were actually offered, all of the ideals that Western Europe publicly attributed to its union—such as democracy, a common culture, economic unity and prosperity, solidarity, subsidiarity, freedom of movement and rule of law). Furthermore, Western European governments had a broad agenda that went beyond these concerns. While uniting the continent politically and creating a stronger economic union was a paramount goal, there were also geostrategic and security-oriented reasons for integration, such as limiting Russian influence.

Another important phenomenon of the post-Cold War period was the fact that the European idea, promoted since the beginning of the twentieth century primarily by the continent’s elites, became an important issue for European public discourse, as shown by the debates on the Maastricht Treaty (1992–1993) and the treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe (2004–2005). The European idea became an important subject of debate. This debate often centred on a particular institutionalisation of the European idea, which was often considered too bureaucratic and not democratic enough. Much progress had been made in the fields of the Europeanisation of education, free movement, and even social benefits—through, for example, the Erasmus scheme for student mobility, the Bologna Process, and the introduction of the European healthcare card. Still, the idea of Europe—or rather the EU—also became identified with overly bureaucratic institutions, weak democratic participation, and insufficient political representation for its citizens. Recurring crises, such as the global financial crisis of 2008, and—more importantly—the failure of the EU member states to adequately respond to them with one voice and in solidarity, have aggravated preexisting anti-European sentiments across diverse social strata and political parties in Europe. The current steep rise of anti-Europeanism is therefore one of the major challenges to the European idea at present.

Conclusion

Arguably, the idea of Europe was never tested as it was during the twentieth century, a time when the continent was devastated by unprecedented violence and bloodshed, driven by ideological divisions, and divided between two superpowers locked in a seemingly endless stand-off. At the same time, by the end of the century, the idea of a united, peaceful, and prosperous Europe had become an everyday experience for most people on the continent. These two extremes characterise the development of ideas of Europe in the twentieth century. Throughout the crises of the first half of the century, when the reality of a united Europe seemed further away than ever, the idea of Europe was proposed as the solution to the continent’s upheavals, as a common goal in peace and prosperity.

After 1945, this vision of European unity was limited mostly to Western Europe and framed by the ideological struggle between East and West. When this vision was put into practice, under American guidance, it lost some of its allure through the evidently bureaucratic nature and undemocratic ethos of European institutions. However, when the Cold War ended, the reality and idea of Europe, embodied for many by the supranational institutions of the European Union, seemed stronger than ever, and the natural model for the whole continent. Since then, the lived idea of a united Europe has lost some of its sheen, weathering internal and external crises, and has had to face growing criticism by anti-European movements.

Suggested Reading

- Bruneteau, Bernard, Histoire de l’idée européenne au premier XXe siècle à travers les textes (Paris: Armand Colin, 2006).

- Conze, Vanessa, Das Europa der Deutschen: Ideen von Europa in Deutschland zwischen Reichstradition und Westorientierung, 1920–1970 (Berlin and Boston: Oldenbourg, 2005).

- Du Réau, Élisabeth, L‘idée d‘Europe au XXe siècle: des mythes aux réalités (Brussels: Complexe, 2008).

- Morgan, Glyn, The Idea of a European Superstate: Public Justification and European Integration (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005).

- Patel, Kiran Klaus, Project Europe: A History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020).

- Péter, László, Miért éppen az Elbánál hasadt szét Európa? [Why was Europe split right along the Elbe?], in László Péter, Az Elbától keletre: Tanulmányok a magyar és kelet-európai történelemből [East of the Elbe: Studies on Hungarian and East European History] (Budapest: Osiris, 1998).

- Soubigou, Alain, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (Paris: Fayard, 2002).

- Tomka, Béla, A Social History of Twentieth-Century Europe (London: Routledge, 2013).

- Van der Wee, Herman, Prosperity and Upheaval: The World Economy, 1945–1980, (Harmondsworth: Viking, 1986).

- Wolff, Larry, Woodrow Wilson and the Reimagining of Eastern Europe (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2020).

Chapter 1.1.1: Ideas of Europe in Early Modern History (ca. 1500–1800), from The European Experience: A Multi-Perspective History of Modern Europe, 1500–2000, published by Open Book Publishers (02.06.2023) under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.