Knowledge of the functional foci of the gods was of paramount importance.

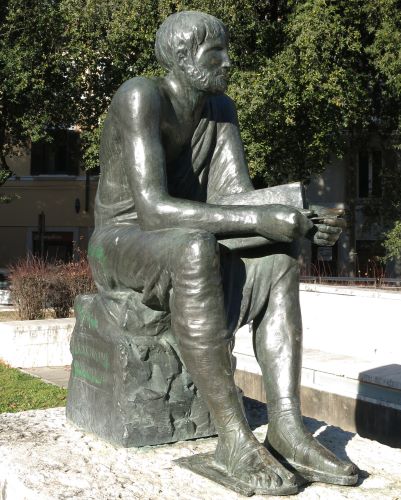

By Dr. Michael Lipka

Professor of Religious Studies

University of Patras

Divine concepts were commonly related to specific functional spheres. I shall use the word ‘functions’ here in the narrow sense of ‘functions within the polytheistic system’. The dissolution of the world into spheres of power and the attribution of these spheres to divine concepts, thus rendering them ‘functions’ of a god, is a fundamental characteristic of all polytheistic systems. Polytheism would be senseless if divine functions were not divided.

Spheres of divine functions were conceptualized according to the principle of functional similarity. By this I mean, for instance, the fact that it hardly mattered whether the Romans campaigned against the Sabines or the Persians: the common denominator of both actions was the functional focus of ‘war’, traditionally attributed to the divine concepts of Mars and Iuppiter. Nor did it matter what specific ailment had to be cured: diseases belonged to the realm of Apollo Medicus and later on to Aesculapius.

Knowledge of the functional foci of the gods was of paramount importance. One of Varro’s objectives in his Divine Antiquities is to spell out the functional foci of individual Roman gods, “for it is on the basis of this that we can know which god we ought to call upon or invoke for each purpose, lest we should act like clowns in a mime-play and ask Liber for water and the lymphs for wine.”277 The concept of Liber was formed according to a group of similar functions linked by the concept of ‘wine’, while the concept of lymphs was formed according to a group of similar functions linked by the concept of ‘water’. The functional scope of either deity was, however, not invariably fixed, but accommodated to the relevant context. Thus, lymphae (= nymphae), when used alone, might denote both the divine and real aspect of ‘water’, whereas it denoted only the divine aspect (= ‘water deity’) when worshipped in connection with ‘springs’ (fontes).278 By contrast, Liber was not only the god of ‘wine’, but, in a festival on October 15, also more specifically the god of ‘vintage’.279 Given the possibility of developing the functional scope of a divine concept on the principle of functional similarity in various directions, it is more correct to speak of ‘water’ and ‘wine’ here as functional foci than ‘functions’.

Functional foci of divine concepts were determined by four parameters: tradition, readjustment, analogy and etymology. All four parameters contributed to the realm of functions of a deity, and since the former are not static, the latter is not either:

- By tradition I refer to the (rare) fact that the functional foci of a few gods in the Roman pantheon appear to continue corresponding foci of a tradition that reaches back to prehistorical/Indo-European times. Iuppiter ‘ruled’ over the sky, since he was the direct descendant of the Indo-European sky god. In the same vein, Castor and Pollux were in charge of horse-breeding and rescuing (e.g. as patrons of sailors) just like their Indo-European forefathers. Mithras does not belong here. Though apparently an Indo-European divine concept, he was unknown in Rome until the end of the first century A.D. and was apparently, albeit inspired by Persian influence, created more or less from scratch as a mystery deity by his new western adherents.280

- By readjustment I mean that the Roman priestly élite was always keen to readjust the functional foci of a god, in order to better or defend its own cause against an encroachment by other cults or politics in gen-eral. Naturally, such readjustments were hardly ever voiced in public, and the process of readjustment is thus scarcely traceable directly in the sources. Two possible cases are the identification of Quirinus with Romulus after the former’s subjugation to Mars and the assimilation of Iuppiter Dolichenus and his spouse, Iuno Dolichena, with Sarapis and Isis, as described above.281

- By analogy I mean the fact that functional foci can be modified or created on the analogy of the functional foci of other gods. Normally, this process is linked to the full or partial identification of the gods in question. From the earliest Roman literature, examples abound of identifications of major Roman gods with Greek—later on also with Egyptian, Syrian and Persian—deities.282 For instance, Iuno’s functional focus as the Roman goddess of marriage par excellence was, no doubt, either created or strongly promoted by her identification with Hera as the spouse of Iuppiter/Zeus. In poetry, Liber became more or less exclusively the wine-god after identification with Greek Dionysos; and Mercury, as his name suggests (merx = commodity), was initially a god of commerce, before the identification with Hermes made him the god of arts (‘inventor of the lyre’) and messenger of the gods. His subsequent identification with the Egyptian Thot added the notions of magic, astrology and writing.

- By etymology I mean that functional foci were based on real or imagined etymological links between divine proper names and Latin appellatives.283 Such a link is most apparent in the case of deified abstract nouns. For instance, Tellus’ functional sphere is ‘earth’, for that is what the word means in Latin. But such clear-cut cases are comparatively rare. Normally, divine proper names are not attested as self-contained appellatives in the Latin vocabulary. Nevertheless, ancient scholars such as Varro, or popular wit, never ceased to ‘etymologize’ divine names. Where such etymologies hit the truth, they could, on occasion, recover functions forgotten in the course of time. However, where they did not, a basically irrelevant Latin appellative automatically led to a new functional focus of the deity.

As a rule, it was not only etymology that determined the functional focus or foci of a god. Rather, etymology was supplemented by tradition, readjustment and analogy, as I have mentioned above. Sometimes, though, divine competence was exclusively determined by etymology. Modern scholars have dubbed these divine concepts ‘functional gods’, because they were seemingly named after their functional foci. In a large number of cases, these etymologies, although widely and will-ingly accepted by ancient writers, were definitely wrong in historical terms.284 However, it is important to note that in conceptual terms a flawed etymology is as important as a correct one, as long as its validity was recognized by the Romans themselves.

Many ‘functional’ gods had a significant role to play in the private sphere. However, some appear in public cult, too. For example, Fabius Pictor, as quoted by Servius,285 mentioned a sacrifice to Tellus and Ceres, performed by the flamen Cerialis, in the course of which twelve deities were invoked. The deities who were summoned represented deified aspects of agricultural labour: the god ‘that breaks up the soil’ (Vervactor), ‘restores’ (Reparator), ‘forms land into ridges by ploughing’ (Imporcitor), ‘grafts trees’ (Insitor) etc. The fact that all these functional deities were male, while the two deities receiving the sacrifice were female, clearly indicates that the former were gods in their own right (and not just functional sub-categories of the two main goddesses Tellus and Ceres). The observation that all these functional deities conform to the rules of Latin derivatives in ‘-tor’ (nomina agentis) also demonstrates how close these divine proper names still were to mere appellatives.286 In a similar vein, one may refer to Adolenda, Commolenda, Deferunda and Coin-quenda (four ‘functional goddesses’ of the same formative type and, no doubt, derived from actual appellatives), who were worshipped—in the official cult—by the arvals.287

Given the sheer numbers of potential gods with their various functional foci and the fact that some of these gods were important to the public domain too, it does not come as a surprise that the pontiffs tried to catalogue and standardize the various gods along with their specific functions. The result was the so-called indigitamenta. These were manuals of some sort for pontifical use, specifying the nature of various gods to be invoked on cultic occasions as well as the sequence in which this had to be done. The one (almost) certain fact about such lists or handbooks is that Varro, in the 14th book of his Antiquitates Rerum Divinarum, made extensive use of them. He thus became the principal, if not the only, mediator of their contents.288

Scheid has recently doubted the priestly authorship of such written documents.289 He argued for a twofold oral tradition (ritual calendar/precise instructions for the offices), but granted that there were booklets (libelli) “for the recitation of speci c prayers and hymns”.290 He also admitted that there was a tradition of lay scholars reaching back at least to the fourth century B.C., who “commented” on such oral tradition.291 On closer inspection, this distinction between lay scholars and priests is elusive: although it is, of course, impossible to trace back the authorship of documents of religious relevance such as the indigitamenta to specific authors, the group most interested in, and most likely responsible for, their composition and subsequent preservation was no doubt the pontifical college. It is irrelevant whether the pontiffs themselves composed these works as pontiffs or as lay scholars, or whether the job was done by someone else. The point is that the existence of such documents allowed in a most unprecedented way for the preservation of anachronistic and complex ritual knowledge, access to which was limited to members of the college and potentially to those few others who possessed the relevant expertise. Following the great French scholar here would mean—to take a similar example—ignoring the enormous impact of the Sibylline oracles on the religious history of Rome on the grounds that their actual composers were most likely Greek poetasters rather than Roman priests.

The fixing in writing of the indigitamenta forms a landmark in the history of Roman polytheism, whoever its actual author may have been. The introduction of a ‘fixed’ canon of functionally specified gods led automatically to a fixation of the pantheon in functional terms. The reason for the compilation may have been technical, but ultimately this instrument meant a tremendous increase of power for the pontiffs who were in charge and—what is more—had control of it.292 Although it would certainly be wrong to assume that Roman polytheism ever stopped producing (or simply ‘naming’) new gods on functional grounds,293 the indigitamenta provided the means to preserve the names and functions of gods who had long been forgotten as well as control the inclusion of new gods.

There is no fixed date for the composition of the indigitamenta. However, a passage in Arnobius may possibly help. According to him, Roman scholarly literature explicitly noted the absence of Apollo in the indigitamenta of ‘Numa Pompilius’.294 Numa, the successor of Romulus, was commonly regarded as the ‘organizer’ of Roman religion par excellence. Therefore, the Arnobian passage can only refer to the oldest indigitamenta known to Arnobius. Furthermore, the expression implicitly takes account of the fact that in a later version Apollo seems to have been included in the indigitamenta.295 Given that Apollo had received an official temple, and that means a place in the official pantheon, as early as 431 B.C., it is plausible to conjecture that the first indigitamenta known to Roman antiquarians (as known by Arnobius) predate the year 431 B.C. This is in line with North’s fine observation that the bookish nature of Roman religion was shared with Etruria and therefore may date back to the period of their mutual influence, possibly the sixth and fifth centuries B.C.296 Furthermore, the indigitamenta, and more generally the keeping of written records, may have been the actual cause of the ascent of the pontificate from an association of ‘bridge builders’ (perhaps without any particular religious notion) to that of the highest priestly college in Rome.297

Occasionally, the nature of a deity with specific functions was unknown. In this case, the Romans addressed the deity as sive deus sive dea vel. sim.298 Patron deities of foreign cities were evoked with these words299 and expiatory sacrifices were thus offered to the deities that had caused earthquakes, if their identity could not be determined more accurately.300 Equally unspecified was the patron deity of trees and groves, which is why, according to Cato, the specific formula had to be employed on trimming trees.301 In order to avoid dire consequences when omitting the names of gods, the pontiffs addressed the hitherto unnamed divine forces with the general dique deaeque omnes at the end of their invocations.302

A god could have very distinct, mutually independent functional foci. For instance, Apollo, the healing god, is functionally distinct from Apollo, the guardian of FIne art, and both aspects are entirely separate from the god’s prophetic competences. The three aspects develop independently: as a healing god Apollo remains a cipher in Rome, as protector of the arts he is the cherished subject of all poetry (though virtually without a cult), while as the source of prophecy he bulks large as the inspirer of the Sibylline books. Augustus did not hesitate to build a temple to Apollo next to his Palatine residence, because it was the Greek god of youth, art and culture, as well as his personal divine protector that he was thus honouring, not the old and unpopular healing god (who already possessed a temple in the Campus Martius). In the same vein, a ‘foreign’ deity could be adopted in different functional modes. Thus Venus Erycina was introduced to Rome from Mount Eryx in Sicily when Rome was under siege during the Hannibalic wars. As such, i.e. as a tutelary deity, she received a temple on the Capitol in 215 B.C. Meanwhile, a second temple was built to her as a fertility deity outside the Colline Gate in 181 B.C.303

The divine functional foci of the living ruler were advertised by imperial propaganda (even though there was no actual cult). Such foci sprang from his political functions within the Roman state (res publica), his foremost task being its eternal welfare (salus publica/populi Romani). As the human incarnation of the res publica, his well-being was tantamount to the well-being of the state. Cicero, for instance, established a link between Caesar’s salus and the fate of Rome in 46 B.C.304 Later, vows were made regularly on behalf of the salus of individual rulers (e.g. pro salute Augusti), no doubt as guarantors and protectors of the established order.305 In doing so, the living emperor appropriated essential functional foci of the Republican Iuppiter Optimus Maximus, irrespective of whether he was actually identiFIed with him or only worshipped like him. Consequently, within the state, the living emperor operated on two different levels, as guarantor of the order of human beings and as a mediator between human beings and gods. From Augustus’ reign onwards, both functions were expressed in the form of address of the emperor, as this is attested innumerable times in epigraphy, the former by the term imperator, the latter by the word augustus.

By contrast, a deceased emperor, though considered divine, was virtually void of functions.306 Rather, his raison d’être was to legitimate the rule of his successor. In other words, his successor’s claim to power was the major and, in principle, sole motivation for his own post-mortem deification. The pomp with which his deification was celebrated may be exemplified by the case of Pertinax: after the latter’s murder and burial in 193 A.D., one of his successors, Septimius Severus, eager to justify his claim to power, made himself an avenger of Pertinax’s killers and provided for ‘heroic honours’ in his name (heroikai timai).307 After his enthronement, Severus “erected a shrine to Pertinax, and commanded that his name be mentioned at the close of all prayers and oaths. Severus also ordered that a golden image of Pertinax be carried into the Circus on a cart drawn by elephants, and that three gilded thrones be borne into the amphitheatres in his honour.”308 Severus pompously staged Pertinax’s deification (employing a wax effigy of the dead)309 and elevated him as a god in the usual manner (spatial/temporal/personnel foci).310

Sometimes, the functional foci of two or more divine concepts coincide more or less totally. In this case, two solutions were conceivable. The competing parties might differentiate their functional foci, with the result of a redefinition and clarification of their spheres of competences. Or one of the two competitors might lose his or her identity in part or entirely. Where the latter case did not lead to a full extinction of the succumbing party, the relationship with its superior was highlighted in Latin in two fashions. Either the name of the inferior deity was simply added to that of its competitor (formally indicating a balance of powers), as this is attested in the cases of Iuppiter Summanus311 and Iuno Matuta312 and according to my earlier argument possibly Iuppiter Feretrius.313 Or else it was accompanied by the name of the latter in the partitive genitive (indicating partial functions within a larger functional whole), as in the case of Lua Saturni, Salacia Neptunis, Nerio Martis, for example (‘Lua in the sphere of Saturn’).314 In the case of the ‘god of the beginning of war’ both types are attested: Ianus Quirinus and Ianus Quirini.315 Similar, but not identical, is the addition of Augustus/Augusti to traditional gods, as is frequently found on imperial inscriptions: Hercules Augustus/Augusti is ‘Hercules in the sphere of Augustus’, i.e. Hercules in his capacity as protector of the ruling emperor. In the same vein, we find, for instance, a Silvanus Flaviorum, who receives a dedication by a Flavian freedman.316 The difference to the former cases of succumbent gods is that the ruling emperor was presumably not normally felt to be a divine entity in these contexts.317

I shall now discuss some alternatives of functional interaction by means of three test cases, Apollo—Aesculapius, Summanus—Iuppiter, and Mater Matuta—Carmenta—Iuno.

1. Suppression of functional foci could go hand in hand with the reinforcement of other functional foci and therefore lead to an overall redefinition of the god’s sphere of competences. A case in point is Apollo, who may have had similar functions as his Greek pendant in early Rome, but whose functional focus of ‘healing’ was particularly emphasized by the dedication of a temple to Apollo the Healer (medicus) in the mid-fifth century B.C. Over time, this functional focus faded into oblivion, and Apollo increasingly became the Roman god of Greek art and culture par excellence, while ceding his healing competences to Aesculapius, another Greek import. To illustrate this development, I will recapitulate briefly the history of the two cults.

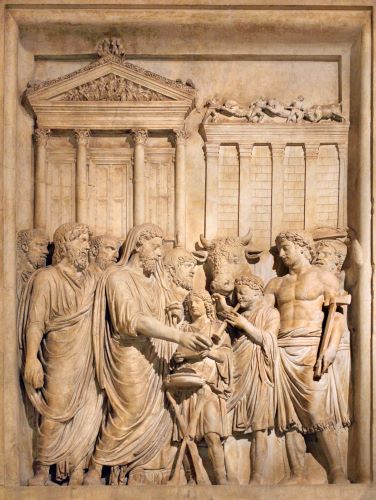

In 449 B.C., Livy mentions a precinct of Apollo (Apollinare) outside the city walls, close to the Porta Carmentalis. After an epidemic, a temple to Apollo the Healer (medicus) was erected on the site in 431.318 The location can be explained by the fact that illness, like death, had no place inside the city walls. Apollo’s epithet, the occasion on which his temple was built, and its extramural location, make it unmistakeably clear that the cult focused on the god’s ‘healing’ competences. On the other hand, there is no indication that the god was in any way connected with other aspects dominant in the corresponding Greek cult, most notably oracular functions. Indeed, quite the opposite is the case, as the Sibylline books were kept in the Capitoline sanctuary of Iuppiter rather than in the temple of Apollo, as would be expected. Even when the old books were destroyed in the fire of 83 B.C., the newly compiled collection was again stored in the Capitoline temple when it was rebuilt.319 It was not until the time of Augustus that the collection was possibly transferred, not to the old sanctuary of Apollo the Healer at the foot of the Capitol, but to the new Palatine temple of Apollo.320 Not before 37 B.C. and under Augustan patronage did the god find his way on to Roman coinage, but this time in his capacity as the Greek oracular god (in fact, only his tripod was depicted).321

The Palatine temple was dedicated by Augustus in 28 B.C. It was built of white Luna marble and lavishly decorated with pieces of Greek sculpture, executed with “unique munificence”.322 The group of cult statues venerated there (Apollo, Diana and Latona) were the work of famous Greek artists.323 It had a library attached to it, and played a dominant role in the Secular Games of 17 B.C. It was also a place of assembly for the senate.324 Architecturally, it was connected to Augus-tus’ residence via corridors. In short, it was designed to be what the old temple of Apollo was not: a spatial focus of an exclusively Greek god, who happened to be also the guarantor of the well-being of the emperor and the Empire.

This is not to say that the Romans were ignorant of major functional foci of Greek Apollo before the Augustan period. In fact, the god’s functional position in the Greek pantheon had always been known and partly adopted in Rome. For instance, it was Greek myth that established a kinship link between Apollo, Latona (his mother), and Diana (his sister) and it is therefore no coincidence that the triad was worshipped (along with Hercules, Mercury and Neptune) at the first lectisternium in 399 B.C.325 The Games of Apollo (ludi Apollinares) in 212 B.C. and later were held according to “Greek custom” (Graeco ritu)326 and involved scenic performances according to similar Greek practice.327 By the middle of the first century B.C., the Sibylline books became linked with Apollo, evidently under Greek influence. However, as I have mentioned above, they had no verifiable impact upon the Roman cult of Apollo until their transference to the Palatine temple under Augustus.328 The old temple of Apollo was adorned with various famous pieces of Greek art, set up on completion of restoration work in the thirties or twenties B.C.329

Despite his undoubtedly central and well-defined functional focus as healing god, Apollo never became popular in Rome.330 In marked contrast, Aesculapius, whose temple like that of Apollo was also dedicated after an epidemic in 290 B.C. and outside the city wall (i.e. on the Island in the Tiber) enjoyed private worship from an early date. This is attested by a number of dedicatory inscriptions, the earliest of which belong to the third or second century B.C.,331 as well as an impressive number of votive terracottas.332 The temple could provide funds for long-term building projects.333 It was frequented not only by the poor, but also by the well-off. For example, Cicero’s wife Terentia seems to have been a regular visitor.334 This is even more astonishing, given that the cult did not command attention in other parts of central Italy, with the notable exception of Fregellae, where, however, it may have continued an indigenous cult.335 Nor did it receive particular sup-port from the Julio-Claudian emperors.336 Only from the Flavian period onwards was the cult of Aesculapius increasingly instrumentalized for political ends.337

The success of Aesculapius as a healing god in Rome no doubt accelerated the process of ‘hellenization’ of Apollo, i.e. the shifting and extension of the functional foci of the Roman god towards the corresponding foci of his Greek counterpart. At the conclusion of this process of redefinition stands the Palatine Apollo. This ‘Augustan’ Apollo apparently possessed all functional foci of the Greek Apollo, with one exception—his healing competences. Ovid seems to have been aware of the competition between Aesculapius and Apollo, since he tries to reconcile both, making Aesculapius not arrive from Epidauros until he had secured the explicit approval of Apollo, his “father”.338

2. Varro, referring to ancient sources (annales),339 represents Titus Tatius, the Sabine king, as the founder of an altar to Summanus.340 Although no such altar is archaeologically attested in Rome, during the Republican period we do find a terracotta statue of the god on the roof of the Capitoline temple.341 It is a quali ed guess that the supposed altar stood in the precincts of the Capitoline temple, and that its cult was integrated into the complex in a manner similar to the cults of Iuventus and Terminus.342 A decision to dedicate the original altar on the Capitol, one of the highest spots in the city, can be explained by Summanus’ functional focus as a god of lightning, which is also reflected in his very name, “the highest”.343 However, in the Roman pantheon this functional focus was already occupied by Iuppiter. A solution to this dilemma was to subordinate Summanus to Iuppiter and to refer to him simply by means of an epithet, as is done on two inscriptions from northern Italy, where he appears as Iuppiter summanus,344 and by the epitomes of Livy’s book XIV (reflecting Livian word usage?), which refer to Summanus simply as Iuppiter. The other, more widely accepted, solution was to adopt Summanus as an independent entity into the Roman pantheon, though with limited and specified functional foci. He became, perhaps under Etruscan influence, the god of nocturnal lightning, handing over his métier of diurnal lightning to Iuppiter.345 Even a new etymology was invented, which made him the god “before morning” (*sub-manus) in accordance with his new nocturnal competences.346 In the course of time, the original aspect of a god of “height” was lost too, with the result that in the third century B.C. a temple to him was erected, not on a hill-top, but somewhere in the valley between the Palatine and Aventine, “not far away from the carceres of the Circus Maximus”.347 Finally, after his relegation to night-time and darkness, Summanus eventually appears as a god of the underworld from the third century A.D. on.348 A truly remarkable career.

To some extent, a parallel is offered by the antagonism between Apollo and Sol. In its form of Sol Indiges, the latter was apparently an age-old Roman deity, whose functional sphere came to overlap with that of Greek Apollo as an identification of the ‘sun’, when the latter identification became prominent in Rome in the Augustan period. As Summanus adorned the roof of the temple of Iuppiter but lost most of its functions, so Sol’s chariot was exhibited on top of Apollo’s Palatine temple built by Augustus,349 paying homage to the older and waning deity. Befittingly, Horace did not fail to turn to Sol in his Carmen Saeculare, which was actually a hymn to Apollo and his sister performed on the occasion of the Secular Games in 17 B.C. in front of the god’s Palatine temple.

My notion of Summanus as an originally independent god who was eventually suppressed by Iuppiter is not uncontroversial. Thus, Wissowa and others considered Summanus to be a Jovian hypostasis, denoting a god of night-time lightning who had become emancipated from Iuppiter in his shape as the sky god.350 However, such a course of reasoning runs into serious difficulties. The third-century B.C. temple of the god was erected in the vicinity of the Circus Maximus, which was a fair distance from both the Capitoline sanctuary (where most Jovian hypostases had their temples)351 and the temple of Iuppiter Fulgur in the Campus Martius, the direct functional counterpart to Summanus.352 The anniversary of the temple ( June 20) was not linked to any specific Jovian day, nor to the foundation of the temple of Iuppiter Fulgur (October 7) for that matter. Besides, its closeness to the summer solstice would be surprising in the case of a god who operated exclusively at night. Furthermore, a terracotta statue on top of a temple would be as unparallelled a beginning for a future hypostasis, as would be the distinction of various forms of lightning outside the Etruscan discipline. Last but not least, Varro points to Summanus’ popularity before the installation of the Capitoline triad, suggesting a subsequent decline in popularity rather than an increase. However, only rising popularity would justify an emancipation.353 On balance, it is safer to claim that, in historical times, Summanus was an independent god in decline, not an increasingly powerful aspect of Iuppiter that eventually became emancipated from the old sky god.

3. The cult of Mater Matuta in the Forum Boarium dates back to the archaic period, as is evidenced by a seventh-century votive deposit and a sixth-century temple discovered in the region as well as the annual festival of Matralia, already mentioned in the earliest known feriale. It had its pendant in the archaic cult of the same goddess in Satricum, some 60 kilometers or so south of Rome.354 Regarding the question of functional foci of Roman Mater Matuta, it is irrelevant whether matuta can be linked etymologically to matutinus (“belonging the morning”) or manus (“good”) or both.355 Neither etymology would have been evident to an ordinary Roman. Indeed, neither is markedly present in the actual rites of the cult, as far as we can reconstruct them. It is however important to note that in the old calendar, the festival of the goddess is simply called Matralia, i.e. “festival of mothers”, without further specification. Despite various fanciful interpretations, the most straightforward solution would seem that the underlying word mater here was used in a general sense for matrona. In other words, the Matralia were the old festival of the free, Roman housewife, in charge of the children as well as the household, and all things connected with the family, including childbirth.356 Such an approach explains the little we know about the ritual from later sources, viz. the fact that only women who had been married once (univirae) could perform the cult,357 while slave-women were excluded. Once a year a slave-woman was symbolically driven out of the temple while receiving a beating.358 A strange rite of embracing one’s nephews and nieces and praying for them, instead of one’s own children, was presumably a remnant of an originally much larger ritual context. Whatever its nature, it appears to have been strongly connected with the notion of family and blood-kinship.359

The reason why Mater Matuta eventually attained only a marginal position in the pantheon of Republican Rome appears to have been the very similar functional foci of Iuno, who rose unchallenged as the female goddess par excellence after the inauguration of the Capitoline triad towards the end of the sixth century. Whatever her prior position in the Roman pantheon, Iuno’s importance can only have been considerably strengthened by this event. It was not only as a member of the most powerful divine triad that Iuno superseded other female patron god-desses. Later, the festival of Matronalia on March 1 was dedicated to her, which therefore competed with the Matralia of Mater Matuta.360 The merger of both deities is attested by Livy, who mentions Iuno Matuta on one occasion (perhaps actually referring to Iuno Sospita).361

A similar ‘victim’ superseded by the spread of Iuno’s cult was Car-menta (also referred to as Carmentis), whose temple was located virtually next to the temple of Mater Matuta and possibly complemented it in ritual terms.362 According to Varro, Carmenta was an old goddess of childbirth.363 If so, she must have been subordinated to Iuno (Lucina) at an early stage.364 Her antiquity and importance are guaranteed by her ancient sanctuary and by the fact that she had her own flamen and a festival (Carmentalia).365 The age of the sanctuary is vouched for, not only by the supposed connection of the cult with Euander,366 but also by the existence of the Porta Carmentalis, which took its name from the sanctuary nearby.

The three test cases, Apollo—Aesculapius, Summanus—Iuppiter and Mater Matuta—Carmenta—Iuno show some general characteristics of functional interaction. To begin with, in all three instances functional foci shifted. The moving force of this vibrating system of functional foci was the attempt to avoid functional overlaps. Although the whole system was highly fluid, there was a clear tendency to have each functional focus occupied by one, and one only, divine concept at a time. While it is thus fair to say that functional foci were oscillating according to historic circumstances, the overarching principle of economy is omnipresent: ideally, each functional focus belonged to one god only.

Second, the expansion of the functional focus of a divine concept necessarily led to restriction of the functional foci of another, if a functional overlap was to be avoided. On the part of the divine concept under attack, this led to either extinction or modification. Modification meant dissolution of a functional focus into a number of constituent functional foci and the ceding of part of these new constituent foci to the expanding deity. Thus, when encroached upon by Iuppiter, the functional focus of ‘lightning’ of Summanus was dissolved into ‘day lightning’ and ‘night lightning’ and the former was ceded to Iuppiter. On the other hand, the expansion of the functional foci of Iuppiter was again based on the principle of functional similarity, for both ‘blue sky’ and ‘lightning’ resembled each other in that both were meteorological phenomena. Both expansion and restriction of functional foci were actually governed by the same principle of similarity.

Third, old concepts died hard. Since the privileged nature of divine concepts was normally neatly tied up with patterns of power within society, it was expedient to abandon these concepts only in the very specific case of revolution, i.e. a violent redistribution of power within society. But this case was exceedingly rare, and normally divine concepts did not serve to propagate the new, but to cement and corroborate the old. This is why divine concepts such as Summanus, Mater Matuta or Carmenta were not abolished but redefined or left untouched, even at the cost of violating the principle of functional economy described above.

The welter of innumerable gods, with practically innumerable functional foci, made Roman polytheism in its entirety a cumbersome instrument for fulfilling the religious needs of the ordinary people. The answer to such a problem was selectivity. Selectivity meant that the whole range of potential functions was projected on to a very limited number of gods. Selectivity was the precondition that would make private cult work, although it stood in stark ideological contrast to the official pontifical religion. Selectivity meant ascribing privilege to a few gods as opposed to the many, and significantly expanding the functional foci of the privileged deities at the cost of those gods excluded. The climax of this development was the adherence to virtually one single god among the many. This phenomenon is now widely known as ‘henotheism’, a term introduced by Versnel’s classic study ‘Ter Unus’ less than two decades ago.367

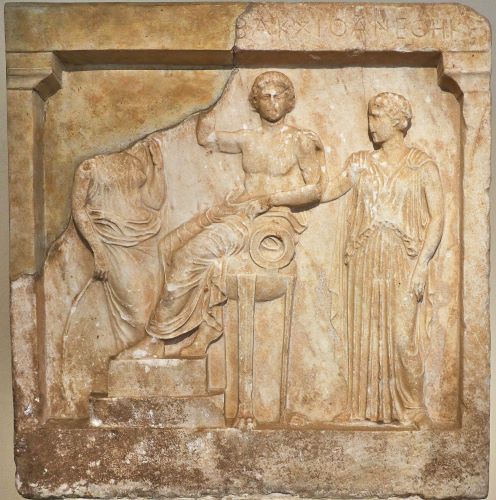

Selectivity was no doubt inherent in Roman polytheism from time immemorial. The first example on record is the cult of Bacchus, eventually banned by the senate in 186 B.C. Livy and the Tiriolo decree testify to the degree of exclusivity which this cult implied by imposing a specific lifestyle, as well as to the exceptional devotion of its followers. They suggest that Bacchus was considered, if not the only god, at least the only god that mattered, and the indisputable head of the pantheon at least in the mind of those who followed him.

It was selectivity that opened the door to foreign cults and ensured their success. A prime example is the cult of Isis. In Rome she appears in two forms, as goddess of the sea (Isis Pelagia, Pharia) with a specific festival, the Isidis navigium, on March 5, 368 and as goddess of fertility and agriculture (Isis Frugifera).369 But in the eyes of her adherents, her competences were much wider. Apuleius lets her describe herself as “mother of the universe, mistress of all the elements, first offspring of the ages, mightiest of deities, queen of the dead, foremost of heavenly beings, uniform manifestation of all gods and goddesses etc.”370 Elsewhere he speaks of her as the one “that gives birth to all”, “that rules over everything”, or “the mother of all time”.371 A Greek inscription from imperial Rome refers to her as the goddess “that surveys every-thing”.372 In other inscriptions from Rome she carries the title “queen” (regina),373 and she is identified with Iuno in Rome in the late second century A.D.374

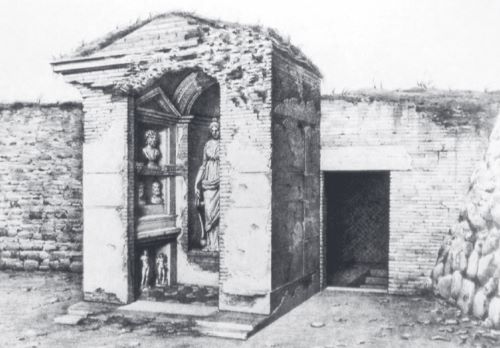

From the time of Franz Cumont, scholars have been in the habit of connecting Christianity with the cults of other oriental deities such as Isis and Mithras to explain the decline of the traditional Roman pantheon. However, Christianity differed fundamentally from these oriental religions in one particular point: its functional exclusiveness. For other oriental gods never precluded the existence of competing divine forces. At most, the latter were considered emanations of the central divine power. One may refer to Isis again: as we have just seen, in her most extreme form the goddess was conceptualized as embodying competences of all the members of the Roman pantheon, of which however she remained an integral part. Her inclusive functional force is documented, for instance, by a Roman dedicatory inscription from 1 A.D., where she appears between Ops and Pietas following a series of ten or eleven traditional Roman gods.375 In representational art, her functions are manifest in manifold syncretistic iconographic forms (see below on iconography)376 and in peculiar bronze figurines from the second century A.D. In these figurines, major gods of the Roman pantheon (including Isis) are represented by their characteristic attributes (signa panthea).377 Finally, one may point to an aedicula (lararium/shrine?), discovered on the Esquiline in a domestic context dating from the era of Constantine: a statue of Isis of considerable size (height 1.50 m) was placed in the central niche of the aedicula. Isis appeared here as Isis-Fortuna, combining icongraphic requisites of both the Egyptian deity (uraei, basileion) and the Roman goddess (steering oar, cornucopia). Although she clearly occupied the central position, marked by both the central place and size of the statue, she was also flanked by statuettes and busts of other Roman and Egyptian deities (figs. 1 a, b).378 Even more, the aedicula was placed next to a door which led to a Mithraeum. It has been argued convincingly that both sanctuaries were functionally connected. Perhaps the Mithraeum was destined for the male, the Iseum for the female occupants of the house.379

The reason why no other oriental deity (apart from the Jewish and Christian gods) ever detached itself from the notion of functional plurality is, of course, historical: all other oriental gods that played any significant role in the Roman pantheon hailed from polytheistic systems. There was, then, neither need nor opportunity to change their poly-theistic profile in terms of functions, when they entered the Roman pantheon. Once more, the case of Isis affords a classic example of the importance of the historical dimension. Emerging from the multifarious Egyptian pantheon, Isis became part and parcel of various local Greek panthea and as such entered Rome as one constituent of a larger polytheistic whole. By contrast, the exclusive nature of the Christian god is manifest by its very namelessness: while all other gods of the pagan pantheon, including the so-called oriental deities, were addressed with their name or, at least, a substitute for it (e.g. Bona Dea), the Christian god, like his Jewish precedent, was referred to simply as ‘god’ by his worshippers.

The exclusive attribution of all functions to a single divine concept had another side to it, which was to eventually favor the spread of Christianity quite significantly. The Christian and Jewish gods could easily be transferred from one place to another without any modification of functional foci. While it was always possible to export a god of any polytheistic system in the same way, such a move could not be completed without assimilating the migrant deity to its new polytheistic environment, because the functional foci of the latter were not self- sufficient, but dependent on the divine ‘constellations’ of the polytheistic system surrounding it. Theoretically, it was a comparatively easy task to introduce, for instance, the cult of Iuppiter Optimus Maximus to the market places of Roman colonies. However, the outcome of this transfer was not the Roman Iuppiter Optimus Maximus. Rather, the migrant Iuppiter was normally either assimilated to prominent local deities or remained an outsider, constituting an additional functional focus, i.e. that of ‘Romanity’. The homogeneity of functional foci of the Christian and Jewish gods throughout the ancient world could thus never be achieved by any god hailing from a polytheistic system. In short, the Christian and Jewish gods were basically the only truly international divine concepts in the ancient world in functional terms.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Chapter 1.4 (66-88) from Roman Gods: A Conceptual Approach, by Michael Lipka (Brill, 04.30.2009), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license.