A reminder that democratic participation has historically taken forms that blurred the boundaries between politics, social life, and personal risk.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Gambling on the Republic

From the nation’s founding through the early twentieth century, betting on elections occupied a conspicuous and culturally accepted place in American political life. Far from being a fringe indulgence, wagering functioned as a visible and participatory means of engaging with electoral uncertainty. Citizens staked money, property, labor, and reputation on outcomes that mattered deeply to their communities, transforming elections from abstract contests into lived experiences of risk and consequence. In a political culture that prized public participation and face-to-face judgment, betting became one way Americans expressed confidence in their candidates and convictions in the durability of the republic itself.

Election betting must be understood within the social ecology of early American politics. The absence of scientific polling and centralized data collection meant that political knowledge circulated through conversation, newspapers, taverns, and partisan networks. Betting distilled this diffuse information into odds that reflected collective belief rather than official authority. Wagers aggregated rumor, local observation, and political intuition into a shared forecast, offering a rough but meaningful gauge of public sentiment. In this sense, election betting served as an informal epistemic system, translating political judgment into quantifiable stakes.

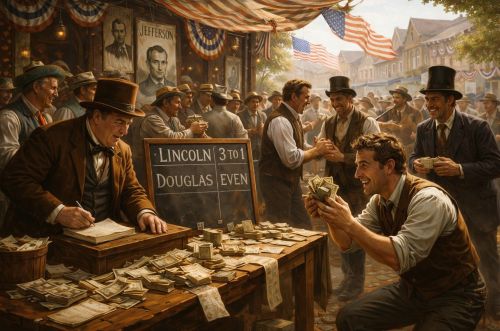

The practice also carried a pronounced ritual dimension. Many bets were structured less around financial gain than around public performance. Losers might be required to carry winners through town, submit to public shaving, or engage in other acts of symbolic humiliation. These rituals reinforced communal hierarchies and transformed electoral defeat into a visible, embodied acknowledgment of error. Such performances did not undermine democratic norms; they dramatized them. Loss was not hidden or abstracted but enacted, reinforcing the moral expectation that political judgment carried social accountability.

To dismiss election betting as mere gambling is to miss its deeper significance. Wagering on politics reflected a culture in which citizenship involved personal exposure to uncertainty and consequence. As the practice evolved and eventually disappeared, replaced by expert polling and regulated forms of gambling, Americans lost a participatory mode of prediction that once tied political belief directly to risk. Examining election betting therefore opens a window onto changing ideas about democracy, expertise, and the public’s role in interpreting political reality.

Political Culture in the Early Republic

In the decades following independence, American political culture developed in conditions of extraordinary informality. Elections were public events embedded in daily social life rather than insulated administrative procedures. Voting often occurred in open venues, surrounded by spectators, celebration, alcohol, and debate. Political allegiance was visible and performative, shaped by local reputation and personal trust rather than by abstract ideology alone. Within this environment, betting on elections emerged naturally as an extension of ordinary political expression, converting opinion into commitment through risk.

The early republic lacked centralized mechanisms for measuring public sentiment. There were no polls, no standardized surveys, and no professional class tasked with quantifying voter preference. Instead, political knowledge circulated through interpersonal networks: taverns, marketplaces, churches, and partisan newspapers. Election betting functioned as a way to synthesize these dispersed signals. Odds reflected accumulated judgment rather than statistical sampling, drawing upon local knowledge of turnout, factional strength, and candidate credibility. In this sense, wagers offered a collective estimate of political reality grounded in lived observation.

Taverns played a particularly important role in this culture. They served as hubs of political exchange where news was debated, alliances formed, and bets negotiated. Wagering was rarely a private act. It was conducted publicly, often loudly, and with witnesses. This visibility mattered. Bets were reputational statements, binding the bettor’s social standing to their political assessment. Winning enhanced credibility; losing imposed a social cost. Betting thus reinforced norms of accountability in political judgment, discouraging casual or insincere partisanship.

Partisan newspapers amplified and legitimized the practice. Editors regularly reported prominent wagers, large stakes, and shifting odds, treating them as meaningful indicators of momentum. In an era when editorial bias was explicit and expected, betting reports offered a seemingly objective signal derived from action rather than rhetoric. Readers could interpret odds as a proxy for confidence across communities, especially when regional bets contradicted or confirmed local expectations. Wagering markets, however informal, became part of the informational infrastructure of early American politics.

Election betting did not conflict with prevailing ideals of republican virtue. On the contrary, it aligned with a conception of citizenship that emphasized personal responsibility and moral courage. To wager was to stand publicly behind one’s judgment, accepting consequences rather than retreating into anonymity. While moral critics periodically objected to gambling, election betting was widely distinguished from games of chance. It was understood as a test of political insight rather than luck, reinforcing its legitimacy within the civic culture of the early republic.

Ritual, Honor, and the Performance of Loss

Election betting in early America was rarely resolved quietly. Loss was not merely acknowledged; it was enacted. Many wagers stipulated public performances rather than simple monetary payment, transforming political defeat into a social ritual. Acts such as pushing the winner through town in a wheelbarrow, carrying them on one’s back, or submitting to a public shaving were common forms of settlement. These rituals embedded elections within the physical life of communities, ensuring that outcomes were seen, remembered, and socially registered.

Such performances were rooted in older honor cultures that predated the republic. Early American society retained strong expectations that men stand visibly behind their judgments and accept the consequences of error. Public loss functioned as a corrective rather than a humiliation in the modern sense. It reaffirmed communal norms by demonstrating that political confidence carried obligations. The body became the medium through which political miscalculation was acknowledged, reinforcing the idea that citizenship required accountability as well as opinion.

These rituals also served to defuse political tension. Elections in the early republic were often bitter, personal, and emotionally charged. By channeling defeat into symbolic acts, communities converted conflict into performance rather than violence. Laughter, spectacle, and shared participation softened the sting of loss while preserving hierarchy and memory. The loser was marked, but not excluded. Having paid the price publicly, they were reintegrated into civic life with their credibility tested but intact.

The performance of loss reinforced the collective nature of political judgment. Election outcomes were not abstract tabulations but communal verdicts experienced through shared ritual. Betting settlements dramatized the fallibility of political prediction while affirming the legitimacy of the process itself. By accepting loss visibly, bettors acknowledged not only personal error but the authority of the electorate. In this way, ritualized defeat strengthened democratic norms by binding individual judgment to collective decision-making.

Elite Participation and High-Stakes Wagers

Election betting in early America was not confined to taverns or informal social circles. Political elites participated openly and, in many cases, spectacularly. Lawyers, financiers, newspaper editors, and officeholders wagered sums that far exceeded casual amusement, staking land, large quantities of cash, and long-term financial interests on electoral outcomes. These bets were often public knowledge, reported in newspapers and discussed widely, reinforcing the perception that wagering was a legitimate extension of political engagement rather than a disreputable vice.

The involvement of prominent figures lent election betting an aura of respectability and seriousness. When well-known politicians and professionals wagered on elections, they signaled confidence not only in their political judgment but in the stability of the electoral system itself. Bets of this scale presupposed that results would be honored and that institutions were strong enough to enforce outcomes. In this sense, elite wagering reflected trust in republican processes at moments when those processes were still relatively young and contested.

High-stakes bets also illustrate how closely politics and property were intertwined in the nineteenth century. Land wagers were particularly symbolic. To stake acreage on an election was to tie political outcomes directly to material foundations of status and power. Such bets dramatized the belief that elections shaped not merely officeholding but the broader distribution of wealth, influence, and opportunity. Losing carried real consequences, reinforcing the seriousness with which political outcomes were regarded.

Elite betting networks further contributed to the circulation of political information. Lawyers and financiers often possessed broader regional knowledge than ordinary voters, drawing on correspondence, commercial ties, and legal circuits. Their wagers were interpreted as informed signals rather than reckless gambles. Newspapers frequently cited these bets as indicators of momentum, treating elite confidence as a proxy for insider knowledge. In doing so, election betting blurred the line between popular participation and elite influence, binding both into a shared culture of political risk.

Betting Markets as Political Information Systems

Before the emergence of scientific polling, Americans relied on a patchwork of informal indicators to assess electoral prospects. Among the most influential of these were betting markets. Wagers transformed dispersed political impressions into visible, comparative signals. Odds reflected not only confidence in a candidate but the intensity and distribution of that confidence across communities. In the absence of systematic data, betting markets functioned as improvised instruments for aggregating political belief, offering a probabilistic sense of outcomes grounded in collective judgment.

Newspapers played a central role in translating these markets into public knowledge. Editors regularly published betting odds alongside partisan commentary, treating wagers as newsworthy facts rather than curiosities. Shifts in odds were interpreted as evidence of changing momentum, often linked to speeches, scandals, or regional developments. Readers learned to read these figures critically, weighing them against editorial bias and local experience. Betting odds thus entered the political conversation as one among several competing claims to insight, valued precisely because they represented action rather than rhetoric.

The informational value of election betting rested on the assumption that bettors were motivated by self-interest. Unlike partisan declarations, wagers imposed costs on error. This feature gave betting markets an aura of credibility. A person willing to risk money or property was presumed to possess confidence grounded in evidence rather than mere enthusiasm. While this assumption was not always justified, it shaped how contemporaries interpreted wagers. Betting markets were understood as imperfect but sincere attempts to forecast political reality.

At the same time, these markets were vulnerable to distortion. Wealthy bettors could attempt to sway perceptions by placing conspicuous wagers, and regional imbalances often skewed odds toward areas with greater capital concentration. Yet even these distortions were part of the informational ecology. Observers learned to interpret betting behavior contextually, discounting obvious bluffs or reading sudden surges as strategic signaling. In this way, election betting resembled early financial markets: volatile, uneven, and imperfect, but nonetheless capable of producing shared expectations in a world without formal measurement.

The Expansion and Professionalization of Election Betting

By the late nineteenth century, election betting had moved beyond taverns and informal side bets into well-organized markets with broad public visibility. Historical records show that betting on presidential elections in major cities like New York and other urban centers was not only common but clustered around recognizable institutions and brokers who facilitated regular wagering. These markets operated with many of the characteristics of financial exchanges: published odds, active trading, and professional intermediaries handling bets on behalf of clients. Such organization reflects how deeply embedded election wagering had become in American public life and anticipatory political culture.

The emergence of structured election betting markets coincided with broader economic and social changes in the post–Civil War United States. Industrialization, urbanization, and the rise of a national press expanded both the audience for political news and the capital available for speculative activity. Betting odds were disseminated widely in newspapers, becoming regular features that readers consulted much as they later would poll numbers. In effect, these markets aggregated dispersed political information into interpretable probabilities, mirroring emerging practices in commercial and financial markets.

Peak activity occurred in the early twentieth century, especially surrounding closely contested national elections. In the 1916 presidential contest between Woodrow Wilson and Charles Evans Hughes, millions of dollars changed hands in organized betting markets, with wagers flowing through brokers and informal exchanges in New York’s financial district. These markets drew large crowds and significant attention, much like modern prediction markets or sporting events, and they often generated their own data streams that newspapers printed alongside campaign coverage.

The professionalization of election betting also sparked institutional resistance. Established financial institutions such as the New York Stock Exchange grew concerned that visible wagering on political outcomes might tarnish their reputation, prompting formal efforts to distance official markets from speculative betting. Combined with the rise of parimutuel betting on horse racing and increasing anti-gambling legislation, these pressures helped erode the public presence of organized election wagering by the 1930s and 1940s. Thus, the very success and visibility of these professional markets eventually contributed to their decline, as shifts in legal norms and alternative forms of gambling supplanted them.

Moral Reform, Regulation, and the Decline of Wagering Politics

Election betting increasingly collided with shifting moral and political sensibilities as the nineteenth century came to a close. What had once been viewed as a participatory civic practice came under scrutiny from reformers who associated gambling with corruption, disorder, and social decay. Progressive Era movements reframed wagering not as a test of political judgment but as a threat to public morality and institutional integrity. This shift reflected broader anxieties about urbanization, immigration, and the concentration of economic power, all of which encouraged reformers to seek greater regulation of public life.

Anti-gambling campaigns gained momentum through a combination of moral rhetoric and legislative action. Reformers drew little distinction between betting on elections and other forms of wagering, arguing that all gambling fostered vice and undermined discipline. Laws restricting betting houses, exchanges, and public wagering increasingly targeted election markets alongside more familiar gambling venues. As legal pressure mounted, election betting was driven out of visible public spaces, severing its connection to communal ritual and informal political exchange.

At the same time, concerns about political corruption intensified. Reformers argued that large-scale election betting created incentives for manipulation, fraud, and undue influence. The spectacle of wealthy bettors placing conspicuous wagers was increasingly interpreted as evidence of elite domination rather than civic confidence. In an era marked by scandals involving patronage, machine politics, and financial speculation, election betting became symbolically linked to broader fears about the erosion of democratic accountability.

Institutional actors also played a role in marginalizing election wagering. Financial exchanges and respectable commercial organizations sought to distance themselves from political betting, fearing reputational damage and regulatory backlash. Efforts to professionalize finance and separate it from overt political speculation contributed to the gradual exclusion of election betting from legitimate economic spaces. What had once resembled a parallel information market increasingly appeared incompatible with emerging norms of professional neutrality.

The decline of election betting was therefore not the result of a single reform or prohibition but a convergence of cultural, legal, and institutional pressures. As wagering retreated from public view, it lost the social functions that had sustained it for generations. Stripped of ritual, visibility, and legitimacy, election betting no longer operated as a civic practice. Its disappearance marked a broader transformation in how Americans understood the proper boundaries between politics, morality, and public participation.

Polling, Expertise, and the End of Popular Prediction

The rise of scientific polling in the early twentieth century fundamentally altered how Americans understood political knowledge. Where election betting had relied on dispersed judgment and visible risk-taking, polling promised systematic measurement conducted by trained experts. Early polling organizations claimed to replace intuition and rumor with representative sampling and statistical rigor. This shift did more than improve accuracy; it redefined who was authorized to predict elections and how political uncertainty should be managed.

Polling reframed political prediction as a technical problem rather than a civic practice. Ordinary citizens no longer needed to test their judgment through wagers or public commitment. Instead, they were invited to consume predictions produced elsewhere, presented as neutral reflections of public opinion. This change narrowed the space for participatory forecasting. Prediction became something done to the public rather than by it, reinforcing a growing division between political experts and lay observers.

The authority of polling rested on its claim to objectivity. Numbers carried a persuasive power that betting odds, rooted in social practice, increasingly lacked. Poll results appeared detached from passion, interest, or performance, even though they were shaped by methodological choices and assumptions. As newspapers and radio embraced polling, odds derived from wagers came to seem archaic or unserious by comparison. The cultural legitimacy of betting as an information source steadily eroded.

This transition also aligned with broader transformations in political communication. Campaigns became more centralized and message-driven, while media coverage emphasized national trends over local variation. Polling fit neatly into this emerging landscape, offering snapshots of opinion that could be rapidly disseminated and updated. Election betting, by contrast, depended on local networks and sustained engagement. Its decline reflected not merely legal restriction but a mismatch with new rhythms of political life.

The end of popular prediction marked a subtle but significant shift in democratic experience. While polling increased accuracy and efficiency, it reduced opportunities for citizens to publicly stake their beliefs and confront uncertainty directly. Election betting had once bound political judgment to personal consequence, making prediction a form of participation. Polling replaced that relationship with mediated expertise, altering how Americans related to elections, risk, and the meaning of political knowledge.

World War II and the Final Eclipse of Election Betting

By the onset of World War II, election betting had already been pushed to the margins of American political life. Legal restrictions, moral reform campaigns, and the rise of polling had eroded its public legitimacy, but the wartime environment accelerated this decline decisively. The mobilization of the nation for total war reshaped civic priorities, emphasizing unity, discipline, and centralized authority. Practices associated with speculation and public wagering appeared increasingly incompatible with a political culture focused on national survival and collective purpose.

Wartime regulation further narrowed the space for election betting. Expanded federal oversight of finance, communications, and public assembly reduced opportunities for visible wagering markets to operate. At the same time, rationing, labor demands, and military service altered everyday routines, leaving less room for the sustained social engagement that election betting had once required. Politics itself became more constrained, with fewer overt displays of partisan conflict during periods of heightened national emergency.

Cultural attitudes toward gambling also shifted during the war years. Legalized and regulated forms of wagering, particularly horse racing, were increasingly framed as contained leisure activities rather than civic expressions. These venues offered predictable schedules, institutional oversight, and a clear separation from political life. Election betting, by contrast, lacked a sanctioned place within this emerging recreational economy. Without legal protection or cultural endorsement, it faded quietly rather than provoking overt suppression.

By the mid-twentieth century, election betting had effectively disappeared as a recognized political practice. Its eclipse was not sudden but cumulative, the result of overlapping transformations in law, culture, and political knowledge. World War II did not end election betting so much as close the final chapter on a practice already rendered obsolete. What remained was a political culture in which prediction was professionalized, participation was increasingly mediated, and the risks once publicly borne by citizens were absorbed by institutions.

Conclusion: What Was Lost When Americans Stopped Betting on Politics

The disappearance of election betting marked more than the end of a colorful political custom. It signaled a deeper transformation in how Americans related to uncertainty, judgment, and democratic participation. Betting once required citizens to convert belief into commitment, exposing political opinion to public risk and consequence. In doing so, it fostered a form of engagement that was active rather than consumptive, rooted in responsibility rather than abstraction. Its decline reflected a narrowing of the ways ordinary people could meaningfully participate in interpreting political outcomes.

Election betting also sustained a culture in which political knowledge was collectively produced rather than institutionally delivered. Odds emerged from conversation, observation, and local experience, imperfect but socially grounded. When prediction shifted to polling and expert analysis, accuracy improved, but authority moved upward and outward. Citizens became audiences to forecasts rather than contributors to them. The loss was not simply epistemic but civic: prediction ceased to be a shared exercise and became a professional service.

The ritual dimensions of election betting further underscore what vanished with its eclipse. Public performances of loss and acknowledgment reinforced norms of accountability that modern political culture struggles to replicate. Defeat was embodied, visible, and socially negotiated rather than abstracted into numbers and commentary. While such rituals could be exclusionary or coercive, they nevertheless bound individuals to the collective verdict of elections in ways that contemporary systems rarely achieve.

Remembering election betting is not an argument for its revival, nor a romantic endorsement of gambling as civic virtue. It is, instead, a reminder that democratic participation has historically taken forms that blurred the boundaries between politics, social life, and personal risk. As Americans ceded prediction to experts and institutions, they gained efficiency and precision but lost a participatory mode of political judgment that once made uncertainty a shared civic burden. The end of election betting thus reveals how democracy changes not only through laws and technologies but through the quiet disappearance of practices that once made political belief tangible.

Bibliography

- Benson, Lee. The Concept of Jacksonian Democracy: New York as a Test Case. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1961.

- Boyer, Paul. Urban Masses and Moral Order in America, 1820–1920. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978.

- Breen, T. H. Tobacco Culture: The Mentality of the Great Tidewater Planters on the Eve of Revolution. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1985.

- Bushman, Richard L. From Puritan to Yankee: Character and the Social Order in Connecticut, 1690–1765. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967.

- Converse, Jean M. Survey Research in the United States: Roots and Emergence, 1890–1960. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

- Ditz, Toby L. Property and Kinship: Inheritance in Early Connecticut, 1750–1820. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986.

- Formisano, Ronald P. The Transformation of Political Culture: Massachusetts Parties, 1790s–1840s. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983.

- Gustafson, Sandra M. “American Literature and the Public Sphere.” American Literary History 20:3 (2008): 465-478.

- Herbst, Susan. Numbered Voices: How Opinion Polling Has Shaped American Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993.

- Hillygus, D. Sunshine. “The Evolution of Election Polling in the United States.” Public Opinion Quarterly 75:5 (2011): 962-981.

- Hofstadter, Richard. The Idea of a Party System: The Rise of Legitimate Opposition in the United States, 1780–1840. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1960.

- Igo, Sarah E. The Averaged American: Surveys, Citizens, and the Making of a Mass Public. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Kasson, John F. Rudeness and Civility: Manners in Nineteenth-Century Urban America. New York: Hill and Wang, 1990.

- McGerr, Michael. The Decline of Popular Politics: The American North, 1865–1928. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Pasley, Jeffrey L. “The Tyranny of Printers”: Newspaper Politics in the Early American Republic. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2001.

- Rhode, Paul W., and Koleman S. Strumpf. “Historical Political Futures Markets: An International Perspective.” NBER Working Paper No. 14377, September 2008.

- —-. “Historical Presidential Betting Markets.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 18:2 (2004): 127-142.

- Schudson, Michael. The Good Citizen: A History of American Civic Life. New York: Free Press, 1998.

- Skowronek, Stephen. Building a New American State: The Expansion of National Administrative Capacities, 1877–1920. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- Smith, Daniel Blake. Inside the Great House: Planter Family Life in Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake Society. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1980.

- Strumpf, Koleman S. “The Long History of Political Betting Markets.” Working paper, 2012.

- Wiebe, Robert H. The Search for Order, 1877–1920. New York: Hill and Wang, 1967.

- Wood, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution. New York: Vintage Books, 1993.

Originally published by Brewminate, 01.15.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.