Gaza’s strategic location made it both a prize and a battleground.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Gaza under Early Muslim Rule (7th–10th Centuries)

The Muslim Conquest of Gaza

The early Muslim conquest of Gaza occurred during the wider Muslim expansion into the Levant in the first half of the 7th century, a campaign initiated under the Rashidun Caliphate following the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632 CE. Gaza, a city of considerable strategic and commercial importance located on the coastal route linking Egypt to the Levant, was then under Byzantine control. The Muslim forces, led by the seasoned general Amr ibn al-As, began their campaign in Palestine shortly after the successful invasion of the Arabian Peninsula and southern Syria. Gaza likely fell in 637 CE, around the same time as other major urban centers such as Jerusalem and Caesarea. While exact dates vary slightly among medieval Muslim sources, the conquest is generally placed after the decisive Battle of Yarmouk in 636 CE, which shattered Byzantine military resistance in Syria and paved the way for the Islamic occupation of Palestine, including Gaza.1

Unlike some other cities in the Levant, Gaza’s capture appears to have been relatively unopposed, possibly due to the already weakened state of Byzantine administration and military garrisons in the area. Byzantine forces had been strained by ongoing conflicts with the Sasanian Empire and internal instability within the empire itself. Moreover, the city’s population was religiously and ethnically diverse, including Christians, Jews, and Samaritan communities, many of whom may have viewed the Muslim conquerors as preferable to the often oppressive Byzantine authorities.2 Early Islamic sources suggest that the city surrendered under terms of a treaty (ʿahd), guaranteeing the safety of its inhabitants in exchange for tribute (jizya) and political submission. Such treaties were typical of the early conquests and aimed to incorporate conquered peoples into the Islamic polity while preserving social and economic continuity.3

Once under Muslim control, Gaza was integrated into the administrative system of the newly formed Islamic Caliphate. It became part of the jund (military district) of Filastin, with its capital eventually established at Ramla. The region retained much of its local administrative structure initially, as the Muslim rulers relied on existing Byzantine systems to maintain order and collect taxes. Gaza’s location ensured its continued economic importance as a node in the trade network linking Egypt with Syria and the Arabian Peninsula. Archaeological and textual evidence suggests that commerce remained robust, and Gaza’s markets likely prospered under the new regime. The early Muslim governors of Palestine emphasized infrastructure and security, encouraging agricultural production and urban stability, which would have contributed to Gaza’s sustained prosperity during the early Islamic period.4

In addition to its economic role, Gaza began to develop religious significance within the early Islamic world. It was the birthplace of Muhammad ibn Idris al-Shāfiʿī, the founder of the Shāfiʿī school of Sunni jurisprudence, who was born there in 767 CE. While this event occurred more than a century after the conquest, it reflects the city’s growing role as a center of learning and religious scholarship under Islamic rule. The construction of mosques and the gradual spread of Islamic culture and Arabic language contributed to the Islamization of the region. Yet, Islamization was a gradual process, and Christian and Jewish communities continued to exist in Gaza for centuries under the dhimma system, which allowed them to practice their religions under Muslim protection. This pragmatic approach to governance, characteristic of early Muslim rule, ensured relative religious harmony and administrative continuity in the newly conquered territories.5

The conquest of Gaza marked the beginning of a profound transformation not only of the city but also of the surrounding region. It ushered in a period of Islamic hegemony that would shape the political, cultural, and religious character of Palestine for centuries. As the Rashidun Caliphate gave way to the Umayyad and then the Abbasid Caliphate, Gaza continued to function as a strategically significant town on the southern frontier of Bilād al-Shām. Although it never attained the political centrality of cities like Damascus or Jerusalem, its role in the early Islamic conquests and its integration into the fabric of the caliphate’s provincial administration reflect its enduring importance. The relatively peaceful nature of its conquest and the policies that followed underscore the pragmatism and flexibility of early Islamic imperial expansion in the Levant.6

Administrative and Religious Changes

Following the Muslim conquest of Gaza in the 630s, the city underwent substantial administrative restructuring under the Rashidun Caliphate. It was incorporated into the province of Jund Filastin, one of the five military-administrative districts (ajnad) of Bilād al-Shām, the larger Levantine region of the Islamic empire. The Muslim conquerors, particularly during the early decades, employed a pragmatic approach to governance, maintaining many of the pre-existing Byzantine bureaucratic frameworks while placing them under the oversight of Arab Muslim officials. Taxation systems were adjusted rather than abolished; the jizya (poll tax) was introduced for non-Muslims, while the kharaj (land tax) replaced or adapted previous Byzantine land levies. These fiscal policies ensured the economic stability of the region and facilitated the smooth integration of Gaza into the early Islamic polity.7

One of the most notable administrative shifts was the gradual Arabization of Gaza’s civil and political infrastructure. Though Greek remained in use during the transitional phase, particularly among Christian communities and in some fiscal registers, Arabic was promoted as the language of government. By the early Umayyad period (661–750), Arabic had largely supplanted Greek as the administrative language in Gaza and across the wider province of Palestine. This transformation was part of the broader Arabization and Islamization policies initiated by the Umayyad caliph ʿAbd al-Malik (r. 685–705), who mandated Arabic as the official language of administration throughout the empire. These changes did not eradicate local customs or Christian bureaucrats overnight, but they marked the beginning of a slow yet definitive shift in Gaza’s cultural and political orientation.8

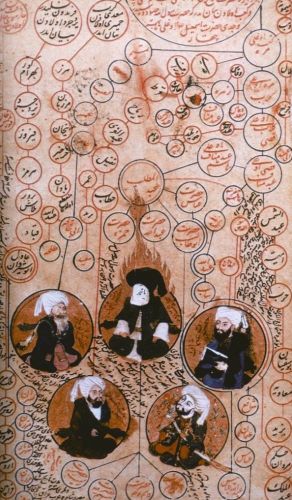

Religiously, the conquest introduced profound changes while also accommodating continuity. Islam was established as the dominant faith and ideological framework of the state, and the construction of mosques in Gaza followed accordingly. The earliest mosques were often built on or near previous sites of religious significance, symbolizing both continuity and transformation. However, the early Muslim rulers generally did not enforce conversion by coercion. Instead, Christians and Jews—classified as dhimmīs under Islamic law—were allowed to maintain their religious practices and communal structures in exchange for paying the jizya. This system created a layered religious society in Gaza, with Islam increasingly influential in public and political life, while Christianity and Judaism remained visible in the private and communal spheres.9

The Umayyad and Abbasid periods saw a deepening of Islamic religious life in Gaza. Institutions such as madrasas, kuttāb (Qurʾanic schools), and mosques contributed to the religious education and Islamic identity of the region. The city gained prestige in the Islamic world as the birthplace of Imam al-Shāfiʿī (767–820 CE), a key figure in Islamic jurisprudence and founder of one of the four major Sunni legal schools. Although he spent much of his life elsewhere, al-Shāfiʿī’s connection to Gaza elevated the city’s religious reputation. Muslim scholars and pilgrims frequented the area, and Gaza became part of the Islamic intellectual network that spanned the caliphate. While Christian and Jewish communities continued to exist—often centered around their own schools, synagogues, and churches—the demographic and cultural tide increasingly favored Islam.10

Despite the growing dominance of Islam, the Islamic rulers generally adhered to a policy of religious tolerance within the parameters of Islamic law. Gaza’s Christians maintained ecclesiastical hierarchies and places of worship, and Jews preserved synagogues and educational institutions. Some church properties were confiscated or converted—either during initial conquests or later under particular rulers—but many were left untouched. This approach to governance fostered a relatively stable coexistence that contrasted with periods of more aggressive religious intolerance in Byzantine or later Crusader rule. Thus, Gaza under early Muslim rule reflected the empire’s broader model: an Islamic state with a strong administrative core, fostering cultural assimilation over generations while tolerating a spectrum of religious traditions.11

Gaza in Islamic Historiography and Scholarship

Gaza’s role in Islamic historiography reflects its enduring symbolic, religious, and strategic significance in the early Islamic world and beyond. Although not a central capital like Damascus or Baghdad, Gaza appears in several early Arabic historical and geographical works, where it is often mentioned in the context of the Islamic conquests, trade routes, and biographies of notable scholars. Authors such as al-Balādhurī (d. 892) and al-Yaʿqūbī (d. 897) include Gaza in their narratives of the Muslim conquest of Palestine, emphasizing its peaceful submission and economic importance. Al-Balādhurī’s Futūḥ al-Buldān records the terms of surrender offered to the city’s Christian population, preserving the memory of Gaza as one of the Levantine cities integrated into Islam through diplomacy as much as force.12 These early narratives contributed to a framework in which Gaza was remembered not only as a conquered site but as a model of pragmatic Islamic governance.

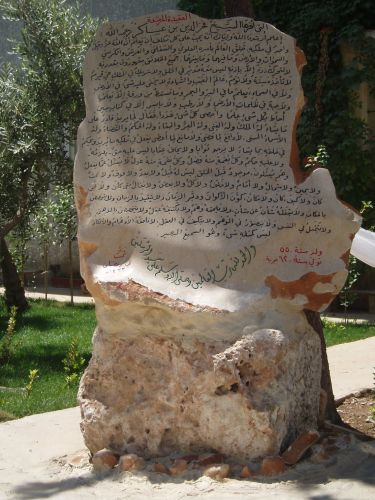

The city gains further attention in Islamic biographical literature due to its association with Imām al-Shāfiʿī, founder of the Shāfiʿī madhhab. Born in Gaza in 767 CE, his birthplace became a point of pride for later historians and religious scholars. Authors like al-Dhahabī (d. 1348) and Ibn Kathīr (d. 1373) highlight al-Shāfiʿī’s Gaza origins as they trace his intellectual development in their compendia of Islamic scholarship. In texts such as al-Dhahabī’s Siyar Aʿlām al-Nubalā’, Gaza is presented as a spiritually significant locale by virtue of its connection to the great jurist. Although al-Shāfiʿī left Gaza at a young age, the city’s association with his early life endowed it with an enduring scholarly aura, especially within Sunni legal and intellectual traditions.13 Thus, historiography transformed a relatively peripheral city into a symbolic birthplace of legal knowledge and piety.

Islamic geographers and travel writers also contributed to the historiographical construction of Gaza. Scholars like al-Muqaddasī (d. late 10th century), who was himself a native of Jerusalem, included Gaza in his work Aḥsan al-Taqāsīm fī Maʿrifat al-Aqālīm, offering both descriptive and evaluative accounts of the city. He praised Gaza’s markets, agricultural produce, and strategic coastal position, noting its role in trade between Egypt and the Levant. These travelogues reflect a broader interest in documenting the practical and cultural geography of the Islamic world, and they often elevate Gaza’s importance by embedding it in larger narratives of Islamic prosperity and administrative cohesion. Al-Muqaddasī’s inclusion of Gaza alongside major cities like Jerusalem and Ramla underscores its regional value and the degree to which Islamic scholars sought to define the Islamic world through the careful documentation of its urban centers.14

Later Islamic historians writing under the Ayyubid and Mamluk dynasties revisited Gaza in the context of the Crusades and their aftermath. Authors like Ibn al-Athīr (d. 1233) and al-Maqrīzī (d. 1442) recount military movements and political changes in and around Gaza as part of the larger jihad against the Crusaders. In these narratives, Gaza often appears as a frontier zone or buffer town, caught between Muslim and Frankish control. Such references reinforce the image of Gaza as a site of both continuity and conflict—a city whose value lay in its ability to serve as a military base, a refugee corridor, and a place of symbolic resistance. Moreover, these authors often contextualized Gaza within broader Islamic concerns about unity, governance, and the defense of sacred lands, thus situating it within a moral geography as much as a physical one.15

Modern Islamic historiography continues to revisit Gaza as a microcosm of Islamic history and identity. Contemporary Muslim scholars, particularly from Palestine and the broader Arab world, often invoke Gaza as a symbol of resilience and religious heritage. The memory of al-Shāfiʿī, the record of early Islamic tolerance, and the legacy of resistance during the Crusades are reinterpreted to assert Islamic historical claims and cultural continuity in the region. Gaza thus functions not only as a geographical entity but as a palimpsest of Islamic historical memory, invoked to articulate narratives of justice, perseverance, and sacred geography. These themes echo across medieval and modern texts alike, suggesting that Gaza’s place in Islamic historiography has always been shaped as much by ideology as by empirical reality.16

Gaza during the Crusades (1096–1291)

The First Crusade and its Aftermath

The First Crusade (1096–1099) brought profound political and religious upheaval to the Levant, and although Gaza was not an initial focal point of Crusader military campaigns, its strategic location made it an inevitable point of interest. After the Crusaders captured Jerusalem in July 1099, they turned their attention to consolidating control over the surrounding areas. Gaza, situated on the coastal road between Egypt and the Levant, became an essential node in the broader effort to fortify Crusader hegemony in the southern frontier of the newly established Kingdom of Jerusalem. The city’s proximity to Egypt, still under the rule of the Fatimid Caliphate, made it a target of strategic importance for both sides. Although the initial Crusader conquest of Gaza did not occur immediately after Jerusalem’s fall, it was eventually occupied in the early 12th century and integrated into the Crusader administrative framework as a fortified town and garrison post.17

The Crusaders made Gaza a military outpost designed to resist incursions from the south and serve as a launch point for operations toward Egypt. The town was fortified with new defenses and garrisoned with knights and infantry, many of whom belonged to the military orders, particularly the Templars. These efforts were part of a broader Latin strategy to build a network of fortified positions to protect the Kingdom of Jerusalem’s borders. However, Gaza’s largely Muslim and Christian population was viewed with suspicion by Crusader leaders, and although some Eastern Christians were tolerated, the Latin authorities often enforced conversions, imposed new taxes, or displaced non-Latin clerical leadership. Religious structures such as mosques were converted into churches, and Latin ecclesiastical institutions were established, though local resistance persisted, particularly from Muslim residents and Orthodox Christians who viewed the Latin occupiers as foreign interlopers.18

Despite Crusader fortification efforts, Gaza was repeatedly contested in the decades following the First Crusade. The city’s position made it a target of frequent Fatimid raids and, later, Saladin’s campaigns. Its location along key trade and military routes meant that no occupying force could hold it without considerable resources and coordination. In 1170, Saladin’s forces launched a major attack on Gaza, and by 1187—after the decisive Battle of Hattin—he had successfully taken control of much of the region, including Gaza. Saladin’s conquest was part of a wider Islamic resurgence in response to nearly a century of Crusader occupation. Under his rule, Gaza was reintegrated into the Ayyubid administrative system, and Islamic institutions were reestablished. Mosques were rebuilt or reconverted, and scholars, judges, and administrators restored the Islamic religious and legal order, undoing many of the Latin innovations of the previous century.19

In the aftermath of the Crusader expulsion, Gaza became a site of symbolic importance in Muslim memory and historiography. Chroniclers such as Ibn al-Athīr and later Mamluk historians emphasized the city’s liberation as part of a broader Islamic victory narrative. Gaza was portrayed as a border town that had endured foreign occupation but ultimately returned to the fold of Islamic governance, reflecting divine justice and Muslim perseverance. While not as symbolically charged as Jerusalem, Gaza nevertheless emerged as a key example of the larger jihad effort against the Franks. The city’s shifting control became a case study in the cyclical nature of war and resistance, and its recovery served to validate the spiritual and political legitimacy of leaders like Saladin, whose legacy would shape Islamic political thought for centuries.20

After the First Crusade and the reassertion of Muslim control, Gaza’s urban and religious landscape underwent yet another transformation. The Ayyubids and, later, the Mamluks sought to rebuild the city not only physically but also spiritually. Religious endowments (waqf) were established to fund mosques, schools, and charitable institutions. Sufi orders also gained a presence in Gaza, adding a layer of devotional life that had not been emphasized under either the Crusaders or earlier Islamic rulers. The reconstruction of Islamic Gaza was part of a wider ideological effort to erase Latin influence and re-inscribe the city within the moral and religious geography of the Islamic world. Though the scars of Crusader occupation remained, Gaza emerged from the First Crusade and its aftermath as a renewed stronghold of Islamic learning and resilience—a status it would continue to build upon in subsequent centuries.21

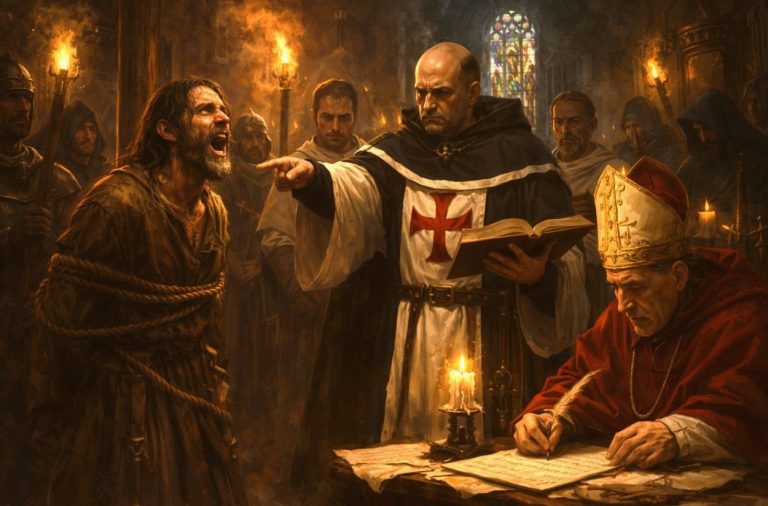

Fortification and Latin Christianization

During the Crusader occupation of Palestine, the city of Gaza held immense strategic value due to its location along the vital coastal route between Egypt and the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Following the consolidation of Crusader control over Jerusalem in 1099 and the gradual expansion of Latin influence southward, Gaza became a target for military fortification. The Crusaders sought to secure the southern frontier of their kingdom against both Fatimid incursions from Egypt and Bedouin raids. By the mid-12th century, under the reign of King Baldwin III, Gaza was transformed into a heavily fortified garrison town. The construction of robust walls, towers, and a keep—likely built upon earlier Roman-Byzantine foundations—signaled the city’s new military role. These fortifications were not merely defensive structures but expressions of the Latin rulers’ intent to remake the city in their own image, physically and ideologically.22

Central to this ideological transformation was the Christianization of Gaza under Latin auspices. The Crusaders converted existing mosques and churches into Latin places of worship, often rededicating them to saints significant to Western Christianity. For example, churches were dedicated to Saint Porphyrius and the Virgin Mary, aligning Gaza with the Latin Church’s devotional framework. This effort to Latinize religious life was accompanied by the appointment of Latin clergy, who replaced or marginalized Eastern Christian and Muslim religious figures. The transformation extended to the imposition of Latin liturgy and the integration of Gaza into the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem. The presence of monastic orders such as the Templars, who were granted properties and tasked with defending the region, further institutionalized Latin Christian presence. The combination of military and religious colonization was designed to fuse Latin identity with the physical and spiritual life of the city.23

Gaza’s fortifications and Latin Christian infrastructure served both symbolic and practical purposes. On one hand, the fortresses and churches represented the triumph of Christendom over Islam, a tangible realization of the Crusaders’ religious mission. On the other, they functioned as logistical and military hubs supporting Latin campaigns into Egypt and defending against Ayyubid counterattacks. Gaza was also the southernmost Latin stronghold in Palestine for much of the 12th century, which made it a critical base for Crusader operations. In the 1140s and 1150s, Baldwin III oversaw further enhancements to the city’s fortifications and religious institutions. Latin chroniclers such as William of Tyre regarded the city’s transformation as part of a divine mandate to reclaim and Christianize the Holy Land, though they often omitted or minimized the continued presence of non-Latin populations.24

Nevertheless, the Latin Christianization of Gaza was never absolute. Despite efforts to Latinize the city, Muslim and Eastern Christian communities persisted, albeit under increasingly restricted conditions. Indigenous Christians were often required to conform to Latin liturgical practices or face exclusion from civic and religious life. Muslim residents, when not expelled, lived under heavy taxation and social marginalization. Moreover, the Latin control of Gaza remained tenuous due to its exposed position. Saladin’s campaigns in the 1170s and 1180s posed a constant threat, culminating in the city’s recapture after the Battle of Hattin in 1187. Upon its reoccupation, Saladin reportedly demolished much of the Latin fortifications and reestablished Islamic governance and institutions, reversing nearly a century of Latin Christian influence. This reversal reflected the fragility of the Crusader presence in the region, especially in contested border zones like Gaza.25

The Crusader period in Gaza left behind a layered legacy that intertwined militarization with religious transformation. While Latin fortifications and churches were symbols of Christian imperial ambition, their limited endurance revealed the difficulties of maintaining cultural and religious hegemony in a predominantly non-Latin region. Modern archaeological surveys in Gaza have uncovered remains of Crusader-era structures, including fort walls and ecclesiastical buildings, offering tangible evidence of Latin occupation. These remnants, alongside contemporary accounts, paint a picture of a city forcibly integrated into the Crusader polity yet resistant to total transformation. Gaza’s experience during the Crusades underscores the complex interplay between power, faith, and resistance in the medieval Levant, where religious identity and military architecture were inextricably linked.26

Saladin and the Ayyubid Recapture

The recapture of Gaza by Saladin in the late 12th century was a key milestone in the Islamic response to Crusader expansion in the Levant. Following the catastrophic defeat of the Crusader armies at the Battle of Ḥaṭṭīn in July 1187, Saladin swiftly moved to reclaim key territories that had been under Frankish control for nearly a century. Gaza, a strategically situated city on the coastal route between Egypt and Palestine, had been fortified and Latinized under Crusader rule, but it remained a vulnerable frontier town. Its capture was part of Saladin’s broader campaign to eliminate Crusader strongholds and reestablish Muslim control over the Levantine corridor. By the end of 1187, Gaza fell to Ayyubid forces with relatively little resistance, largely due to the demoralization and retreat of Crusader troops after their loss at Ḥaṭṭīn and the fall of Jerusalem.27

Saladin’s military reconquest of Gaza was accompanied by an ideological and religious campaign to restore Islamic institutions and practices. The Latin fortifications were partially dismantled, and mosques that had been converted into churches were reconsecrated for Muslim worship. The reinstallation of Islamic law and governance signaled a decisive break with the Crusader era. Saladin’s approach to urban governance emphasized continuity with earlier Islamic rule, drawing on Fatimid and Abbasid models of administration. He appointed loyal governors and judges who could implement Ayyubid legal and religious policies, thereby ensuring the reintegration of Gaza into the wider Islamic polity. These efforts were not merely bureaucratic—they were meant to reassert the moral and spiritual identity of the city as part of the dār al-Islām.28

Saladin’s restoration of Gaza had symbolic resonance across the Muslim world. Chroniclers such as Ibn al-Athīr and Imad al-Din al-Isfahani portrayed the city’s liberation as a microcosm of the larger triumph of Islam over foreign aggression. These writers emphasized the piety and justice of Saladin, framing his conquest not only as a military victory but as a fulfillment of divine will. Gaza was no longer a frontier town but a sanctified city recovered from the hands of unbelievers. Islamic historiography of the period often glossed over the complexities of local collaboration or the persistence of Christian communities, preferring instead to highlight the city’s complete “purification” under Saladin’s rule. This rhetorical strategy served both as a morale booster and a legitimizing narrative for the Ayyubid dynasty.29

Economically and culturally, Gaza began to flourish once again under Ayyubid patronage. Saladin and his successors reestablished waqf (charitable endowments) to fund the restoration of religious and educational institutions. Madrasas and Sufi lodges began to emerge, signaling a revival of Islamic learning and spiritual life in the city. Gaza’s role as a node in regional trade routes also rebounded, benefiting from renewed ties with Egypt and inland Syria. Though still recovering from the disruption of war and Crusader occupation, the city’s revival was marked by a concerted effort to reforge its Islamic character in both form and substance. Unlike the Latin rulers who had imposed an external religious framework, the Ayyubids sought to cultivate indigenous forms of worship and governance that resonated with Gaza’s historical identity.30

The recapture of Gaza ultimately laid the foundation for its later role under Mamluk and Ottoman rule. Saladin’s campaign was more than a military maneuver—it was a deliberate act of restoration that connected Gaza to the larger Islamic world in both ideology and infrastructure. Although later Crusader incursions would again threaten parts of Palestine, Gaza remained under Muslim control for the rest of the medieval period. The city’s experience during this transitional phase illustrates the broader patterns of resilience, adaptation, and memory in Islamic civilization. Saladin’s reconquest of Gaza, therefore, was not only a pivotal moment in the history of the Crusades but also a defining episode in the construction of a post-Crusader Islamic identity in the Levant.31

The Later Crusades and Mamluk Control

Following Saladin’s reconquest of Gaza in 1187, the city was securely integrated into the Ayyubid Sultanate. However, the onset of the later Crusades in the 13th century once again threatened the political stability of the southern Levant. The Fifth and Seventh Crusades, which were launched with an emphasis on invading Egypt, indirectly impacted Gaza due to its location along the coastal route between the Nile Delta and the Holy Land. Though Gaza did not witness major battles during these later campaigns, its proximity to the Crusader frontier made it a critical defensive outpost. The Ayyubid rulers, and later their Mamluk successors, recognized the city’s strategic importance and fortified it accordingly to prevent further Crusader encroachments from the coastal enclaves still held by European forces into the mid-13th century.32

With the decline of Ayyubid power and the rise of the Mamluk Sultanate in the 1250s, Gaza entered a new phase of administrative and military importance. The Mamluks, a military caste of former slaves who established one of the most powerful Islamic states of the medieval period, adopted a proactive policy of frontier defense and internal consolidation. Gaza was incorporated into the province (niyāba) of Damascus but maintained a special status due to its geographical significance. Sultan Baybars (r. 1260–1277), in particular, invested in rebuilding the city’s defenses and religious institutions, seeing Gaza as both a bulwark against Crusader remnants and a key node in the internal communications of the sultanate. His campaigns into Palestine aimed not only to suppress Crusader strongholds but also to reassert Islamic orthodoxy and administrative efficiency in newly re-secured areas like Gaza.33

The Mamluks initiated a vigorous campaign of Islamization and urban development in Gaza, continuing and expanding on the foundations laid by the Ayyubids. The construction of mosques, madrasas (Islamic schools), khānqāhs (Sufi lodges), and caravansaries facilitated the city’s integration into the religious and economic networks of the Mamluk empire. Baybars personally ordered the restoration of the Great Mosque of Gaza, originally converted into a church during Crusader rule, and supported the establishment of religious endowments (awqāf) that funded education and social services. The Mamluks viewed Gaza as a model frontier town, emblematic of the Islamic resurgence in formerly contested territories. Over time, the city became a center of Sufi activity, and several prominent scholars, including al-Suyūṭī, later wrote about its religious significance.34

Militarily, Gaza remained a garrison town, regularly staffed by Mamluk cavalry (faris) and supplied through a well-maintained road system linking Cairo, Damascus, and Jerusalem. The Mamluk administrative apparatus ensured that taxes were collected efficiently and that law and order were maintained, often through the appointment of military governors (nā’ib). Gaza’s relative distance from the Mediterranean coast and its fortified inland position made it a less vulnerable target for Crusader raids, especially after the fall of Acre in 1291, which marked the end of Latin Christian political presence in the Levant. Thereafter, Gaza served as a rear base for campaigns against Bedouin uprisings and Mongol incursions in the region. Its transformation from a militarized frontier zone into a stable provincial town reflected broader Mamluk success in neutralizing the Crusader threat and restoring Islamic hegemony in the eastern Mediterranean.35

By the 14th century, Gaza had assumed a more settled role in the Mamluk provincial hierarchy, contributing to the scholarly, commercial, and religious life of the sultanate. Though no longer on the frontlines of warfare, the city remained symbolically important as a site of earlier Crusader-Islamic contestation. It retained a distinctly Islamic character, with institutions that trained religious scholars and hosted mystics from across the Muslim world. The memory of Crusader occupation persisted in local narratives and architectural remnants, but it was firmly eclipsed by the Mamluk achievement of restoring Gaza to the dār al-Islām. By the time the Ottomans absorbed the region in the early 16th century, Gaza had already been firmly re-established as a vital, well-integrated provincial city of the Islamic world, its Mamluk legacy enduring in its mosques, schools, and urban layout.36

Conclusion

Gaza’s history during the early Muslim rule and the Crusades reflects the broader dynamics of conflict, cultural exchange, and political transformation that defined the medieval Near East. From a thriving center under the Rashidun, Umayyad, and Abbasid caliphates to a contested frontier between Crusader and Muslim forces, Gaza’s strategic location made it both a prize and a battleground. Despite cycles of conquest and destruction, Gaza endured as a vital link in the networks of empire, religion, and commerce. The city’s resilience and adaptability during these centuries foreshadowed its continued significance in the centuries to follow.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Fred M. Donner, The Early Islamic Conquests (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981), 155–57.

- Walter E. Kaegi, Byzantine Palestine and Arabia in the Early Muslim Conquests (Brookfield: Ashgate, 1992), 93–95.

- Hugh Kennedy, The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In (London: Da Capo Press, 2007), 106–108.

- Moshe Gil, A History of Palestine, 634–1099, trans. Ethel Broido (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 77–82.

- Chase F. Robinson, Empire and Elites after the Muslim Conquest: The Transformation of Northern Mesopotamia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 134–136.

- Patricia Crone, Slaves on Horses: The Evolution of the Islamic Polity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), 41–44.

- Gil, A History of Palestine, 77-78.

- Donner, The Early Islamic Conquests, 269-272.

- Hugh Kennedy, The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the Sixth to the Eleventh Century, 2nd ed. (Harlow: Pearson, 2004), 118–120.

- Robinson, Empire and Elites after the Muslim Conquest, 135.

- Robert G. Hoyland, Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam (Princeton: Darwin Press, 1997), 393–395.

- Aḥmad ibn Yaḥyā al-Balādhurī, Futūḥ al-Buldān, trans. Philip Hitti (New York: Columbia University Press, 1916), 220–221.

- Shams al-Dīn al-Dhahabī, Siyar Aʿlām al-Nubalā’, ed. Shuʿayb al-Arnaʾūṭ (Beirut: Mu’assasat al-Risāla, 1982), 10:73–75.

- al-Muqaddasī, The Best Divisions for Knowledge of the Regions, trans. Basil Collins (Reading: Garnet Publishing, 2001), 147–149.

- Ibn al-Athīr, al-Kāmil fī al-Tārīkh, ed. C.J. Tornberg (Leiden: Brill, 1851–76), 11:328–330; al-Maqrīzī, al-Khiṭaṭ, ed. Ayman Fu’ad Sayyid (Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 2002), 3:102–104.

- Rashid Khalidi, Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997), 79–82.

- Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades, Vol. 1: The First Crusade and the Foundation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1951), 285–287.

- Christopher Tyerman, God’s War: A New History of the Crusades (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006), 377–379.

- Carole Hillenbrand, The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1999), 342–344.

- Ibn al-Athīr, al-Kāmil fī al-Tārīkh, 12:145-157.

- Amalia Levanoni, “The Islamization of Gaza during the Ayyubid and Mamluk Periods,” in The Mamluk Empire and Its Periphery, ed. Reuven Amitai and Stephan Conermann (Münster: LIT Verlag, 2009), 119–122.

- Denys Pringle, The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: A Corpus, Volume II (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 90–92.

- Benjamin Z. Kedar, Crusade and Mission: European Approaches toward the Muslims (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), 56–58.

- William of Tyre, A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea, trans. Emily Atwater Babcock and A.C. Krey (New York: Columbia University Press, 1943), 2:318–320.

- Hillenbrand, The Crusades, 347-349.

- Adrian J. Boas, Jerusalem in the Time of the Crusades: Society, Landscape and Art in the Holy City under Frankish Rule (London: Routledge, 2001), 153–155.

- Hillenbrand, The Crusades 351-353.

- Malcolm Cameron Lyons and D.E.P. Jackson, Saladin: The Politics of the Holy War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 245–248.

- Ibn al-Athīr, al-Kāmil fī al-TārīkhI, 12:178-181.

- Levanoni, “The Islamization of Gaza during the Ayyubid and Mamluk Periods,”, 122-124.

- Paul M. Cobb, The Race for Paradise: An Islamic History of the Crusades (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 217–219.

- Hillenbrand, The Crusades, 384-386.

- Linda Northrup, From Slave to Sultan: The Career of Al-Mansur Qalawun and the Consolidation of Mamluk Rule in Egypt and Syria (678–689 A.H./1279–1290 C.E.) (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1998), 87–89.

- Levanoni, “The Islamization of Gaza during the Ayyubid and Mamluk Periods,”, 122-126.

- Reuven Amitai, Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War, 1260–1281 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 133–135.

- Michael Chamberlain, Knowledge and Social Practice in Medieval Damascus, 1190–1350 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 67–70.

Bibliography

- al-Balādhurī, Aḥmad ibn Yaḥyā. Futūḥ al-Buldān. Translated by Philip Hitti. New York: Columbia University Press, 1916.

- al-Dhahabī, Shams al-Dīn. Siyar Aʿlām al-Nubalā’. Edited by Shuʿayb al-Arnaʾūṭ. Beirut: Muʾassasat al-Risāla, 1982.

- al-Maqrīzī, Taqī al-Dīn Aḥmad. al-Khiṭaṭ. Edited by Ayman Fuʿād Sayyid. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 2002.

- al-Muqaddasī. The Best Divisions for Knowledge of the Regions. Translated by Basil Collins. Reading: Garnet Publishing, 2001.

- Amitai, Reuven. Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War, 1260–1281. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Boas, Adrian J. Jerusalem in the Time of the Crusades: Society, Landscape and Art in the Holy City under Frankish Rule. London: Routledge, 2001.

- Chamberlain, Michael. Knowledge and Social Practice in Medieval Damascus, 1190–1350. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Cobb, Paul M. The Race for Paradise: An Islamic History of the Crusades. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Crone, Patricia. Slaves on Horses: The Evolution of the Islamic Polity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980.

- Donner, Fred M. The Early Islamic Conquests. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981.

- Gil, Moshe. A History of Palestine, 634–1099. Translated by Ethel Broido. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Hillenbrand, Carole. The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1999.

- Hoyland, Robert G. Seeing Islam as Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam. Princeton: Darwin Press, 1997.

- Ibn al-Athīr. al-Kāmil fī al-Tārīkh. Edited by C.J. Tornberg. Leiden: Brill, 1851–76.

- Kaegi, Walter E. Byzantine Palestine and Arabia in the Early Muslim Conquests. Brookfield: Ashgate, 1992.

- Kedar, Benjamin Z. Crusade and Mission: European Approaches toward the Muslims. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984.

- Kennedy, Hugh. The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In. London: Da Capo Press, 2007.

- Kennedy, Hugh. The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the Sixth to the Eleventh Century. 2nd ed. Harlow: Pearson, 2004.

- Khalidi, Rashid. Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.

- Levanoni, Amalia. “The Islamization of Gaza during the Ayyubid and Mamluk Periods.” In The Mamluk Empire and Its Periphery, edited by Reuven Amitai and Stephan Conermann, 115–132. Münster: LIT Verlag, 2009.

- Lyons, Malcolm Cameron, and D.E.P. Jackson. Saladin: The Politics of the Holy War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- Northrup, Linda. From Slave to Sultan: The Career of Al-Mansur Qalawun and the Consolidation of Mamluk Rule in Egypt and Syria (678–689 A.H./1279–1290 C.E.). Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1998.

- Pringle, Denys. The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: A Corpus, Volume II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Robinson, Chase F. Empire and Elites after the Muslim Conquest: The Transformation of Northern Mesopotamia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Runciman, Steven. A History of the Crusades, Vol. 1: The First Crusade and the Foundation of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1951.

- Tyerman, Christopher. God’s War: A New History of the Crusades. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006.

- William of Tyre. A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea. Translated by Emily Atwater Babcock and A.C. Krey. New York: Columbia University Press, 1943.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.03.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.