From the clockwork charm of 19th-century automata to the cold circuitry of 20th-century surveillance, machines have not only extended human reach but have obscured it, redirected it, and, at times, betrayed it.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Allure of the Machine and the Craft of Illusion

In the modern imagination, technology has often served as a symbol of clarity, precision, and advancement. Yet alongside its transformative potential lies a more ambivalent history: one in which machines did not merely extend human capacity, but also masked, manipulated, and misled. In both the 19th and 20th centuries, emerging technologies did not simply reflect modernity, they also enabled new modes of deception. From pseudo-automata and spiritualist contraptions to propaganda radios and scientific charlatanry, technological fraud flourished in step with innovation. These were not outliers in the march of progress but reflections of its shadow, revealing the vulnerability of modern societies to the persuasive authority of the machine.

Spectacles of Trickery in the Industrial Century

Mechanical Marvels and Manufactured Minds

The 19th century, often hailed as the crucible of industrial modernity, also nurtured a particularly theatrical form of deceit. Few artifacts better symbolize this convergence of ingenuity and illusion than the revived spectacle of the “Mechanical Turk.” Originally devised in the 18th century by Wolfgang von Kempelen, the automaton reemerged in the 19th-century cultural circuit, retooled for audiences eager to witness the dawn of machine intelligence. This faux chess-playing automaton, seemingly able to defeat human opponents, concealed a human operator within its cabinetry.1

What is striking is not merely the spectacle’s capacity to deceive but the eagerness of the public to believe. The Turk reflected more than clever engineering; it embodied a desire to see intelligence mechanized. This illusion, repeated in various guises, exploited the public’s shallow understanding of machinery and the almost mystical reverence accorded to its precision. The deception functioned not in spite of the machine, but because of it.

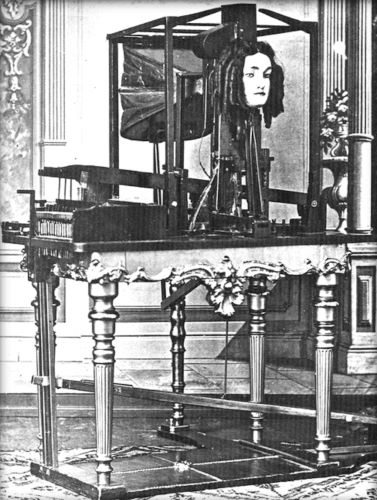

The Euphonia and the Voice of Mechanical Fraud

Another remarkable instance of mechanized deception emerged in the form of Joseph Faber’s Euphonia, a 19th-century machine designed to imitate human speech. Unveiled to audiences in the mid-1800s, the Euphonia featured an eerie female mask connected to bellows, levers, and reeds, all carefully constructed to produce the phonetic elements of language. The inventor claimed it could speak in multiple languages with uncanny clarity. In truth, the device required constant human manipulation, and its vocalizations were stiff and limited at best.2

Nonetheless, the machine captivated onlookers, many of whom interpreted its performance as a precursor to artificial speech. Some even speculated that future machines might replace human orators altogether. The Euphonia represents not merely a technological curiosity, but a case study in how the theatrical promise of machinery could be inflated beyond its actual capabilities. Its deception was not in what it said, but in the belief it inspired: that technology could soon speak with a soul.

Phrenological Devices and the Veneer of Scientific Precision

Equally emblematic of the era’s pseudo-scientific allure were phrenological machines—devices that claimed to diagnose mental traits by measuring the bumps and contours of the skull. Often made of polished brass and festooned with dials and calibrated arms, these instruments mimicked the aesthetic of scientific authority. While the theory of phrenology itself has long been discredited, in its heyday, such machines were wielded to lend credibility to charlatans who promised character analyses, career guidance, and even marital compatibility readings.3

The technology here served less to explore the human mind than to legitimize assumptions about race, intelligence, and morality. As such, these machines reveal not simply a failure of science, but a manipulation of its visual and rhetorical authority. They functioned as instruments of belief, not inquiry, and their fraudulence was often indistinguishable from their spectacle.

Broadcasting Belief: Propaganda, Control, and Technological Theater

Radio as Ideological Instrument in Nazi Germany

In the 20th century, deception was scaled up, mechanized, and nationalized. Nowhere is this more visible than in the use of radio by totalitarian regimes. In Nazi Germany, Joseph Goebbels’ Ministry of Propaganda deployed the Volksempfänger, a cheap, mass-produced radio with limited tuning capacity, to control the ideological environment. This device ensured that only state-approved broadcasts could be heard, effectively turning the home into an extension of the Reich.4

This was not simply censorship; it was technological encirclement. By restricting user agency through the design of the machine itself, the regime converted radio from a medium of information into a mechanism of uniformity. The fraud here was structural, not performative. Listeners were not misled by what was said alone, but by the illusion that they were freely listening.

The machine, again, was complicit. Its design participated in the deception, not as a passive carrier but as an active gatekeeper. In doing so, it challenged Enlightenment notions of technology as neutral. In this case, the machine was built to deceive, and its success was measured in ideological conformity.

Radio in Wartime America: The Rhetoric of Unity

While the overt propaganda of fascist regimes is well known, it is important to recognize that Allied powers, including the United States, also harnessed radio for ideological purposes during World War II. In America, programs such as Voices of America, Command Performance, and This Is War! used the medium to cultivate patriotism, reinforce trust in leadership, and bolster morale. These broadcasts presented war as a moral crusade, often glossing over the complexities of foreign policy or battlefield ambiguity.5

Though not fraudulent in the sense of deliberate falsehoods, the messages were highly curated. Technology again served as a selective filter, amplifying unity while muting dissent. Radio’s intimacy, the way it entered homes, spoke in trusted tones, and shaped nightly routines, made it an ideal vehicle for ideological smoothing. The deception was not always in what was said, but in what was omitted.

Cold War Theater and the Absurdity of Surveillance

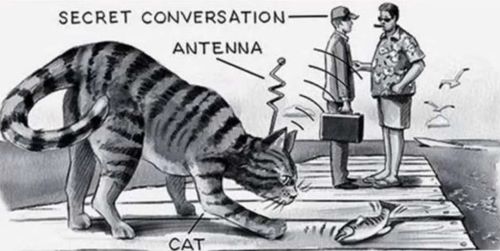

Implanted Cats and Disguised Cameras

The Cold War, with its paranoia and technological brinkmanship, produced some of the most surreal intersections of science and absurdity. Among these was the CIA’s “Acoustic Kitty” project, a classified attempt to implant listening devices into cats for use in espionage operations. While the project ended in failure, reportedly after the first cat was killed by traffic, the sheer scale and seriousness of the endeavor reveal a profound faith in technological deception.6

Other surveillance devices, such as cameras hidden in cigarette packs or microphones in pens, contributed to an aesthetic of omnipresent observation. These tools were often less effective than imagined, but their symbolic power lay in the suggestion that no space was safe from infiltration. The deception here operated in two directions: outward toward enemy surveillance, and inward toward a public whose sense of reality became increasingly shaped by suspicion.

The Quiet Listener: Wiretapping and the Illusion of Legality

Wiretapping emerged in the 20th century not merely as a tool of espionage, but as a contested site of legal and ethical ambiguity. In the United States, federal agencies including the FBI used wiretaps extensively, often without warrants, during periods of political unrest and perceived national threats. The technology allowed for real-time access to private conversations, transforming the telephone, once a symbol of domestic intimacy, into a potential vector of state intrusion.7

What made wiretapping uniquely deceptive was its invisibility. Unlike hidden microphones or trailing agents, the act left no trace. Its effectiveness lay in the illusion that communication was secure. That illusion, once pierced by scandal or revelation, often sparked deep public distrust. The deception was not only technical, but moral: it hinged on the unspoken assumption that those listening had the right to do so.

Scientific Pseudomachines and Institutional Credulity

Reich’s Orgone and the Machinery of Cosmic Fraud

One of the more eccentric figures of 20th-century pseudoscience, Wilhelm Reich, developed a device he claimed could collect and amplify “orgone, a cosmic life energy he believed permeated the universe. His “orgone accumulator” resembled a wooden cabinet lined with metal and insulation, in which users were instructed to sit in order to receive healing effects. Reich’s theories had no scientific basis, but the machinery surrounding them was persuasive to a number of followers.8

Despite eventual prosecution by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the destruction of his devices by court order, Reich’s work demonstrates how pseudoscience can be dressed in technological clothing to gain legitimacy. His machines gave form to metaphysical nonsense, allowing the invisible to masquerade as measurable. In this case, the deception was not merely interpersonal but institutional, enough to provoke federal intervention.

The Polygraph and the Performance of Truth

Few devices in modern history better embody the convergence of faith in technology and the longing for certainty than the polygraph. Designed to detect deception by measuring physiological responses such as heart rate, respiration, and galvanic skin response, the polygraph gained rapid popularity in criminal justice and employment settings. It promised an objective window into human truthfulness, a machine that could read the soul through the skin.9

Yet scientific consensus has never fully embraced the polygraph as reliable. Critics point to the variability of stress responses and the ease with which results can be manipulated or misinterpreted. Still, the machine persists in legal and cultural arenas, a testament not to its accuracy but to its aura. The polygraph performs truth as spectacle. It deceives not by error alone, but by the confidence it inspires in those who seek easy answers to complex motives.

Conclusion: The Machine as Mirror and Mask

The story of modern technology is often told as one of forward motion—of invention, acceleration, and mastery. But as this essay has shown, progress is rarely linear and never morally neutral. The same engines that powered innovation also animated illusion. From the clockwork charm of 19th-century automata to the cold circuitry of 20th-century surveillance, machines have not only extended human reach—they have obscured it, redirected it, and, at times, betrayed it.

What unites these episodes is not simply deception, but complicity: the public’s willingness to believe, institutions’ eagerness to endorse, and technology’s peculiar ability to cloak artifice in the language of precision. Whether through the theatrical automatons of the Victorian stage, the pseudoscientific facades of phrenological and orgone machines, or the silent listening devices of authoritarian regimes, we confront again and again the same paradox—our faith in the machine often exceeds the machine’s truth.

These are not historical curiosities; they are warnings written in wire and wood, brass and broadcast. To study the craft of technological deception is not to reject innovation, but to better understand its cultural metabolism—the way belief, authority, and desire move through circuits and screens. The allure of the machine endures not because it is always honest, but because it so convincingly pretends to be.

And perhaps that is the most powerful illusion of all.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Tom Standage, The Turk: The Life and Times of the Famous Eighteenth-Century Chess-Playing Machine (New York: Walker & Co., 2002).

- Sherrie Lynne Lyons, Species, Serpents, Spirits, and Skulls: Science at the Margins in the Victorian Age (Albany: SUNY Press, 2009), 95–98.

- Ibid., 103–107.

- David Welch, The Third Reich: Politics and Propaganda (London: Routledge, 2002), 67–70.

- Gerd Horten, Radio Goes to War: The Cultural Politics of Propaganda during World War II (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 21–47.

- Victor Marchetti and John D. Marks, The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence (New York: Knopf, 1974), 112–116.

- David Greenberg, Republic of Spin: An Inside History of the American Presidency (New York: W.W. Norton, 2017), 281–289.

- James E. Strick, Wilhelm Reich, Biologist (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015), 203–218.

- Ken Alder, The Lie Detectors: The History of an American Obsession (New York: Free Press, 2007), 57–94.

Bibliography

- Alder, Ken. The Lie Detectors: The History of an American Obsession. New York: Free Press, 2007.

- Greenberg, David. Republic of Spin: An Inside History of the American Presidency. New York: W.W. Norton, 2017.

- Horten, Gerd. Radio Goes to War: The Cultural Politics of Propaganda during World War II. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

- Lyons, Sherrie Lynne. Species, Serpents, Spirits, and Skulls: Science at the Margins in the Victorian Age. Albany: SUNY Press, 2009.

- Marchetti, Victor, and John D. Marks. The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence. New York: Knopf, 1974.

- Standage, Tom. The Turk: The Life and Times of the Famous Eighteenth-Century Chess-Playing Machine. New York: Walker & Co., 2002.

- Strick, James E. Wilhelm Reich, Biologist. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015.

- Welch, David. The Third Reich: Politics and Propaganda. London: Routledge, 2002.

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.31.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.