Belief across various settings and platforms varied enormously.

By Dr. Eleanor Dobson

Associate Professor in Nineteenth-Century Literature

University of Birmingham

Introduction

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.1

Throughout the nineteenth century and beyond, city centres saw the side-by-side existence of all varieties of spectacle for the purposes of entertainment, scientific or spiritual demonstration. This article explores the crossover between ancient Egypt, magic and illusion, with tropes and conventions exchanged between a variety of discourses that thrived, especially in metropolitan spaces: stage magic, spiritualist demonstrations, photography and projection technologies leading up to and including early moving pictures. There is a high degree of reciprocity between them, and in turn these media influenced fiction that deals with themes of the supernatural or the illusory in ancient Egyptian contexts. Technologies of magic and illusion were constantly being updated or employed so as to produce new effects, and these developments contributed to the broader association between ancient Egypt and modernity. As Antonia Lant has established, ‘[t]he alliance between optically novel and illusory forms of representation and ideas about Egypt … is detectable at least since the French Revolution and persists throughout the nineteenth century’; there is ‘an imaginative association pulling together the ancient culture and modern spectacular invention’ evident ‘across lantern shows, panoramas, dioramas, photographs … and on into the emerging sphere of cinema itself’.2 Expanding Lant’s understanding of these technologies’ enduring association with antiquity, this article posits the indelibility of the association between ancient Egypt and magic (both illusory and occult power) as vital to Egypt’s continued relevance as visual subject matter to be rendered on stage sets, in photographs and projected as ethereal light.

First, this article investigates the significance of London’s Egyptian Hall, a popular entertainment venue, in aligning ancient Egypt with cutting-edge optical effects and magical technologies, leading to a closer examination of the exchanges between the spiritualist séance and stage- magic performances (both of which were performed at the Egyptian Hall across its history) in media of the age. Whether stage conjuring or purportedly genuine occult ritual, the apparitions and mysterious lights, sounds and sensations associated with these performances found their counterparts in written descriptions of ancient Egyptian magic. When we look to representations of genuine ancient Egyptian magic in fiction, and to instances of Egyptian- themed optical illusion and spectacular trickery, we see authors – notably E. Nesbit and the magician Henry Ridgely Evans, in fiction and nonfiction – playfully blur the lines between these categories. Nesbit and Evans, in their interest in the Egyptian Hall respond to a particularly potent popular reference point in the visual culture of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century magic, infusing this venue famous for its performers’ optical trickery with a keen sense of genuine supernatural power.

The article moves on to discuss optical technologies that were supposedly used to capture spirit materialisations – namely, photography – and the technologies of entertainment which created and projected luminous images. These include the magic lantern and early moving picture cameras, the Egyptian Hall being the second venue in Britain (by a matter of days) to show projected moving pictures. Such technologies may well have appealed to rapt audiences through their innovations, yet, as we shall see, they also facilitated imaginative access to antiquity on a hitherto unrealisable scale; photography, in particular, promised to facilitate personal creative engagements with ancient Egypt in which one could assume an ancient Egyptian identity in the guise of a mummy or a sphinx, while other photographs apparently captured glimpses of genuine Egyptian spirits. In. H. Rider Haggard’s historical novel Cleopatra (1889) the rites of Isis appear half séance, half magic-lantern display, while other texts that depict Egyptian magic also turn to the spectacle of the panorama or phantasmagoria (magic- lantern shows featuring dynamic effects) to aid readers in visualising Egyptian magic. Notably, such metaphors and similes were exploited by stage magicians and occultists alike, magician Henry Ridgely Evans and occultist Charles Webster Leadbeater among those turning to the same language of visual theatrics, juxtaposing modern and ancient in their fictional descriptions of primeval landscapes, supernatural powers, and their psychological effects in relation to up-to-date optical techniques.

The final sections of the article turn to dissolve techniques, used in magic- lantern displays but also integral to an understanding of the depiction of supernatural materialisations and transformations in early film. In Marie Corelli’s Ziska, the novel’s climax deep within a pyramid sees the ancient Egyptian woman metamorphose from woman to translucent spirit, while the short moving pictures of filmmakers with links to the Egyptian Hall also use ancient Egypt as an immediate visual marker for magic. Artefacts and individuals hailing from Egypt are, in these works, impossible to pin down, shifting, vanishing and re- emerging in depictions of supernatural powers effected entirely by new technological possibilities. As this article draws to a close, we find ourselves back at the Egyptian Hall, underscoring its centrality to the visual culture of magic, its importance in histories of spectacular and technological innovation, and the windows to the ancient world that such venues, their performers and apparatus conjured up.

Before turning to the Egyptian Hall, it is useful to ascertain a sense of the range of magical activities whose practitioners emphasised their associations with ancient Egypt. Karl Bell’s understanding of the magi-cal imagination is useful here, which he specifies ‘not only embod[ies] specific magical practices such as witchcraft and astrology, but also encompass[es] a fantastical mentality informed by supernatural beliefs, folkloric tropes, and popular superstitions’.3 Bell’s examples from the latter half of the nineteenth century are particularly intriguing for their intertwinement with Egyptian imagery; these ‘[l] ater Victorian expressions of “magical” mentalities’ include ‘spiritualism, the stage shows of Jean Eugene Robert- Houdin or John Maskelyne, “Pepper’s Ghost”, [and] the occult activities of the Order of the Golden Dawn’.4 Bell ultimately contends that ‘the magical imagination testifies to the previously underestimated extent of genuine belief in the fantastical in the nineteenth century’.5 Belief across these settings varied enormously, of course. Spiritualist séances were held to manifest genuine supernormal phenomena by some, though others approached these occasions with more scepticism; others still chastised mediums for what they held to be outright charlatanerie. Stage-magic shows often involved the magician’s assertion that what audiences witnessed was real; and while many (if not most) audience members believed that what they observed was exclusively illusory, they nonetheless indulged in the pretence of the magician’s claims to the contrary (a mentality that has been termed the ‘ironic imagination’ by Michael Saler).6 The Golden Dawn, meanwhile, a secret society devoted to occult practices, sincerely pursued the paranormal at the fin de siècle. What I seek to add to Bell’s work on this variety of contexts that invited and facilitated the magical imagination is ancient Egyptian iconography’s usefulness as a kind of shorthand for magic, not just in settings reliant upon an atmosphere of occult gravitas as in the Golden Dawn’s rituals, but equally in settings where cutting-edge technological innovations were being showcased and in which the magical atmosphere necessitated the suspension of disbelief. In each case, Egypt aided in establishing an air of authenticity. The Egyptian Hall’s role in encouraging this, as a site where past and present met in nineteenth- and early twentieth- century culture, was crucial.

The Egyptian Hall

If ancient Egypt was customarily held as the source of ritual magic, then it was equally considered the place where illusory stage magic originated. As with histories of occult power, common to many nineteenth- century books on illusion is the claim – usually in the introduction – that its roots were in antiquity, most often in Egypt itself. The Boy’s Own Conjuring Book: being a complete handbook of parlour magic (1859), for instance, relates that ‘sleight of hand … and various miraculous deceptions, were the means by which the priests of Egypt, Greece, and Rome, used to subjugate mankind’.7 That the ancient Egyptians who honed these illusory skills belonged to the priesthood is a fairly common assumption, their craft purportedly employed for the purposes of tricking laypeople into believing that the gods were performing miraculous feats or granting the priests supernatural powers. Magic is cast in such volumes not as a potent force, but as deceptive trickery involving legerdemain, misdirection and optical technologies. For residents of London across the nineteenth century, the Egyptian Hall reinforced the close association between ancient Egypt and illusion outlined in such publications.

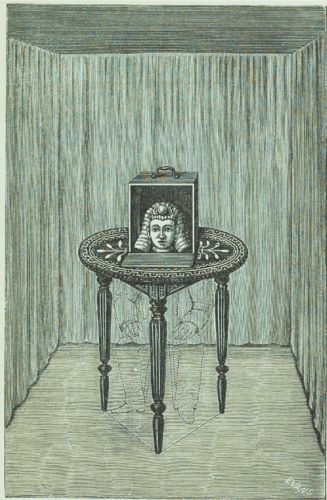

The Egyptian Hall (figure 1.1) in Piccadilly was England’s first major public building with a neo-Egyptian façade, its distinctive frontage inspired by the temple of Hathor at Dendera.8 Built in 1812, the Egyptian Hall was an ethnographical and natural history museum until 1819, subsequently housing art exhibitions, panoramas, spiritualist performances and, eventually, anti- spiritualist demonstrations, illusion and moving picture shows, before its demolition to make way for flats and offices in 1905. Its distinctive Egyptianised aesthetic imparted some-thing of antiquity’s glamour onto what took place within, as was the case with other London venues that drew upon ancient Egypt in their décor. Ancient Egyptian iconography suffused the city’s meeting spaces used by the Freemasons, who had promoted their connection with ancient Egypt since the latter half of the eighteenth century.9 In the nineteenth century’s closing decades, newer occult orders such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn would also meet in Egyptianised settings.10

The Egyptian Hall’s Orientalised style (not authentically ancient Egyptian, but a fantastical interpretation loosely informed by archaeological sources) was sometimes mirrored in the acts and exhibitions it housed. Early in its history, in 1821, it was the venue for the Italian circus-strongman-turned-explorer Giovanni Battista Belzoni’s (1778– 1823) exhibition of the tomb of Seti I, an immersive recreation of Egyptian spaces, replete with mummified remains that Belzoni had transported from Egypt. Subsequently, the Hall was home to many exhibitions without an overt Egyptian connection. It was after the mid-point of the nineteenth century that the Hall became strongly associated with both spiritualist performances and stage magic, and when a relationship between the Hall’s exterior and what took place within began to be re- established. An illusion by the name of Stodare’s Sphinx, for example, first performed by the British magician Joseph Stoddart (1831– 66) in 1865, drew upon ancient Egypt’s mysterious aura. The trick involved the use of angled mirrored glass to make the head of the magician’s accomplice, enclosed within a box and topped with a kind of nemes headdress (symbolic of royalty), appear dismembered. The ‘Sphinx’ would open its eyes, answer questions posed by Stodare (Stoddart’s stage persona), and recite poetry, after which Stodare would close the box. Stodare would next reveal that his ability to ‘revivify … the ashes of an ancient Egyptian, who lived and died some centuries ago’ only lasted for 15 minutes before the Egyptian must return to dust; he would then open the box to reveal a pile of ash.11 Charles Dickens (1812– 70) saw the illusion and praised it for being ‘so extraordinarily well done’.12 The trick was evidently impressive enough to have been deemed fit for the eyes of Queen Victoria and her children that same year; of the illusions performed by Stodare, the Sphinx was one of two to receive an encore from the royal family.13 Stodare’s illusion was so celebrated that a diagram of the trick appears as the first image in several guides to magic of the latter half of the nineteenth century (figure 1.2), notably being reprinted over the course of at least 16 editions of Louis Hoffmann’s (1839– 1919) Modern Magic: a prac-tical treatise on the art of conjuring, which first appeared in 1876, stretching to editions appearing as late as the 1910s.14

The American magician Henry Ridgely Evans painted a vivid picture both of Stodare’s Sphinx and the Egyptian Hall in his magical history, The Old and the New Magic (1906), published the year after the Egyptian Hall’s demolition:

What is the meaning of this Egyptian Temple, transplanted from the banks of the Nile to prosaic London? The smoke and grime have attacked it and played sad havoc with its sandstone walls, painted with many hieroglyphics. The fog envelops it with a spectral embrace … The temple … is guarded by two up-to-date, flesh-and-blood Sphinxes in swallow-tail coats and opera hats … See the long line of worshippers waiting to obtain admission to the Mysteries. Has the cult of Isis and Osiris been revived?15

In this passage, Evans evidently enjoys stage magic’s tongue-in-cheek claims to be genuine, the theatricality of its venues, and indeed the suspension of disbelief, imagining what transpires within the Hall to be real. The Egyptian Hall was by no means a convincing Egyptian temple – at least to early twentieth- century onlookers in the final years of the Hall’s existence; its hieroglyphs were nonsense signs (major breakthroughs in decipherment were made a decade after the Hall was constructed) and the statues of Isis and Osiris were executed in a style that was far from Egyptianate. Nevertheless, Evans revels in imagining the Egyptian Hall as an authentic temple for the best part of a page, before going on to explain the illusion behind Stodare’s Sphinx. More than 40 years after Stodare’s illusion was performed, and even once the Egyptian Hall itself had ceased to stand, this famed optical trick is most dramatically imagined – in Evans’s work at least – after an evocation of the enchanting atmosphere of the Egyptian Hall.

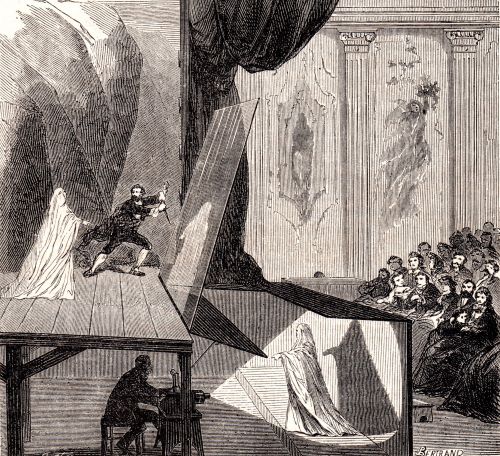

While many illusionists brought Egyptian elements into their performances – the scientist Gertrude Bacon (1874– 1949) records in an article on the Hall’s history that ‘the Fakir of Ooloo, Hermann [sic], and Dr. Lynn, well- known conjurers of their day, strove to introduce Egyptian Magic into the London temple of Isis and Osiris’16 – even illusions with-out their own obvious Egyptian connections were marketed using the imagery of ancient Egypt. One of the most influential illusions in the nineteenth century (still in use today) was the British scientist and inventor John Henry Pepper’s (1821– 1900) ‘Pepper’s Ghost’. The trick is based on reflections in angled glass, a translucent image appearing and disappearing as a light source brightens and dims. Pepper’s Ghost began as an optical illusion used for scientific demonstrations, before finding its way into theatrical and magical performances.

Pepper first exhibited his Pepper’s Ghost at the Royal Polytechnic Institution, then under his own management, before taking the illusion to the Egyptian Hall. The programme for Pepper’s show from 1872 employs ancient Egyptian imagery in keeping with this new setting; it features a face wearing a nemes headdress and hands emerging from a cloud of dark smoke that pours forth from a lit amphora.17 With a background sporting the pyramids of Giza, the programme draws upon ancient Egypt’s reputation for the mystical, situating Pepper’s performance within two magical traditions: one that claims to be able to produce ‘true’ supernatural magic, and the other that promises to delight – or to deceive – with illusion or legerdemain. Emblazoned with a ribbon declaring the title of Pepper’s performance as ‘The new and the wonderful!’, the programme makes explicit the tension between novelty and ‘newness’ in the programme’s text, and antiquity and ‘old-ness’ in its visual imagery. Inside the programme, the running order begins with a lecture ‘On some of the Realities of Science’, underneath which are listed Pepper’s academic credentials to bolster his credibility as a man of science: ‘Fellow of the Chemical Society; Associate of the Institution of Civil Engineers; Hon. Diploma in Physics and Chemistry of the Lords of the Committee of Council on Education; late Professor of Chemistry and Honorary Director of the Royal Polytechnic Institution.’ After readings from famous dramatic and poetic works by another performer, an interval and a musical interlude, ‘Professor Pepper’s Ghost’ illusion featured as part of a ‘historical and dramatic sketch’ promising ‘Scenic and Spectral Effects’. Such details demonstrate that even while the cover of the programme entices with imagery of ancient Egypt – the birthplace of magic(s) – this is not at the expense of underlining that the illusion, and the individual performing it, are, first and foremost, aligned with science.

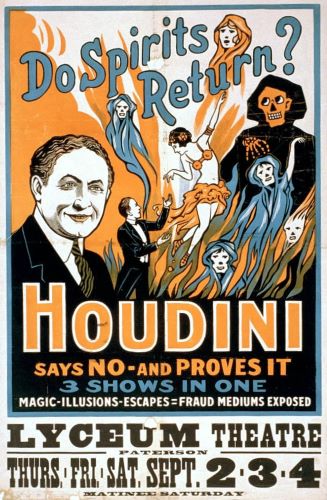

From 1873, the British magicians John Nevil Maskelyne (1839– 1917) and George Alfred Cooke (1825– 1905) performed shows at the Egyptian Hall that exposed the mechanisms behind faked spiritualist phenomena, breaking down the boundaries between illusory and super-natural categories of magic.18 As Catherine Wynne elegantly puts it, in Maskelyne and Cooke’s shows, ‘[s]cience and séance converged on the late Victorian stage’.19 The kinds of activity that Maskelyne and Cooke attempted to replicate and explain were the most sensational wonders of the séance, summarised by author and prominent member of the Society for Psychical Research, Frank Podmore (1856– 1910):

Inexplicable sounds; the alteration of the weight of bodies; the movement of chairs, tables and other heavy objects, and the playing of musical instruments without contact or connection of any kind; the levitation of human beings; the appearance of strange luminous substances; the appearance of hands apparently not attached to any body; writing not produced by human agency; the appearance of a materialised spirit-form.20

Like Pepper’s before them, the programmes for Maskelyne and Cooke’s debunking performances, which ran from 1873 to 1904, often emphasised the ancient Egyptian architectural style of the Hall – imagery of gods, goddesses, flaming torches and coiled serpents – rather than the kinds of illusion that they actually produced in their shows.21 This, along with the Hall’s architecture, lent an exotic tone to the proceedings.22 The pylon- shaped architrave at the building’s entrance, reproduced on some programmes, evokes an Egyptian temple, and so passing over this threshold, in reality or in the turning of the programme’s page, appeals directly to the magical imagination.

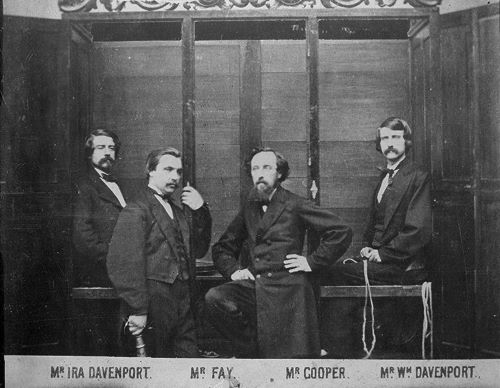

While geographically confined to a fairly affluent area of London, the Egyptian Hall’s cultural impact was such that ripples of its influence could be felt across the Atlantic Ocean. The American magician Harry Kellar (1849– 1922), who had previously worked with the infamous Davenport brothers fraudulently producing spiritualist phenomena (which they had performed at the Egyptian Hall), was so inspired by this venue that he gave the name to his own theatre, housed in a Masonic Temple on Philadelphia’s Chestnut Street.23 Kellar’s Egyptian Hall was only active from 1884 to 1885 before he left Philadelphia. Upon his return, he found that his Hall had burned down, prompting him to open a second Egyptian Hall on the same street in 1891.

Posters of Kellar represent him alongside recognisable ancient Egyptian symbols and scenery. One depiction of his ‘Levitation of Princess Karnac’ illusion in the early 1900s (inspired by a levitation trick he saw performed by Maskelyne at the Egyptian Hall), features the pyramids in the background, while Kellar himself stands at the top of the steps approaching a pylon- shaped temple and flanked by twin sphinxes.24 An assistant in exotic costume floats in the air in a reclining position before him. Another version of the poster shows him with a far more detailed background featuring seated colossi evocative of those of the Great Temple of Ramses II at Abu Simbel or perhaps the Colossi of Memnon, handily relocated to a position adjacent to the Sphinx so as to form a composite image of Egypt at its most monumental.25

Kellar was one of the most successful magicians of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and the Egyptian Hall’s iconography, by which he was so influenced, was in turn inherited by his successors and emulators. The ‘Levitation of Princess Karnac’ illusion was passed down by Kellar to Howard Thurston (1869– 1936) and duplicated by Charles Joseph Carter (1874– 1936), both of whom drew upon ancient Egypt’s glamour in advertisements for their own shows. Carter advertised his levitation trick in the early 1900s using a design based heavily on one of Kellar’s.26 A poster of Thurston from around 1914, meanwhile, shows an ancient Egyptian-inspired stage set featuring technicolour columns and a gilded cabinet into which a boy and girl (in ancient Egyptian- themed costume) – along with a donkey – enter and vanish.27 Atop the cabinet is a winged solar disc, giving the structure the appearance of a miniature temple. The apparatus was, likely, a large-scale version of Stodare’s Sphinx.28

Another Egyptian Hall appeared in 1895 when a small theatre of this name was built in Ohio by the American politician and magician William W. Durbin (1866–1937). The theatre would go on to become a magic museum and was the site of the first ever convention devoted to magic in 1926. In the years after the demolition of London’s Egyptian Hall in 1905, then, its influence still resonated with some of the most celebrated magicians of the early twentieth century; it survived, too, in various other Egyptian Halls that sought something of the original’s cultural success. Intriguingly, it is in the aftermath of London’s Egyptian Hall’s demolition that we see authors specifically drawing upon this venue when describing genuine Egyptian magic in their texts, once it, like ancient Egyptian civilisation before it, had become consigned to the past. Literary allusions attest to its ever- presence in the Edwardian magical imagination, however. The effect is a curious blending of real magic and trickery, which mirrors the Egyptianised programmes advertising the shows of Pepper, and Maskelyne and Cooke.

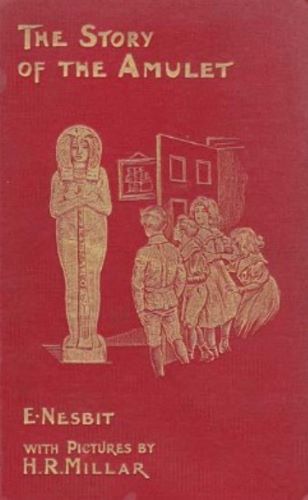

For example, when the children in E. Nesbit’s The Story of the Amulet (1906) – first serialised in The Strand Magazine as The Amulet: a story for children between 1905 and 1906 – seek entertainment towards the novel’s end, they set off for ‘the Egyptian Hall, England’s Home of Mystery’, for ‘[a]ll children, as well as a good many grown- ups, love conjuring’.29 But when they arrive in Piccadilly they cannot see the ‘big pil-lars outside’; the Egyptian Hall, demolished in 1905, temporally eludes the time- travelling children, and after a policeman informs them of the whereabouts of Maskelyne and Cooke’s new premises – St George’s Hall in Langham Place – they finally enjoy ‘the most wonderful magic appearances and disappearances, which they could hardly believe – even with all their knowledge of a larger magic – was not really magic after all’.30

While Nesbit’s Edwardian protagonists are not granted an encounter with the Egyptian Hall itself, they do witness a performance by the magician David Devant (1868– 1941), a member of Maskelyne and Cooke’s company, at which an ancient Egyptian priest, Rekh- marā, materialises. Devant witnesses the sudden appearance of the Egyptian priest amidst his audience and smoothly incorporates this into his own show:

Though the eyes of the audience were fixed on Mr David Devant, Mr. David Devant’s eyes were fixed on the audience … So he saw quite plainly the sudden appearance, from nowhere, of the Egyptian Priest.

‘A jolly good trick,’ he said to himself, ‘and worked under my own eyes, in my own hall. I’ll find out how that’s done.’ He had never seen a trick that he could not do himself if he tried.

By this time a good many eyes in the audience had turned on the clean-shaven, curiously-dressed figure of the Egyptian Priest.

‘Ladies and gentlemen,’ said Mr Devant, rising to the occasion, ‘this is a trick I have never before performed. The empty seat, third from the end, second row, gallery— you will now find occupied by an Ancient Egyptian, warranted genuine.’

He little knew how true his words were.31

While the Egyptian Hall is gone, the Egyptianised trappings of stage magic persisted, and so Rekh- marā, ‘curiously dressed’, is not out of place in the modern magic venue: in fact, his costume marks him out as stage-magical. The moment is redolent of Henrietta Dorothy Everett’s novel Iras, A Mystery (1896), published under the pseudonym Theo Douglas, in which the narrator is invited to attend an event where a fortune teller is to provide the entertainment and, before the proceedings begin, finds his ‘attention … arrested by a totally unexpected figure’: ‘a man in the sacerdotal costume of ancient Egypt’.32 With no clear explanation as to the man’s identity, the narrator’s friend suggests that he might be ‘some satellite’ of the fortune teller, and so the narrator – a sceptic – expects to ‘discover him … in conjunction with the rest of the diablerie’.33 Ancient Egyptian costume is misleading in both Nesbit’s and Everett’s texts, falsely indicating stage magic rather than the genuine occult power accessible to both of these ancient Egyptian priests. In Nesbit’s novel, although Devant does not realise it, this is the first ‘jolly good trick’ he sees that he cannot replicate himself.

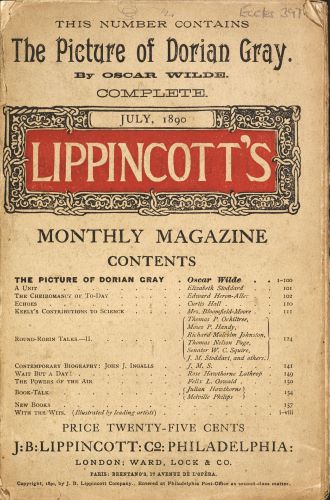

Egyptian magic in The Story of the Amulet as a whole is, after all, ritualistic and supernaturally powerful, rather than mundane productions of spectacular illusory effects. Rekh-marā threatens, ‘I can make a waxen image of you, and I can say words which, as the wax image melts before the fire, will make you dwindle away and at last perish miserably’.34 Dedicated to E. A. Wallis Budge (1857– 1934), then Keeper of the Department of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities at the British Museum, Nesbit’s novel integrates much that was considered Egyptologically accurate at the time she was writing, and Nesbit’s detail about the employment of wax in magic echoes details from Budge’s book Egyptian Magic (first published in 1890, but which appeared in several later formats). Budge notes ‘that the use of wax figures played a prominent part in certain of the daily services which were performed in the temple of the god Amen- Ra at Thebes’ and ‘that these services were performed at a time when the Egyptians were renowned among the nations of the civilized world for their learning and wisdom’.35 The parallels indicate that the detail of Egyptian magic involving wax figures certainly came from Budge, and that Nesbit’s anchoring of the magic that Rekh-marā claims to be able to enact in historical fact attests to its authenticity.

The sinister threat of the Egyptian priest’s claim is undercut, how-ever, by his awe at one of the children, Cyril, being able to ‘make fire itself’ through the use of a modern matchstick, a moment illustrated in the serialised version of the text that depicts Rekhmarā shrinking back into the shadows, away from this symbol of modernity.36 Nevertheless, the text does not disprove the veracity nor indeed the potency of genuine Egyptian magic, even when faced with the stagier gimmicks of the children’s supposedly magical productions. Indeed, when the children perform other acts of magic to dazzle the ancient Egyptians, they are simply employing the titular Egyptian amulet (as anyone with the ‘word of power’ could) to travel through time and space, making it seem as if objects are instantaneously appearing (using the amulet rather like an enchanted trapdoor). Through this method they produce ‘a magic flower in a pot’,37 presumably a tongue- in- cheek reference to stage magicians’ production of bouquets of flowers as if out of thin air (usually with the apparatus concealed up their sleeve). Intriguingly, the manifestation of flowers – including plants replete with pots – was also popular in spiritualist séances; in 1890 the medium Elizabeth d’Espérance (1855– 1919) materialised a potted lily, seven feet in height, and with a piece of mummy bandage impaled by its stem, confirming – so d’Espérance claimed – that the plant had come to the séance directly from Egypt.38

There is certainly irony in that the children’s production of fire from a match is considered to be the result of genuine supernatural power, while the creation of an archway to their own time via the amulet is held to be nothing more than a ‘conjuring trick’, specifically one produced by ‘[s]ome sort of magic- lantern’ by a woman that they meet in the future.39 Indeed, there is comedy in the frequent misunderstandings as to what type of magic is being witnessed by the novel’s various audiences. When the Queen of Babylon wishes that the Babylonian artefacts in the British Museum ‘would come out … slowly, so that those dogs and slaves can see the working of the great Queen’s magic’, the smashing of the glass display cases and the artefacts ‘floating steadily through the door’ is not effected through her magic at all (she does not display any magical abilities of her own throughout the text), but the work of the wish- granting sand fairy, the Psammead. When a journalist assumes the Queen to be ‘Mrs. Besant’ and the sight he witnesses to be the result of ‘theosophy’ – a reference to the British theosophist Annie Besant (1847– 1933) – the range of magical possibilities is broadened further still, expanding to the powers claimed to have been developed by key players in the occult revival.40

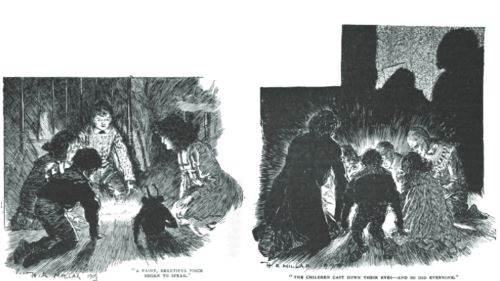

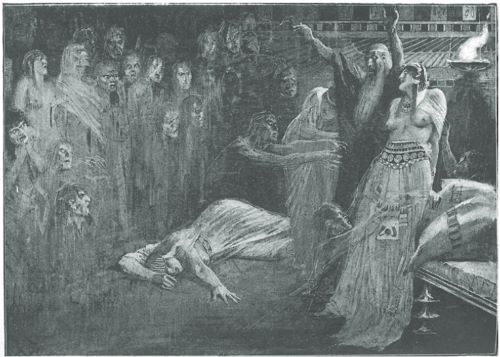

Other representations of Egyptian magic in the novel suggest séance- like activities, as when the children ‘prepare the mystic circle and consult the Amulet’.41 Such moments are categorised by ‘a silence and a darkness’ out of which emerges ‘a light and a voice’.42 The children ask questions of the voice – implied to be that of the goddess Isis – and the voice answers, granting, at the novel’s conclusion, a spiritual union between a modern Egyptologist and the ancient Egyptian priest in something akin to a wed-ding ceremony, as they join hands underneath an arch illuminated by celestial radiance. Nesbit’s repeated simile of magical conjoining – ‘as one quick-silver bead is drawn to another quick-silver bead’43 – under-lines this union’s alchemical associations, and so alchemy too is subsumed into the novel’s broader magical melting pot. Séance-like images of the magical use of the amulet bookend the first and final instalment of the narrative as it first appeared in The Strand Magazine (figure 1.3). This version of the text visually represents the darkness in which the amulet operates, the amulet itself casting a spectral glow onto the faces of the participants who are positioned around it in a circle. In the first image, the children and the Psammead are the participants witness to its magic, while in the second, at the story’s conclusion, they are joined by both the ancient Egyptian Rekhmarā and the modern Egyptologist.44 Ancient Egyptian presences in séances were not uncommon; often, Egyptian spirits were said to have manifested, and several mediums reported having Egyptian spirit ‘controls’ who would help them to open a line of communication with individuals on the other side. Genuine artefacts – and modern forgeries – appeared from out of the gloom and some participants brought ancient Egyptian items with them to the séance, at times to test the abilities of the medium.45 The caption accompanying the first image – ‘A faint, beautiful voice began to speak’ – reinforces the aural as well as visual phenomena that characterise this séance- like experience.

The Story of the Amulet thus presents a varied array of magical activity interpreted as occupying an enormous range of what Bell terms ‘magical thinking’, from optical illusion and stage magic to the spiritualist séance, from theosophy to alchemy. While the Egyptian Hall is aligned in Nesbit’s novel with the first of these categories, Egyptian Hall magicians are also confronted by real ancient Egyptian power that is – to their eyes and to the eyes of audience – merely a magic trick yet to be comprehended.

Published in the same year as the novel version of Nesbit’s text, the British author and explorer George Griffith’s The Mummy and Miss Nitocris: a phantasy of the fourth dimension (1906) similarly features an ancient Egyptian with genuine occult powers, which onlookers compare to Egyptian Hall performances. In this moment, a crowd reacts to the novel’s antagonist, Phadrig, hypnotising the novel’s heroine, Nitocris:

It might have been expected that the miracle, or at least the extraordinary defiance of physical law … would have produced something like consternation among the bulk of the spectators … but they only saw something wonderful … Nothing would have persuaded them that it was not the result of such skill as produced the marvels of the Egyptian Hall.46

This passage in Griffith’s text underscores the Egyptian Hall’s reputation for spectacular visual effects, but it also reads alongside Nesbit’s novel in interesting ways. Phadrig, who was an ancient Egyptian in a former life, uses a genuine occult force in order to coerce Nitocris and, as with the materialisation of Rekh- marā out of thin air in Nesbit’s novel, that this is assumed to be nothing more than an impressive magic trick reveals the indistinguishability of real ancient Egyptian magic and the modern routines that sought to produce similar effects on stage. That Phadrig’s audience includes sceptical professors who ‘each wore the scalps of many spiritualistic mediums’ (one – Nitocris’s father – being a member of the ‘Psychical Research Society’) means that Phadrig is subject to scrutiny that ultimately seeks to determine whether he has genuine occult power or is ‘merely a conjurer’.47 That Phadrig describes the other effects that he can produce in relation to spiritualism and theosophy further recontextualises his powers in relation to the modern world, but also suggests these belief systems as the direct inheritors of genuine ancient occult forces.48 Even after the Egyptian Hall was gone, its legacy was evidently still felt in literature depicting ancient Egyptian magic. The Egyptian Hall, in The Story of the Amulet and The Mummy and Miss Nitocris, is the nearest thing in the crowds’ experience to the real magical abilities that they witness, and is thus emblematic of the meeting point between illusion and genuine enchantment, modern technologies and ancient iconographies.

The Séance and Stage Magic

The séance and stage magic were, in some respects, very similar performances, particularly when stage magic set out to emulate and explain the ways in which certain common séance phenomena could be produced. Peter Lamont claims that nineteenth- century audiences differentiated between the two practices simply by relying on what the conjuror claimed to be able to achieve: direct contact with spirits of the deceased or else illusions and tricks often designed to replicate such acts.49 This was certainly the case in the ‘anti-Spiritualist’ performances by the likes of Maskelyne and Cooke, as well as in the shows of other magicians who explicitly set out to undermine spiritualist mediums’ claims to authenticity. Spiritualists, meanwhile, retorted that magicians were conjuring these effects with real supernatural power without realising or admitting to it.50 Ultimately, while stage magicians’ and spiritualist mediums’ claims varied, as did audiences’ responses to what they witnessed, both kinds of conjuring shared much of the same imagery.

As Michael Saler notes, although stage magic was perceived as something unknowably ancient, it also simultaneously came to express modernity through its fashionability, the audience’s hunger for novelty and new technological developments that facilitated innovative tricks; Karl Bell similarly observes that stage magic ‘promot[ed] bourgeois conceptions of a technological modernity’.51 Of the many features that stage magic and spiritualist séances had in common, ‘innovation and novelty’ were key to the success of both.52 Audiences were eager to see some-thing that they had not experienced before. Nevertheless, the novel was often disguised in such terms as to evoke antiquity: the Ouija board, one method by which the spirits could apparently be contacted, produced at the fin de siècle (first marketed as a game, and subsequently acquiring greater occult credibility), had another name in this period: the ‘Egyptian luck board’.53 While the Ouija board was ‘new’, the suggestion of its origin in Egypt provided it some kind of mystical authenticity.

Often depicted in literature as a curious mingling of the spiritual-ist séance and the stage-magic performance, demonstrations of ancient Egyptian occultism relate back to contemporaneous notions of illusion, with traces of novel tricks and phenomena essential to securing the reputation of the medium or stage magician. Intriguingly, the blending of these types of magical performance means that the ‘genuineness’ of the phenomena remains hazy for original readers and those encountering the texts now; is the Egyptian magic presented in these narratives real or merely an optical effect? Is this an occult achievement or a scientific one? In most cases, it appears to be both, occupying an alchemical middle ground.

Myriad texts that feature ancient Egyptian magic blend the supernatural with the theatrical in this way. H. Rider Haggard provides a compelling case study, his own texts having made a particular impact upon the world of stage magic and other kinds of illusory performance.54 In his novel Cleopatra (1889), the protagonist Harmachis communes with the goddess Isis, who appears before him as a ‘dark cloud upon the altar’ that ‘grew white … shone, and seemed at length to take the shrouded shape of a woman’.55 Surrounded by ‘bright eyes’, ‘strange whispers’ and ‘vapours [that] burst and melted’, the descriptions of what Harmachis sees might equally apply to a séance in a fashionable London drawing room or, as David Huckvale suggests, a Masonic initiation ceremony.56 The ancient Egyptian spiritual rite and the cosmopolitan Victorian experience of the supernatural ritual are rendered virtually indistinguishable, particularly through the depiction of the goddess Isis as a ‘shrouded … woman’, suggestive of the manifestation of draped spirit forms in the séance room, or the veiled medium herself.57 Haggard had attended séances in his youth and, although he claimed to have ridiculed these experiences at the time, these events may well have impacted upon the representation of occult practices in his fiction.58 Later, when Isis appears again, she takes the form of ‘the horned moon, gleaming faintly in the darkness, and betwixt the golden horns rested a small dark cloud, in and out of which the fiery serpent climbed’.59 With Isis’s entrance and exit heralded by the music of invisible sistra and her voice emerging from within the smoky cloud, Haggard might be seen to allude to the common séance phenomena of disembodied voices and music (the sistra suggestive of the tambourine, used by many spiritualists), and strange light effects in the darkness.

Harmachis, like the psychic medium, can summon the forms of spirits, requesting that ‘the curtains’ be ‘drawn and the chamber’ ‘a little darkened’, ‘as though the twilight were at hand’ in order to perform his illusion.60 He summons ‘the shape of royal Caesar’ wearing ‘a vest-ment bloody from a hundred wounds’, who materialises first as ‘a cloud’ before taking the shape of a man ‘vaguely mapped upon the twilight, and [which] seemed now to grow and now to melt away’.61 Harmachis makes the image dematerialise after a mere instant, admitting that it was nothing more than a ‘shadow’, an illusory image projected from his own imagination.62 This admission complicates the scene, which here transitions into a kind of anti- spiritualist demonstration. The effects may be convincing, and they may still demonstrate Harmachis’s occult powers, but the conjuror confesses that they are not what they seem.

In keeping with his claim to be an illusionist rather than a medium, Harmachis performs with an ebony wand tipped with ivory, a playful wink to the black and white magic wand that was, by this point, common stage-magic apparatus. This variety of wand was allegedly first used by the French magician Jean Eugène Robert- Houdin (1805–71) in the early 1800s.63 Such a detail would have likely been too glaringly anachronistic to appear in the novel’s rather sombre narrative illustrations by the artists R. Caton Woodville (1856–1927) and Maurice Greiffenhagen (1862–1931), though it does feature in one of the illuminated capitals (figure 1.4) designed by explorer and illustrator Edward Whymper (1840–1911).64 In this image the wand rests atop a scroll inscribed with hieroglyphs. Small stars surrounding and seemingly resting atop the wand suggest a genuine magical power at odds with the depiction of the wand itself. To Haggard’s credit, the ancient Egyptians did use magic wands in their rituals (the earliest surviving examples date from around 2800 BCE) and, while his use of a black and white magic wand is anachronistic, he does take care to describe this relatively modern magical prop as constructed from suitably exotic materials.65 Ancient Egyptian wands were, after all, usually made from hippopotamus ivory.66 Even Whymper’s capital, with its rather curvaceous shape for the capital T it represents,67 is suggestive of the curvature of genuine ancient Egyptian examples rather than the thin straightness of the modern baton, the ram and serpent that make up the ends of this shape evocative of the protective mythical creatures and deities inscribed onto their ivory surfaces. As a result, Haggard – along with one of his illustrators, perhaps in on the ‘joke’ – maintains a degree of historical accuracy, while injecting an element of nineteenth- century stage-magical convention, closely aligning the two.

The history of ancient Egyptian magic had a significant impact on modern magical performances. Both modern stage magic and occult ceremonies inherited a greater sense of legitimacy through their links to ancient Egyptian ritual and illusory conventions, interplay evident not just in Haggard’s novel, but across broader cultural contexts. As Catherine Wynne points out, ‘Victorian [stage] magicians liked to invoke Pharaonic practices’, ‘the period’s excavation of Egyptian tombs add[ing] an occult frisson and contemporaneity to their rituals’.68 While Haggard grants his ancient Egyptian conjuror a modern nineteenth- century magician’s wand, magic wands based on ancient Egyptian iconography were used by nineteenth- century occult groups, including the Golden Dawn, lending their ceremonies a kind of iconographical weight. Haggard’s frame narrative in Cleopatra is one of modern archaeology; opening his novel is an account of how the narrative that follows – a purportedly genuine ancient Egyptian text – had been unearthed and translated. Its revelations of magical rites and demonstrations of illusion in antiquity (which, though the trappings of nineteenth- century stage magic transpire to be surprisingly familiar to Haggard’s readers), establish, from the narrative’s opening pages, a collision between the modern moment and Egyptian antiquity.

Séance phenomena – tempered with the conventions of anti- spiritualist demonstration as theatre – also feature in Everett’s afore-mentioned novel, Iras. Early in the narrative, Ralph Lavenham, a man sceptical about all things paranormal, attends a London soirée where private consultations with a psychic are the evening’s entertainment. The room in which the sessions take place is described as ‘arranged in semi- darkness’, illuminated only by ‘a single lamp with a deep red shade’ and ‘the embers of a dying fire left in the grate’.69 While no psychic phenomena occur in this environment other than some cryptic (but prescient) warnings from the medium, Lavenham sees a man in ancient Egyptian attire elsewhere in the house. Although he assumes the man to be the psychic’s accomplice, the medium discloses that the ancient Egyptian is in fact a spirit that only she and Lavenham are able to see as a result of their clairvoyant powers. The man, Savak, is an ancient Egyptian priest, who reappears multiple times to steal amulets from Lavenham’s ancient Egyptian love interest, Iras, at one point materialising simply as ‘a slender hand’.70 The hand, which has ‘no appearance of detachment … seemed to reach over from behind [Iras] as if the figure to which it belonged were concealed by the back of the sofa, and the arm passed through it’.71 This description conjures up the kinds of techniques used by some of the most famous mediums of the age who claimed to be able to produce the hands of spirits, including the Italian spiritualist medium Eusapia Palladino (1854–1918).72 These phantom appendages were often seen to be detached, when in many cases they seem to have been the hands of the performer, or else a prosthetic that was manipulated to give the appearance of suspension in mid- air. The very idea of furniture with false backs, or which had been otherwise been modified, also suggests the ‘spirit cabinet’ – famously introduced to spiritualist demonstrations by the Davenport brothers, and subsequently used by mediums as (in)famous as Florence Cook (c.1856–1904) – or indeed the duplicate apparatus of anti- spiritualist magicians exposing such phenomena.73 The Davenports’ cabinet featured a hole cut out of the door for the purposes of supplying air to the mediums inside; conveniently, it also offered an orifice through which hands – claimed to be those of the spirits – could emerge. That Savak’s real magic is conceived of as appearing like the fraudulent manifestations of modern mediums casts him as an antagonist. Despite the fact that it is Savak’s occult abilities that allow him to foil Lavenham and Iras’s plans to live as a married couple in the modern world, his powers’ appearance as trickery paints him as one of the deceptive priests who appear at the beginnings of histories of illusory magic; for Savak, like his forerunners, magic is put to nefarious ends: to beguile and to overpower.

This is in direct contrast to Iras, who is presented as a genuine psychic medium, and whose abilities are coded as more passive – therefore more feminine – and put to ends exclusively in pursuit of romantic love and in avoiding Savak’s sinister designs. Iras awakens after having been put into a trance by Savak lasting thousands of years, and this, along with her prophetic dreams about the loss of the amulets on her necklace, indicate that her occult power is connected (unlike Savak’s) to states of unconsciousness. She also reveals to Lavenham that during her life in ancient Egypt she had seen his image ‘in the divining- cup, and in the smoke above the altar’.74 Conjuring images of her lover thousands of years before they meet, Iras has access to genuine future truths, just as the psychic medium at the soirée offers words that predict later events. While Savak’s magic is understood in terms of fraudulent spiritualist illusion, Iras’s is only ever described in terms that suggest a higher power, and ritual magic whose veracity is never in doubt.

To take one final example, Algernon Blackwood’s short story ‘The Nemesis of Fire’ (1908) also adopts the conventions of the séance to depict ancient Egyptian supernatural forces. A member of the Golden Dawn, Blackwood was well acquainted with contemporary ritual magic, especially that which had its roots in ancient Egyptian lore. He was also a theosophist and, as a result, was dedicated to the study of esoteric wisdom passed down from ancient Egypt and India.75 Outside of these quasi-religious organisations, he nurtured a keen interest in the super-natural. He was a member of the Ghost Club and although he was not a member of the Society for Psychical Research, he often participated in their investigations into haunted houses.76 As David Punter and Glennis Byron point out, Blackwood was ‘one of the few writers of Gothic fiction actually to have believed in the supernatural’, and his experiences in these groups that bridged scientific and occult interests had a distinct impact upon his writing.77 His work is laced with traces of authentic mysticism and the modes of scientific inquiry put to use in investigating occultists’ claims, echoing the aims and beliefs of the diverse circles in which Blackwood moved.

In ‘The Nemesis of Fire’, Blackwood describes the materialisation of a fire elemental, which was originally conjured by ancient Egyptian necromancers to protect a mummy. At midnight, the elemental is summoned in a darkened room lit only by red lamps, and provided with an offering of a bowl of blood. Sat at a round table and taking each other’s hands, the participants experience a plethora of typical séance phenomena, beginning with the subtle sensations of the skin being touched with ‘a silken run’.78 Scraps of silk and other light or diaphanous fabrics were often used by mediums to suggest ectoplasm, supposedly a visible spiritual energy that first appeared in the 1880s, while the feeling of being touched (usually on the face or hands) was another common occurrence for sitters.79 One of the characters present, Colonel Wragge, is then possessed by the elemental, his expression changing to one that is ‘dark, and in some unexplained way, terrible’ and speaking with a ‘changed voice, deep and musical’, at once ‘half his own and half another’s’.80 Here, Blackwood draws upon contemporaneous concepts of the supernatural rather than those of ancient Egyptian culture; the ancient Egyptians did not believe in spirit possession, and yet this trope is found in several late Victorian and Edwardian texts with ancient Egyptian supernatural themes.81 In the case of Blackwood’s text, ancient and contemporaneous occultism are brought together, creating a hybrid account of the supernatural in which the ancient world returns via the conventions of modern spiritualist enquiry.

After the Colonel’s possession, ‘a pale and spectral light’ within which can be seen ‘shapes of fire’ begins to materialise from the shadows.82 In the passage that follows, the shapes move and interact with the possessed participant:

They grew bright, faded, and then grew bright again with an effect almost of pulsation. They passed swiftly to and fro through the air, rising and falling, and particularly in the immediate neighbour-hood of the Colonel, often gathering about his head and shoulders, and even appearing to settle upon him like giant insects of flame. They were accompanied, moreover, by a faint sound of hissing.83

The passage reads almost as a catalogue of some of the more impressive séance phenomena of the time. Glowing lights resembling will-o’-the-wisps were part of the repertoires of some of the most notorious psychic mediums, and were sometimes captured in séance photographs. One of the most famous images of a séance, taken by the German psychical researcher Albert von Schrenck-Notzing (1862–1929), seemingly depicts the French spiritualist medium Eva Carrière (1886–1943) with a luminous apparition like a streak of electricity emerging from between her hands. Although the effect was almost certainly the result of a coincidental fault on the film or else the product of subsequent manipulation, photographs showing manifestations of light remained popular because of the compelling nature of the images. Blackwood’s use of lights and also inexplicable sounds – in this case hissing – conforms to accounts of some of the most notorious psychic mediums as investigated and reported on by eminent scientists of the Society for Psychical Research.84 Thus, in his nod to the fraudulent use of fabric to simulate ectoplasm, along with lights and sounds of a more convincing nature, Blackwood combines elements of the séance that hint at fraudulence as much as they gesture to something more genuine.

There are also elements of the theatrical in Blackwood’s text that allude to stage magic, further complicating the representation of the scene. The shape that emerges from the shadows does so ‘as though slowly revealed by the rising of a curtain’, aligning the materialising elemental with the dramatic conventions of the theatre.85 Although curtains were used to drape cabinets in séances, these were meant to shield the medium from view, rather than to be raised dramatically in this manner. Popular visual spectacle and optical technologies are referred to later when the narrator experiences a vision. When he touches the face of the mummy, ‘time fled backwards like a thing of naught, showing in haunted panorama the most wonderful dream of the whole world’.86 The spiritual experience and popular entertainment collide in Blackwood’s narrator’s evocation of the panorama, blending fashionable metropolitan visual spectacle with profound supernatural encounter.

The likening of such a psychic experience to a panorama – which Markman Ellis describes as ‘among the most astonishing and popular of visual spectacles from the early 1790s through most of the next century’87 – further calls into question what is a genuine apparition and what a theatrical visual effect. With its origins in the late eighteenth century, the panorama was an optical technology emblematic of modernity through the various innovations that enhanced the illusion across the nineteenth century. The panorama offered a 360- degree view, essentially being an enormous painting suspended on the inside of a circular room. Dioramas – ‘extensions of the panorama’ that ‘added movement to the image’ – ‘unfolded like a storyboard in time’.88 Of course, Egypt was a popular subject for such entertainments; the Egyptian Hall showcased ‘a moving panorama of the Nile in July 1849’.89 The Grand Moving Panorama of the Nile was ‘conceived and created by Egyptologist Joseph Bonomi (1796– 1872) as a means of introducing people to the scenes and wonders of Egypt, both ancient and modern’. S. J. Wolfe has uncovered that either this same panorama, or a duplicate, was shown in New York before touring America, its afterlife extending into the second half of the nineteenth century.90 Gentle lighting combined with the translucency of the panorama itself gave this particular entertainment an ethereal qual-ity, and its final scene – a fading view of the Great Sphinx of Giza as the lights were dimmed – concluded the spectacle with a dreamlike experience as if travelling back in time from Egypt’s present to its ancient past.

Indeed, decades before Blackwood, otherworldly visions of Egypt were described in relation to the panorama in popular literature. Among them is Grant Allen’s burlesque ‘My New Year’s Eve Among the Mummies’ (1878), published under the pseudonym J. Arbuthnot Wilson. When Allen’s protagonist ‘enters a pyramid only to find ancient Egyptian mummies restored to life, he describes the sight as a ‘strange living panorama’.91 Later, when he commits to be mummified himself so as to spend eternity with the princess Hatasou, he is anaesthetised, and relates that ‘the whole panorama faded finally from my view’.92 Allen’s story, intended as a comic relation of an adventure that his narrator claims to be true, but is, more likely, a vision brought about by malarial fever, uses the panorama as a means to describe a visually exciting experience, alto-gether immersive and dreamlike. Blackwood’s narrator’s relation of ‘time fl[ying] backwards like a thing of naught, showing in haunted panorama the most wonderful dream of the whole world’ reads in a similar way, only with a differing tone to suggest a genuine – rather than dreamed – psychological journey brought about by the ancient Egyptian occult. The narrator’s experience in Blackwood’s text reads very much like The Grand Moving Panorama of the Nile, with its journey back through time to conclude on an image of the distant past. While Blackwood would not have encountered this particular panorama, such technologies evidently made an impression on him, and are evoked again in relation to supernatural Egyptian experiences in his later short story ‘Sand’ (1912), this time set in Egypt itself. His protagonist experiences ‘something swift and light and airy’ flashing ‘[b]ehind the solid mass of the Desert’s immobility … Bizarre pictures interpreted it to him, like rapid snap- shots of a huge fly-ing panorama’.93

The indistinctness of the line between magic and illusion in ancient Egyptian contexts is striking across these accounts. Haggard, Everett and Blackwood seem unable to resist the allure of describing genuine supernatural events in the language of the theatre, with costumes, curtains and specialist props being central to their depictions of the occult. Almost anticipating Hollywood portrayals of ancient Egypt, each more opulent than the last, the rich symbolism, fire, smoke, blood and celestial music of these accounts create a proto-cinematic effect. These writers focus on the multisensory, but particularly on the visual, relating what is seen and what is unseen in terms that describe ancient Egyptian magic in relation to the séance, the anti-spiritualist demonstration, the magic show, and – in Blackwood’s case – the panorama. Magic is thus cast as occupying a hazy middle ground between truth and trickery, genuine manifestation and the products of optics and bespoke equipment. It is to imaging technologies that we now turn in even greater detail, specifically to such apparatus that promised glimpses of the dead.

Phantasmagoria

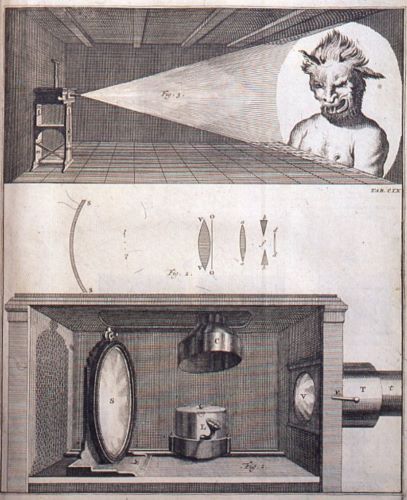

Across the nineteenth century, images of disembodied spirits were produced via ever-changing technologies. Magic lanterns, photographs and, at the end of the century, early moving pictures manifested images of ancient Egypt in various ways and for different purposes, often for entertainments with an emphasis on the magical or supernatural. In turn, the ways in which ancient Egypt was represented by these technologies impacted upon literature; methods of projection, including the magic lantern, are often discernible beneath the text’s surface. Dissolve effects frequently used to depict ghosts in magic- lantern displays, particularly in phantasmagorical shows that relied on more elaborate effects – often involving multiple magic lanterns put to use at once, or the projection of images onto moving surfaces, such as smoke – and, later, film are evoked in literary portrayals of ancient Egyptian characters fading in and out of the material world. We can trace the imagery of such technologies in Haggard and Blackwood, but beyond these authors to fiction including that of the magician Henry Ridgley Evans and the theosophist Charles Webster Leadbeater, too, evidencing how such technologies were employed by those who, respectively, saw Egypt as the origin of optical illusion passing as magic and of genuine supernatural power.

The magic lantern has a history that stretches back to the seventeenth century, though it was not until the eighteenth century that the technology became widely used. That this history was fairly well known did not stop sources such as the children’s penny periodical Young England from recording in 1880 that:

Some suppose that the ancient Egyptians … were the first to use lenses in such a way as to produce effects similar to those now shown with the lantern. No doubt the clever magi, or priests, used to impose upon the poor superstitious people with some kind of mysterious exhibition of shadowy figures.94

The author attributes knowledge of sophisticated illusory effects to the ancient Egyptians, conjuring an image of performance magic facilitated by optical technologies before, ultimately, asserting that ‘[t]he real inventor’ of the magic lantern was, in fact, the German polymath Athanasius Kircher (1602– 80). A reference to similar technologies in ancient Egyptian also exists in the introduction to Henry Ridgley Evans’s novel, The House of the Sphinx (1907); ‘[w]ith the aid of polished convex mirrors of metal’ the ancient Egyptian priests ‘were able to cast image upon the smoke rising from burning incense, and thus often deceived their votaries into the belief that they beheld visions of the gods’.95 Egypt is, once again, imagined as the origin of all things, in this case optical technologies, credited, if not with the invention of the magic lantern itself, then with its precursors.

Ever since the magic lantern’s (true) origins, hand- painted slides had been used to project Gothic subject matter, which likely suggested itself as particularly appropriate imagery given the hazy and luminous effects that the lantern produced, most effective in darkened spaces. These morbid displays evolved into the more complex phantasmagoria from the final decades of the eighteenth century onwards. Painted slides in phantasmagorical displays occasionally depicted ancient Egyptian mummies. Barbara Maria Stafford, for instance, draws attention to the use of the mummy in the phantasmagorical shows of the Belgian magician and physicist Étienne-Gaspard Robertson (1763–1837) in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In these performances, ‘by illuminating a single slide with several candles, Robertson could multiply one figure into many to produce a host of frightening creatures, which he advertised as the “Dance of the Witches” and the “Ballet of the Mummies” ’.96 Some narratives ‘evoked the context of Egyptian archaeology’, one featuring a bejewelled skeleton discovered by a would-be tomb robber.97 Robertson would also move the projectors closer to and further away from projection surfaces, causing the images to shrink or grow. As Marina Warner notes, Robertson’s most successful shows were performed in an abandoned Parisian convent, decorated with hieroglyphs, which he claimed appeared ‘to announce the entrance to the mysteries of Isis’.98 Lant observes that in London in 1801, the magician Paul de Philipsthal’s (d.1829) phantasmagoria was housed in the same venue as a show entitled ‘Aegyptiana’, a series of Egyptian scenes; that the poster for phantas-magoria expressly warned that patrons should not mistakenly attend the ‘Aegyptiana’ suggests ‘imaginary and physical alliances’ between the phantasmagoria and Egyptian subject matter in the minds of viewing publics.99 In America, meanwhile, audiences were thrilled by phantasmagoria produced from 1803 onwards; one performer by the name of William Bates showcased a ‘particularly intriguing image’ in 1804 of ‘An Egyptian Pigmy Idol, which instantaneously changes to a Human Skull’.100 Egyptian subject matter was, therefore, evident in phantasmagorical shows on both sides of the Atlantic from early in the nineteenth century.

Subsequently, the Victorian era saw an explosion in the use of the magic lantern in illusory contexts; its ‘popularity … as a visual storytelling device peaked in the middle to late nineteenth century’, with venues such as the Royal Polytechnic Institute hosting ‘displays that often involved up to six lanterns, and pioneered technology such as dissolving views that foreshadowed the cinematograph’s moving images’.101 The magic lantern and early cinema were, as Simone Natale outlines, part of a web of technologies that produced superimposed images that included spirit photography and stage-magic devices.102 While the magic lantern itself did not originate in the nineteenth century, it was refined and put to innovative purposes across this era, beginning with the phantasmagoria and culminating, in several historians’ accounts, in the special effects that we witness in some of the earliest moving pictures.103

Photographic lantern slides became available from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, a development that meant hand- painted and photographic slides could be used in combination to produce new and exciting results, theatrically accompanied by music and sound effects.104 Fantasy and reality collided at venues such as the Royal Polytechnic, where the traditional subject matter of magic- lantern shows depicting ‘popular fairy stories, cautionary tales, old jokes, ghostly apparitions, [were] all mixed up with recent reports of explorers’ exploits and the latest news’, giving the undertakings an exotic and sometimes archaeologically inflected twist, and suggesting the presence of the fantastic in the real world.105 The influence of such visual collages is suggested in Algernon Blackwood’s short story ‘A Descent into Egypt’ (1914). Blackwood’s narrator recounts the tale of the loss of his friend, who is drawn to the mysteries of Egypt and is ultimately consumed by them. The narrator is one of three men who all feel Egypt’s pull, and describes the effects that they experience as they come to be possessed by the spirit of Egypt:

In rapid series, like lantern- slides upon a screen, the ancient symbols flashed one after … and were gone … The successive signatures seemed almost superimposed as in a composite photograph, each appearing and vanished before recognition was even possible, while I interpreted the inner alchemy by means of outer tokens familiar to my senses.106

In ‘A Descent into Egypt’ the ‘ancient symbols’ of the past are visualised as ‘flash[ing]’, on the faces of the men, as if illuminated and projected onto these receptive forms by a magic lantern. The narrator is aware that something alchemical is taking place in their psyches, and that this is manifesting externally in their physical appearances, which reveal something Sphinx or Horus-like. As in earlier examples, this occult experience is meant to be real, although the language of optical illusion means that these ancient archaeological horrors are conceived of in relation to modern visualisation technologies. The use of simile reveals how Blackwood’s narrator’s grasp of the situation is shaky: he turns to the magic lantern and to the photograph as a means to express his experience and ultimately to comprehend it, but modernity is no match for the Egyptian supernatural. Blackwood’s narrator is evidently lucky to survive this experience.

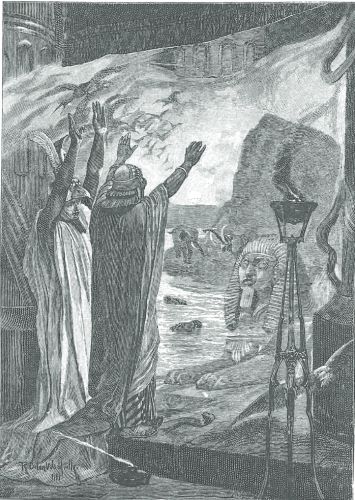

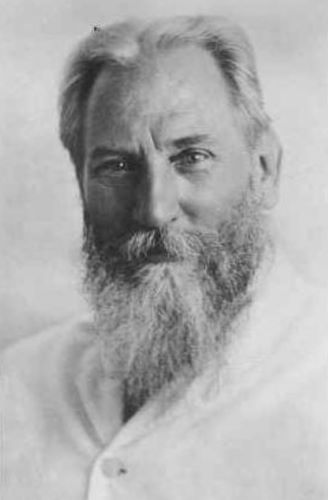

The introduction of fantastical and ghostly imagery into archaeological settings via projection technologies can be read in earlier texts too, notably in Haggard’s Cleopatra. Indeed, magic-lantern technology may well have been on Haggard’s mind at the time: a photographic portrait of Haggard from around the mid-1880s was made into magic-lantern slides by York & Son as part of a series entitled ‘Celebrities From Life’, likely around the time that Cleopatra was published.107 When Haggard’s protagonist, Harmachis, is first shown visions of the past by a priest of Isis, the pictures seem very similar to those produced by magic-lantern slides. Harmachis’s account of the experience, in which ‘the end of the chamber became luminous, and in that white light [he] beheld picture after picture’ emphasises the way in which the images are shown in quick succession and against a flat surface suitable for projection.108 Passages describing the individual images are separated by observations revealing the way in which each image gives way to the next: ‘the picture passed and another rose up in its place.’109 Here, Haggard de- emphasises the supernatural and makes the whole spiritual experience seem a surprisingly pragmatic affair. Nevertheless, it is significant that lantern slides were by no means devoid of atmosphere; their use in Masonic initiation ceremonies suggests that they maintained something of their mystical aura (Haggard was a Freemason), and here too Harmachis is initiated into the mysteries of Isis.110

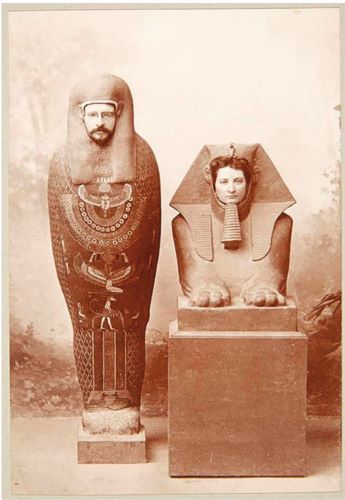

The scenes themselves have several features in common with contemporaneous slides showing images of Egypt. Harmachis mentions one in which he could see ‘the ancient Nile rolling through deserts to the sea’.111 Nile scenes were a common subject of hand-painted slides of Egyptian subjects, and photographic slides too once the technology became available. The accompanying illustration only serves to further the parallel between this scene and the projected image created by optical technologies (figure 1.5). The stream of light towards the image implies that the picture is being projected from behind the figures of Harmachis and the priest. The area of the scene taken up by the vision is also represented as existing within a defined rectangle, while the smoking lamp in the foreground perhaps alludes to the practice of projecting onto smoke, which was used to create a more ghostly effect, or else acted as a visual reminder of the light source required for such apparatus.

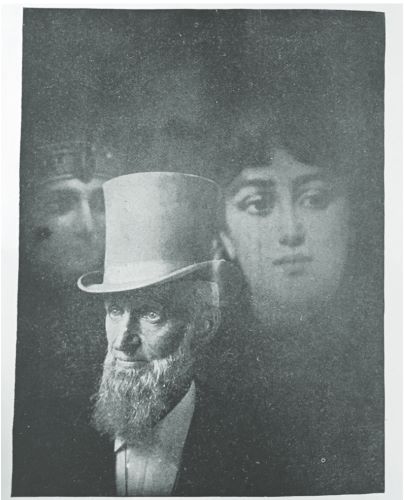

The image representing the appearance of the ghosts later in the novel (figure 1.6) also conforms to conventions of image projection. Again, the magic lantern appears to be referenced, both in the situation of a light source behind Cleopatra and Harmachis and, of course, in the subject matter of phantoms, which almost seem to materialise on a flat plane as if they were Pepper’s Ghosts.

The imagery of the phantasmagoria is further apparent in Cleopatra in the spirit of the dead pharaoh, Menkaura, which appears in the form of a ‘mighty bat’, ‘white in colour’, with ‘bony wings’ and ‘fiery eyes’.112 Bats, like phantoms, were popular in phantasmagorical displays, which tended to favour the established imagery of Gothic horror. The pale colouring of Haggard’s bat, and its ‘fiery eyes’ in particular, denote it as a being of light. A set of nineteenth-century magic-lantern slides in the Richard Balzer Collection creates the illusion of an animated bat flapping its wings, and Haggard’s bat’s repetitive movements – not just in flight but ‘rocking itself to and fro’ – suggest the simple but effective visuals that sets of mechanical magic- lantern slides could create.113 Witnessed in conjunction with the beautiful woman and the hideous corpse, and appearing and disappearing with supernatural speed, the bat reveals Haggard’s reliance on the tropes and practices of the phantasmagoria when creating his ancient Egyptian horrors.114 Indeed, the bat’s final appearance in the novel heralds the arrival of the crowd of spirits, as if one set of slides were giving way to another as part of a phantasmagorial display.

Beyond Haggard’s historical novel, the impact of magic- lantern technology on narratives of Egypt is palpable in a range of other genres, from children’s fiction to theosophical publications. The British politician James Henry Yoxall’s (1857– 1925) children’s adventure novel The Lonely Pyramid (1892) has, at its opening, a scene like an eccentrically coloured magic- lantern slide: ‘Yonder … are fair low rounded hills; at their feet a patch of emerald sward and feathery palms, a gleam of silver water; and amidst it all a loft, lonely Pyramid, of purple hue!’115 As John Plunkett observes, ‘[m] ore than any other genre, children’s books drew on optical recreations like the … magic lantern’, modest versions of this technology having become, by the late nineteenth century, available for domestic use and, as such, had entered the middle-class home to be enjoyed as a family activity.116 Intriguingly, for an illustrated book, however, these magic-lantern-esque views are not pictured, but left to the child reader’s imagination. A divide emerges between the rather more straightforward narrative illustrations and the more mystical optical effects conjured up in the mind’s eye and not permitted to appear materially on the page. Nonetheless, Yoxall’s textual depictions of these effects are evidently crafted to capture the young imagination and to suggest the spectacular. A reviewer for the Spectator’s literary supplement admired its ‘vividness and picturesqueness’, praising Yoxall’s ‘descriptions of pyramid interiors and desert scenery’.117

Our hero, Roy Lefeber, is in Egypt for the purposes of studying optics, specifically ‘the laws that govern the production of mirage’, and the descriptions of the Egyptian desert certainly linger on its unusual optical effects in spectacular terms:

The lovely landscape wavered, shifted, changed like the transformation scene at a theatre. A shaft of fuller light smote it like a sword; it shuddered, it shredded into filaments, it wavered … it rose, it rolled apart, it melted into rainbow- tinted haze, it disappeared.118

Yoxall’s listing and use of alliteration – ‘lovely landscape’, ‘it shuddered, it shredded’, ‘it rose, it rolled’ – provides a sense of rhythm to the descriptions of the constantly changing image, suggesting an almost trance- like captivation on Roy’s part. The theatrical simile further underlines the fascination commanded by these dramatic light effects. The child fears that the scene he witnesses is nothing more than a mirage – described in technological terms as ‘the magic-lantern of the desert’ – and indeed, when it disappears from view ‘like a silken, flashing curtain split and rolled asunder’ it is with the theatricality of seemingly instantaneous appearances and disappearances concealed and then revealed by curtains, common in stage magic.119 Once the protagonists arrive at the purple pyramid, Roy witnesses ‘a white and ghostly figure, gliding with silent foot’, and while this transpires not to be a revenant as they first suppose, is does mark the beginning of a litany of imagery that associates the pyramid with phantasmagorical horrors, from a statue of a crocodile so lifelike as to be presumed by the protagonist to be real – ‘the spirit of ancient Egypt … set to guard the mysteries of Isis’ – to the mummy of the female pharaoh Hatshepsut fixed in position, crouching before the goddess’s altar.120 As in Haggard’s text, the horrors of the Egyptian mysteries are best expressed in modern terms.121

Charles Leadbeater, a leading member of the Theosophical Society, also used the magic lantern to capture the phenomenology of the Egyptian occult. ‘The Forsaken Temple’, included in his collection of short narratives, The Perfume of Egypt and Other Weird Stories (1911), is one of several ‘true’ ‘stories’, among which are ‘personal experiences of [Leadbeater’s] own’.122 While he claims that ‘it may be difficult for one who has made no study of the subject to believe them, those who are familiar with the literature of the occult’, he assures, ‘will readily be able to parallel most of these experiences’.123 The tale begins with the relation of how the narrator was working as a music teacher for two young brothers and that, after their lessons were finished, as ‘these two boys were good physical mediums’, they would participate in séances.124 One evening, after the boys have left, the narrator wakes in the night to see one of the brothers in his bedroom, seemingly in a trance. The narrator then experiences ‘a change … in [his] surroundings’: ‘I found that we were in the centre of some vast, gloomy temple, such as those of ancient Egypt.’125 In this post- séance state, the narrator experiences a split consciousness, in which he is both looking at the boy, while he also ‘[sees]the wonderful paintings on the walls pass before [him] like the dissolving views of a magic lantern’.126 That he describes what he witnesses as an ‘exhibition’ furthers the simile comparing astral scenes of ancient Egypt to a modern visual display.

Henry Ridgely Evans, also referred to the phantasmagoria to describe his protagonist’s visual encounter with Egypt, in his The House of the Sphinx:

When night, with its blue- black canopy, studded with brilliant stars, has fallen upon the world of the Orient, these ancient ruins seem to breathe forth mystery … The silvery moon, sacred disk of Isis, floods the faces of the colossi, images of the gods, and intensifies their grotesque shadows. In this solemn hour of slumber and silence a weird phantasmagoria presents itself to our entranced vision. We behold the ruins restored, as if by magic; pylon and pillar, obelisk and avenue of sphinxes, are all intact, as of old.127

The moon provides the light needed to effect a near- magical transformation of the scene (the moon is not a light source, of course, but functions essentially as an enormous mirror, reflecting the light of the sun), and Evans invokes Isis to imbue this light with an occult association. As in his enchanting description of the Egyptian Hall, however, Evans knows that there is no genuine magic taking place, however, though it certainly appears ‘as if’ this is the case, and his presentation of this passage, just as his description of the Egyptian Hall, in the present tense, belies an effort to immerse his readership in lush descriptions that feel immediate. We (Evans uses the plural to include us along with his protagonist-narrator) are ‘entranced’ by the ‘weird phantasmagoria’ (the soft sibilance of Evans’s description maintains this dreamy quality), beguiled by some-thing that looks magical but which is, in fact, just a convincing optical effect. With the breaking dawn – like the theatrical rising of the house lights – the scene reverts back to the mundane (and the narrative reverts to the past tense).