By Dr. John Mullan

Lord Northcliffe Chair of Modern English Literature

University College London

Introduction

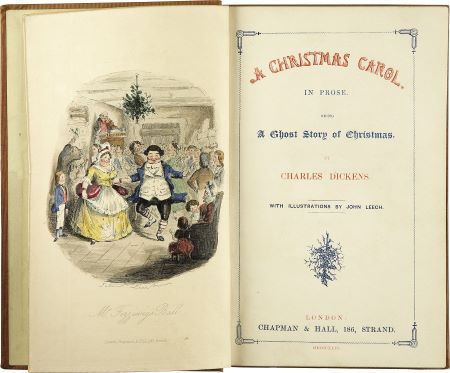

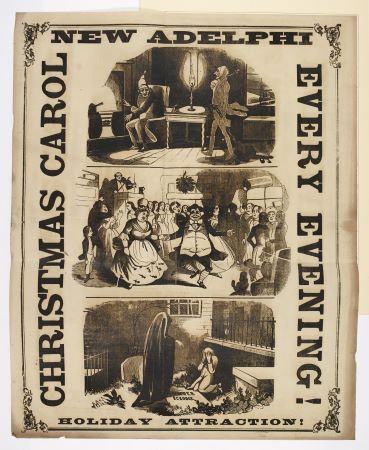

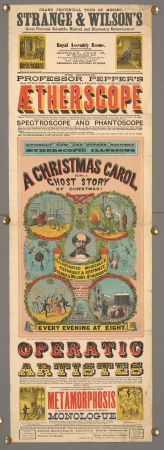

There had been ghosts in literature before the Victorians, but the ghost story as a distinct and popular genre was the invention of the Victorians. Charles Dickens was hugely influential in establishing the genre’s popularity – not only as a writer but also as an editor: his journals Household Words and All the Year Round specialised in ghost stories, and other contemporary journals followed. Dickens’s close friend and biographer John Forster said that the novelist had ‘a hankering after ghosts’. Not that Dickens exactly believed in ghosts – but he was intrigued by our belief in them. In A Christmas Carol (1843), the first of his ghost stories, he harnesses that belief by making the supernatural a natural extension of the real world of Scrooge and his victims. This is a long way from the spectres of earlier Gothic fiction.

The Terrible and the Comical

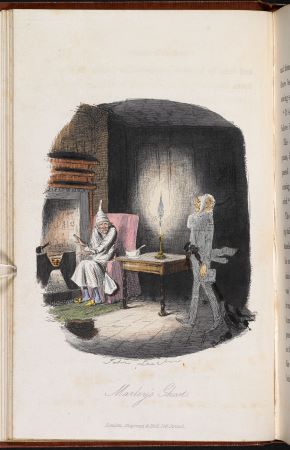

The first strictly supernatural sight in the story is the door knocker on the outside door of Scrooge’s chambers that metamorphoses, as the miser looks at it, into the face of his former partner, Jacob Marley, dead for seven years. ‘The hair curiously stirred, as if by breath or hot-air; and though the eyes were wide open, they were perfectly motionless’. Yet Dickens’s sense of fantasy brings the horrible and comic together: in the surrounding gloom, the face has ‘a dismal light about it, like a bad lobster in a dark cellar’. The weird mix of the terrible and the comic is kept up when Marley’s ghost finally appears carrying its chain of cash-boxes, keys, padlocks and the like. Like a parody ghost, its body is transparent, as Scrooge observes. ‘Scrooge had often heard it said that Marley had no bowels, but he had never believed it until now’ (Stave 1).

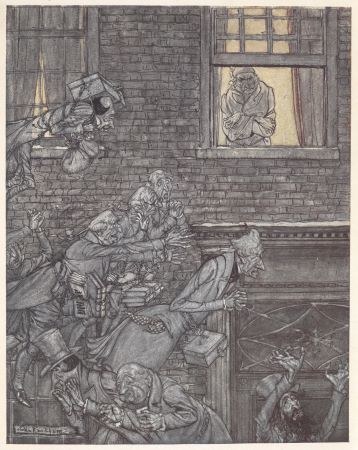

City of Spectres and Animated Objects

On Christmas Eve the city is itself a place of spectres where ‘it had not been light all day’. Outside Scrooge’s counting house, the fog is so dense ‘that although the court was of the narrowest, the houses opposite were mere phantoms’. The bell in a nearby church tower strikes the hours and quarters ‘as if its teeth were chattering in its frozen head up there’. After Marley’s Ghost has left him, Scrooge looks out of his window and sees ‘the air filled with phantoms’, many of them chained souls who had once been known to Scrooge (Stave 1). It is like a fantastic vision of the city that Scrooge already knows well. Like Macbeth, Scrooge, because of his sins, sees visions that are for him alone.

Allegory and Morality

The apparitions are inescapable. ‘Show me no more!’ Scrooge cries to the Ghost of Christmas Past. What he sees is a punishment to him. ‘But the relentless Ghost pinioned him in both his arms, and forced him to observe what happened next’ (Stave 2). The phantom as literary device enables Dickens to explore the social and moral issues central to his fiction: – poverty, miserliness, guilt, redemption.

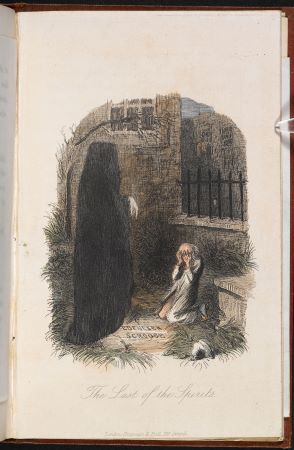

The ghosts borrow in their appearance from a tradition of allegory. There is the strange child/old man that is Christmas Past, clutching a branch of holly yet trimmed with summer flowers. There is the large and avuncular Ghost of Christmas Present, tinged more and more with age as his visions draw to their close. And there is ‘The Phantom’ that is the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, shrouded and ‘stately’ and mysterious. Their shapes tell you about author’s moral design.

Structure and Time-Consciousness

The ghosts give the story its irresistibly logical structure, and make Scrooge think that he is prepared for each succeeding visitation. Preparing to meet the second of the three spirits, ‘nothing between a baby and a rhinoceros would have astonished him very much’ (Stave 3). But of course he is surprised. The Ghost of Christmas Present surprises him by showing him flashes of humour and happiness in the most unlikely of circumstances. And when Scrooge sees the visions revealed by the third of the spirits, he naturally fails to recognise what the reader knows from the first: that the dead man, abandoned after the scavengers have done with him, is himself.

Marley’s Ghost announces them. ‘You will be haunted … by Three Spirits’ (Stave 1). Scrooge is even told at what times they will appear. The ghosts bring fatality to the narrative: Scrooge cannot resist the visions they set before him. He must awake at the destined times to encounter the world that he has made for himself. Time-consciousness is built into the narrative (those bells). The ghosts have only their allotted spans. ‘My time is nearly gone,’ says Marley’s Ghost. ‘My time grows short,’ observes the first of the three spirits, ‘quick!’ (Stave 1; Stave 2). Chronology is of the essence: Christmas is a special day made all the more significant by the unfolding of these visions at their hours. On Christmas Eve Marley’s Ghost tells Scrooge of three visits in three consecutive nights, but he wakes to find that it is Christmas Day. ‘The Spirits have done it all in one night’ – which means that he still has the day to redeem himself (Stave 5).

A Christmas Carol is a brilliant narrative success, and was a huge commercial coup. It forged the association between Christmas and ghost stories, and led Dickens to write a series of such tales for Christmas. It also showed how the genre worked best within limitations of time and length, so that the short story and the novella were best suited to ghostly tales. Dickens had set a new literary fashion in motion.

Originally published by the British Library, 05.15.2014, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.