History’s record suggests that vigilance must not be the task of regulators alone, but of societies willing to question the sheen of health when it arrives packaged as fashion.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: When Health Becomes Fashion

The history of medicine is not a steady ascent toward enlightenment but a winding path marked by bursts of discovery and long shadows of error. Among the most telling illustrations of this uneven progress are the recurring waves of health fads that have swept through societies since the rise of modern consumer culture. These fads, often launched with the sheen of scientific endorsement and amplified by advertising, promised vitality, beauty, and relief from suffering. Yet many delivered the opposite: suffering, debilitation, and death. To examine these episodes is to study not merely the hazards of flawed science, but the deep entanglement of commerce, culture, and the human yearning for quick remedies.

Radium Water: The Glow of Death

In the early decades of the twentieth century, radium was a scientific marvel, its luminescent glow a visible sign of mysterious energies believed to confer health. Entrepreneurs, sensing both novelty and profit, bottled “radium water” as a tonic for vitality. Wealthy patrons paid dearly for the promise of renewed vigor, convinced that ingesting the same element thrilling physicists in the laboratory would reanimate their bodies.1 It was not until gruesome cases of necrosis and radiation poisoning, most infamously the slow, public death of industrialist Eben Byers, that the fad collapsed.2 Byers, once an exemplar of high society, became a cautionary figure, his disfigured body a silent testimony against the marketing of lethal substances.

Cocaine Tonics: The Stimulant of Civilized Nerves

If radium water was the fad of the elite, cocaine tonics were the stimulant of the aspiring classes. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, cocaine was widely available in patent medicines, sold in formulations promising to sharpen wit, banish fatigue, and restore flagging spirits.3 Even respected physicians prescribed it for depression and morphine addiction. The allure was amplified by endorsements from figures like Sigmund Freud, who extolled its virtues before its addictive potential and destructive neurological effects were fully recognized.4 By the 1910s, medical journals began sounding alarms about psychosis and physical collapse, but the cultural momentum had been strong enough to sustain the market until legal restrictions intervened.

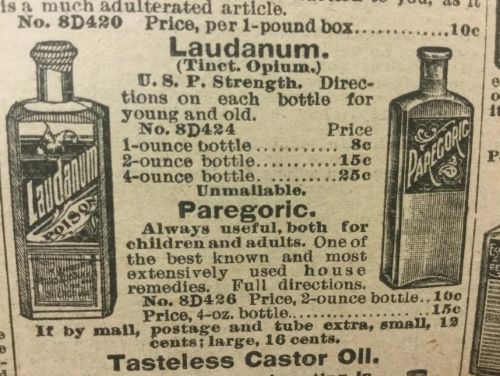

Heroin Cough Syrup: The Soothing Poison

Where cocaine had promised stimulation, heroin—ironically synthesized as a supposedly safer alternative to morphine—offered calm. Introduced by Bayer in 1898, it was marketed as a cough suppressant for both adults and children.5 Ads depicted cherubic infants sleeping peacefully, their mothers assured of a remedy that was “non-addictive” and “harmless.” The claims collapsed under the weight of mounting evidence: children developing dependencies, adults suffering from respiratory depression, and patients falling into cycles of addiction.6 By the 1920s, most Western nations had moved to regulate or ban heroin entirely, but not before a generation had learned the peril of trusting pharmacological reassurances.

Tobacco as Health Product: The Smoke of Deception

The twentieth century’s longest-running medical fraud may have been the marketing of tobacco as a health aid. Early cigarette advertisements boasted endorsements from physicians, dentists, and even opera singers, claiming that certain brands soothed throats, aided digestion, or maintained “healthy nerves”.7 In a cultural climate that associated smoking with sophistication, these medicalized claims found ready audiences. The turning point came slowly: epidemiological studies in the 1950s linked smoking to lung cancer with increasing statistical certainty, yet decades of industry obfuscation delayed public acceptance.8 The persistence of the myth highlights not only the profit motive but the power of cultural identity to resist scientific correction.

Thalidomide: The Tragedy of Modern Trust

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, thalidomide emerged as a pharmaceutical marketed for its ability to ease morning sickness in pregnant women. Hailed as safe and non-addictive, it was prescribed widely in Europe and parts of the developing world.9 The reality was catastrophic: thousands of infants were born with severe limb deformities, internal organ damage, or blindness. While some physicians had voiced early concerns about its safety, the absence of rigorous pre-market testing allowed the disaster to unfold on a massive scale.10 The tragedy not only devastated families but also reshaped global drug regulation, creating stricter protocols for safety trials and post-market surveillance.

Fen-Phen: The Diet Pill Collapse

In the 1990s, the combination of fenfluramine and phentermine—known as Fen-Phen—promised rapid weight loss for millions seeking a medical shortcut to thinness.11 Initially approved for short-term use, the drug combination was prescribed far beyond those limits, often to otherwise healthy individuals. Reports of heart valve damage and pulmonary hypertension began to emerge, culminating in a massive recall and billions of dollars in legal settlements.12 Fen-Phen’s rise and fall encapsulated the recurring pattern of modern fads: scientific novelty translated into consumer excitement, followed by a delayed reckoning when evidence could no longer be ignored.

Conclusion: Cycles of Faith and Disillusion

These six fads, spanning nearly a century, differ in their substances and specific harms, yet they share a structural similarity: the harnessing of scientific prestige to market a promise, the cultural readiness to believe, and the slow, uneven process of disillusionment. Each case reveals that the public appetite for miraculous cures, whether glowing, intoxicating, soothing, or slimming, remains as potent as the forces that eventually expose their dangers. History’s record suggests that vigilance must not be the task of regulators alone, but of societies willing to question the sheen of health when it arrives packaged as fashion.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Luis A. Campos, Radium and the Secret of Life (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 114.

- Jay Speakman, “The Shocking Story of Eben Byers: How Radium Poisoning Destroyed Him,” MIRA Safety (April 25, 2025): https://www.mirasafety.com/blogs/news/the-shocking-story-of-eben-byers?srsltid=AfmBOooDTR4vnOc11SbMRaymzuP4TcMWS_wifpLgSuE-MLFOhrJsyNrb.

- Joseph Spillane, Cocaine: From Medical Marvel to Modern Menace in the United States, 1884–1920 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000), 23–26.

- Sigmund Freud, “Über Coca,” Centralblatt für die gesammte Therapie 2 (1884): 289–314.

- Walter Sneader, “The Discovery of Heroin,” The Lancet 352:9141 (November 21, 1998): 1697-1699.

- David T. Courtwright, Dark Paradise: A History of Opiate Addiction in America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001), 115–118.

- Allan M. Brandt, The Cigarette Century (New York: Basic Books, 2007), 61–64.

- Richard Doll and A. Bradford Hill, “Smoking and Carcinoma of the Lung,” BMJ 2 (1950): 739–748.

- James H. Kim and Anthony R. Scialli, “Thalidomide: The Tragedy of Birth Defects and the Effective Treatment of Disease,” Toxicological Sciences 122:1 (July 2011): 1-6.

- L. Stern, “The Lesson of Thalidomide,” Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 14:4 (July-August 1973): 660-661.

- Sidney M. Wolfe, “Fen-Phen and the FDA,” Public Citizen Health Letter (June 9, 1997).

- H.M. Connolly et al., “Risk of Valvular Heart Disease Associated with Fenfluramine-Phentermine,” New England Journal of Medicine 337, no. 9 (1997): 581–588.

Bibliography

- Brandt, Allan M. The Cigarette Century. New York: Basic Books, 2007.

- Campos, Luis A. Radium and the Secret of Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

- Connolly, H.M., et al. “Risk of Valvular Heart Disease Associated with Fenfluramine-Phentermine.” New England Journal of Medicine 337, no. 9 (1997): 581–588.

- Courtwright, David T. Dark Paradise: A History of Opiate Addiction in America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Doll, Richard, and A. Bradford Hill. “Smoking and Carcinoma of the Lung.” BMJ 2 (1950): 739–748.

- Freud, Sigmund. “Über Coca.” Centralblatt für die gesammte Therapie 2 (1884): 289–314.

- Kim, James H. and Anthony R. Scialli. “Thalidomide: The Tragedy of Birth Defects and the Effective Treatment of Disease.” Toxicological Sciences 122:1 (July 2011).

- Sneader, Walter. “The Discovery of Heroin.” The Lancet 352:9141 (November 21, 1998).

- Speakman, Jay. The Shocking Story of Eben Byers: How Radium Poisoning Destroyed Him.” MIRA Safety (April 25, 2025). https://www.mirasafety.com/blogs/news/the-shocking-story-of-eben-byers?srsltid=AfmBOooDTR4vnOc11SbMRaymzuP4TcMWS_wifpLgSuE-MLFOhrJsyNrb

- Spillane, Joseph. Cocaine: From Medical Marvel to Modern Menace in the United States, 1884–1920. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.

- Stern, L. “The Lesson of Thalidomide.” Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 14:4 (July-August 1973).

- Wolfe, Sidney M. “Fen-Phen and the FDA.” Public Citizen Health Letter, October 1997.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.14.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.