The 1980s were not the beginning of Christian nationalism, but they were its decisive breakthrough. From the seeds of cultural anxiety in the 1970s, evangelicals organized into a political bloc.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: A Nation at the Crossroads of Faith and Politics

The 1980s occupy a singular place in the history of American religion and politics. It was in this decade that Christian nationalism (the belief that the United States is, or ought to be, a nation defined by Christian values and institutions) moved from the margins of evangelical subculture into the mainstream of political life. Though its roots stretched back to earlier eras, the 1980s marked a decisive consolidation of Christian nationalist activism. Evangelical leaders, organizations, and voters established themselves as a formidable bloc within American conservatism, reshaping national debates over morality, law, and identity.

Christian nationalism did not appear ex nihilo. It was the product of social upheavals in the 1960s and 1970s, sharpened by judicial rulings, civil rights conflicts, and cultural transformations. But it was the political marriage with Ronald Reagan’s Republican Party in the 1980s that gave it unprecedented scope. The era reveals how theological convictions, cultural anxieties, and partisan politics intertwined to produce a movement that continues to reverberate into the twenty-first century.

Seeds in the 1970s: From Cultural Anxiety to Political Mobilization

The rise of Christian nationalism in the 1980s can only be understood against the backdrop of the preceding decade. The Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade (1973) legalized abortion nationwide, provoking outrage among conservative evangelicals and Catholics alike.1 At the same time, federal efforts to strip tax-exempt status from racially segregated Christian academies, such as Bob Jones University, struck at the heart of evangelical institutional life.2 Many conservative Christians came to see the federal government not as a neutral arbiter but as a hostile force seeking to dismantle their way of life.

Jimmy Carter’s election in 1976 briefly seemed to signal an alignment of evangelical conviction and political leadership. Carter openly described himself as “born again,” making evangelical identity more visible than ever. Yet Carter’s policies disappointed conservative Christians. His support for civil rights, feminism, and pluralism revealed the gap between evangelical religiosity and evangelical politics. By the late 1970s, leaders like Jerry Falwell were calling evangelicals into organized political action.

The formation of the Moral Majority in 1979 marked the crystallization of this mobilization. Falwell and allies such as Paul Weyrich sought to unite evangelicals, fundamentalists, and conservative Catholics into a national political force. Their message blended patriotism, biblical authority, and traditional family values into a program of Christian nationalism that promised to restore America to its supposed moral foundations.3

The Reagan Alliance and the 1980 Election

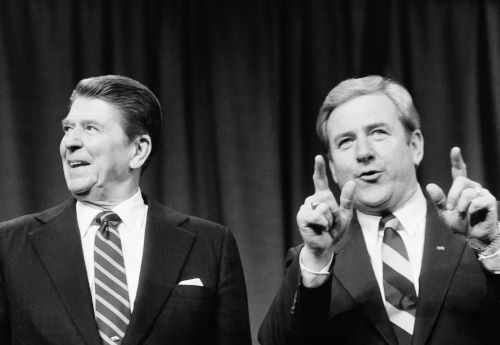

Ronald Reagan’s victory in 1980 symbolized the political arrival of Christian nationalism. Though Reagan himself was not a particularly devout churchgoer, he understood the symbolic power of evangelical language. He famously declared in a 1980 campaign speech, “I know you can’t endorse me, but I endorse you,” to rapturous applause from evangelical leaders.4

Reagan’s rhetoric fused religion and nationalism. He spoke of America as a “shining city on a hill,” invoking Puritan imagery of divine chosenness. His administration courted evangelical leaders, aligning with their priorities on abortion, school prayer, and opposition to gay rights. For Christian nationalists, Reagan represented both validation and opportunity: validation that their faith mattered in public life, and opportunity to shape national policy.

The 1980s therefore marked not only the rise of a movement but also its institutional embedding within the Republican Party. Evangelical voters became a reliable constituency, reshaping electoral politics for decades to come.

Televangelism and the Media Revolution

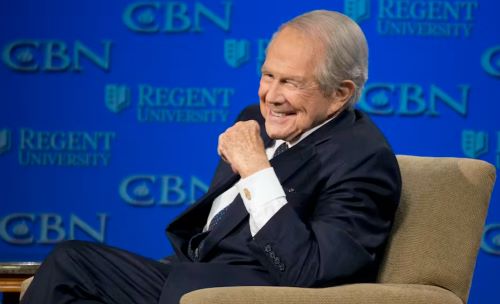

The 1980s were also the golden age of televangelism, which played a crucial role in spreading Christian nationalist ideology. Satellite television allowed preachers to reach millions of households, blending revivalism with political messaging. Pat Robertson’s 700 Club, Jerry Falwell’s broadcasts, and James Robison’s sermons presented viewers with a narrative that fused biblical prophecy, American patriotism, and cultural conservatism.

Televangelism created a new public sphere for Christian nationalism. Viewers were not only encouraged to pray and donate but also to vote, lobby, and resist secular culture. Religious broadcasting amplified anxieties about abortion, pornography, homosexuality, and secular education, framing these as threats not merely to morality but to the very survival of the nation.

Yet televangelism also carried risks. Scandals involving Jim Bakker and Jimmy Swaggart in the late 1980s damaged the credibility of evangelical media. Still, the infrastructure of Christian television had already cemented a powerful link between evangelical faith and conservative politics, providing Christian nationalism with a constant megaphone.

Family Values and the Politics of Morality

Christian nationalism in the 1980s revolved around the defense of “family values.” This phrase served as shorthand for opposition to abortion, feminism, divorce, and homosexuality, as well as support for school prayer and traditional gender roles. Leaders framed these issues as not merely moral but civilizational: America’s future as a Christian nation depended on defending the family.

The political potency of this framing lay in its dual appeal. For evangelicals, it was theological, rooted in biblical conceptions of order. For secular conservatives, it resonated as a defense of tradition against cultural upheaval. The rhetoric of family values thus allowed Christian nationalism to forge alliances across the conservative spectrum, integrating religion more deeply into the political right.

Fracture and Transformation at the Decade’s End

By the late 1980s, Christian nationalism faced both challenges and transformations. The dissolution of the Moral Majority in 1989 reflected organizational fatigue and public backlash. Televangelist scandals tarnished the image of evangelical leaders. Yet these setbacks did not signal decline so much as evolution.

Pat Robertson’s 1988 presidential campaign, though unsuccessful, demonstrated that evangelical networks could mount serious national campaigns. The creation of the Christian Coalition in 1989 carried the energy of Christian nationalism into the 1990s, shifting its strategy from national lobbying to grassroots organization. The infrastructure built in the 1980s (churches mobilized as political bases, voters habituated to religious appeals, and leaders skilled in media) ensured that Christian nationalism would remain a durable force.

Conclusion: The Legacy of the 1980s

The 1980s were not the beginning of Christian nationalism, but they were its decisive breakthrough. From the seeds of cultural anxiety in the 1970s, evangelicals organized into a political bloc that reshaped American conservatism. With Ronald Reagan as their champion, televangelism as their medium, and “family values” as their rallying cry, Christian nationalists embedded themselves into the structures of national politics.

The contradictions of the movement (its reliance on leaders often undone by scandal, its tension between theological conviction and political pragmatism) were evident from the start. Yet the decade cemented its identity as a movement that equated America’s destiny with Christian faith. The legacies of the 1980s remain visible today in the continued power of religious nationalism to define debates over identity, morality, and the very meaning of the American republic.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Daniel K. Williams, God’s Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 153–156.

- Randall Balmer, Thy Kingdom Come: How the Religious Right Distorts the Faith and Threatens America (New York: Basic Books, 2006), 16–20.

- Frances FitzGerald, The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017), 451–456.

- Darren Dochuk, From Bible Belt to Sunbelt: Plain-Folk Religion, Grassroots Politics, and the Rise of Evangelical Conservatism (New York: W. W. Norton, 2011), 393–397.

Bibliography

- Balmer, Randall. Thy Kingdom Come: How the Religious Right Distorts the Faith and Threatens America. New York: Basic Books, 2006.

- Dochuk, Darren. From Bible Belt to Sunbelt: Plain-Folk Religion, Grassroots Politics, and the Rise of Evangelical Conservatism. New York: W. W. Norton, 2011.

- FitzGerald, Frances. The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017.

- Williams, Daniel K. God’s Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Originally published by Brewminate, 09.05.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.