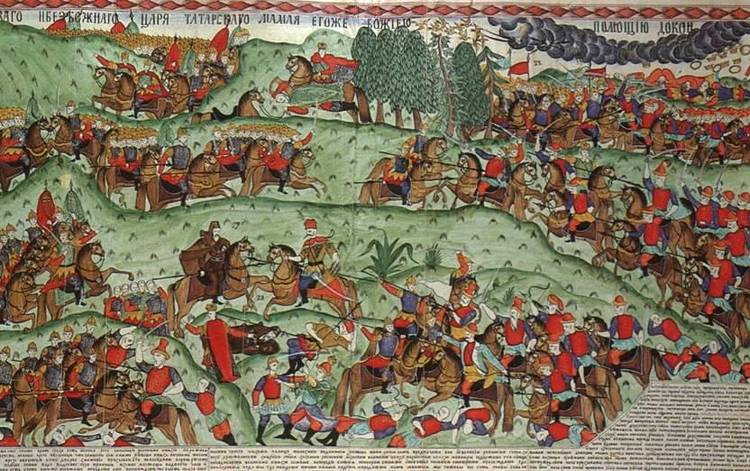

The Golden Horde extended from the Caucasus to Hungary to Constantinople, inspiring fear across the known the world.

By Michael Goodyear

J.D. Candidate

University of Michigan Law School

Introduction

The Golden Horde was the European appanage of the Mongol Empire (1206-1368 CE). Begun in earnest by Batu Khan in 1227 CE, the territory that would eventually become the Golden Horde came to encompass parts of Central Asia, much of Russia, and other parts of Eastern Europe. Later converting to Islam, the Golden Horde would meld aspects of cultures from Europe, Asia, and the Middle East while ruling Russia for over two centuries. At its height, Mongol raids from the Golden Horde extended from the Caucasus to Hungary to Constantinople, inspiring fear across the known the world of the fearsome Mongol horsemen, or, as they knew them, the Tartars.

They Came from the East

Under the leadership of Genghis Khan (r. 1206-1227 CE), the Mongol Empire began the greatest military machine of the medieval world. Expanding from Korea to the Caspian Sea under Genghis’ reign, his sons and grandsons would bring the Mongol Empire to its heights, creating the largest contiguous land empire the world has ever seen.

According to Mongol tradition, Genghis divided his empire into appanages for each of his four sons. Genghis’ first son, Jochi received the lands furthest from Mongolia, those around the Ural Mountains and beyond. It was to fall to Jochi’s son, Batu Khan (r. 1227-1255 CE), to consolidate these future conquests and establish what would become known as the Golden Horde.

Ogedei Khan (r. 1229-1241 CE), Genghis’ son and Batu’s uncle, ordered a massive Mongol campaign east across the Ural Mountains to conquer Europe. In 1236 CE, the Mongol horde descended into the Volga River valley. Nothing to stand against Mongol warfare as the Volga Bulgars fell in 1237 CE, followed by the major Russian cities of Vladimir-Suzdal, Kiev, and Halych between 1238 and 1240 CE. Only the city of Novgorod, far to the north, escaped the Mongol onslaught.

With Russia vanquished, the Mongol horde marched west. A three-prong attack led by Batu and the famous Mongol general Subotai devastated the Polish and Teutonic Knights at the Battle of Legnica in 1241 CE before the main army crushed the Hungarian army at the Battle of Mohi (aka the Battle of the Sajo River) later that year. Europe lay bare before the seemingly invincible Mongol horde, but the death of Ogedei back in Mongolia made the Mongols retreat and allowed Europe to breathe a sigh of relief. These first raids lead the Europeans to dub the Mongols Tartars, both from the name of a Mongol clan, the Tatars, and the fact that they seemingly came from the depths of hell, or Tartarus.

The Mongols would never venture as far as the Adriatic again, but the Golden Horde would remain a significant presence in Europe for the next two centuries. By playing the role of kingmaker following the death of Guyuk Khan in 1248 CE, Batu established the permanence of his family’s rule over the Golden Horde portion of the Mongol Empire. Batu set up a capital at Sarai near the Volga and introduced a pattern of tribute from the Russian princes that would become a hallmark of the Golden Horde. In fact, one of the potential origins of the name “Golden Horde” is that the color derived from that of Batu’s splendid golden tent. However, the color gold was associated with Genghis’ family (called the “golden” family) and it was associated with the center in the Mongol’s color system for cardinal directions, so those could also be potential origins.

Looking to the South

Batu’s brother Berke (r. 1257-1266 CE) continued the precedent of Batu’s robust leadership. He led campaigns into Poland, Lithuania, and Prussia, reinforcing the European fear of the Mongols. But perhaps the most important event of Berke’s reign was his conversion to Islam.

The fact that Berke was a Muslim put him at odds with Hulegu Khan (r. 1256-1265), the leader of the Ilkhanate, which had conquered Iran and Iraq and had become one of the four main powers in the Mongol Empire. Hulegu had sacked the great Muslim city of Baghdad in 1258 CE and had killed the last Abbasid caliph by rolling him in a carpet and trampling him to death. The Golden Horde and the Ilkhanate also bordered each other in the Caucasus, which became a flashpoint. In 1262 CE, war broke out between the two nominal parts of the Mongol Empire. Berke formed an alliance with Baybars (r. 1260-1277 CE), the Mamluk Sultan in Egypt. An Ilkhanate invasion of the Golden Horde ended in defeat when the Golden Horde general Nogai led a surprise attack at the Battle of Terek in 1262 CE. At the same time as this Berke-Hulegu War, there was a civil war back in Mongolia over who would become Great Khan.

The Mongol Empire, although it would nominally remain united, was in reality shattered. In the coming decades, the Chaghataids would claim the rest of Transoxiana from the Golden Horde and Berke would die during a march against the Ilkhanate. Later in the 13th century CE, the Golden Horde would become involved in the conflict between Kublai Khan (r. 1260-1294 CE) and the Ogedeid leader Kaidu, supporting the latter. Internecine conflict with the Ilkhanate would continue as well.

Meanwhile, the Golden Horde became involved in the Balkans when a former Seljuk sultan was held captive by the Byzantine Empire. Nogai, with the help of the Golden Horde vassal Bulgaria, invaded the Byzantine Empire in 1271 CE and forced the emperor, Michael VIII Palaiologos (r. 1259-1281 CE) to marry one of his daughters to Nogai. The khan Mengu-Timur (r. 1266-1280 CE) opened the Golden Horde to trade, giving the Genoese and Venice trading colonies at Azov and Caffa, and ordering the Russians to allow German traders into their lands.

After Mengu-Timur’s death, Nogai was the de facto ruler of the Golden Horde. He raided Europe from Lithuania to Bulgaria and forced Serbia to accept vassalage. While Nogai was a powerful warrior leader, his death in 1299 CE did not overly halt the campaigns of the Golden Horde.

The Triumph of Islam

The Golden Horde experienced many changes in the 14th century CE. For one, Islam came to stay. While Berke had been the first Mongol prince to convert to Islam, other rulers of the Golden Horde, including Toqta, continued to follow Tengrism (Mongol pagan beliefs) or Buddhism. That changed when Uzbeg (r. 1313-1341 CE) proclaimed Islam as the official religion of the Golden Horde. In this vein, Uzbeg continued to strengthen relations with the Mamluks of Egypt, even marrying a Mongol princess to the Egyptian sultan.

Instead of active military campaigns, Uzbeg and his successors kept the Russian princes subservient and divided by playing them against each other. Tver was the leading city backed by the Mongols, but when the city’s population slaughtered their Mongol residents in 1327 CE, Uzbeg switched his support to the city of Moscow.

Under Uzbeg, the Golden Horde remained active. Toqta (r. 1291-1312 CE) married an illegitimate Byzantine princess, strengthening the Golden Horde-Byzantine alliance that had existed since the time of Nogai. Yet under Uzbeg, the Mongols, in alliance with their Bulgarian vassal, raided the Byzantine Empire for two decades. They also propped up an independent Wallachia against Hungary. Meanwhile, Uzbeg opened up the Crimea to trading posts by the Genoese and Venetians. The 1340s CE featured the last Mongol campaigns into Poland.

Uzbeg remained active against the Ilkhanate, invading on several occasions. When the Ilkhanate collapsed in 1335 CE, some Ilkhan nobles turned to Uzbeg to assume the throne, but he declined. Meanwhile, the Golden Horde capital of Sarai grew as Muslim culture’s demand for mosques and bathhouses dictated expanded urban life. At perhaps the height of the Golden Horde’s power, Janibeg (r. 1342-1357 CE) accepted the vassalage of the Polish king Casimir III the Great (r. 1333-1370 CE), the Chaghataid Khanate, and the Jalayirids of Iraq, as well as conquering the former Ilkhanate city of Tabriz.

The 14th-Century CE Decline

Yet the success of Uzbeg and Janibeg quickly unraveled. The Black Death had taken a serious economic toll on the Golden Horde. From 1359 to 1382 CE, the Golden Horde was wracked by civil war. During this time the Mongol grip on Eastern Europe also began to slacken. In fact, the Mongols faced their first serious defeats in Europe during this time. Lithuania defeated the Mongols at the Battle of Blue Waters in 1362 CE, following up the battle by conquering Kiev. The Russian principalities scored their first victory over the Mongols in 1380 CE at the Battle of Kulikovo, which is considered a turning point in Russian history.

Revival under Tokhtamysh

The decline of the Golden Horde was briefly arrested by Tokhtamysh, a protegee of Tamerlane (r. 1380-1395 CE). Tokhtamysh besieged Moscow in 1382 CE and, ignoring a promise to not attack the city, slaughtered the inhabitants when the city opened its gates. The next year Tokhtamysh avenged the loss at the Battle of Blue Waters by defeating the Lithuanians at the Battle of Poltava. Both the Russians and Lithuanians were back under the Mongol yoke and forced to pay tribute.

But Tokhtamysh’s successes made him overreach himself. He next decided to turn on his mentor Tamerlane. Tamerlane’s vengeful campaign sacked Sarai, burned the Golden Horde’s land, destroyed its army, and forced Tokhtamysh to flee. Tokhtamysh fled to Lithuania and later tried and failed to retake the Golden Horde. Meanwhile, Tamerlane had so devastated the trade routes in the Golden Horde that the state would never recover economically.

Russia Resurgent

After Tamerlane’s destruction and the civil wars that followed, the Golden Horde was increasingly limited to the lower banks of the Volga River. The Golden Horde broke up into several separate khanates: the Khanate of Khazan, the Khanate of Astrakhan, the Khanate of the Crimea, the Khanate of Sibir, the Nogai Horde, and the Kazakh Khanate. The last major khan of the Golden Horde, Ahmed (r. 1465-1481 CE), led a campaign against Lithuania and Moldavia that ended in defeat.

Perhaps more importantly for history, Ahmed also led the Mongols during the Battle of the Ugra River in 1480 CE. Ivan III of Moscow soundly defeated the forces of the Golden Horde and the battle has ever since been recognized as the end of the Mongol domination of Russia.

A Long Afterglow

When the Golden Horde ended is an answerless question. Even a decade after the Battle of the Ugra River, a Golden Horde raid struck Poland. The broken-off khanates of Russia continued to survive for decades more, and in the case of the Crimean Khanate, even centuries. Most of the Golden Horde’s successors were victims of Ivan the Terrible (r. 1547-1584 CE). Khazan fell in 1552 CE, Astrakhan in 1556 CE, and Sibir in 1582 CE. Perhaps the true successor of the Golden Horde was the Crimean Khanate, which sacked Sarai in 1502 CE. Yet the Crimea was a vassal of the Ottoman Empire from 1475 CE onwards. The Crimean Khanate survived until it was annexed by Russia in 1783 CE.

Regardless of when the Golden Horde officially ended, its centuries-long existence left an undeniable mark on Russia and on the history of Eastern Europe. At the crossroads of Central Asia, Europe, and the Middle East, the Golden Horde influenced events from Poland and the Byzantine Empire to Egypt and Central Asia. As the Tartars, the Mongols of the Golden Horde played a key role in the story of the Mongol Empire and in that empire’s legacy in Europe and popular imagination.

Bibliography

- Chambers, J. The Devil’s Horsemen. (Castle, 2003).

- Halperin, C. Russia and the Golden Horde. (Indiana University Press, 1987).

- Jackson, P. The Mongols and the West. (Routledge, 2018).

- Jackson, P. (transl.). The Mission of Friar William of Rubrucköngke, 1253-1255. (Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2009).

- Juvaini, A. Genghis Khan. (Univ of Washington Pr, 1997).

- Kahn, P. Secret History of the Mongols. (Cheng & Tsui, 2005).

- Ronay, G. The Tartar Khan’s Englishman. (Cassell, 1978).

- Rossabi, M. The Mongols and Global History. (W. W. Norton & Company, 2010).

- Saunders, J. J. The History of the Mongol Conquests. (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001).

Originally published by the Ancient History Encyclopedia, 10.14.2019, under a Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.