By Dr. R Gnanasekaran

Assistant Professor, Department of English

Karpagam University

Abstract

In view of the fact that grammar is a central phase of instructing a language, many techniques have been adopted to instruct it effectively over the time. Right from the evolution of grammar till today, instructing grammar has undergone a number of changes. In recent times, some language researchers have turned to some alternatives to traditional grammar teaching. Instead of focusing on grammatical forms, now the syllabus framers are giving more prominence to form and meaning relationship. Acquiring grammatical structures alone without monitoring their capacity does not help the students to build up their open capability in speaking a language. If someone wants to communicate clearly, the necessity of ‘Performance’ rather than ‘Competence’ is must. This article begins with the development of grammar in Greece and proceeds onward portraying the part of it in the Renaissance age.

The Evolution of English Grammar

English sentence structure or grammar has been extraordinarily impacted by the Greek and Latin models. The impact of Latin on English is profound and wide. The English sentence structure has experienced many changes to get the shape that it is having now. A moment investigation of the foundation of the English linguistic use empowers us to look how our English grammar has been developed over the span of time.

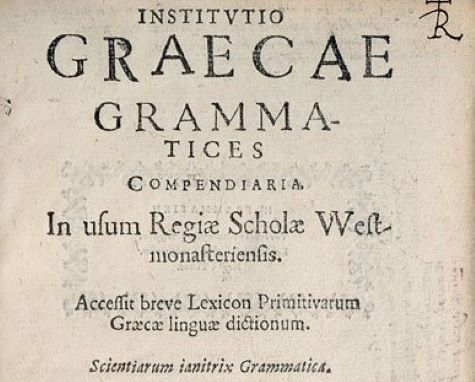

The Grammar which is connected to the Greek and Latin representation is called traditional grammar. The school teachers are likely to teach this traditional grammar to their pupil as a sign of their curriculum. In those days, this traditional grammar was concerned with the learning of the syntactic rules, sentence constructions, paradigms of verb tenses, and noun cases in languages such were recognized with particular regard to exceptions. We need to analyze some grammatical concepts and terminologies first, so that we could trace the traditions of the grammatical descriptions and methodologies in Europe from the old to the modern.

Panini’s Sanskrit grammar and Sibaway’s Arabic grammar became the models for the traditional representation of the Sanskrit grammar in India and Arabic in Islamic lands respectively. The Techni grammatike (science of grammar) usually attributed to Dionysius Thrax (ca.100 BC), supplemented by the distinctively syntactic writings of Apollonius Dysoclus (ca. 200 AD) similarly formed the basis of the didactic and descriptive grammar of different languages and language in common in the traditional grammar school of Europe, at least up to the end of the nineteenth century. This traditional grammar survived for a long time in many places. Even much of its terminologies are found in twentieth century theoretical linguistics, but these terms have come to be used in slightly different ways.

Grammar and Its Origin

The grammatical study gets started in the ancient Greece. In Greece the necessity of grammar sprang two sources. On the one hand there was a general philosophical interest in language in general and its relation with other Greek languages at the day. On the other hand Macedonia won over Asia Minor and Egypt in third century BC. It imposed the Greek language and literature on its subject peoples, for anyone who inspired to have a general standard of education. It is from this derivation alone the usage ‘Hellenistic age’ has become into the existence. Even the roman successors to the Macedonians continued the same policy giving much importance to Greek language and literature. This Hellenization of Asia Minor and Egypt required teachers and text books at all levels. Greek was taken as a major educational activity and classical literature became its theme.

The philosophical analysis of grammar rightly started with Plato’s division of sentence into two parts like onama, ‘name’ (subject) and rhema (predicate). This persisted through Aristotle’s various statements about grammar in which he made an explicit distinction between words and sentences, each as semantic units in their specific ways. It’s just like the generative grammarians’ initial rule – ‘S- NP+ VP’. At this stage the primary division distinguished not so much classes of words as sentence components. It got translated into Latin as ‘parts of orationis’. Oratio was used to mean both ‘sentence’ as here and spoken discourse which gave birth to the term which is still there in modern times for word classes as parts of speech this Greek division of sentence lays the foundation of all subsequent European grammatical description.

Another generation of philosophers emerged who emphasized prepositional logic. Instead of devoting their attention to the Aristotelian logic of class membership and class inclusion, they concentrated on linguistic topics like phonetics, semantics, syntax etc. Finally the Alexandrian grammarians around 100 BC introduced a set of word classes. Which are categorized as noun, participle, article, pronoun, preposition, adverb and conjunction which continued throughout Greek antiquity and Middle Ages. In this arrangement participle was given its independent status because partook of both case and tense inflexion, as it did it in Latin, thus sharing the criteria to define both nouns and verbs. This classification lasted for a long time.

Romans did not have hesitation to follow ‘conquered Greek teachers’ in almost all intellectual fields notwithstanding the fact that they were the rulers. Latin grammar also took over the Greek model in morphology and syntax by making some minor changes.

Grammar in the Middle Ages

The Middle Ages simply witnessed the continuation of antiquity under the changed condition. The perceptible changes in this period were fall of the Western Roman Empire because of the Germanic invasions while the Eastern, largely speaking held itself in being as Rome’s legitimate successor until the final Turkish conquest of Constantinople in 1453. Secondly before the collapse of Rome as a secular capital, Christianity had already been accepted as the state religion of the empire as a whole political entity, with all its consequences in education, scholarship, literature and the arts in general.

Both Latin and Greek lost the importance respectively in the East and West. Latin was used in the east only by a small number of scholars and diplomats while Greek study greatly declined until around the fourth century, but the short didactic works of Donatus and voluminous institutions grammar of Priscian (ca. 500), contributed much to the traditional grammatical presentation of Latin in the west. These books summarized the accepted version of morphology and syntax which had been worked out for Greece. Priscian owes his gratitude to Appollonius as the greatest authority on grammar.

Latin grammar started serving two purposes. It was a basic component of higher education because it was regarded as one of the seven ‘liberal arts’ along with didactic, rhetoric, magic, arithmetic, geometry and astronomy and Latin was the language of church, law, official communication and of all sorts and the only means of communication of the Western world. Therefore knowing Latin was very important for any education and any higher position in life. However from the eleventh century on, especially in the University of Paris, a powerful development, philosophical grammar came to the force. This development was largely supplemented by the Western scholars of Aristotelian philosophical texts and the church view point expressed by St Thomas Aquinas. They claimed that there was nothing repugnant between Aristotolianism and Christian belief. They also demanded the explanatory appropriateness in grammatical theory over and above descriptive adequacy of the Latin teacher. This was to be realized by explaining Priscian’s grammar through reference to its logical and metaphysical foundation and justification. Inspite of some criticism, Priscian’s grammar remained as the same but it was found that his grammar depends upon the dominant Aristotolianism of the middle ages. A contemporary of Priscian wrote that Priscian had described the language well enough but had failed to explicate the principles of grammar itself. The philosophical grammarians openly criticized the mere school teachers of the language as an inferior class of scholars.

However Priscian’s Graceo – Roman system of grammar remained the database and the taxonomy of Latin language. Though in the course of time some changes occurred they could not replace Donatus and Priscian. Both philosophical and didactic grammar supplemented the presentation of Donatus and Priscian rather than replacing them. The philosophical grammarians (modistae) formalized the relation of hinted at by Appollonius and set forth with examples in a versified teaching manual, the Doctrinale by Alexander of villedieu in the twelfth century. With this came a clearer understanding of the prepositional function of linking a noun, pronoun or noun phrase to a verb and of different clauses required in the government and the semantic relations involved. And syntax as opposed to the logical distinction between subject and predicate was explicitly set out. This innovative philosophical grammar did not pay any attention to the established orientation of the Priscianic tradition but it didn’t have its own way everywhere.

During the Renaissance and After

With the advent of renaissance, the grammarians encountered some new problems. These problems arise because of the vast expansion of European acquaintance with extra-European languages often as with Chinese on the one hand and American–Indian language on the other hand, displaying grammatical structures unlike anything known or conceived by Europeans and second following the rise of nationalism and a strong commercial middle class and in vernacular languages of Europe came to be seen as requiring and deserving grammatical teaching in their own rights. There was a requirement for teaching correct English, French and a Standard English in speech community. But grammar retains its old tradition in most of the parts. Latin grammar stood as the model for all the people. With the evolution of the Latin through Romans, the arrival of the Old English has become an obvious one.

References

- Abbot G. Towards a more Rigorous Error Analysis. International Review of Applied Linguistics, 1980. Print.

- Close, R.A. English as a Foreign Language. George Allen & Unwin: Print, 1974.

- Halliday MAK, Language structure and language function. In J. Lyons (Ed.), New Horizons in Linguistics,

Harmondsworth: Penguine. Print. 1970; 140-65. - Quirk, et.al. A Grammar of Contemporary English, Longman: London, Print, 1972.

- Richards JC, Plott J, Platt H. Dictionary of Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics. Longman, London,

Print.1996. - Widdowson HG. Teaching Language as Communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Print, 1978.

Originally published by the International Journal of English Research 3:1 (January 2017, 57-48), ISSN:2455-2186, free and open access, republished for educational, non-commercial purposes.