By Dr. Vasile-Ovidiu Prejmerean

Researcher

The Institute for Archaeology and Art History Cluj-Napoca

The Romanian Academy

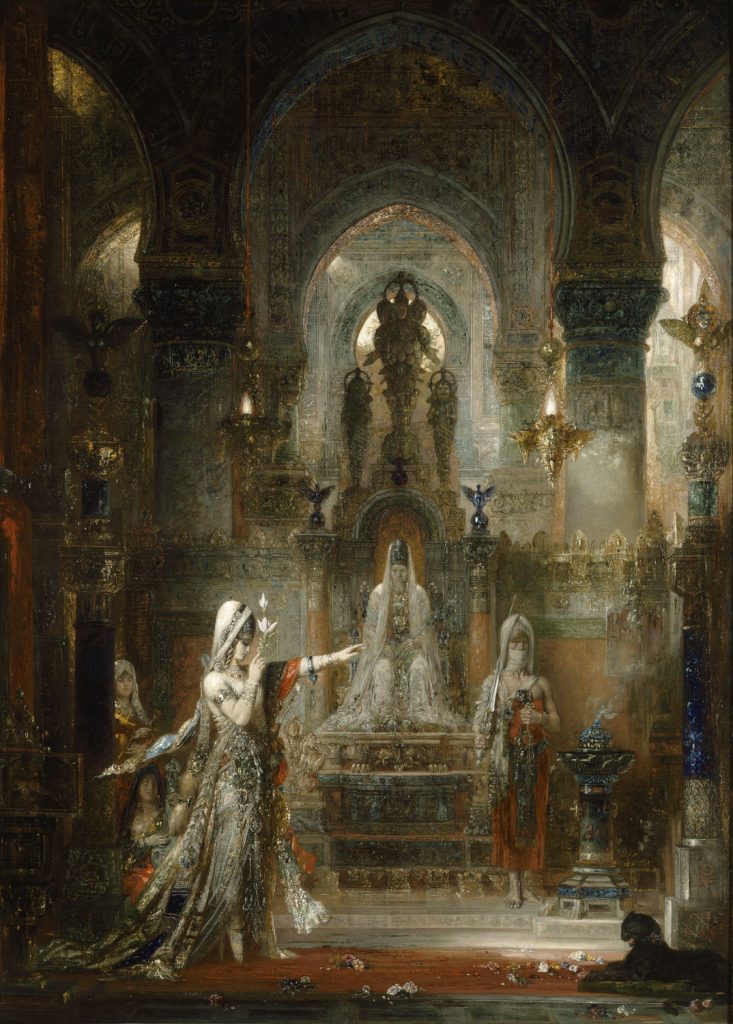

Salome dancing before Herod, with its bewildering subject matter and lush colors, is without a doubt one of the most remarkable paintings of the nineteenth century.

The painting was first exhibited at the 1876 Salon (and shortly thereafter at the 1878 World’s Fair), along with The Apparition, Hercules and the Lernaean Hydra and Saint Sebastian Baptized a Martyr — all works by the French symbolist and history painter Gustave Moreau. The Salon was an annual public art exhibition in Paris, organized by the prestigious Academy of Painting and Sculpture. Generally history paintings depicted narratives from the Bible or stories from the classical past in dynamic compositions, conveying didactic messages to the viewer.

Alongside these other paintings, Salome shows not only Moreau’s preference for religious, literary, and mythological subjects, but also his desire to picture the struggle between “spirit” and “matter”—a subject Moreau pursued his entire career.

The theme of Salome is one that Moreau returned to time and again. The artist explored the subject in more than one hundred sketches and drawings as well as in numerous paintings—ranging from highly elaborate to sketchily rendered—and even in sculpture (both Salome and The Apparition figured in Moreau’s waxworks). Moreau was not alone in his passion for the theme of Salome, as other famous artists — Lucas Cranach, Caravaggio, Titian, Guido Reni, Artemisia Gentileschi, Aubrey Beardsley, and Nabil Kanso, to name just a few — shared this interest. Salome is the woman whose dance led to the demise of John the Baptist, a Jewish itinerant preacher and one of the most significant figures in the New Testament, also known as the Forerunner of Christ in Christianity and the prophet John in Islam.

In the New Testament, both Matthew (14:1-11) and Mark (6:14-29) tell of the famous banquet story in which Herodias, having grown angry at John the Baptist for saying she could not marry her ex-husband’s brother, asks her daughter to request John’s head from her half-uncle as payment for her dance. Although neither of these sources mention Salome by name, we can learn of her from Flavius Josephus’ Jewish Antiquities of the year 93-94 (Book XVIII, Chapter 5, 4).

Given the scarcity of texts, and the fact that Salome seems not to know what to ask her uncle for until instructed by her mother, it is unclear if Salome is truly the evil temptress she is supposed to embody, or just an unwitting instrument in her mother’s hands.

Salome’s complex and ambiguous story offered vast artistic freedom[1]. It is no wonder that Moreau refers to her as “My Salome.”[2] In his writings, Moreau underlines the sacredness of the scene, but also warns of the proverbial power of the femme fatale (a seductive woman who lures men into dangerous situations—a popular subject among Symbolist artists) as one who can be fatal to any man—even saints.[3] Moreau’s contemporaneous viewers also focused on Salome as “femme fatale” (perhaps most famously, the Symbolist novelist and art critic J. K. Huysmans in his novel À rebours).

This skewed interpretation shaped painters’ imagination for generations. Moreau makes clear that his goal in turning to Salome as subject, was to reinvigorate high art through beauty and idealism[4]. Of course, not every painter had the same lofty goals, as Henri Regnault’s version makes plain, given its orientalist depiction and lush representation of Salome and her surroundings. Regnault’s 1870 Salome played an important role in Moreau’s decision to tackle the subject, as he wanted to show the world a different rendering of the subject, rooted not in orientalism and the straightforward depiction of a femme fatale, but in mystery, eclecticism, and the “archeology of sentiment and imagination,” which he attributed to Rembrandt.[5]

Given the interest Moreau paid to the Dutch master’s subjects and technique during the 1870s, it is no wonder that much of Remdrandt’s treatment of light and darkness as well as his rich colors find new life in Moreau’s painting.

As scholars Peter Cooke and Julius Kaplan pointed out, Moreau had multiple sources from which he could have drawn inspiration, such as Rembrandt’s Christ Driving the Money Changers from the Temple and Ingres’ Antiochus and Stratonice for the architectural structuring of the painting’s composition; Jacques Louis David’s The Oath of the Horatii for Salome’s uncharacteristically theatrical gesture of her left hand; Giovanni Bellini’s San Zaccaria Altarpiece for the character’s self-absorbed pose; and Delacroix’s Jewish Wedding in Morocco, where we encounter a dance pose similar to that of Moreau’s Salome. Anti-theatricality constituted a constant in Moreau’s oeuvre as he preferred immobile, somnolent figures to vividly animated ones.

If we look closely, we notice that Salome doesn’t really dance[6]; instead, she appears to hover, as though she belonged to a magical realm. The dissonance between her “inward” gaze and the unnatural position of her arms further enhances this perception, as does the lotus flower she holds upright. Its symbolism is ambiguous. Does it signal lust, or is it a symbol of purity? Moreau’s typically enigmatic approach made him a target for the promoters of Naturalism, most notably Émile Zola, who accused him of retreating into his dreams and offering an artistic response to the challenge posed by science—one that couldn’t possibly have value in the modern age. Such criticism hurt him deeply and only fueled Moreau’s purposeful cultivation of ambiguity. Naturalism refers here to a late nineteenth-century literary movement that rejected Romanticism and embraced realism, objectivity, and social commentary.

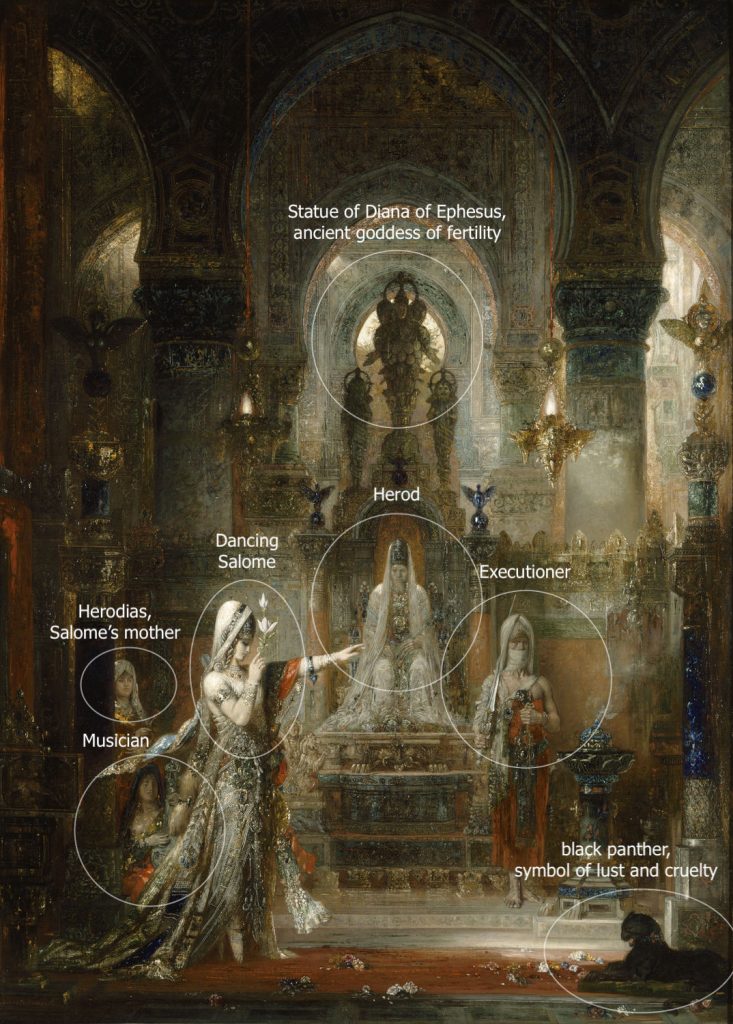

As viewers, we are aligned to mirror Herod as he sits, seemingly transfixed, his passivity underlined by the majestic statue of Diana of Ephesus—an ancient goddess of fertility —that towers above him. It is not only Herod who mirrors the voyeuristic role of the viewer; the musician on the left, Herodias behind him, glance towards Salome’s face or her upraised left arm. Only the executioner looks elsewhere.

The black panther in the foreground, a symbol of lust and cruelty, looks down forward and implicitly submits to the otherworldly will of the dancing Salome. If Salome the woman dazzles the viewer through her beauty and pose, Moreau’s depiction of Salome does so not only through the glittering colors, but also through the marvelous abundance of detail, that scatter our gaze and prompts us to admire the. wealth of carefully crafted minutia we are offered. Some critics, contemporaneous with Moreau, like Georges Lafenestre, were enchanted and baffled by the sheer abundance of details in his paintings.

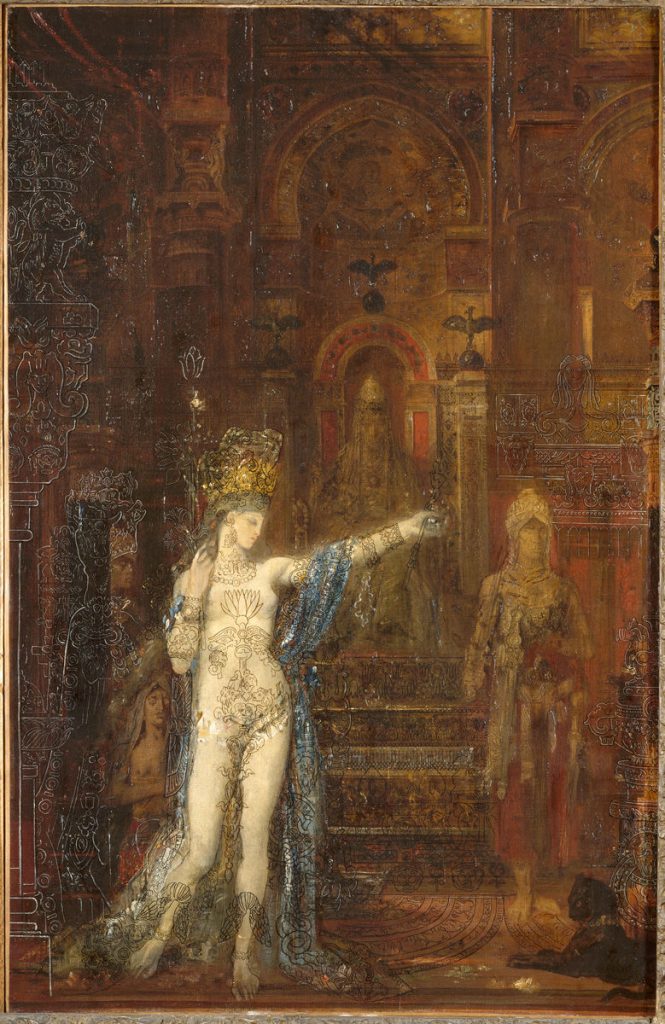

Another version of the subject further illustrating Moreau’s love for detail and complexity is the so-called Tattooed Salome.

The viewer here is left wondering whether we are to understand the markings as imprinted on Salome or if they instead form part of a decorative pattern on the canvas that are more apparent against the light tones of her body.

On each side of the lotus “tattoo,” there are two giant eyes staring at the viewer. These “tattooed” eyes, complete with a pair of eyebrow decorations, reveal a mirroring face, whilst Salome’s “real” eyes are lowered. The “tattooed” gaze catch the viewer’s and block him or her, as it were, from exploring the woman’s body, acting as an additional layer of protection against our voyeurism. Further down, we see a “tattooed” Gorgon-like creature, with her tongue sticking out, and reptilian figures undulating around Salome’s inner thighs.

Matter and spirit appear woven together in another image by Moreau, known as Salome Entering the Banquet Hall, in which the temptress raises the platter with Saint John’s head towards the dove symbolizing the Holy Spirit. In this drawing, Salome holds the platter with the saint’s head close to the level of her own, while she peers intently into his eyes. Above them both, but clearly closer to Saint John, the Holy Spirit reigns supreme, while the executioner exists the scene, blade on his shoulder. Another painting by Moreau, Apparition, marks another confrontation of sorts between Salome and the head of Saint John.

Moreau’s long standing interest in the story of Salome and its many interpretations is made apparent through the artist’s varied approaches to the theme and in his desire to transcend to the symbolism Salome traditionally enacts—as a warning against temptation. Instead, Moreau looks to Salome as link between matter and spirit. So intertwined are Moreau’s artistic agenda and Salome’s symbolic content that one could credibly assert that even as Moreau created images of Salome, Salome shaped him.

Endnotes

- Salome was taken up as a theme numerous times in literature as in the visual arts. If we are to consider the 19th century only, Heine’s Atta Troll, Flaubert’s Three Stories (the third, Hérodias, possibly influenced by Moreau’s painting), Massenet’s Hérodiade and Wilde’s Salome come to mind. Furthermore, it is quite possible that Moreau was acquainted with Flaubert’s 1862 Salammbô and with Mallarmé’s 1864 Hérodiade, which would have influenced his approach. See Julius Kaplan’s “Salome” subchapter in Gustave Moreau. Theory, Style and Content (Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI, 1982).

- “Thus, in my Salomé, I wanted to depict a figure of a sibyl and religious enchantress having a mysterious character. So then I designed the costume that is like a reliquary.” See Écrits sur l’art par Gustave Moreau. Textes établis, présentés et annotés par Peter Cooke. A Fontfroide, Bibliothèque artistique et littéraire, MMII, p. 99. See also Peter Cooke, Gustave Moreau: History Painting, Spirituality and Symbolism (Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2014), pp. 81-93.

- [3]“This woman who represents the eternal woman, flimsy bird, often fatal, walking through life with a flower in hand, in search of her vague ideal, often terrible, and always walking, trampling everything under her feet, even geniuses and saints. This dance is executed, this mysterious walk takes place before the death who looks at her incessantly, gaping and attentive, and before the executioner whose sword strikes… A saint, a decapitated head are at the end of her path which will be strewn with flowers. Everything happens in a sanctuary that elevates the spirit towards the gravity and the idea of higher things.” See Écrits, pp. 97-8.

- When speaking of another of his artworks, Jupiter and Europa, Moreau makes his goal clear: “I want, when I address materialist and anti-spiritual youth without respect for art or religion, I want, I’d say, to bring them through the spectacle of the eyes to comprehend the beautiful, which will make them understand the good.” See Écrits, p.79 and Scott C. Allan, “Gustave Moreau and the Afterlife of French History Painting”, PhD thesis, Princeton, pp. 48-54.

- Écrits, p. 344. His eclecticism became proverbial as he used a vast variety of sources — Egyptian, Indian, Roman, Etruscan, Persian, Chinese, Moorish, Turkish, etc. — for the costumes and the architectural settings in his paintings.

- See Peter Cooke, “It isn’t a Dance: Gustave Moreau’s ‘Salome’ and ‘The Apparition’” in Dance Research, vol. 29, no. 2 (winter 2011).

Originally published by Smarthistory, 08.23.2020, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.